10

10

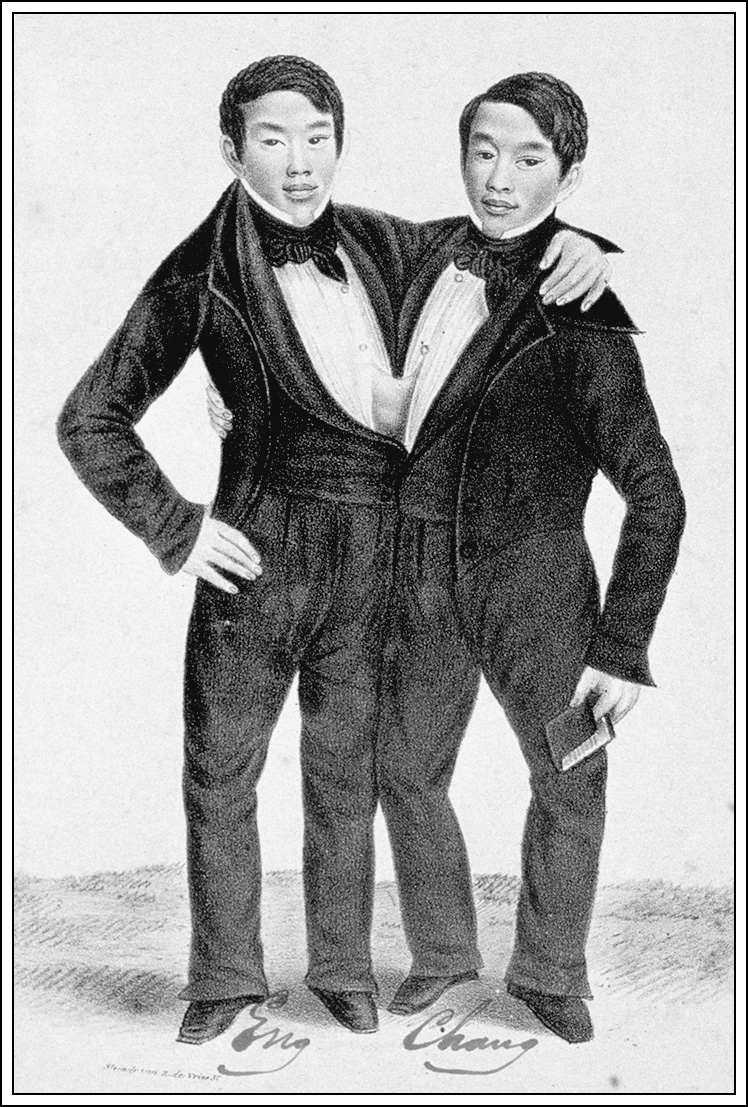

CHANG AND ENG, LITHOGRAPH (1830)

“Southern Asia, in general, is the seat of awful images and associations,” Thomas de Quincey declared in his Confessions of an English Opium-Eater (1822), and he soon expanded that geography to include the entire continent of Asia, or wherever the mighty British Empire had flexed its colonial muscles in that part of the world. A prose master and inveterate opium addict, de Quincey was haunted by his exotic hallucinations—drug-induced nightmares in which he was surrounded by monstrous creatures, tortured by outlandish imageries: “I was stared at, hooted at, grinned at, chattered at, by monkeys, by paroquets, by cockatoos. I ran into pagodas: and was fixed, for centuries, at the summit, or in secret rooms. . . . I was kissed, with cancerous kisses, by crocodiles; and laid, confounded with all unutterable slimy things, amongst reeds and Nilotic mud.” Like a ghost traveling in endless catacombs, he occasionally managed to escape, but then he found it was merely to transition to a different, but equally horrific, dream scene: “I escaped sometimes, and found myself in Chinese houses, with cane tables, &c. All the feet of the tables, sophas, &c. soon became instinct with life: the abominable head of the crocodile, and his leering eyes, looking out at me, multiplied into a thousand repetitions: and I stood loathing and fascinated.”1

Unlike his predecessor Samuel Coleridge, whose opiate-induced reverie took him on an exhilarating time travel to Kublai Khan’s Xanadu, de Quincey seemed to be cursed with sinister nightmares, an existential dilemma he blamed on a roaming Malay who had once knocked on his cottage door. A few years earlier, de Quincey claimed, a turbaned, “ferocious looking” Malay man happened by his mountain cottage, gesticulating in a foreign tongue, failing to communicate anything sensible to the baffled British writer. Like that fated knock at the gate in Macbeth, which de Quincey masterfully interpreted in an essay widely regarded as the paragon of English prose, the chance encounter with the mysterious Malay ushered in an unstoppable torrent of bad dreams: “The Malay has been a fearful enemy for months. I have been every night, through his means, transported into Asiatic scenes.”2

Even a run-of-the-mill literary critic with rudimentary knowledge of cultural psychology can see through the smoke screen put up by de Quincey here. He called Asia, where the British Empire had been inexorably expanding, the “great officina gentium” (workshop of people). It is, as he put it, “the part of the earth most swarming with human life,” a jungle where “man is a weed.”3 In other words, de Quincey’s nightmare was really a symptom of the British guilt over colonial conquest of Asia, an expression of a collective unconscious torn between arrogance and fear, fascination and revulsion. Later, de Quincey would lose his son Horace in the First Opium War with China (1839–42), consequently turning the former guilt-ridden opium-eater into a most vocal, saber-rattling cheerleader for the opium trade and British pride. For now, however, de Quincey’s candid confession, that he “stood loathing and fascinated,” not only was a self-description but also aptly captured the British sentiment toward the exotic land of Asia, which now sent a representative not in the form of de Quincey’s quaint, turbaned Malay, but rather the conjoined Siamese Twins.

After a whirlwind of successful and profitable debuts in major northeastern cities, Captain Abel Coffin and Robert Hunter decided to take the twins to the British Isles and Europe. On October 17, 1829, they boarded the packet ship Robert Edwards, bound from New York Harbor for England. Before their departure—perhaps minding Dr. Warren’s warning about the potential early demise of the twins in a new climate and environment—Coffin took out a $10,000 life-insurance policy on his prized curiosity to cover any possible loss as well as the costs of shipping the bodies, should they die aboard, to the port of destination. He also packed for the journey an ample supply of embalming materials: molasses and corrosive sublimate (mercuric chloride). Live or dead, the twins would make money for their owners. In the long history of displaying human oddities, dead bodies were often just as lucrative for impresarios as live ones. As Susan Stewart puts it in her profound meditation on the abnormal, for curiosity seekers, “it does not matter whether the freak is alive or dead.”4 In Philadelphia, Charles Peale was known for staging spectacles of death at his museum. Just a few years down the road, P. T. Barnum would turn the corpse of Joice Heth, allegedly a 161-year-old slave and former nurse of baby George Washington, into an exhibition as profitable as when the woman was still alive.

Comforted by the large sum of insurance, and by the knowledge that even dead twins would be a cash cow, Coffin went ahead and did something that would plant a seed of resentment in the twins’ mind. For the journey to England, Coffin had booked first-class tickets for himself, his wife Susan, and manager James Hale, while the twins and their companion Tieu had to travel in steerage. As the twins recalled later, while the first-class passengers wined and dined on fresh luxuries, Chang and Eng had to stay in cramped quarters and to “set down day after day to eat salt beef and potatoes.” To make matters worse, when they protested the glaringly unfair treatment, Coffin blamed it on the ship captain, claiming that first-class tickets had been purchased for the twins but the cabins were overbooked. But the fact is, as the twins would later find out and describe angrily in a letter, Coffin had “screwed a hard bargain for our passage to England, in the steerage of the ship and having us under the denomination of his servants—all for the paltry savings of $100 and yet wishing to keep us in good temper and wishing moreover to make us believe that he spared no expense for our comfort.”5 Regarded as freaks, the twins would always have to fight to be treated as humans. The battle had merely begun, and the odds were against them, as England awaited their arrival.

After a month of rough autumn sailing across the icy-cold Atlantic, the Robert Edwards docked in Southampton on November 19, 1829. The twins were immediately taken to London, where Coffin had reserved rooms at the North and South American Coffee House on Threadneedle Street. Adjacent to the commercial epicenter of the Royal Exchange, the inn was a popular spot for ship captains and business representatives of American and European firms, who could get access there to American newspapers and obtain information about “the arrival and departure of the fleet of steamers, packets, and masters engaged in the commerce of America.”6

As it happened, 1829 was the penultimate year of the reign of the ailing King George IV. Soon assuming the title of “the empire on which the sun never sets,” Great Britain was on the verge of a spectacular ascent as a global power. Having defeated Napoleon in the previous decade, Britain saw its Royal Navy rule supreme in all parts of the world. When the Caribbean sugar economy declined due to competition and the abhorrence of goods derived from slave labor, the focus of the British colonial interest shifted to Asia, with the East India Company fast expanding its reach in India and China. The Industrial Revolution gave Britain the technological advantage over these Asian countries mired in millennia-old feudalism. In Siam, the 1826 Burney Treaty had given the British a colonial foothold. Domestically, the year 1829 also saw the passage of the Roman Catholic Relief Act, which for the first time allowed Catholic MPs to sit in Parliament. And after Parliament passed the Metropolitan Police Act, sponsored by Sir Robert Peel, the first thousand police officers, dressed in blue tailcoats and top hats, began to patrol the streets of London on September 29. These sartorially enhanced police were first nicknamed “Peelers,” and then dubbed “Bobbies,” both in honor of the minister who had pushed the bill through Parliament.

Arriving in London, then housing a staggering population of more than one and a half million, the twins were impressed not only by the newly minted Peelers on foot patrol, but also by the dense fog that had historically given the city its unique reputation. Ever since the eighteenth century, the smoke and soot from coal burning in the full-throttled engines of the Industrial Revolution led to a climatic menace. On long winter days, yellow, sulfurous smog blanketed the city and blocked the sun. In the famous opening of Bleak House (1853), Charles Dickens gave us a vivid description of how his native city suffered in the hoary grip of the demonic veil: “Fog everywhere. . . . Fog in the eyes and throats of ancient Greenwich pensioners, wheezing by the firesides of their wards; fog in the stem and bowl of the afternoon pipe of the wrathful skipper, down in his close cabin; fog cruelly pinching the toes and fingers of his shivering little ’prentice boy on deck. Chance people on the bridges peeping over the parapets into a nether sky of fog, with fog all ’round them, as if they were up in a balloon, and hanging in the misty clouds.”7

On the day of the twins’ arrival, The Times reported that what Dickens called a nether sky of fog had covered the metropolis and its vicinity: “In Westminster-road, at 11 o’clock in the morning, the opposite side was not visible. At 12 o’clock you could discern objects at a distance of 300 yards, and this continued for an hour or more, but at the same time the neighborhood of the Royal Exchange was nearly in midnight gloom.”8 Inured to the natural surroundings of a Siamese river town, Chang and Eng at first did not know what to make of the strange sights of a densely populated city rendered ghostly by smog. According to James Hale, “the day after their arrival there, it being necessary to have lighted candles in the drawing room at noon, in consequence of the fog and smoke, they went to bed, insisting that it was not possible it could be day-time.” Moreover, the damp weather did not agree with the twins, who both immediately fell ill, suffering from colds and coughs. Despite their discomfort, these young fellows tried to keep up their spirits through wisecracking, a character trait that would stand them in good stead on and off stage. Taking a deadened coal from the grate and holding it up, they called it “the London sun.” Seeing snowfall for the first time in their lives, they asked, perhaps mockingly, “whether it was sugar or salt.”9

The reporters invited by Coffin for a sneak preview were smitten with what they saw. Their published reports soon filled the pages of newspapers distributed all over the British Isles. A lengthy article in the Times described the physical features of these wonder boys, playing up on the theme that the twins were at once strikingly normal, just like each one of us, and freakishly abnormal:

They are two distinct and perfect youths, about 18 years of age, possessing all the faculties and powers usually possessed at that period of life, united together by a short band at the pit of the stomach. . . . Their arms and legs are perfectly free to move. . . . In their ordinary motions they resemble two persons waltzing more than anything else we know of. In a room they seem to roll about, as it were, but when they walk to any distance, they proceed straight forward with a gait like other people. As they rose up or sat down, or stooped, their movements reminded us occasionally of two playful kittens with their legs round each other; they were, though strange, not ungraceful, and without the appearance of constraint and irksomeness.

The reporters drew attention to the twins’ racial, or specifically Chinese, features, at a time when Chinese were still a rare sight in London. This was still a few decades before a large influx of Chinese immigrants would turn a part of the East End into the infamous Limehouse District, depicted in popular literature as a warren of opium dens, gambling parlors, and brothels:

In the colour of their skins, in the form of the nose, lips, and eyes, they resemble the Chinese, whom our readers may probably have seen occasionally about the streets of London, but they have not that broad and flat face which is characteristic of the Mongol race. Their foreheads are higher and narrower than those of the majority of their countrymen. The expression of their countenance is cheerful and pleasing rather than otherwise, and they seem much delighted with any attention paid to them.

In conclusion, the reporters reiterated their opening thesis, tantalizing the readers with a promise of wonder without impropriety: “Without being in the least disgusting or unpleasant, like almost all monstrosities, these youths are certainly one of the most extraordinary freaks of nature that has ever been witnessed.”10

On November 24, after the twins had recovered, a private viewing party was held at the Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly, setting the stage for the public exhibition later. As in all previous previews in American cities, Coffin and Hunter, the proud co-owners, invited a most distinguished group of doctors and other social elites to this event. The guests were a roll call of the upper echelons of London in the fields of medicine, science, and politics: Leigh Thomas, president of the Royal College of Surgeons; Sir Astley Cooper, indisputably the most eminent surgeon and anatomist of the time and an authority on vascular surgery; Sir Benjamin Collins Brodie, a physiologist and surgeon who pioneered research into bone and joint disease and to whom Henry Gray would dedicate his famous book Gray’s Anatomy in 1858; Sir Charles Locock, an obstetrician to the future Queen Victoria; William Reid Clanny, doctor and inventor of the safety lamp for coal mines; Henry Halford, physician extraordinary to King George III; George Birkbeck, doctor, academic, and philanthropist, who founded Birkbeck College (now part of the University of London); John Harrison Curtis, aurist (otologist) who treated deafness and wrote the most authoritative book in the field, A Treatise on the Physiology and Diseases of the Ear (1817); and other distinguished guests.

Equally as prominent as the guests was the venue chosen for this soirée. Situated in the heart of Piccadilly, the Egyptian Hall had an imposing façade resembling the ancient Temple of Tentyra (Dendera). It was founded in 1812 by William Bullock, a Pickwickian entrepreneur, showman, naturalist, antiquarian, silversmith, jeweler, taxidermist, botanist, zoologist, and traveler. The museum housed Bullock’s vast collection of artifacts, ranging from curiosities brought back from the South Seas by Captain Cook to Napoleon’s carriage captured at Waterloo. In 1824, Bullock had staged Britain’s first exhibition of Mexican artifacts and natural fauna—a show that featured stone and pottery figures, indigenous deities, a jade Quetzalcóatl, an obsidian mirror, an Aztec calendar stone, forty-three glass cases of flora and fruits (melon, avocado, tomato, banana, breadfruit, prickly pear, etc.), and exotic birds, such as flamingos and hummingbirds.11 In fact, the Egyptian Hall had played such an important part in seizing and inspiring the British colonial imagination about the world that Dickens, as the most studious chronicler of London, would one day immortalize the venue in his oeuvre.12 In 1829, however, seventeen-year-old Dickens had just learned shorthand and was walking the foggy city streets as a freelance journalist. And Bullock had already auctioned off his prize collections, sold the museum to his nephew George Lackington, and left for Mexico in the midst of a British frenzy of investing in Mexican silver mines.

On the bone-chilling evening of November 24, as Piccadilly’s cobblestoned street became a canal of thick fog and the gas lamps blinked their ghostly yellow eyes, the distinguished guests arrived one after another in crested carriages for the private levée. The twins, dressed in short green jackets and loose pantaloons, their long queues wrapped around their heads, made themselves presentable to the bigwigs garbed in swallow-tailed suits and bowties. As much as they would have liked to waltz freely across the ballroom, the way they used to swim in the Meklong, Chang and Eng had become more like caged animals—one of the many on the long list of curiosities that had or would come before this elite crowd, to be inspected, poked, tested, and, most important of all, verified. As the lead surgeon, Sir Astley was the first to approach the singular spectacle. After examining the band, its dimensions and appearance, Astley pronounced it “to be cartilaginous and not cutaneous only.” His opinion was confirmed by the other doctors who took turns feeling the band. Although earlier in Boston, Dr. Warren had already made the discovery, the British physicians were astonished to find that the twins had but one navel, situated at the center of the connecting band, thus rendering the proverbial term navel gazing kind of moot. It was a parlor joke that would not be lost among the distinguished crowd steeped in wry British humor.13

Before the evening was over, thirty-four guests signed a statement testifying, as only the English could, to both the authenticity of the unusual union and the appropriateness of a public exhibition. “The public may be assured,” the statement read, “that the projected exhibition of these remarkable and interesting youths is in no respect deceptive; and further that there is nothing whatever, offensive to delicacy in the said exhibition.” As if one certificate were not enough, Dr. Joshua Brooks, an anatomist, drafted and signed a separate testimonial: “Having seen and examined the two Siamese Youths, Chang and Eng, I have great pleasure in affirming they constitute a most extraordinary Lusus Naturae, the first instance I have ever seen of a living double child; they being totally devoid of deception, afford a very interesting spectacle, and they are highly deserved of public patronage.”14

Both certificates would be reproduced verbatim in the promotional pamphlet for sale at future exhibitions of the twins, according the conjoined bodies an indisputable legitimacy and increasing their cultural capital in the eyes of the viewing public. Soon these “Siamese Youths” were the talk of the town in London and, in fact, the entire British Isles.