The Miracle of Dunkirk

In nine harrowing days, Allied commanders staged the largest evacuation in history, saving some 300,000 troops from the Nazis

HOME SAFE Rescued soldiers arrived home in London on May 31, 1940.

Would They Make It Out?

The first day ended grimly, with only 7,500 men rescued. But a narrow jetty offered hope

SINGLE FILE At times, lines of soldiers waiting in the water and on the beaches stretched two miles long, but the troops were orderly and patient. “You had the impression of people standing waiting for a bus,” said signaler Alfred Baldwin.

The first Dunkirk evacuations began inauspiciously on Monday, May 27, when Captain William Tennant, a logistics expert deployed to organize the loading of soldiers, arrived as German bombers attacked the harbor. Tennant and his team of 160 survived, but on disembarking, they encountered chaos. Terrorized soldiers, some of them deserters, some from rearguard units, skittered around the beach, uncertain of how to proceed. The dock facilities had been destroyed, and during that first bloody day, the Luftwaffe would kill 1,000 residents of Dunkirk and many Allied troops. The process of transporting soldiers in small boats to the larger ships was painstakingly slow. By sundown, only about 7,500 men had been rescued. Things began to improve when Tennant realized that a narrow jetty, 1,400 yards long and just five feet wide, could substitute as a dock. The first boat to tie up at the jetty, or the East Mole, as the British called it, boarded 950 soldiers in less than an hour.

The next day, Tuesday, May 28, went better. Cloudy weather and black smoke from burning oil storage tanks hampered visibility for the German bombers. Tennant’s team grew more proficient in organizing the men and navigating the harbor to avoid exploding mines and collisions with other boats. Some 18,000 men were evacuated, with minimal casualties.

On Wednesday, another 47,000 soldiers were evacuated, but the day was also marred by loss of life and matériel. Some 600 soldiers and crew were killed when two British destroyers were sunk before dawn. The Wakeful was hit first, by a German E-boat, a torpedo-bearing coastal craft. A submarine torpedo struck the Grafton after it picked up 35 surviving crew members from the Wakeful. When the skies cleared later in the day, the Luftwaffe resumed its attacks, repeatedly bombing and eventually sinking a third destroyer, the Grenade, and killing another 18 soldiers. Finally, the largest ship involved in the evacuation, the cargo steamer Clan MacAlister, took two direct hits from Stuka dive-bombers and had to be abandoned.

Thursday and Friday, the final two days in May, were perhaps the best for the Allies, as poor visibility limited the Luftwaffe and mostly calm seas aided the loading onto the boats. Two additional factors came into play. First, more small ships arrived to carry soldiers to the larger boats in the harbor; and second, Tennant and his team constructed makeshift piers out of damaged trucks and other equipment, which facilitated the loading process. Some 54,000 were evacuated on Thursday, including nearly 30,000 from the beaches; on Friday, another 68,000 were evacuated, despite a heavy swell in the morning that hampered the little boats and the return of clear skies in the afternoon, which brought the German planes back into action.

The scene on the beaches became hellish. Human corpses were everywhere, some covered, many buried and marked by an upturned rifle, others left to float in the water. Abandoned vehicles and the bodies of dead horses littered the sand. Food was scarce—some troops went four or five days without eating. Overhead, obscured by the smoke and too high to be seen by BEF soldiers on the ground, the RAF did its best to keep the German Stukas and Messerschmitts at bay.

COVER OF DARKNESS Cloudy skies—and nighttime evacuation—usually meant less danger from the Luftwaffe for the exposed troops on the beaches.

Unconventional Leaders

General Sir Ronald Forbes Adam

ONE OF several key officers in the evacuation, Adam was in charge of establishing and maintaining the defensive perimeter around Dunkirk. Adam had been educated at Eton and the Royal Academy Woolwich before serving in France during World War I and being awarded the Distinguished Service Order (DSO), the most prestigious medal awarded to British officers for exceptional bravery in combat. He was a close confidante and friend of Alan Brooke, commander of the BEF’s II Corps, which retained him as an important adviser throughout the war years, despite Churchill’s opinion that Adam’s progressive views made him too radical for military service. Among his more iconoclastic opinions: that soldiers should be chosen by a professional selection board based on psychological testing for leadership skills and initiative; that exceptional officers could be recruited from every social class; and that soldiers should be required to participate in compulsory discussion groups intended to produce better educated, more motivated troops.

General Alan Brooke

BORN IN France to an aristocratic Irish family, Brooke was sensitive, introspective, even shy, throughout his career. He was also one of Britain’s most talented military strategists and highly opinionated. He had little confidence in the fighting skills of the French, wondering in his diary “whether the French are still a firm enough nation to again take their part in seeing this war through” and noting of the French soldiers that their “slovenliness, dirtyness and inefficiency are I think worse than ever.” Brooke similarly doubted the capabilities of Lord Gort, his superior officer, whom he considered obsessed with minutiae. According to Brooke, Gort had the brain “of a glorified boy scout.” Brooke—or Brookie as he was known—was popular through the rank and file of the BEF’s II Corps, which he commanded at Dunkirk. His quick action defending the northern flank after the surrender of Belgian troops on May 28 may have been the single most important action of the campaign. Gort considered Brooke too pessimistic about British prospects in France, but he came to accept Brooke’s view that an evacuation was necessary.

Captain William Tennant

TENNANT ARRIVED in Dunkirk on May 26 aboard the destroyer Wolfhound and was given the job of organizing the men on the beaches and overseeing the loading of soldiers onto the ships. His decision to use the jetty known as the East Mole as a dispersal point, along with his many efforts to streamline the process, was critical in enabling large numbers of soldiers to safely evacuate. In the last stages of the effort, Tennant roamed the beaches with a megaphone, calling out, “Is anyone there?” It was Tennant who sent the message to Vice-Admiral Bertram Ramsay just before midnight on the night of June 2: “BEF evacuated.” Four years after Dunkirk, he played a crucial role in the invasion of Normandy and oversaw the installation of two prefabricated “harbors” that were transported across the English Channel in pieces and assembled on Omaha and Gold beaches. In Tennant’s later naval career as an admiral, many sailors continued to call him by the nickname “Dunkirk Joe” in honor of his skill on the beaches.

INSTRUMENTS OF WAR

The Little Ships

LIVING LEGENDS The English regularly commemorate Dunkirk with events featuring boats that participated in the evacuations. Many carry a simple bronze plaque noting their involvement. In 2012, the flotilla of “little ships” above took part in the celebrations marking the 60th anniversary of Queen Elizabeth’s ascension to the throne.

WITH INCREASING numbers of ships needed to ferry soldiers from the beaches of Dunkirk to the large transports waiting in the deeper waters offshore, the British Ministry of Shipping turned to the English people for help. They had at their disposal a database of boat owners that the Admiralty began compiling in mid May, and started making calls and radio broadcasts to shipbuilders and owners along the English coast. The request was straightforward: they needed to collect any boat able to navigate the shallow waters near the Dunkirk shore. Given the dire need, some boats, summarily emptied of all contents, were taken without their owners’ permission and set on course for Dunkirk. By May 30, a collection of 700 pleasure craft, passenger ferries, speedboats, seaplane tenders, private yachts, fishing boats, trawlers and lifeboats were assisting in the operation. And while it is true, contrary to popular legend, that British naval personnel piloted the large majority of the so-called “little ships,” there were also several owners, particularly seasoned fishermen, who made the crossing themselves. By the end of the evacuation, nearly 100,000 soldiers had been rescued with the help of this motley fleet.

In 1940, these little ships were towed down the Thames on their way to their critical service at Dunkirk.

Operation Dynamo: The Final Hours

Nazi bombing raids continued, even as the last soldiers were ferried onto boats. But by June 4, nearly 340,000 troops had been rescued

Lord Gort wanted to remain in Dunkirk until the last of the BEF had been evacuated, but Churchill, concerned that his loss or capture would damage British morale, ordered the leader home on the 31st. Alan Brooke, commander of the BEF’s II Corps who established a corridor for retreating troops and defended the perimeter, was recalled on the 30th. Known for his British reserve, Brooke wept openly while saying his farewells in the sand dunes.

Saturday, June 1, was particularly difficult. For only the second time during the evacuation, the skies cleared for the entire day, allowing the Luftwaffe to pummel the British. At 8:15 a.m., nine Stukas attacked and sank the destroyer Basilisk. Dive-bombers also demolished the destroyer Keith during the morning hours. In the afternoon, a troop transport, the Scotia, with 200 to 300 French soldiers aboard, and a mine sweeper, the Brighton Queen, were both destroyed. In all, nearly a thousand seamen and soldiers were killed and the Luftwaffe exploded 13 British warships, as well as a handful of smaller ships.

With good weather forecast for the next several days, Tennant shifted to nighttime operations and on Saturday, Sunday and Monday evenings evacuated an additional 80,000 men. The final BEF troops left Dunkirk on Sunday night/Monday morning. At dawn on Tuesday, June 4, the 21-year-old destroyer Shikari, filled with French soldiers, made the last departure from Dunkirk. At 9 a.m., French General Maurice Beaufrère, whose 68th Infantry Division had resisted the German advance on the western perimeter, surrendered. Operation Dynamo was over. About 40,000 French troops were captured and the British loss of matériel was significant: six destroyers and more than 240 other marine vessels; almost 64,000 vehicles, including nearly all 445 British tanks; and more than 900 aircraft.

But nearly 340,000 soldiers, including 114,000 Frenchmen, had been rescued and would be available for the fight to come.

FIGHT IN THE AIR The German Stukas (above) with a pilot and rear gunner, were more effective than the British Fairey Battle bombers (on the following page), with their crew of pilot, gunner and navigator.

SELF-RELIANT Some soldiers able to swim out to the destroyers on their own ventured into the deeper harbor waters.

STREAMLINING At first, men waded into water up to their necks to reach rescue boats. But then, the BEF fashioned abandoned vehicles into docks (above and on the following page) and reaching the vessels became easier. Still, more than twice as many men were evacuated from the jetty known as the East Mole as from the beaches.

The View Then

On Monday, June 17, 1940, Time published this measured account of the events at Dunkirk

LOOKING SEAWARD Six days before Winston Churchill became prime minister, he was aboard a destroyer that played a key role in the British evacuation. The issue of Time that included the story reprinted here carried a cover featuring, left to right, French General Maxime Weygand, Paul Baudoin, Prime Minister Paul Reynaud and Philippe Pétain, who later negotiated the armistice that turned his nation over to Hitler.

Great Britain’s eloquent Prime Minister Winston Churchill, last week in a fighting speech to Parliament, admitted British losses of “over 30,000” men killed, wounded & missing, nearly 1,000 guns “and all our transport and all the armored vehicles that were with the Army of the North.” But he said that the Royal Navy, “using nearly 1,000 ships of all kinds, carried over 335,000 men, French and British, from the jaws of death.”

He concluded: “We shall not flag nor fail. We shall go on to the end. We shall fight in France and on the seas and oceans; we shall fight with growing confidence and growing strength in the air . . .”

But last week was certainly not the Allies’ hour. Though two French divisions and one British fought bravely to the end at Dunkirk, and Vice Admiral Jean Marie Charles Abrial of the French Navy jauntily puffed his pipe and stayed ashore until the last launch, the hour was Adolf Hitler’s and he made the most of it.

He had himself photographed in front of the majestic Canadian War Memorial at Vimy Ridge, thus proving that his bombers had not wrecked it. And from his headquarters issued triumphant messages to his soldiers and his people.

EXCERPTS:

“The greatest military achievement of all times was accomplished when Germany, after a surprisingly short time [eleven days], was able to establish main battle fronts along the Rivers Aisne and Somme . . .

“This unprecedented German achievement constitutes simultaneously the greatest military defeat that any military forces ever suffered. A great many lives may have been saved by the British naval forces, but the booty captured is so enormous that no estimate can yet be given . . .”

The German High Command claimed 1,200,000 French, English, Belgian and Dutch casualties and prisoners. It claimed seizing or destroying weapons and matériel for 75 divisions. It claimed destruction of 3,500 enemy airplanes, sinking of 24 warships and 66 transports, damages to 59 warships, 117 transports.

From May 10 to June 1, German casualties were set by the Germans at the fantastically low figure of 10,255 officers and men killed, 8,643 missing, 42,523 wounded. Germany’s admitted airplane losses: 432.

To celebrate his victory, Fuhrer Hitler ordered flags flown throughout Germany for eight days, bells rung for three. As his war machine swung from Flanders into action on the Somme-Aisne line, he declared :

“Inasmuch as the enemy still spurns peace, the fight will be carried on to his total destruction.”

U. S. correspondents who were taken along by the Germans in their pursuit of the Allies to the sea repeatedly expressed amazement at the Hitler machine’s fitness and efficiency. They saw windrows of Allied but few German corpses, the German system being to bury their dead within an hour for reasons of morale as well as hygiene. Even before Dunkirk’s final fall, masses of German troops began moving to the new southern front. German mechanics drove back long lines of abandoned Allied motor trucks, camouflaging them with their own blue-grey paint, loading them with salvaged parts such as batteries, tires, spark plugs or with captured gasoline and other supplies. German engineers were already at work reconditioning the captured Channel ports (but the British, after two tries, effectively blocked Zeebrugge with four ships full of concrete).

Reported by U. S. correspondents were some fine points of Nazi technique:

• In bombing enemy columns, German pilots aimed their missiles at the roadsides, whence their fragmentation was just as devastating, rather than blowing holes in the road surface, which might impede pursuing German columns. Similarly, in razed towns, whole blocks of houses were destroyed without damage to the streets.

• Cultivated fields, in which harvests will soon be ripe for the German conquerors, were virtually unscathed by bombing or artillery fire.

• German officers called the stench of death “the perfume of battle.”

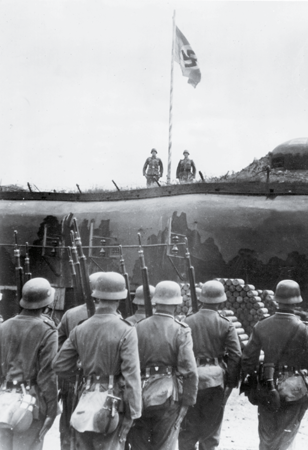

TO THE VICTORS Hitler’s troops raised the Nazi flag (above) over the Maginot Line—pride of the French military—three months after German forces marched into Dunkirk (on the following page) on June 5, 1940.

WELCOME HOME Returning soldiers were embraced as heroes. While most were transported from Dunkirk to Dover, several other English ports were used as well, including Folkestone, Ramsgate, Margate and Newhaven.