A Sensorimotor Psychotherapy Perspective*

NONVERBAL EXCHANGES ARE the heartbeat of all relationships. Ethologists point out the significance of animal behaviors that communicate an invitation for a particular activity, such as to play, to be sexual, or to fight. Infant researchers highlight the body-based communications between infants and attachment figures that generate affect regulation capacities, procedural memory, and so much more. Similarly, implicit dialogues experienced and enacted alongside the verbal dialogue during the therapy hour are receiving increased attention as an essential element of therapeutic change. Therapeutic action is seen as extending far beyond that of understanding and interpreting patients and their behavior to participating in and attending to what is being enacted beyond the words, visibly reflected in gesture, posture, prosody, facial expressions, eye gaze, and so forth.

Body-based affective models take into account the dominance of the nonverbal “implicit self” over the verbal “explicit self” (Schore, 2009, 2010, 2011; Schore & Schore, 2007). The unconscious implicit self can be conceptualized as not only having to do with conflicts and emotional pain but also with positive or adaptive retures. The unconscious itself is now thought to serve “much broader adaptive functions” than “primarily a defensive and repressive function” (Cortina & Liotti, 2007, p. 211).

The implicit self takes shape during the rapid, moment-by-moment nonverbal interactions between infants and parents. In a secure attachment, infants learn to repeat the actions that catalyze the desired response from their attachment figures, and they become increasingly effective at nonverbally signaling, engaging, and responding to others (Brazelton, 1989; Schore, 1994; Siegel, 1999; Stern, 1985, Tronick, 2007). Tronick (2007, 2011) has pointed out that movement and posture clearly denote the meaning infants make of interactions with attachment figures. One of his films shows an infant pulling his mother’s hair, eliciting a fleeting expressing of anger from her. The infant responds by lifting his arms in front of his face in a gesture that appears protective, apparently interpreting the mother’s angry expression as threatening. The mother’s anger is momentary, and she swiftly seeks to repair the rupture in their connection, making every effort to reengage and play with her infant. Eventually he lowers his arms, relaxes his body, and smiles. On the contrary, in insecure attachments, the infant may be left in prolonged dysregulated states with little or no interactive repair, or may be frightened, abused, and/or neglected by attachment figures, leading to disorganized attachment (Lyons-Ruth, Bronfman, & Parsons, 1999). In these cases, affect regulatory mechanisms fail to develop optimally, social engagement and nonverbal signaling and proximity-seeking behaviors are compromised, and the infant’s nonverbal cues may be unclear or contradictory.

Although the “somatic narrative” is usually beyond the grasp of the conscious mind, it continuously anticipates the future and powerfully determines behavior. This chapter emphasizes the centrality of implicit processes in human behavior, and the significance of nonverbal behavior in the therapy hour. Body-based embedded mindfulness interventions that directly treat the visible physical indicators of the implicit self within the interpersonal context of the therapeutic dyad are illustrated as a way to alter the somatic narrative and change the implicit self.

Implicit Relational Knowing

Through both positive and negative affect-laden interactions with parents, the child acquires “implicit relational knowing”—that is, “how to do things with others” (Lyons-Ruth, 1998). Devoid of verbal descriptions or conscious understanding, implicit relational knowing powerfully informs us how to “be” in relationship; what vocalizations, expressions, or actions will be welcomed or rejected by others; and what to expect in relationships. Lyons-Ruth points out that although implicit relational knowing is procedural, it is markedly different from what is commonly thought of as procedural knowledge (e.g., driving a car). The procedurally learned actions related to this knowing are accompanied by conscious or unconscious emotions and perceptions that are rooted in the past. They have a quality of being on autopilot—we no longer have to think about what we’re doing, as when we drive the car or type these words—or when our posture, facial expressions, and gestures automatically change as we interact with our attachment figures.

Although words are unavailable to describe early or forgotten formative interactions with attachment figures, the somatic narrative tells the story of implicit relational knowing and implicit predictions. When “Suzi’s” therapist complimented her on her new outfit, Suzi’s spine slumped, her head lowered, her shoulders curled forward, and she scooted backward in her chair. However, Suzi was unaware of these action sequences that reflected the appraisal of her implicit self, and she was mystified as to why she suddenly felt fearful when the moment before she had felt fine. Studies show that people with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) tend to respond to compliments negatively (Frewen, Neufeld, Stevent, & Lanius, 2010), and Suzi’s reaction seemed to reflect the shame she felt (but could not speak of and was not aware of) and the trauma she had experienced at the hands of her father as she began to grow into an attractive young woman.

Bromberg states, “When self-continuity seems threatened, the mind [and body] adaptationally extends its reach beyond the moment by turning the future into a version of past danger” (2006, p. 5). Suzi unconsciously associated compliments with abuse, turning future interactions with her therapist into perilous ones characterized by shame for what had happened in the past and fear for what she implicitly forecasted would happen in the future with her therapist. Action sequences like Suzi’s convey implicit predictions, expectations, intentions, attitudes, emotions, and meanings to others.

Implicit Knowing of the Self

Our sense of self is determined both by the story we tell ourselves verbally and by the story we tell ourselves nonverbally through our affect regulation capacities and other reflexive automatic behavior such as body posture and movement. A variety of studies demonstrate the impact of posture and other physical actions upon experience and self-perception. Subjects who received good news in slumped posture reported feeling less proud of themselves than subjects who received the same news in an upright posture (Stepper & Strack, 1993). Schnall and Laird (2003) showed that subjects who practiced postures and facial expressions associated with sadness, happiness, or anger were more likely to recall past events that contained a similar emotional valence as that of the one they had rehearsed, even though they were no longer practicing the posture. Similarly, Dijkstra, Kaschak, and Zwaann (2006) demonstrated that when subjects embodied a particular posture, they were likely to recall memories and emotions in which that posture had been operational. Suzi’s slumped posture conveyed implicit meaning to her about herself. It seemed to diminish her self-esteem and contribute to, if not induce, feelings of shame, helplessness, and fear associated with the past. The patient’s behavior is alive in the present with action sequences associated with the past, even in the context of a “safe” therapeutic alliance. Clearly, the implicit self is threatened by that which would challenge the perceived safety of familiar patterns of both relational knowing and self-knowing. The meanings of past experiences might show themselves in the constriction or collapse of the body as they did with Suzi, the shaking of a dysregulated nervous system, tension in the larynx and tightness in the voice reflecting a loss of social engagement, or in the avoidance of or locking in of eye contact. It is clear from such nonverbal behaviors that the implicit selves of our patients predict that the future will repeat the shame and peril that went before, no matter how strongly their explicit selves refute this position and describe the future as different from the past.

Functions of Nonverbal Behavior

Characteristic gestures, habitual postures, and action sequences reflect and sustain long-standing meanings and predictions. They reveal persistent emotional biases (e.g., a forward-thrusting chest and tension in the upper body may contribute to chronic anger, whereas a sunken chest and downward turning head contribute to sadness or grief) and beliefs (e.g., overall tension, quick, focused movements, and erect posture all support working hard and may indicate a belief such as, “I have to be a high achiever to be loved”). Nonverbal behaviors serve many functions in addition to anticipating the future, including affect regulation, emotional expression and communication, and signaling a readiness for or aversion of particular activities or interactions. These behaviors may be enduring action sequences, such as perpetually hunched shoulders, or fleeting expressions and gestures, such as a momentary narrowing of the eyes.

Nonverbal behaviors regulate the here-and-now exchange between people: The intonation of the voice or a thoughtful look away might indicate that the speaker has more to say; tensing the body and lifting the chin might impart a “stay away” message; whereas lowering the head and bending the body slightly forward might signal compliance or submission. Verbal points can be strengthened or emphasized by physical cues, such as the deep sigh and downturned head of a patient describing depression. Nonverbal behaviors might tone down a verbal message or make it more palatable, such as the disarming smile and forward leaning of a patient when she told me how angry she was at me.

These implicit somatic communications may be designed to elicit a particular response from the therapist. One patient responded by narrowing his eyes, tightening his chest, frowning slightly, and looking away when I asked about a relationship he did not want to discuss, effectively conveying his wish that I would drop the subject. Verbal and nonverbal messages might contradict each other as well, and can seek to hide aspects of internal experience as well as make them known. One patient may say she feels fine as her shoulders roll inward and a furrow appears on her brow, whereas another smiles as he speaks of his grief. We often see the signs of dissociative parts of the self in conflicting simultaneous or sequential nonverbal indicators, as when a patient reached out to shake my hand as he leaned his upper body away from me.

Nonverbal communications can be intentional or unintentional, conscious or unconscious, clear or confusing. These cues may represent a unified implicit self or contradictions among dissociative parts of the self. The unconscious, unintentional, and involuntary cues are of most interest to psychotherapists because they tend to indicate that which is under the surface, beyond the words, visibly revealing elements of behavior that reflect and sustain the implicit self or selves. The dance that ensues within the relationship, including the therapist’s unconscious responses (by his or her own implicit self) to the expressions of the patient’s implicit self, is the essence of therapy.

Bromberg states that the “road to the patient’s unconscious is always created nonlinearly by the [therapist’s] own unconscious participation in its construction while he is consciously engaged in one way or another with a different part of the patient’s self” (2006, p. 43). Alongside the verbal narrative, unconscious encoding and decoding are taking place in a meaningful nonverbal conversation between the implicit selves of therapist and patient. Encoding “involves an ability to emit accurate nonverbal messages about one’s needs, feelings, and thoughts,” and decoding “involves an ability to detect, accurately perceive, understand and respond appropriately to another person’s nonverbal expressions of needs, interactions, feelings, thoughts, social roles” (Schachner, Shaver, & Mikulincer, 2005, p. 148). The ongoing interactive process of encoding and decoding shapes what happens within the relationship without conscious thought or intent. Note that the implicit selves of both patient and therapist are engaged in this dance.

Nonverbal Indicators in Treatment

Kurtz states that psychotherapists ought to be on the lookout for nonverbal cues he calls “indicators,” which are “a piece of behavior or an element of style or anything that suggests . . . a connection to character, early memories, or particular [unconscious] emotions,” especially those that reflect and sustain predictions that are “protective, over-generalized and outmoded” (2010, p. 110). Therefore, not every nonverbal cue is an indicator. For example, reaching for a cup of tea or brushing one’s hair out of the eyes is not usually an indicator. Indicators are those nonverbal behaviors that help the therapist (implicitly and explicitly) “draw hypotheses about the client: what kind of implicit beliefs are being expressed and what kind of early life situations might have called for such patterns and beliefs” (p. 127).

Indicators encompass both the affect-laden cues reminiscent of early attachment interactions that shape the movements, postures, gestures, prosody, and facial expressions of the child, as well those that reflect dysregulated arousal and animal defenses elicited in the face of trauma. The therapist intends to bring the experience of these indicators into the present moment of the therapy hour. Therapy must “activate those deep subcortical recesses of our subconscious mind where affect resides, trauma has been stored, and preverbal, implicit attachment templates have been laid down” (Lapides, 2010, p. 9). Activating these elements requires right-brain to right-brain affective resonance and interaction rather than analytical, cognitive, or interpretive approaches (cf. Schore, 1994, 2003, 2009, 2012).

Indicators that register consciously for therapist or patient can be explored explicitly, along with the associated affect, even while the content they represent remains unconscious. Grigsby and Stevens suggested that recognizing indicators and disrupting automatic behaviors hold more promise than conversing about what initially happened to shape them: “Talking about old events . . . or discussing ideas and information with a patient . . . may at best be indirect means of perturbing those behaviors in which people routinely engage” (2000, p. 361). It may not be enough to gain insight without changing procedural action sequences. There are essentially two ways that implicit procedural learning can be addressed in therapy: “The first is . . . to observe, rather than interpret, what takes place, and repeatedly call attention to it. This in itself tends to disrupt the automaticity with which procedural learning ordinarily is expressed. The second therapeutic tactic is to engage in activities that directly disrupt what has been procedurally learned” (p. 325).

Listening to the somatic narrative along with the verbal narrative naturally stimulates curiosity and awareness of nonverbal indicators. Therapist and client together interrupt the automaticity of these indicators when they become mindful of them, “not as disease or something to be rid of, but in an effort to help the patient become conscious of how experience is managed and how the capacity for experience can be expanded” (Kurtz, 1990, p. 111). Note that the general notion of mindful attention as being receptive to whatever elements emerge in the mind’s eye is different from mindful attention directed specifically toward nonverbal indicators. Instead of allowing patients’ attention to drift randomly toward whatever emotions, memories, thoughts, or physical actions might emerge, therapists use “directed mindfulness” to guide the patient’s awareness toward particular indicators that provide a jumping-off point for exploration of the implicit self (Ogden, 2007, 2009).

Mindfulness is employed not as a solitary activity, conducted in the confines of one’s own mind, but as embedded within the verbal and nonverbal dance between patient and therapist (Ogden, 2014). Therapists first observe clients’ nonverbal behaviors and ask them to become aware of selected actions postures, expressions, and other nonverbal indicators as these emerge in the present moment during the therapy hour. As clients become mindful of their nonverbal behaviors, they are asked to describe their internal landscape—emotions, thoughts, images, memories, sensations—verbally as well. Therapists are invited to be a part of clients’ internal journeys, vicariously experiencing the varied scenery and sensing the many meanings. Through embedded relational mindfulness, awareness of the present moment is shared, mutual, and regulated interactively.

The sections that follow depict some basic somatic indicators that might be significant in clinical practice and describe the use of embedded relational mindfulness to discover their nuances and how to alter the somatic narrative within the therapeutic relationship. Indicators of the implicit self are noticed, outdated action sequences are interrupted, and new actions are initiated.

It is important for the reader to entertain the idea that specific interventions emerge spontaneously from what transpires experientially and implicitly within the therapeutic dyad. Philip Bromberg states that, most characteristically, he does not “plan” in advance what to do or say in the therapy hour, but rather “finds himself” doing or saying certain things that arise spontaneously from within the relationship (personal communication, December 21, 2010). His words and actions are not premeditated or generic techniques, but rather are emerging responses to what transpires in the here and now between himself and his patient. In the description of my own work that follows here, my interventions similarly “came to me” unbidden, arising from what occurred within the relationship. Although I can and will explain the theoretical rationale behind these interventions, they were neither premeditated nor consciously thought out. Although these interventions are “techniques” in principle, they are not generic. They never happen the same way twice, but come forth naturally and unexpectedly while both therapist and patient are subjectively experiencing each other. In other words, they are communicating their affective and somatic responsiveness to an experience of what is taking place within their relationship that is not processed cognitively but is known implicitly.

It takes intention, experience, and practice for the therapist to “know” which nonverbal cues are indicators and which are not. This “knowing” is not cognitive; rather the therapist finds him- or herself being drawn to a specific nonverbal cue, often without knowing why. Typically, later discoveries in the therapy hour reveal that the cue was a significant indicator of trauma and attachment history that reflects and sustains the implicit self.

The subsequent sections describe selected implicit self-indicators and examples of how to work with them in therapy: prosody, eye contact, facial expression, preparatory movement, arm movement, locomotion, posture, and proximity seeking. Obviously, this list is not by any means exhaustive, and many potentially significant indicators of the implicit self have been omitted: the angle and movement in the pelvis; the tilt of the head and the way it sits on the neck and shoulders; the angle, pronation, or supination of the feet, and how they push off the ground when walking; the tension in the knees and other joints; the way the arms hang from the shoulder girdle; range of motion of parts of the body; breathing patterns; and involuntary trembling and shaking often experienced by people with PTSD, to name a few (cf. Ogden, Minton, & Pain, 2006; Ogden & Fisher, 2015).

Prosody

Prosody pertains to how something is said rather than to the content itself. It includes rhythm, intonation, pitch, inflection, volume, tone of voice, tempo (fast, slow), resonance, intensity, crescendos and decrescendos, and even vocal sounds that are not words, such as “um,” and “uh-huh.” The pauses, rushes, hesitancies, and vocal punctuations that accentuate or downplay what is being said are all part of prosody, as is affective tone: sarcastic, soothing, patronizing, energizing, joyful, threatening, and so on. Sentences that have identical sequences of words may have different meanings that are disambiguated through prosody (Nespor, 2010). Discourse depends on prosody; in fact, “aprosodic sequences of words are hard to understand. To say the least, communication would not be effective without prosody” (Nespor, 2010, p. 382).

The way the words are said reveals volumes about implicit realms and forecasts of the future. “I am so angry,” said in a weak, defeated tone indicates a very different prediction from the same words each said with vigor and emphasis. Prosody reflects the explicit emotional state of the person in the moment, as well as unconscious emotional states. Anger might be revealed through the voice long before the person realizes he or she is angry; a tightening around the larynx may cause a thinning or constriction of the voice and be an early indicator of fear or anxiety.

Prosody may convey a command, request, plea, submission, dominance, or a question. I once observed a therapy session with Ron Kurtz as therapist. The patient’s pitch escalated at the end of every single sentence, as if he were asking a question. As the patient focused on the nonverbal indicator of his vocal pitch rising and even exaggerated it a bit, he almost immediately began to cry. He realized his prosody was asking the question, “Do you understand me?” The memories that emerged pertained to early emotionally charged attachment interactions in which he felt he was not seen for who he was and could not “get through” to his parents. Note that the meaning came from the patient, not the therapist. Meaning becomes discovered and conscious through mindful exploration of an indicator, rather than through the therapist’s interpretation. Patients’ own translation of the implicit meaning of the indicator is elicited, a translation that emerges from their own experience rather than from their own or their therapists’ analyses or interpretations.

In another example, my patient’s voice sounded childlike and dropped almost to a whisper as she reported that maybe she might be a little angry. “Cathy’s” prosody was a potent indicator of a childhood filled with abuse and shutting down. I found myself suggesting that she might explore saying “I’m angry” in a louder voice, which at first felt threatening to her and she became quieter—an old habit she had formed in an attempt to prevent drawing attention to herself. Later in the session, after we explored volume and prosody, she looked into my eyes (called a “right-hemisphere modality,” according to Lapides [2010]), which were encouraging and accepting, and said, “I’m angry” in a louder voice. She felt more empowered and began to reclaim a healthy righteous anger that she had abandoned long ago because it only made her father’s abuse worse. It is significant that nonverbal behaviors like Cathy’s childlike whisper not only affect the other person, but also affect Cathy herself, causing her to feel more and more disempowered and submissive.

In the therapeutic relationship, “right brain-to-right brain prosodic communications . . . act as an essential vehicle of implicit communications. . . . The right hemisphere is important in the processing of the ‘music’ behind our words” (Schore & Schore, 2007, Matching the patient’s prosody in terms of volume, tone, and pace is necessary to join and connect, and from there the therapist might slowly up- or downregulate through the same mechanisms. Ron Kurtz (1990) taught his students to speak in the simplest language possible to access early memories and process strong emotion. Lapides states that she knows to “keep [her] sentences simple as LH [left-hemisphere] processing is impaired at elevated levels of arousal and to rely on RH [right-hemisphere] non-verbal means to connect with [hyperaroused patients]” (2010, p. 9).

It bears repeating that all nonverbal indicators convey messages back and forth in the therapeutic dyad that are processed without conscious consideration. Imagine a male therapist who speaks to his female client in clipped, definitive statements and questions without much affect. She implicitly interprets his prosody as indicative of his authority and superiority, which triggers compliance in her and prosody that sounds like a little girl who needs the protection and approval of her father. Colluding together, the therapist feels protective and does not challenge his patient, but is unaware of this. A collusion such as this can lead to an impasse in the therapy; an enactment typically ensues that challenges the therapist to “wake up” and realize that what is going on in the therapy hour pertains to each party’s history and what is taking place between the two of them, instead of continuing to believe that what is going on between them pertains to the patient and her history alone (Bromberg, 2006).

Eye Contact

The eyes can speak louder than words. Prosodic communication can be confirmed or contradicted by such movements as downcast eyes, slow or rapid blinking, a flutter of the eyelashes, a look away and back. Proximity is fine-tuned by eye contact, bringing us closer or creating more distance. Eyes can be intent, as the absorbed gaze of a baby with the mother, or blank and unseeing, like the vacant stare of a person in shock. One patient’s eyes locked into mine as if her life depended on our eye contact. Her terrified gaze spoke of the huge risk she was taking in telling the “secret” of her abuse for the first time. Other patients scan the environment for potential threat cues, ever hypervigilant, and are unable to make eye contact for more than a fleeting second.

The eyes, like all nonverbal cues, change moment to moment in response to internal and environmental cues. A sudden tightening or narrowing of the eyes might indicate pain, aversion, disagreement, suspicion, or threat, whereas a widening of the eyes might signal excitement, surprise, or shock. Frequency, intensity, insistence on or aversion to eye contact, length of contact, and style (e.g., glancing, pupil dilation, blinks, wide eyed or shrouded, eyes angled downward or upward) can all be important indicators of the implicit self.

Eye contact can be frightening for trauma survivors, and patients may be “beset by shame and anxiety and terrified by being judged and ‘seen’ by the therapist” (Courtois, 1999, p. 190). In the consulting room, therapist and patient might experiment with making eye contact, being mindful of what happens internally and what changes relationally when one or the other looks away or closes his or her eyes. Repeated patterns of using the eyes can also be explored. One patient who frequently narrowed his eyes explored doing this voluntarily and mindfully and realized he always felt suspicious of me. He eventually traced this pattern back to emotionally charged memories of his unpredictable mother, which had left him feeling on guard, insecure, and suspicious in relationships. Another client, “Marley,” had suffered from chronic abuse throughout her childhood. She consistently avoided eye contact with me, only glancing at my face for a split second before looking away. At one point in therapy, I asked her what happened when our eyes met, and she became uncomfortable and withdrawn. The more she tried to make eye contact, the more silent and withdrawn she became. Eventually I asked her to notice what happened if I closed my eyes. Marley immediately became more verbal and relaxed, and she stated that she felt much safer when I had my eyes closed. The absence of eye contact provided the safety Marley needed to arouse her social engagement system.

Facial Expression

The human face has more highly refined and developed expressions than any other animal, which can make looking at faces extremely rewarding, demanding, and emotionally stimulating. The face is probably the first area of the body to reflect immediate affect, often showing emotion before we are aware of it. The ventral vagal complex governs the muscles of the face and is initially built upon a series of face-to-face interactions with an attachment figure that empathically regulates the infant’s arousal. The “neural regulation of [facial] muscles that provide important elements of social cueing are available to facilitate the social interaction with the caregiver and function collectively as an integrated social engagement system” (Porges, 2005, p. 36). Schore (1994) asserts that at around 8 weeks of age, the face-processing areas of the right hemisphere are activated, and face-to-face interactions remain an essential element of interactive regulation throughout the lifespan.

However, adequate dyadic affect regulation does not mean that the mother’s facial expressions consistently reflect attunement. Tronick and Cohn (1989) report that between 70 and 80% of face-to-face interactions between attachment figures and their infants can be mismatched. In the majority of cases, these mismatched moments are repaired quickly and any disorganization in the infant is alleviated (DiCorcia & Tronick, 2011). In an attuned interaction, each party rapidly and unconsciously adjusts their facial expression (as well as eye contact and prosody) in response to his or her own and the partner’s affective expressions, and mismatches are quickly repaired.

Research shows that basic emotions have reliable distinctive facial expressions across cultures (Ekman, 1978). However, though we can often be aware of our expression and what we are communicating to others, fleeting microexpressions can implicitly communicate emotional states without self-reflective consciousness. Thus, facial expressions can reveal both intended and unintended emotions. Microexpressions can be visible for as little as one-fifth of a second and can expose emotions that a person is not yet aware of or is trying to conceal. These expressions register implicitly, and “observers make inferences about intention, personality, and social relationship, and about objects in the environment” (Ekman, 2004, p. 412). This is especially significant in terms of the implicit communication between patient and therapist and may help to explain the frequent extreme sensitivity of the traumatized patient to the nuances of the therapist’s emotional states.

The remnants of traumatic experience are disclosed in the expressive indicators of unresolved shock: wide open eyes, raised eyebrows, frozen movement, or hypervigilance and tension around the eyes. Increased dorsal vagal tone of the feigned death defense shows clearly in faces that appear flat, with flaccid muscles that reveal little expression (Porges, 2011). In both shock and feigned death, facial expression can be greatly diminished, reflecting a compromised social engagement system. Additionally, clues to affective biases and the beliefs that go with them are etched into face, visible in chronic wrinkles, lines, and patterns: downturned mouth, lifted upper lip, furrowed brow, raised eyebrows, laugh lines, and so on.

“John” had a habit of frowning, and the parallel lines between his eyes were deeply etched although he was only in his 20s. I found myself drawn to these furrows and noticed that they seemed to deepen as he talked about his problems with his girlfriend. I asked him if he would be interested in exploring the frown. He experimented with exaggerating the frown and then relaxing his forehead, being mindful of the thoughts, emotions, and memories that emerged spontaneously as he did so. He saw an image of himself as a small boy hearing the sound of his father’s hand striking against his mother’s face as his parents argued. I asked him to notice if there were words that went with the frown, and he tearfully said, “What’s going to happen to us?” These were the words of a small, helpless boy terrified at the violence in the next room, fearing that his world was coming to an end. John said that his reaction to his present-day conflict with his girlfriend traced back to these early memories, realizing that his current reaction was overblown since he and his girlfriend had a strong, secure relationship. Eventually, he experimented with discussing his current relationship while inhibiting the frown, and he felt calmer. His frown had implicitly communicated the terror of the past to him, which had little bearing on his current situation. Of interest also is that John reported that his girlfriend had interpreted his frown as criticism of her, which triggered her own defensiveness.

Preparatory Movement

Like fleeting microexpressions of the face, small movements of the body can be significant indicators. Anticipatory movements are evident in the minute physical gestures that are made in preparation for a larger movement. These involuntary movement adjustments occur just prior to a voluntary movement. Preparatory movements are reliable signs that predict actions that are about to happen because they are dependent upon the planned or voluntary movement for the form they take (Bouisset, 1991). The first indicators of animal defensive responses and proximity-seeking actions frequently show up in barely perceptible physical movements that antecede a larger movement. Visible prior to the execution of full gross motor actions, these micromovements take a variety of forms: a tiny crouch before a leap, a slight clenching of a fist before the strike, an opening of a hand before a reach, a slight leaning forward, a slight arm movement toward the therapist. Such movements are reliable preparatory cues of actions sequences that “wanted to happen” but had not been fully executed in the original contexts.

Once the therapist catches a glimpse of such a movement, or the patient reports what appears to be a preparatory cue, the patient can voluntarily execute the action “that wants to happen” slowly and mindfully. As “Martin” recalled the first combat he experienced in Vietnam, his hands were resting quietly on his knees. I noticed his fingers lifting slightly just as he reported the “knowing” he had experienced that someone was aiming a gun at him, although he could not see the enemy. Martin’s eyes widened, he appeared frightened, and his arousal began to escalate. Rather than focus on the content, I asked Martin to momentarily put the narrative aside in order to focus his attention exclusively on his hands and be aware of what “wants to happen” somatically. Martin described a feeling that his arms wanted to lift upward. As I encouraged him to “allow” the movement, he said that his arms wanted to move upward in a protective gesture. In staying with this movement, Martin started to notice a slight change. Instead of covering his head with his arms and freezing in a habitual immobilizing defense, he said that he had a physical feeling in his arms of wanting to push away. Note that this feeling emerged from his awareness of his body, not as an idea or thought. I encouraged the slow enactment of this mobilizing defense that was not possible at the time of the trauma, holding a pillow against Martin’s hands for him to push against. It was important that Martin temporarily disregard all memory and simply focus on his body in order to find a way to push that felt “right.” By executing an empowering defensive action, his arousal was downregulated and his terror subsided. Martin’s internal locus of control was strengthened because he was the one in charge of how much pressure I should use in resisting his pushing with the pillow, what position to be in, how long to push, and so on.

Through awareness of these preparatory movements and following what the body wants to do, the possibility of a new response emerges, incipient during the original event, ready to be further developed into an action that is more flexible and empowering. The experience of this new action—what it felt like, the sense of oneself as it is executed—seems to have the effect of expanding the patient’s behavioral options in his or her life.

Arm Movements

In addition to preparatory actions, a variety of other positions and movements of the arms and hands can be significant indicators. Arms might be crossed over the chest, resting on the lap, or hanging limp at the side. Hands may be fidgeting, placed palm up or down, clenched or open, and so on. One of the most accessible indicators in this category is the simple act of reaching out, which can be executed in a variety of styles that reflects and sustain unsymbolized meaning: palm up, palm down, full arm extension or with bent elbow held close to the body, relaxed or rigid musculature, shoulders curved in or pulled back. If attachment figures are neglectful, a child may cease reaching out to them and depend more upon autoregulation than interactive regulation. Adaptive in that context, these action sequences implicitly predict that no one will respond to proximity-seeking behavior, resulting in the literal abandonment of an integrated, purposeful action of reaching out.

Often I ask patients to simply reach out with one or both arms as a diagnostic experiment as well as an avenue for working through relational issues. One patient reached out with a stiff arm, palm down, braced shoulders, and a rigid spine, whereas another patient reached out weakly, shoulders rounded, keeping her elbow by her waist rather than fully extending her arm. Yet another, always preoccupied with my availability, reached out eagerly, with intense need, leaning forward, both arms fully extended. All these movements reflected a childhood devoid of adequate regulation and support and the abandonment of an integrated, regulated reaching with the expectation of someone reaching appropriately back.

During the course of therapy, I was drawn to the tension in “Robert’s” arms and shoulders and his reports of his girlfriend’s complaints that he was emotionally withdrawn. I asked if he would be interested in noticing what happened as he reached out with his arm, as if to reach for another person. He said he immediately felt suspicious of my suggestion but was willing to try it. As he reached out with his left arm, his body reflected his words in its tension, slight leaning back, stiff movement, locked elbow, downward palm. His nonverbal message conveyed his discomfort and lack of expectation of a safe, empathic reception. Robert’s affect transitioned from suspicion to defensiveness as he stayed with the gesture, saying angrily there was no point in reaching out: “Why bother?” Over time, together we explored his emotionally painful early memories of a father who could abide no weakness or need in his son. Robert learned to abandon this gesture simply because it evoked disgust and criticism from his father. His course of therapy included learning to reach out in an integrated manner, arm relaxed, fully engaged, with eye contact and intent to make real contact with the other—an action that was explored first with anger, but eventually with great sadness.

In addition to reaching out, exploring a variety of other arm movements can be vehicles for change (cf. Ogden, 2009, Ogden et al., 2006). Grasping or beckoning motions; actions of pushing, hitting, and circular motions that define one’s personal boundary; expressive movements of opening the arms widely in gestures of anticipatory embrace or expansion; movements of self-touch, such as hugging oneself—all are significant and the manner in which they are executed reflects the implicit self. Whereas reaching out and grasping and pulling movements can be a challenge for many traumatized clients, holding on and being unable to let go can be equally challenging.

Locomotion

Locomotion, the literal act of walking from one place to another, can have a variety of qualities: plodding, springy, tottering, hurried, slow, deliberate, and so on. The angle of the feet and how they come in contact with the ground; the swing of the arms; the pelvic movement forward and back and side to side while walking; the tension in the feet, knee, and hip joints; and the angle of the body (leaning forward or backward, to one side or the other) can all be significant avenues of exploration of the implicit self (cf. Ogden & Fisher, 2015).

One patient walked stiffly, with very little movement through her pelvis, a pattern that we discovered originated in an attempt to conceal her femininity and sexuality in an abusive environment. In one session, she practiced swinging her hips as she walked, which initially elicited fear and increased hypervigalence, but eventually became pleasurable and fun as she learned to separate the present from the past. Another patient walked with a plodding, heavy gait and noticed that, with each step, her heel struck the ground forcefully, jarring her vertebrae. She hunched her shoulders and looked at the ground as she walked, limiting her vision and her engagement with her environment. This pattern reflected and sustained her feelings of hopelessness that had no content. In therapy, she first became aware of her habitual walking style and experienced the negative repercussions both emotionally (hopelessness) and physically (pain with the jarring effect of each moment of impact). Eventually, after processing the hopelessness that had no content, she began to practice a different, more adaptive way of walking: pushing off from the balls of her feet to get a spring in each step. We compared her plodding gait with a bouncy, “head-up” walk, exchanging her hunched shoulders and rounded spine for an upright, shoulders-down posture that encouraged eye contact and engagement with others.

A child in a traumatogenic environment might experience a futile impulse to escape abuse, but these defensive actions are not executed in situations when escape is impossible. The active, mobilizing “flight” response is abandoned in favor of the more adaptive (in that situation) immobilizing defenses of freeze or feigned death. Patients often report pervasive “trapped” feelings, which “Lisa” experienced through a literal sense of heaviness and immobility in her legs, coupled with a foggy, spacey feeling. I suggested that we stand and walk together to notice that our legs could carry us away from certain objects in the room, and toward others. Lisa soon said she felt more present, and observed that it was good to notice her legs. The experience of mobility was a simple resource that Lisa came back to again and again—it helped her feel less immobile and alleviated her foggy, spacey feeling.

Posture

Postural integrity involves the spine, which serves as an axis around which the limbs and head can move (cf. Ogden & Fisher, 2015). The spine is the physical core of the body; it provides support and stability to the entire physical structure and is grounded securely through the inside of the legs and feet. The first movements of an infant are initiated in the core of the body and radiate out to the periphery, then contract back inward to the movements that strengthen the core (Aposhyan, 2004; Cohen, 1993). Kurtz and Prestera note that the core also has a psychological meaning as the ‘”place inside” to which we may “go for sustenance” (1976, p. 33).

Posture can be upright and aligned, or slumped, twisted, braced, frozen, collapsed, slouched, and so on. A plumb line through the top of the head, middle of the ear, shoulder, hip joint, knee joint, and ankle can be imagined to assess postural alignment and integrity. When these points are in a straight line, each segment of the body supports the one above, and the body is balanced in gravity. Often this imaginary line is jagged as parts of the body are displaced from optimal alignment. Some bodies are bowed forward, others are bent backward; the head may jut forward, or the pelvis may be retracted. Without a strong and stable core, the spine may flex and droop, an indicator that might literally feel like “I can’t hold myself up” and might correspond with feelings of dependency, neediness, or passivity. Tronick’s Still Face experiments often demonstrate the loss of postural integrity as infants’ spines slump and sag when their mothers fail to respond to them. Many patients exhibit this same pattern.

Janet (1925) pointed out that the therapist must be able to discern the action that the patient is unable to execute, and then demonstrate the missing action. If the therapist’s posture is slumped, he or she will not be able to demonstrate an aligned posture or help the patient develop alignment. The recent discovery of mirror neurons brings this point home by illustrating that the observation of another’s movement stimulates corresponding neural networks in the observer, thus priming the observer for making the same action (Gallese, Fadiga, Fogassi, & Rizzolatti, 1996).

“Doug’s” spine began to slump even more than usual as he spoke of his wife. I found myself more interested in his droopy posture than the content, and asked him to become aware of it. He realized his posture reflected and maintained uncomfortable feelings of inferiority and helplessness, familiar feelings in his marriage. After exploring his early experiences of similar painful feelings in his family of origin, we stood up to experiment with the difference between his habitual posture and posture that was aligned and erect, where his head sits centered over his shoulders, his chest rests over his body’s lower half, his pelvis supports his torso, and his legs and feet are under his body. With practice of an upright posture, Doug’s thoughts started to become less negative, and his feelings of helplessness transformed into a “can do” (his words) attitude. Note that a change such as Doug experienced can help to transform the implicit self, but for more enduring change it was also necessary to address his painful past that brought about his feelings of inferiority and helplessness and the corresponding saggy posture.

Proximity

Infants and children need the proximity of a supportive other to meet their survival needs and protect them from danger. The psychobiological attachment system organizes proximity-seeking behaviors to secure the nearness of attachment figures. This innate system adjusts to the behavior of the attachment figures. If the attachment figure is unreliable, the proximity-seeking behaviors may become hyperactive. If the attachment figure is neglectful or unavailable, or punishing in the face of need or vulnerability, the proximity-seeking behaviors may become hypoactive.

A variety of factors in addition to attachment history contribute to personal proximity preferences: the situation, the specific individuals involved, gender, age, familiarity, content, and so on. Depending upon these factors, Hall, Harrigan, and Rosenthal state that “too much” or “too little” distance between interactants can be regarded as equally negative (1995, p. 21). The childhood attachment figures of traumatized patients usually responded inadequately to proximity needs by providing either too much or too little distance, or vacillated between these extremes. These patients have particular difficulty navigating proximity and seem to not recognize a felt sense of the appropriate distance between themselves and others.

Therapists can help develop patients’ awareness of internal somatic barometers to appropriate proximity (cf. Ogden & Fisher, 2015). One patient, “Jill,” told me that close proximity made her feel safe and requested that I move my chair nearer to her. However, when I did so, I noticed her muscles tightening, her breath becoming shallow, her body pulling back in her chair, and her eyes looking away. Jill and I agreed to contrast increased proximity with increased distance, and, to her surprise, she found that her body relaxed more when the distance between us was increased. Jill had initially thought that close proximity was preferable, but her implicit self told another story in its somatic narrative. We continued the experiment until she reported a felt sense of “rightness” in her body in terms of the distance between us, which turned out to be about 8–10 feet apart. Jill described this felt sense as one of relaxation, with deeper breathing, easier eye contact, and an internal feeling of well-being.

Negotiating physical distance is a fruitful task because traumatized individuals invariably need to learn about their proximity needs and preferences to be able to tolerate relationships. Patients who have experienced early relational trauma are rarely able to set appropriate distance between themselves and others. Frequently, I ask patients how close or far they prefer me to sit. Experiments (moving toward and away from my patient, or moving an object such as a pillow closer and farther away) can be conducted to explore automatic responses to proximity, such as bracing, moving backward, holding the breath, or changes in orienting or attention. With patients for whom the above experiments are too provocative, introducing simple exercises such as rolling a therapy ball or gently tossing a pillow toward them while they use their arms to push the object away can strengthen the capacity to execute the defensive action of pushing away that was usually not allowed in early relationships.

One patient first stood immobile, allowing the pillow I gently threw to hit her torso. Slowly, she practiced lifting her arms in a gesture of protection against the pillow hitting her body. (Note that when protective actions have incited the perpetrator to more violence in the past, as they did in her extremely abusive childhood, these actions are abandoned; executing them in the “safe” context of therapy can be terrifying, and patients need encouragement and practice to execute these actions.) This built the foundation upon which other proximity exercises could be introduced, such as her making a beckoning gesture and my slowly walking toward her, until she experienced a felt sense in her body that I was close enough. Then she could tell me to stop with her voice or by lifting her arms, palms open and extended outward in a “stop” gesture. It is important that the sense of suitable proximity is founded on the experienced somatic sense of preference, safety, and protection, rather than on analysis or ideas.

Self-States and Enactment

Integrated actions are abandoned or distorted when they are persistently ineffective in producing the desired outcome. If no one is there to reach back, we stop reaching out. If our attachment figures ridiculed us when we were vulnerable, we stop seeking proximity when we feel needy. If standing upright with our heads held high brought more abuse, we will slump and keep our heads down. Exploring alternative actions can bring forward a variety of self-states that are “inhospitable and even adversarial, sequestered from one another as islands of ‘truth,’ each functioning as an insulated version of reality that protectively defines what is ‘me’ at a given moment and forcing other self states that are inharmonious with its truth to become ‘not-me’” (Bromberg, 2010, p. 21).

When Robert explored reaching out, the self-state that had learned to inhibit that action became frightened and oppositional. Having made up its mind that others were never to be relied upon to respond to his need, this part of him believed reaching out to be hopeless and even threatening. New actions, like new words, “are often initially perceived from an adversarial perspective by at least one part of the self, sometimes with grave misgivings, sometimes with outright antagonism, and sometimes even with rage” (Bromberg, 2006, p. 52). Keep in mind that these actions are not simply physical exercises: They are rich with strong attachment-related emotions that were not regulated by the attachment figures in early childhood and/or with trauma-related emotions of terror and rage that accompany animal defenses. Processing these actions and their affects can ultimately encourage self-states to get to know one another and increase the ease of transitions between states.

It warrants reiterating that the therapist’s own nonverbal expressions and the self-states they represent have a strong impact on what takes place within the therapeutic relationship. Therapists tend to invite and interact with the parts of the patient with which they are most comfortable, disconnecting from and ignoring the patient’s self-states that they would rather not address (Bromberg, 2006). Physical actions that are familiar, easy for the therapist to execute, and do not challenge or stimulate the “not-me” self-states of the therapist are those that he or she is likely to explore in the patient, ignoring or rejecting actions would make him or her uncomfortable. If the therapist is uneasy with reaching out to others for support, and/or uneasy when others reach out to him or her, the therapist will be unlikely to explore this action with the patient. If he or she attempts to do so, the therapist will probably be unable to demonstrate an emotionally and physically integrated reaching action, so the exploration will have little chance of producing the explicitly desired outcome. But this is not cause for undue concern for the therapist who is interested in learning about his or her own participation in what takes place beyond the words. In fact, the real magic and healing power of clinical practice often emerge from the unformulated, unconscious impact of therapist and patient upon one another, which includes the influence of past childhood histories on both parties.

Therapy can be conceptualized as comprising two mutually created, simultaneous journeys (cf. Ogden, 2014). An explicit, conscious journey pertains to what the therapist believes he or she is doing as a clinician, supported by theory and technique. Therapeutic methods, meant to be learned but then be set aside and not reflected upon explicitly in the therapy hour, guide interventions that emerge spontaneously within the dyad. However, inevitably, the implicit selves of therapist and patient communicate beneath the words and even collide in therapeutic enactments. The implicit journey is elusive and unconscious, and although it may feel vaguely familiar, it usually leads relentlessly to outcomes that were not intended or predicted. For one client, “Ellen,” our implicit journey together became clear. Ellen had been forced to submit to extreme abuse during her childhood. A pattern of compliance continued into adulthood, long after that abuse was over. Ellen stated that she had great trouble feeling anger, and that when she did, she often turned it against herself through self-harm. As we explored her anger, Ellen discovered an impulse to push outward, along with the words, “Leave me alone.” She immediately felt strong and powerful, and I felt relieved. Ellen stated that she had not had much of a chance to practice any assertive action because assertion would have made the abuse at the hands of her father much worse. I suggested that we practice this action in therapy by giving her the opportunity to push away a pillow as I moved it toward her. Ellen agreed, but she was reluctant. I briefly asked if it was OK with her to practice, but I did not pay attention to the part of Ellen that (still) could not say no. She became compliant, and I, in my effort to “do more,” did not notice her compliance. I realized that my “pushing” her was a reflection of my own childhood with a demanding mother who conveyed that “more was better.” I failed to notice that Ellen was at the limit of her window of tolerance (Siegel, 1999) and at risk of dissociating. Our two histories collided in an enactment that continued to intensify until finally we realized together that Ellen was complying and becoming dysregulated.

The past is commonly reworked in a more powerful and substantial manner through processing an enactment than if the enactment had not occurred. The presence of both our pasts contributed to the enactment. My part reflected my childhood attempts to please my mother by doing more, and Linda’s part reflected her childhood pattern of submitting and complying to the wishes of others. Processing the enactment is possible when the therapist or the client (or both) “‘wakes up’ and feels that something is going on between himself and his patient (a here-and-now experience), rather than continuing to believe that the phenomenon is located solely in his patient, who is ‘doing the same thing again’” (Bromberg, 2006, p. 34). I “woke up” when Ellen’s eyes widened fearfully, and she abruptly sat down, shaking. At that moment, I realized that we had gone too far, and that interactive regulation was needed to bring her arousal back into a window of tolerance. At that moment, I was able to acknowledge the part of Ellen that was terrified and provide the reassurance that “nothing bad was going to happen” from executing that action. If Ellen had not experienced her compliance and my failure to notice her dysregulation, interactive repair could not have occurred, and it is the repair and working through of the enacted experience that provided the most beneficial therapeutic impact.

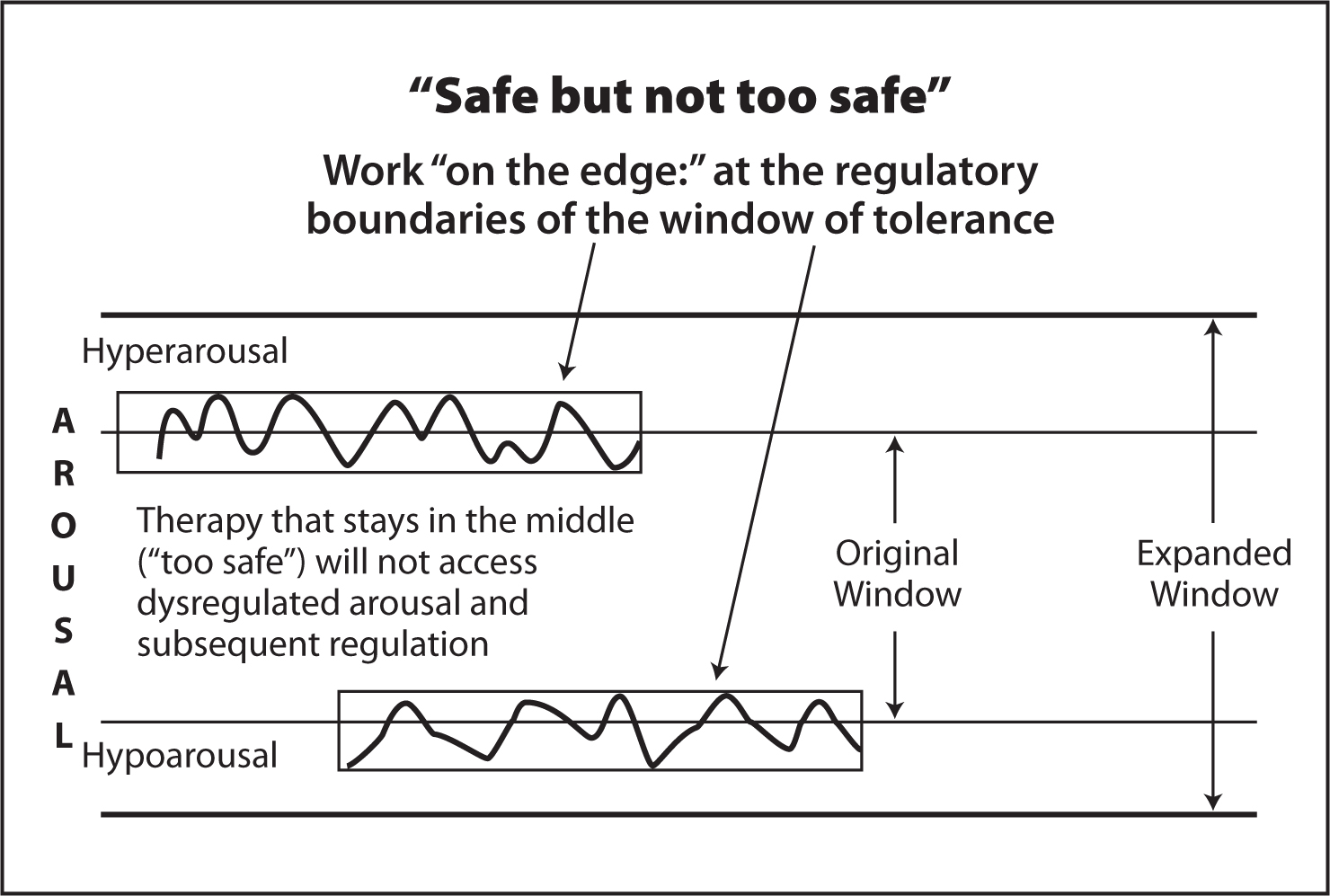

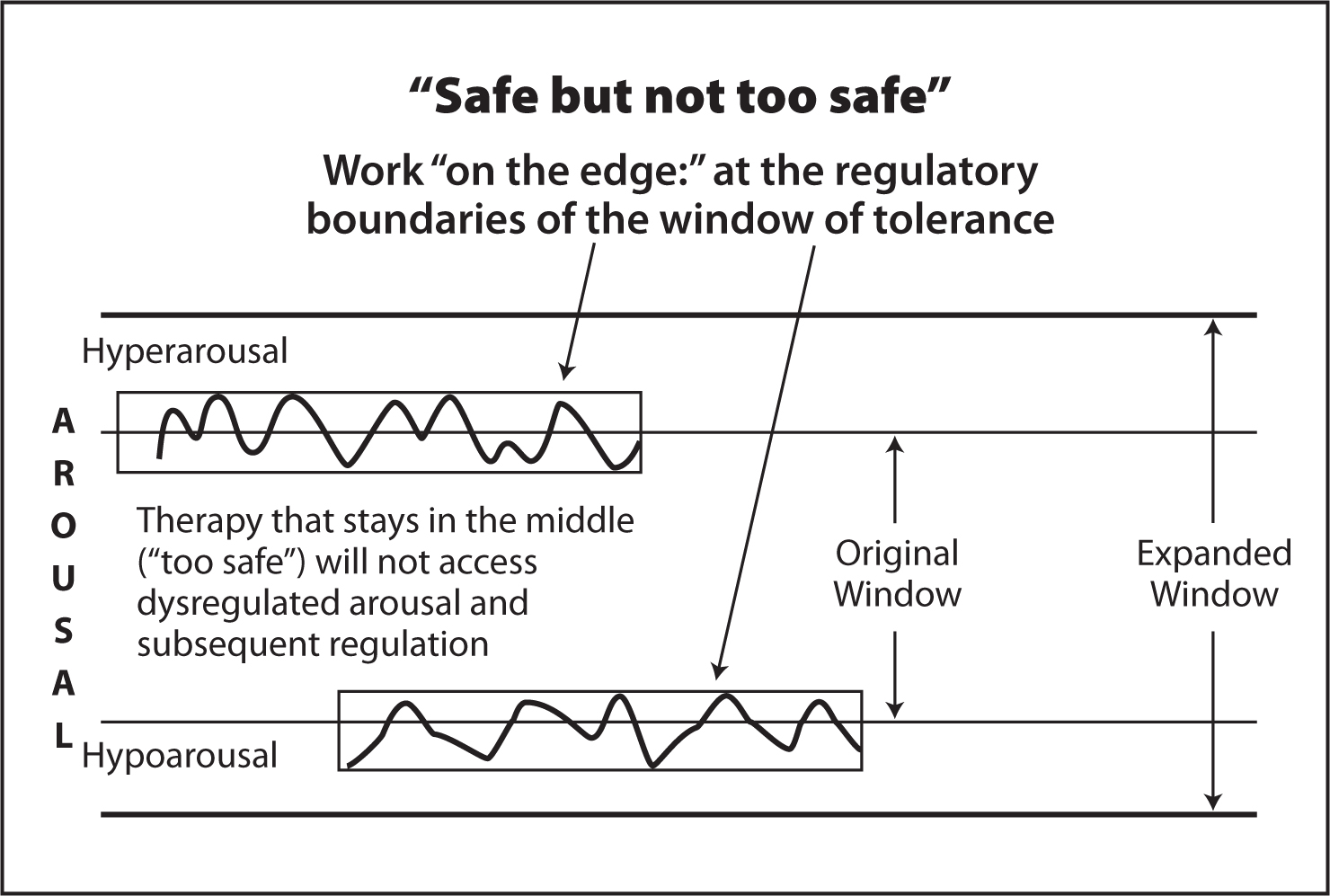

Bromberg (2006) emphasizes that the environment in which change can take place must be “safe but not too safe” for both therapist and patient. If the emotional and physiological arousal consistently remains in the middle of the window of tolerance (e.g., at levels typical of low fear and anxiety states), patients will not be able to expand their capacities because they are not challenging the window by contacting disturbing traumatic or affect-laden attachment issues in the here and now of the therapy hour. Similarly, therapists are challenged by the residue of their past histories that they thought were already resolved, but that emerge in enactments and empathic failures within the relationship. Thus both parties are at the regulatory boundaries of their own windows of tolerance (Schore, 2009). By working at the “edges” of the regulatory boundaries, the windows of both can be expanded.

It is the processing of each person’s implicit self within the relationship that provides the raw material for new experiences, new actions, and new meanings for both parties. Ellen and I participated together in an unfolding interaction within which we co-created a new experience and challenged early unsymbolized implicit relational knowing for both of us. Eventually, I “woke up” and recognized Ellen’s self-state that I had heretofore ignored—the one who was terrified of making an assertive action—by directly acknowledging her fear and reassuring her that this was a different situation from her childhood. This act of recognition challenged Ellen’s relational “knowing” that her fear would not be tended to, and that she needed comply to others’ wishes rather than assert herself. It also challenged my early relational knowing of never being “enough” and that I had to do more. This intersubjective process cannot be defined, identified, or predicted ahead of time, because it occurs within the context of what transpires within the dyad and thus requires a leap into the unknown not only for the patient, but for the therapist as well.

Conclusion

Visible and tangible nonverbal behaviors tell their own inimitable stories of the past and provide an ongoing source of implicit and explicit exploration in the therapy hour. The therapist listens not only to the verbal narrative, but also to the somatic narrative for the purpose of making the unconscious conscious as well as for “interacting at another level, an experience-near subjective level, one that implicitly processes moment to moment socio-emotional information at levels beneath awareness” (Schore, 2003b, p. 52). Along with the therapist’s implicit participation in the nonverbal conversation, explicit exploration of specific nonverbal behaviors provides an avenue to the patient’s unconscious. When we experiment with new actions to challenge outdated procedural learning, we challenge habitual implicit processing, including enactments, both explicitly through the use of words and also implicitly at a level at which words are not available and sometimes not needed for therapeutic change to occur. The intimacy and benefit of the therapist–client journey can be heightened by thoughtful attention to what is being spoken beneath the words, through the body.

References

Aposhyan, S. (2004). Bodymind psychotherapy: Principles, techniques, and practical applications. New York, NY: Norton.

Bainbridge-Cohen, B. (1993). Sensing, feeling and action. Northamption, MA: Contact.

Bouisset, S. (1991). Relationship between postural support and intentional movement: Biomechanical approach. Archives Internationales de Physiologie, de Biochimie et de Biophysique, 99, A77–A92.

Brazelton, T. (1989). The earliest relationship. Reading, MA: Addison–Wesley.

Bromberg, P. M. (2006). Awakening the dreamer: Clinical journeys. Mahwah, NJ: Analytic Press.

Bromberg, P. M. (2010). Minding the dissociative gap. Contemporary Psychoanalysis, 46(1), 19:31

Cortina, M., & Liotti, G. (2007). New approaches to understanding unconscious processes: Implicit and explicit memory systems. International Forum of Psychoanalysis, 16, 204–212.

Courtois, C. (1999). Recollections of sexual abuse: Treatment principles and guidelines. New York, NY: Norton.

DiCorcia, J. A., & Tronick, E. Z. (2011). Quotidian resilience: Exploring mechanisms that drive resilience from a perspective of everyday stress and coping. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 35(7), 1593-602.

Dijkstra, K., Kaschak, M. P., & Zwann, R. A. (2006). Body posture facilitates retrieval of autobiographical memories. Cognition, 102(1), 139–149.

Ekman, P. (1978). Facial signs: Facts, fantasies, and possibilities. In T. Sebeok (Ed.), Sight, sound and sense. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Ekman, P. (2004). Emotions revealed: Recognizing faces and feelings to improve communication and emotional life. New York, NY: Henry Holt.

Frewen, P. A., Neufeld, R. W., Stevent, T. K., & Lanius, R. A. (2010). Social emotions and emotional valence during imagery in women with PTSD: Affective and neural correlates. Journal of Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 2(2), 145–157.

Gallese, V., Fadiga, L., Fogassi, L., & Rizzolatti, G. (1996). Action recognition in the premotor cortex. Brain, 119, 593–609.

Grigsby, J., & Stevens, D. (2000). Neurodynamics of personality. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Hall, J., Harrigan, J., & Rosenthal, R. (1995). Nonverbal behavior in clinician–patient interaction. Applied & Preventive Psychology, 4, 21–37.

Janet, P. (1925). Principles of psychotherapy. London, UK: Allen & Unwin.

Krystal, H. (1978). Trauma and affects. Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, 33, 81–116.

Kurtz, R. (1990). Body-centered psychotherapy: The Hakomi method. Mendocino, CA: LifeRhythm.

Kurtz, R. (2010). Readings. Retrieved December 3, 2010, from http://hakomi.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/12/Readings-January-2010.pdf

Kurtz, R., & Prestera, H. (1976). The body reveals: An illustrated guide to the psychology of the body. New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Lanius, R. A., Williamson, P. C., Boksman, K., Densmore, M., Gupta, M.,...& Neufeld, R.W. (2002). Brain activation during script-driven imagery induced dissociative responses in PTSD: A functional magnetic resonance imaging investigation. Biological Psychiatry, 52, 305–311.

Lapides, F. (2010). The implicit realm in couples therapy: Improving right hemisphere affect-regulating capabilities. Journal of Clinical Social Work, published online May 20, 2010. Retrieved January 10, 2010, from http://www.francinelapides.com/newdocs4/Implicit_Realm_Couples_Therapy.pdf

LeDoux, J. (2002). Synaptic self: How our brains become who we are. New York, NY: Penguin.

Lyons-Ruth, K. (1998). Implicit relational knowing: Its role in development and psychoanalytic treatment. Infant Mental Health Journal, 19, 282–289.

Lyons-Ruth, K., Bronfman, E., & Parsons, E. (1999). Atypical attachment in infancy and early childhood among children at developmental risk: IV. Maternal frightened, frightening, or atypical behaviour and disorganized infant attachment patterns. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 64(3), 67–96.

Nespor, M. (2010). Prosody: An interview with Marina Nespor. ReVEL, 8(15). Retrieved December 23, 2010, from www.revel.inf.br/eng

Nijenhuis, E., & van der Hart, O. (1999a). Forgetting and reexperiencing trauma: From anesthesia to pain. In J. Goodwin & R. Attias (Eds.), Splintered reflections: Images of the body in trauma (pp. 33-66). Basic Books.

Nijenhuis, E., & van der Hart, O. (1999b). Somatoform dissociative phenomena: A Janetian perspective. In J. Goodwin & R. Attias (Eds.), Splintered reflections: Images of the body in trauma (pp. 89-128). Basic Books.

Ogden, P. (2007, March). Beyond words: A clinical map for using mindfulness of the body and the organization of experience in trauma treatment. Paper presented at Mindfulness and Psychotherapy Conference, Los Angeles, CA, UCLA/Lifespan Learning Institute.

Ogden, P. (2009). Emotion, mindfulness, and movement: Expanding the regulatory boundaries of the window of tolerance. In D. Fosha, D. Siegel, & M. Solomon (Eds.), The healing power of emotion: Perspectives from affective neuroscience and clinical practice (pp. 204-231). New York, NY: Norton.

Ogden, P. (2011). Beyond Words: A Sensorimotor Psychotherapy Perspective on Trauma Treatment. In Caretti V., Craparo G., Schimmenti (eds.), Psychological Trauma. Theory, Clinical and Treatment. Rome: A

Ogden, P. (2013). “Oltre le parole: la psicoterapia sensomotoria nel trattamento del trauma” (pp. 183-214). In V. Caretti, G. Craparo, A. Schimmenti (a cura di), Memorie traumatiche e mentalizzazione. Teoria, ricerca e clinica. Roma: Astrolabio.strolabio.

Ogden, P. (2013). Technique and beyond: Therapeutic enactments, mindfulness, and the role of the body. In D. J. Siegel & M. Solomon (Eds.), Healing moments in psychotherapy. New York, NY: Norton.

Ogden, P. (2014). Embedded relational mindfulness: A sensorimotor psychotherapy perspective on trauma treatment. In V. M. Follette, D. Rozelle, J. W. Hopper, D. I. Rome, & J. Briere (Eds.), Contemplative methods in trauma treatment: Integrating mindfulness and other approaches (pp. 227-242 ). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Ogden, P., & Fisher, J. (2015). Sensorimotor psychotherapy: Interventions for trauma and attachment. New York, NY: Norton.

Ogden, P., Minton, K., & Pain, C. (2006). Trauma and the body: A sensorimotor approach to psychotherapy. New York, NY: Norton.

Porges, S. W. (2005). The role of social engagement in attachment and bonding: A phylogenetic perspective. In C. Carter, L. Aknert, K. Grossman, S. Hirdy, M. Lamb, S. W. Porges, & N. Sachser (Eds.), From the 92nd Dahlem Workshop Report: Attachment and bonding—a new synthesis. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Porges, S. W. (2011). The polyvagal theory: Neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication, and self-regulation. New York, NY: Norton.

Schachner, D., Shaver, P., & Mikulincer, M. (2005). Patterns of nonverbal behavior and sensitivity in the context of attachment relationships. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 29(3), 141–169.

Schnall, S., & Laird, J. D. (2003). Keep smiling: Enduring effects of facial expressions and postures on emotional experience and memory. Cognition and Emotion 17(5), 787–797.

Schore, A. N. (1994). Affect regulation and the origin of the self: The neurobiology of emotional development. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Schore, A. N. (2003). Affect regulation and the repair of the self. New York, NY: Norton.

Schore, A. N. (2007). Modern attachment theory: The central role of affect regulation in development and treatment. Clinical Social Work, 36(1), 9-20.

Schore, A. N. (2009). Right-brain affect regulation: An essential mechanism of development, trauma, dissociation, and psychotherapy. In D. Fosha, D. Siegel, & M. Solomon (Eds.), The healing power of emotion: Affective neuroscience, development and clinical practice (pp. 112-144). New York, NY: W.W. Norton.

Schore, A. N. (2010). The right brain implicit self: A central mechanism of the psychotherapy change process. In J. Pertucelli (Ed.), Knowing, not-knowing, and sort-of-knowing: Psychoanalysis and the experience of uncertainty (pp. 117-202). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Schore, A. N. (2011). The right brain implicit self lies at the core of psychoanalysis. Psychoanalytic Dialogues21, 1–26.

Schore, A. N. (2012). The science of the art of psychotherapy. New York, NY: Norton.

Siegel, D. (1999). The developing mind. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Stepper, S., & Strack, F. (1993). Proprioceptive determinants of emotional and nonemotional feelings. Personality & Social Psychology, 64(2), 211–220.

Stern, D. (1985). The interpersonal world of the infant: A view from psychoanalysis and developmental psychology. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Tronick, E. Z. (2007). The neurobehavioral and social–emotional development of infants and children. New York, NY: Norton.

Tronick, E. Z., & Cohn, J. F. (1989). Infant–mother face-to-face interaction: Age and gender differences in coordination and the occurrence of miscoordination. Child Development, 60, 85–92.

* A version of this chapter first appeared in Caretti, Craparo, & Schimmenti (2011)