8

Trump Against the Guardrails

Donald Trump’s first year in office followed a familiar script. Like Alberto Fujimori, Hugo Chávez, and Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, America’s new president began his tenure by launching blistering rhetorical attacks on his opponents. He called the media the “enemy of the American people,” questioned judges’ legitimacy, and threatened to cut federal funding to major cities. Predictably, these attacks triggered dismay, shock, and anger across the political spectrum. Journalists found themselves at the front lines, exposing—but also provoking—the president’s norm-breaking behavior. A study by the Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics, and Public Policy found that the major news outlets were “unsparing” in their coverage of the Trump administration’s first hundred days. Of news reports with a clear tone, the study found, 80 percent were negative—much higher than under Clinton (60 percent), George W. Bush (57 percent), and Obama (41 percent).

Soon, Trump administration officials were feeling besieged. Not a single week went by in which press coverage wasn’t at least 70 percent negative. And amid swirling rumors about the Trump campaign’s ties to Russia, a high-profile special counsel, Robert Mueller, was appointed to oversee investigations into the case. Just a few months into his presidency, President Trump faced talk of impeachment. But he retained the support of his base, and like other elected demagogues, he doubled down. He claimed his administration was beset by powerful establishment forces, telling graduates of the U.S. Coast Guard Academy that “no politician in history, and I say this with great surety, has been treated worse or more unfairly.” The question, then, was how Trump would respond. Would an outsider president who considered himself to be under unwarranted assault lash out, as happened in Peru and Turkey?

President Trump exhibited clear authoritarian instincts during his first year in office. In Chapter 4, we presented three strategies by which elected authoritarians seek to consolidate power: capturing the referees, sidelining the key players, and rewriting the rules to tilt the playing field against opponents. Trump attempted all three of these strategies.

President Trump demonstrated striking hostility toward the referees—law enforcement, intelligence, ethics agencies, and the courts. Soon after his inauguration, he sought to ensure that the heads of U.S. intelligence agencies, including the FBI, the CIA, and the National Security Agency, would be personally loyal to him, apparently in the hope of using these agencies as a shield against investigations into his campaign’s Russia ties. During his first week in office, President Trump summoned FBI Director James Comey to a one-on-one dinner in the White House in which, according to Comey, the president asked for a pledge of loyalty. He later reportedly pressured Comey to drop investigations into his recently departed national security director, Michael Flynn, pressed Director of National Intelligence Daniel Coats and CIA Director Mike Pompeo to intervene in Comey’s investigation, and personally appealed to Coats and NSA head Michael Rogers to release statements denying the existence of any collusion with Russia (both refused).

President Trump also tried to punish or purge agencies that acted with independence. Most prominently, he dismissed Comey after it became clear that Comey could not be pressured into protecting the administration and was expanding its Russia investigation. Only once in the FBI’s eighty-two-year history had a president fired the bureau’s director before his ten-year term was up—and in that case, the move was in response to clear ethical violations and enjoyed bipartisan support.

The Comey firing was not President Trump’s only assault on referees who refused to come to his personal defense. Trump had attempted to establish a personal relationship with Manhattan-based U.S. Attorney Preet Bharara, whose investigations into money laundering reportedly threatened to reach Trump’s inner circle; when Bharara, a respected anticorruption figure, continued the investigation, the president removed him. After Attorney General Jeff Sessions recused himself from the Russia investigation and his deputy, Rod Rosenstein, appointed the respected former FBI Director Robert Mueller as special counsel to oversee the investigation, Trump publicly shamed Sessions, reportedly seeking his resignation. White House lawyers even launched an effort to dig up dirt on Mueller, seeking conflicts of interest that could be used to discredit or dismiss him. By late 2017, many of Trump’s allies were openly calling on him to fire Mueller, and there was widespread concern that he would soon do so.

President Trump’s efforts to derail independent investigations evoked the kind of assaults on the referees routinely seen in less democratic countries—for example, the dismissal of Venezuelan Prosecutor General Luisa Ortega, a chavista appointee who asserted her independence and began to investigate corruption and abuse in the Maduro government. Although Ortega’s term did not expire until 2021 and she could be legally removed only by the legislature (which was in opposition hands), the government’s dubiously elected Constituent Assembly sacked her in August 2017.

President Trump also attacked judges who ruled against him. After Judge James Robart of the Ninth Circuit of the U.S. Court of Appeals blocked the administration’s initial travel ban, Trump spoke of “the opinion of this so-called judge, which essentially takes law-enforcement away from our country.” Two months later, when the same court temporarily blocked the withholding of federal funds from sanctuary cities, the White House denounced the judgment as an attack on the rule of law by an “unelected judge.” Trump himself responded by threatening to break up the Ninth Circuit.

The president took an indirect swipe at the judiciary in August 2017 when he pardoned the controversial former Arizona sheriff Joe Arpaio, who was convicted of violating a federal court order to stop racial profiling. Arpaio was a political ally and a hero to many of Trump’s anti-immigrant supporters. As we noted earlier, the chief executive’s constitutional power to pardon is without limit, but presidents have historically exercised it with great restraint, seeking advice from the Justice Department and never issuing pardons for self-protection or political gain. President Trump boldly violated these norms. Not only did he not consult the Justice Department, but the pardon was clearly political—it was popular with his base. The move reinforced fears that the president would eventually pardon himself and his inner circle—something that was reportedly explored by his lawyers. Such a move would constitute an unprecedented attack on judicial independence. As constitutional scholar Martin Redish put it, “If the president can immunize his agents in this manner, the courts will effectively lose any meaningful authority to protect constitutional rights against invasion by the executive branch.”

The Trump administration also trampled, inevitably, on the Office of Government Ethics (OGE), an independent watchdog agency that, though lacking legal teeth, had been respected by previous administrations. Faced with the numerous conflicts of interest created by Trump’s business dealings, OGE director Walter Shaub repeatedly criticized the president-elect during the transition. The administration responded by launching attacks on the OGE. House Oversight Chair Jason Chaffetz, a Trump ally, even hinted at an investigation of Shaub. In May, administration officials tried to force the OGE to halt investigations into the White House’s appointment of ex-lobbyists. Alternately harassed and ignored by the White House, Shaub resigned, leaving behind what journalist Ryan Lizza called a “broken” OGE.

President Trump’s behavior toward the courts, law enforcement and intelligence bodies, and other independent agencies was drawn from an authoritarian playbook. He openly spoke of using the Justice Department and the FBI to go after Democrats, including Hillary Clinton. And in late 2017, the Justice Department considered nominating a special counsel to investigate Clinton. Despite its purges and threats, however, the administration could not capture the referees. Trump did not replace Comey with a loyalist, largely because such a move was vetoed by key Senate Republicans. Likewise, Senate Republicans resisted Trump’s efforts to replace Attorney General Sessions. But the president had other battles to wage.

The Trump administration also mounted efforts to sideline key players in the political system. President Trump’s rhetorical attacks on critics in the media are an example. His repeated accusations that outlets such as the New York Times and CNN were dispensing “fake news” and conspiring against him look familiar to any student of authoritarianism. In a February 2017 tweet, he called the media the “enemy of the American people,” a term that, critics noted, mimicked one used by Stalin and Mao. Trump’s rhetoric was often threatening. A few days after his “enemy of the people” tweet, Trump told the Conservative Political Action Committee:

I love the First Amendment; nobody loves it better than me. Nobody….But as you saw throughout the entire campaign, and even now, the fake news doesn’t tell the truth….I say it doesn’t represent the people. It never will represent the people, and we’re going to do something about it.

Do what, exactly? The following month, President Trump returned to his campaign pledge to “open up the libel laws,” tweeting that the New York Times had “disgraced the media world. Gotten me wrong for two solid years. Change libel laws?” When asked by a reporter whether the administration was really considering such changes, White House Chief of Staff Reince Priebus said, “I think that’s something we’ve looked at.” Ecuadorian President Rafael Correa used this approach. His multimillion-dollar defamation suits and jailing of journalists on charges of defamation had a powerfully chilling effect on the media. Although Trump dropped the libel issue, he continued his threats. In July, he retweeted an altered video clip made from old WWE footage of him tackling and then punching someone with a CNN logo superimposed on his face.

President Trump also considered using government regulatory agencies against unfriendly media companies. During the 2016 campaign, he had threatened Jeff Bezos, the owner of the Washington Post and Amazon, with antitrust action, tweeting: “If I become president, oh do they have problems.” He also threatened to block the pending merger of Time Warner (CNN’s parent company) and AT&T, and during the first months of his presidency, there were reports that White House advisors considered using the administration’s antitrust authority as a source of leverage against CNN. And finally, in October 2017, Trump attacked NBC and other networks by threatening to “challenge their license.”

There was one area in which the Trump administration went beyond threats to try to use the machinery of government to punish critics. During his first week in office, President Trump signed an executive order authorizing federal agencies to withhold funding from “sanctuary cities” that refused to cooperate with the administration’s crackdown on undocumented immigrants. “If we have to,” he declared in February 2017, “we’ll defund.” The plan was reminiscent of the Chávez government’s repeated moves to strip opposition-run city governments of their control over local hospitals, police forces, ports, and other infrastructure. Unlike the Venezuelan president, however, President Trump was blocked by the courts.

Although President Trump has waged a war of words against the media and other critics, those words have not (yet) led to action. No journalists have been arrested, and no media outlets have altered their coverage due to pressure from the government. Trump’s efforts to tilt the playing field to his advantage have been more worrying. In May 2017, he called for changes in what he called “archaic” Senate rules, including the elimination of the filibuster, which would have strengthened the Republican majority at the expense of the Democratic minority. Senate Republicans did eliminate the filibuster for Supreme Court nominations, clearing the way for Neil Gorsuch’s ascent to the Court, but they rejected the idea of doing away with it entirely.

Perhaps the most antidemocratic initiative yet undertaken by the Trump administration is the creation of the Presidential Advisory Commission on Election Integrity, chaired by Vice President Mike Pence but run by Vice Chair Kris Kobach. To understand its potential impact, recall that the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts prompted a massive shift in party identification: The Democratic Party became the primary representative of minority and first- and second-generation immigrant voters, while GOP voters remained overwhelmingly white. Because the minority share of the electorate is growing, these changes favor the Democrats, a perception that was reinforced by Barack Obama’s 2008 victory, in which minority turnout rates were unusually high.

Perceiving a threat, some Republican leaders came up with a response that evoked memories of the Jim Crow South: make it harder for low-income minority citizens to vote. Because poor minority voters were overwhelmingly Democratic, measures that dampened turnout among such voters would likely tilt the playing field in favor of Republicans. This would be done via strict voter identification laws—requiring, for example, that voters present a valid driver’s license or other government-issued photo ID upon arrival at the polling station.

The push for voter ID laws was based on a false claim: that voter fraud is widespread in the United States. All reputable studies have concluded that levels of such fraud in this country are low. Yet Republicans began to push for measures to combat this nonexistent problem. The first two states to adopt voter ID laws were Georgia and Indiana, both in 2005. Georgia congressman John Lewis, a longtime civil rights leader, described his state’s law as a “modern day poll tax.” An estimated 300,000 Georgia voters lacked the required forms of ID, and African Americans were five times more likely than whites to lack them. Indiana’s voter ID law, which Judge Terence Evans of the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals called “a not-too-thinly veiled attempt to discourage election day turnout by certain folks believed to skew Democratic,” was taken to the Supreme Court, where it was upheld in 2008. After that, voter ID laws proliferated. Bills were introduced in thirty-seven states between 2010 and 2012, and by 2016 fifteen states had adopted such laws, although only ten had them in effect for the election.

The laws were passed exclusively in states where Republicans controlled both legislative chambers, and in all but Arkansas, the governor was also a Republican. There is little doubt that minority voters were a primary target. Voter ID laws are almost certain to have a disproportionate impact on low-income minority voters: According to one study, 37 percent of African Americans and 27 percent of Latinos reported not possessing a valid driver’s license, compared to 16 percent of whites. A study by the Brennan Center for Justice estimated that 11 percent of American citizens (twenty-one million eligible voters) did not possess government-issued photo IDs, and that among African American citizens, the figure rose to 25 percent.

Of the eleven states with the highest black turnout in 2008, seven adopted stricter voter ID laws, and of the twelve states that experienced the highest rates of Hispanic population growth between 2000 and 2010, nine passed laws making it harder to vote. Scholars have just begun to evaluate the impact of voter ID laws, and most studies have found only a modest effect on turnout. But a modest effect can be decisive in close elections, especially if the laws are widely adopted.

That is precisely what the Presidential Advisory Commission on Election Integrity hopes to make happen. The Commission’s de facto head, Kris Kobach, has been described as America’s “premier advocate of vote suppression.” As Kansas’s secretary of state, Kobach helped push through one of the nation’s strictest voter ID laws. For Kobach, Donald Trump was a useful ally. During the 2016 campaign, Trump had complained that the election was “rigged,” and afterward, he made the extraordinary claim that he had “won the popular vote if you deduct the millions of people who voted illegally.” He repeated this point in a meeting with congressional leaders, saying that there had been between three and five million illegal votes. The claim was baseless: A national vote-monitoring project led by the media organization ProPublica found no evidence of fraud. Washington Post reporter Philip Bump scoured Nexis for documented cases of fraud in 2016 and found a total of four.

But President Trump’s apparent obsession with having “won” the popular vote converged with Kobach’s voter suppression goals. Kobach endorsed Trump’s claims, declaring that he was “absolutely correct” in asserting that the number of illegal votes exceeded Clinton’s margin of victory. (Kobach later said that “we will probably never know” who won the popular vote.) Kobach gained Trump’s ear, helped convince him to create the Commission, and was appointed to run it.

The Commission’s early activities suggested that its objective was voter suppression. First, it is collecting stories of fraud from across the country, which could provide political ammunition for state-level voter-restriction initiatives or, perhaps, for efforts to repeal the 1993 “Motor Voter” law. In effect, the Commission is poised to serve as a high-profile national mouthpiece for Republican efforts to pass tougher voter ID laws. Second, the Commission aims to encourage or facilitate state-level voter roll purges, which, existing research suggests, would invariably remove many legitimate voters. The Commission has already sought to cross-check local voter records to uncover cases of double registration, in which people are registered in more than one state. There are also reports that the Commission plans to use a Homeland Security database of green card and visa holders to scour the voter rolls for noncitizens. The risk, as one study shows, is that the number of mistakes—because of the existence of many people with the same name and birthdate—will vastly exceed the number of illegal registrations that are uncovered.

Efforts to discourage voting are fundamentally antidemocratic, and they have a particularly deplorable history in the United States. Although contemporary voter-restriction efforts are nowhere near as far-reaching as those undertaken by southern Democrats in the late nineteenth century, they are nevertheless significant. Because strict voter ID laws disproportionately affect low-income minority voters, who are overwhelmingly Democratic, they skew elections in favor of the GOP.

Trump’s Commission on Election Integrity did not carry out any concrete reforms in 2017, and its clumsy request for voter information was widely rebuffed by the states. But if the Commission proceeds with its project unchecked, it has the potential to inflict real damage on our country’s electoral process.

In many ways, President Trump followed the electoral authoritarian script during his first year. He made efforts to capture the referees, sideline the key players who might halt him, and tilt the playing field. But the president has talked more than he has acted, and his most notorious threats have not been realized. Troubling antidemocratic initiatives, including packing the FBI with loyalists and blocking the Mueller investigation, were derailed by Republican opposition and his own bumbling. One important initiative, the Advisory Commission on Election Integrity, is just getting off the ground, so its impact is harder to evaluate. Overall, then, President Trump repeatedly scraped up against the guardrails, like a reckless driver, but he did not break through them. Despite clear causes for concern, little actual backsliding occurred in 2017. We did not cross the line into authoritarianism.

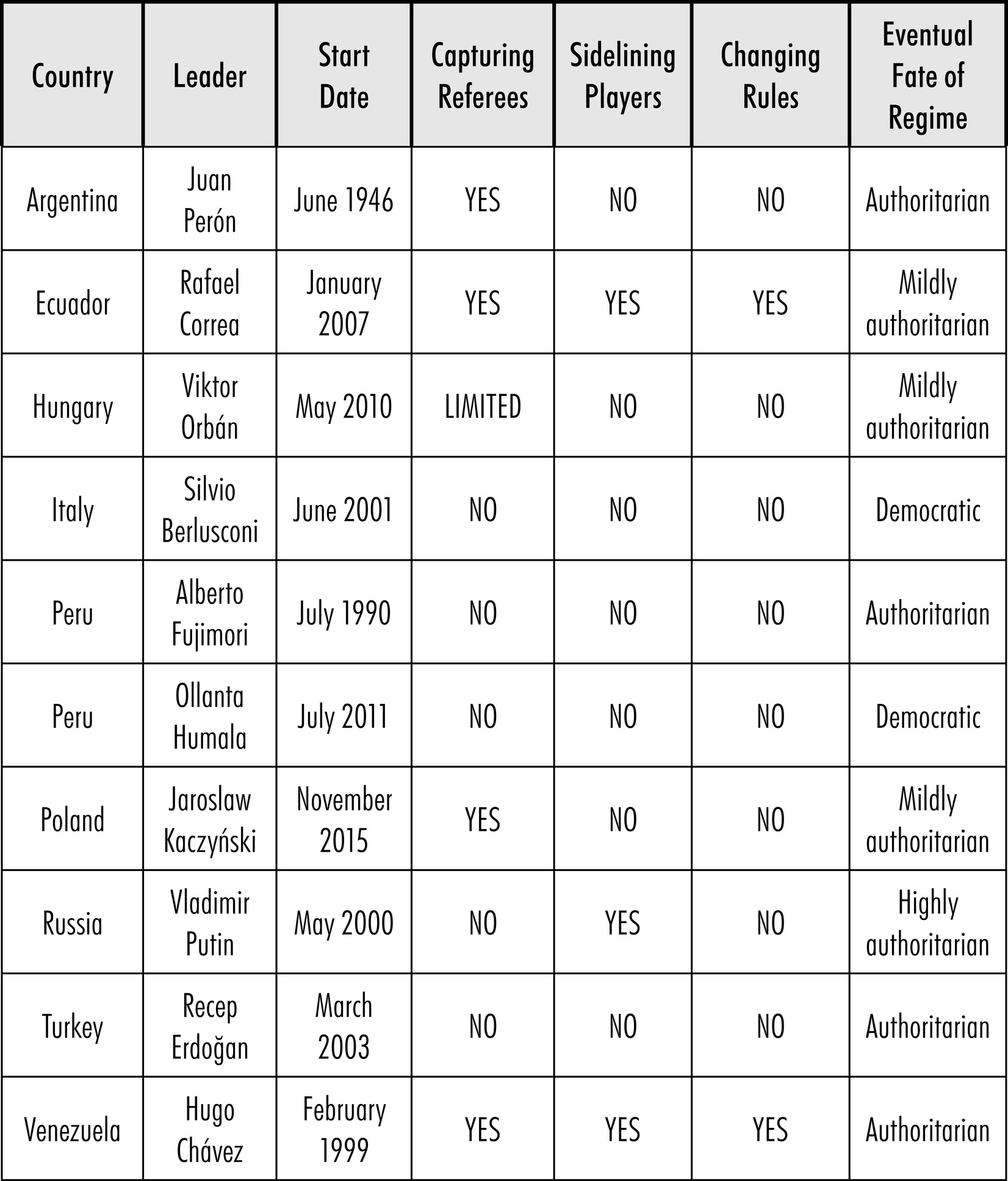

It is still early, however. The backsliding of democracy is often gradual, its effects unfolding slowly over time. Comparing Trump’s first year in office to those of other would-be authoritarians, the picture is mixed. Table 3 offers an illustrative list of nine countries in which potentially authoritarian leaders came to power via elections. In some countries, including Ecuador and Russia, backsliding was evident during the first year. By contrast, in Peru under Fujimori and Turkey under Erdoğan, there was no initial backsliding. Fujimori engaged in heated rhetorical battles during his first year as president but did not assault democratic institutions until nearly two years in. Breakdown took even longer in Turkey.

Table 3: The Authoritarian Report Card After One Year

Democracy’s fate during the remainder of Trump’s presidency will depend on several factors. The first is the behavior of Republican leaders. Democratic institutions depend crucially on the willingness of governing parties to defend them—even against their own leaders. The failure of Roosevelt’s court-packing scheme and the fall of Nixon were made possible, in part, when key members of the president’s own party—Democrats in Roosevelt’s case and Republicans in the case of Nixon—decided to stand up and oppose him. More recently, in Poland, the Law and Justice Party government’s efforts to dismantle checks and balances suffered a setback when President Andrzej Duda, a Law and Justice Party member, vetoed two bills that would have enabled the government to thoroughly purge and pack the supreme court. In Hungary, by contrast, Prime Minister Viktor Orbán faced little resistance from the governing Fidesz party as he made his authoritarian push.

The relationship between Donald Trump and his party is equally important, especially given the Republicans’ control over both houses of Congress. Republican leaders could choose to remain loyal. Active loyalists do not merely support the president but publicly defend even his most controversial moves. Passive loyalists retreat from public view when scandals erupt but still vote with the president. Critical loyalists try, in a sense, to have it both ways: They may publicly distance themselves from the president’s worst behavior, but they do not take any action (for example, voting in Congress) that will weaken, much less bring down, the president. In the face of presidential abuse, any of these responses will enable authoritarianism.

A second approach is containment. Republicans who adopt this strategy may back the president on many issues, from judicial appointments to tax and health care reform, but draw a line at behavior they consider dangerous. This can be a difficult stance to maintain. As members of the same party, they stand to benefit if the president succeeds—yet they realize that the president could inflict real damage on our institutions in the long term. They work with the president wherever possible while at the same time taking steps to ensure that he does not abuse power, allowing the president to remain in office but, they would hope, constraining him.

Finally, in principle, congressional leaders could seek the president’s removal. This would be politically costly for them. Not only does bringing down one’s own president risk accusations of treason from fellow partisans (imagine, for example, the responses of Sean Hannity and Rush Limbaugh), but it also risks derailing the party’s legislative agenda. It would hurt the party’s short-term electoral prospects, as it did after Nixon’s resignation. But if the threat coming from the presidency is severe enough (or if the president’s behavior starts to hurt their own poll numbers), party leaders may deem it necessary to bring down one of their own.

During President Trump’s first year in office, Republicans responded to presidential abuse with a mix of loyalty and containment. At first, loyalty predominated. But after the president fired James Comey in May 2017, some GOP senators moved toward containment, making it clear that they would not approve a Trump loyalist to succeed him. Republican senators also worked to ensure that an independent investigation into Russia’s involvement in the 2016 election would go forward. A few of them pushed quietly for the Justice Department to name a special counsel, and many of them embraced Robert Mueller’s appointment. When reports emerged that the White House was exploring ways of removing Mueller, and when some Trump loyalists called for Mueller’s removal, important Republican senators, including Susan Collins, Bob Corker, Lindsey Graham, and John McCain, came out in opposition. And when President Trump leaned toward sacking Attorney General Jeff Sessions, who, having recused himself, could not fire Mueller, GOP senators jumped to Sessions’s defense. Senate Judiciary Committee Chair Chuck Grassley said he would not schedule hearings for a replacement if Sessions was fired.

Although Senators Graham, McCain, and Corker hardly joined the opposition (each voted with Trump at least 85 percent of the time), they took important steps to contain the president. No Republican leaders sought the president’s removal in 2017, but as journalist Abigail Tracy put it, some of them appeared to have “found their own red line.”

Another factor affecting the fate of our democracy is public opinion. If would-be authoritarians can’t turn to the military or organize large-scale violence, they must find other means of persuading allies to go along and critics to back off or give up. Public support is a useful tool in this regard. When an elected leader enjoys, say, a 70 percent approval rating, critics jump on the bandwagon, media coverage softens, judges grow more reluctant to rule against the government, and even rival politicians, worried that strident opposition will leave them isolated, tend to keep their heads down. By contrast, when the government’s approval rating is low, media and opposition grow more brazen, judges become emboldened to stand up to the president, and allies begin to dissent. Fujimori, Chávez, and Erdoğan all enjoyed massive popularity when they launched their assault on democratic institutions.

To understand how public support could affect the Trump presidency, ask yourself: What if America were like West Virginia? West Virginia is the most pro-Trump state in the union. According to a Gallup poll, President Trump’s approval rating there averaged 60 percent in the first half of 2017, compared to 40 percent in favor of him nationwide. In the face of the president’s popularity, opposition to him withered in West Virginia—even among Democrats. Democratic senator Joe Manchin voted with President Trump 54 percent of the time through August 2017, more than any other Democrat in the Senate. The Hill listed Manchin among Trump’s “10 Biggest Allies in Congress.” The state’s Democratic governor, Jim Justice, went further: He switched parties. Embracing President Trump at a rally, Justice not only praised him as a “good man” with “real ideas” but dismissed the Russia investigation, declaring: “Have we not heard enough about the Russians?” If Democrats across the country behaved as they did in West Virginia, President Trump would face little resistance—even on the issue of foreign interference in our election.

The higher President Trump’s approval rating, the more dangerous he is. His popularity will depend on the state of the economy, as well as on contingent events. Events that put the government’s incompetence on display, such as the Bush administration’s inept response to Hurricane Katrina in 2005, can erode public support. But other developments, such as security threats, can boost it.

That brings us to a final factor shaping President Trump’s ability to damage our democracy: crisis. Major security crises—wars or large-scale terrorist attacks—are political game changers. Almost invariably, they increase support for the government. Citizens become more likely to tolerate, and even endorse, authoritarian measures when they fear for their security. And it’s not only average citizens who respond this way. Judges are notoriously reluctant to block presidential power grabs in the midst of crises, when national security is perceived to be at risk. According to political scientist William Howell, institutional constraints on President Bush disappeared in the wake of the 9/11 attacks, allowing Bush to “do whatever he liked to define and respond to the crisis.”

Security crises are, therefore, moments of danger for democracy. Leaders who can “do whatever they like” can inflict great harm upon democratic institutions. As we have seen, that is precisely what leaders such as Fujimori, Putin, and Erdoğan did. For a would-be authoritarian who feels unfairly besieged by opponents and shackled by democratic institutions, crisis opens up a window of opportunity.

In the United States, too, security crises have permitted executive power grabs, from Lincoln’s suspension of habeas corpus to Roosevelt’s internment of Japanese Americans to Bush’s USA PATRIOT Act. But there was an important difference. Lincoln, Roosevelt, and Bush were committed democrats, and at the end of the day, each of them exercised considerable forbearance in wielding the vast authority generated by crisis.

Donald Trump, by contrast, has rarely exhibited forbearance in any context. The chances of a conflict occurring on his watch are also considerable. They would be for any president—the United States fought land wars or suffered major terrorist attacks under six of its last twelve elected presidents. But given President Trump’s foreign policy ineptitude, the risks are especially high. We fear that if Trump were to confront a war or terrorist attack, he would exploit this crisis fully—using it to attack political opponents and restrict freedoms Americans take for granted. In our view, this scenario represents the greatest danger facing American democracy today.

Even if President Trump does not directly dismantle democratic institutions, his norm breaking is almost certain to corrode them. President Trump has, as David Brooks has written, “smashed through the behavior standards that once governed public life.” His party rewarded him for it by nominating him for president. In office, his continued norm violation has expanded the zone of acceptable presidential behavior, giving tactics that were once considered aberrant and inadmissible, such as lying, cheating, and bullying, a prominent place in politicians’ tool kits.

Presidential norm breaking is not inherently bad. Many violations are innocuous. In January 1977, Jimmy Carter surprised the police, the press, and the 250,000 Americans gathered to watch his inauguration when he and his wife walked the mile and a half from the Capitol to the White House. The New York Daily News described the Carters’ decision to abandon the “closed and armored limousine” as an “unprecedented departure from custom.” Ever since, it has become what the New York Times called “an informal custom” for the president-elect to at least step out of his protected limousine during the inaugural parade to show that he is “the people’s president.”

Norm breaking can also be democratizing: In the 1840 presidential election, William Henry Harrison broke tradition by going out and campaigning among voters. The previous norm had been for candidates to avoid campaigning, preserving a Cincinnatus-like fiction that they harbored no personal ambition for power—but limiting voters’ ability to get to know them.

Or take another example: In 1901, a routine White House press release was issued on behalf of new president Theodore Roosevelt headlined, “Booker T. Washington of Tuskegee, Alabama, dined with the President last evening.” While prominent black political leaders had visited the White House before, a dinner with a leading African American political figure was, as one historian has described it, a violation of “the prevailing social etiquette of white domination.” The response was immediate and vicious. One newspaper described it as “the most damnable outrage which has ever been perpetrated by any citizen of the United States.” Senator William Jennings Bryan commented, “It is hoped that both of them [Roosevelt and Washington] will upon reflection, realize the wisdom of abandoning their purpose to wipe out race lines.” In the face of the uproar, the White House’s press operation first denied the event happened, later said it had “merely” been a lunch, and then defended it by saying that at least no women had been present.

Because societal values change over time, a degree of presidential norm breaking is inevitable—even desirable. But Donald Trump’s norm violations in his first year of office differed fundamentally from those of his predecessors. For one, he was a serial norm breaker. Never has a president flouted so many unwritten rules so quickly. Many of the transgressions were trivial—President Trump broke a 150-year White House tradition by not having a pet. Others were more ominous. Trump’s first inaugural address, for example, was darker than such addresses typically are (he spoke, for example, of “American carnage”), leading former President George W. Bush to observe: “That was some weird shit.”

But where President Trump really stands out from his predecessors is in his willingness to challenge unwritten rules of greater consequence, including norms that are essential to the health of democracy. Among these are long-standing norms of separating private and public affairs, such as those governing nepotism. Existing legislation, which prohibits presidents from appointing family members to the cabinet or agency positions, does not include White House staff positions. So Trump’s appointment of his daughter, Ivanka, and son-in-law, Jared Kushner, to high-level advisory posts was technically legal—but it flouted the spirit of the law.

There were also norms regulating presidential conflicts of interest. Because presidents must not use public office for private enrichment, those who own businesses must separate themselves from these enterprises before they take office. Yet the laws governing such separation are surprisingly lax. Government officials are not technically required to divest themselves of their holdings, but only to recuse themselves from decisions that affect their interests. It has become standard practice for government officials to simply divest themselves, however, to avoid even the appearance of a wrongdoing. President Trump exercised no such forbearance, despite his unprecedented conflicts of interest. He granted his sons control over his business holdings, in a move deemed vastly insufficient by government ethics officials. The Office of Government Ethics reported receiving 39,105 public complaints involving Trump administration conflicts of interest between October 1, 2016, and March 31, 2017, a massive increase over the same period in 2008–2009 (when President Obama took office), when just 733 complaints were recorded.

President Trump also violated core democratic norms when he openly challenged the legitimacy of elections. Although his claim of “millions” of illegal voters was rejected by fact checkers, repudiated by politicians from both parties, and dismissed as baseless by social scientists, the new president repeated it in public and in private. No major politician in more than a century had questioned the integrity of the American electoral process—not even Al Gore, who lost one of the closest elections in history at the hands of the Supreme Court.

False charges of fraud can undermine public confidence in elections—and when citizens do not trust the electoral process, they often lose faith in democracy itself. In Mexico, after the losing presidential candidate, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, insisted that the 2006 election was stolen from him, confidence in Mexico’s electoral system declined. A poll taken prior to the 2012 presidential election found that 71 percent of Mexicans believed that fraud could be in play. In the United States, the figures were even more dramatic. In a survey carried out prior to the 2016 election, 84 percent of Republican voters said they believed a “meaningful amount” of fraud occurred in American elections, and nearly 60 percent of Republican voters said they believed illegal immigrants would “vote in meaningful amounts” in November. These doubts persisted after the election. According to a July 2017 Morning Consult/Politico poll, 47 percent of Republicans believed that Trump won the popular vote, compared to 40 percent who believed Hillary Clinton won. In other words, about half of self-identified Republicans said they believe that American elections are massively rigged. Such beliefs may be consequential. A survey conducted in June 2017 asked, “If Donald Trump were to say that the 2020 presidential election should be postponed until the country can make sure that only eligible American citizens can vote, would you support or oppose postponing the election?” Fifty-two percent of Republicans said they would support postponement.

President Trump also abandoned basic rules of political civility. He broke with norms of postelection reconciliation by continuing to attack Hillary Clinton. He also violated the unwritten rule that sitting presidents should not attack their predecessor. At 6:35 A.M. on March 4, 2017, President Trump tweeted, “Terrible! Just found out that Obama had my ‘wires tapped’ in Trump Tower just before the victory. Nothing found. This is McCarthyism!” He followed up half an hour later with: “How low has President Obama gone to tapp [sic] my phones during the very sacred election process. This is Nixon/Watergate. Bad (or sick) guy!”

Perhaps President Trump’s most notorious norm-breaking behavior has been lying. The idea that presidents should tell the truth in public is uncontroversial in American politics. As Republican consultant Whit Ayers likes to tell his clients, candidates seeking credibility must “never deny the undeniable” and “never lie.” Given this norm, politicians typically avoid lying by changing the topic of debate, reframing difficult questions, or only partly answering them. President Trump’s routine, brazen fabrications are unprecedented. His tendencies were manifest during the 2016 campaign. PolitiFact classified 69 percent of his public statements as “mostly false” (21 percent), “false” (33 percent), or “pants on fire” (15 percent). Only 17 percent were coded as “true” or “mostly true.”

Trump continued to lie as president. Tracing all the president’s public statements since taking office, the New York Times showed that even using a conservative metric—demonstrably false statements, as opposed to merely dubious ones—President Trump “achieved something remarkable”: He made at least one false or misleading public statement every single day of his first forty days in office. No lie is too obvious. President Trump claimed the largest Electoral College victory since Ronald Reagan (in fact, George H. W. Bush, Clinton, and Obama all won by larger margins than he did); he claimed to have signed more bills in his first six months than any other president (he was well behind several presidents, including George H. W. Bush and Clinton). In July 2017, he bragged that the head of the Boy Scouts told him he had “made the greatest speech ever made to them,” only to have the claim disputed immediately by the Boy Scouts organization itself.

President Trump himself did not pay much of a price for his lies. In a political and media environment in which engaged citizens increasingly filter events through their own partisan lenses, his supporters did not come to view him as dishonest during the first year of his presidency. For our political system, however, the consequences of his dishonesty are devastating. Citizens have a basic right to information in a democracy. Without credible information about what our elected leaders do, we cannot effectively exercise our right to vote. When the president of the United States lies to the public, our access to credible information is jeopardized, and trust in government is eroded (how could it not be?). When citizens do not believe their elected leaders, the foundations of representative democracy weaken. The value of elections is diminished when citizens have no faith in the leaders they elect.

Exacerbating this loss of faith is President Trump’s abandonment of basic norms of respect for the media. An independent press is a bulwark of democratic institutions; no democracy can live without it. Every American president since Washington has done battle with the media. Many of them privately despised it. But with few exceptions, U.S. presidents have recognized the media’s centrality as a democratic institution and respected its place in the political system. Even presidents who scorned the media in private treated it with a certain minimum of respect and civility in public. This basic norm gave rise to a host of unwritten rules governing the president’s relationship with the press. Some of these norms—such as waving to the press corps before boarding Air Force One—were superficial, but others, such as holding press conferences accessible to all members of the White House press corps, were more significant.

President Trump’s public insults of media outlets and even individual journalists were without precedent in modern U.S. history. He described the media as “among the most dishonest human beings on Earth,” and repeatedly accused such critical news outlets as the New York Times, the Washington Post, and CNN of lying or delivering “fake news.” Trump was not above personal attacks. In June 2017, he went after television host Mika Brzezinski and her cohost Joe Scarborough in a uniquely vitriolic tweetstorm:

I heard poorly rated @Morning_Joe speaks badly of me (don’t watch anymore). Then how come low I.Q. Crazy Mika, along with Psycho Joe, came…

…to Mar-a-Lago 3 nights in a row around New Year’s Eve, and insisted on joining me. She was bleeding badly from a face-lift. I said no!

Even Richard Nixon, who privately viewed the media as “the enemy,” never made such public attacks. To find comparable behavior in this hemisphere one must look at Hugo Chávez and Nicolás Maduro in Venezuela or Rafael Correa in Ecuador.

The Trump administration also broke established norms by selectively excluding reporters from press events. On February 24, 2017, Press Secretary Sean Spicer barred reporters from the New York Times, CNN, Politico, BuzzFeed, and the Los Angeles Times from attending an untelevised press “gaggle,” while handpicking journalists from smaller but sympathetic outlets such as the Washington Times and One America News Network to round out the pool. The only modern precedent for such a move was Nixon’s decision to bar the Washington Post from the White House after it broke the Watergate scandal.

In 1993, New York’s Democratic senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, a former social scientist, made an incisive observation: Humans have a limited ability to cope with people behaving in ways that depart from shared standards. When unwritten rules are violated over and over, Moynihan observed, societies have a tendency to “define deviancy down”—to shift the standard. What was once seen as abnormal becomes normal.

Moynihan applied this insight, controversially, to America’s growing social tolerance for single-parent families, high murder rates, and mental illness. Today it can be applied to American democracy. Although political deviance—the violation of unwritten rules of civility, of respect for the press, of not lying—did not originate with Donald Trump, his presidency is accelerating it. Under President Trump, America has been defining political deviancy down. The president’s routine use of personal insult, bullying, lying, and cheating has, inevitably, helped to normalize such practices. Trump’s tweets may trigger outrage from the media, Democrats, and some Republicans, but the effectiveness of their responses is limited by the sheer quantity of violations. As Moynihan observed, in the face of widespread deviance, we become overwhelmed—and then desensitized. We grow accustomed to what we previously thought to be scandalous.

Furthermore, Trump’s deviance has been tolerated by the Republican Party, which has helped make it acceptable to much of the Republican electorate. To be sure, many Republicans have condemned Trump’s most egregious behavior. But these one-off statements are not very punitive. All but one Republican senator voted with President Trump at least 85 percent of the time during his first seven months in office. Even Senators Ben Sasse of Nebraska and Jeff Flake of Arizona, who often strongly condemned the president’s norm violations, voted with him 94 percent of the time. There is no “containment” strategy for an endless stream of offensive tweets. Unwilling to pay the political price of breaking with their own president, Republicans find themselves with little alternative but to constantly redefine what is and isn’t tolerable.

This will have terrible consequences for our democracy. President Trump’s assault on basic norms has expanded the bounds of acceptable political behavior. We may already be seeing some of the consequences. In May 2017, Greg Gianforte, the Republican candidate in a special election for Congress, body-slammed a reporter from The Guardian who was asking him about health care reform. Gianforte was charged with misdemeanor assault—but he won the election. More generally, a YouGov poll carried out for The Economist in mid-2017 revealed a striking level of intolerance toward the media, especially among Republicans. When asked whether or not they favored permitting the courts to shut down media outlets for presenting information that is “biased or inaccurate,” 45 percent of Republicans who were polled said they favored it, whereas only 20 percent were opposed. More than 50 percent of Republicans supported the idea of imposing fines for biased or inaccurate reporting. In other words, a majority of Republican voters said they support the kind of media repression seen in recent years in Ecuador, Turkey, and Venezuela.

Two National Rifle Association recruiting videos were released in the summer of 2017. In the first video, NRA spokeswoman Dana Loesch speaks about Democrats and the use of force:

They use their schools to teach children that their president is another Hitler. They use their movie stars and singers and comedy shows and award shows to repeat their narrative over and over again. And then they use their ex-president to endorse the “resistance.” All to make them march, to make them protest, to make them scream racism and sexism and xenophobia and homophobia. To smash windows, to burn cars, to shut down interstates and airports, bully and terrorize the law-abiding, until the only option left is for the police to do their jobs and stop the madness. And when that happens, they use it as an excuse for their outrage. The only way we stop this, the only way we save our country and our freedom, is to fight the violence of lies with the clenched fist of truth.

In the second video, Loesch issues a not-so-subtle warning of violence against the New York Times:

We’ve had it with your pretentious…assertion that you are in any way truth- or fact-based journalism. Consider this the shot across your proverbial bow….In short, we’re coming for you.

The NRA is not a small, fringe organization. It claims five million members and is closely tied to the Republican Party—Donald Trump and Sarah Palin are lifetime members. Yet it now uses words that in the past we would have regarded as dangerously politically deviant.

Norms are the soft guardrails of democracy; as they break down, the zone of acceptable political behavior expands, giving rise to discourse and action that could imperil democracy. Behavior that was once considered unthinkable in American politics is becoming thinkable. Even if Donald Trump does not break the hard guardrails of our constitutional democracy, he has increased the likelihood that a future president will.