29

29

After a rather humiliating stint at Barnum’s American Museum in New York, Chang and Eng struck out again on their own. Considering themselves gentry, they no longer wanted to be dime-museum freaks or sideshow riffraff. So in November 1860, when the nation was roiling as a result of the presidential election, the twins took two of their children, Montgomery and Patrick, and boarded a ship for California.

Judging by their latest two attempts, Chang and Eng astutely concluded that the East Coast market had been tapped out and that the fast-growing West, to which people continued to flock, might present better opportunities. Since the discovery of gold twelve years earlier, California had boomed. San Francisco, initially a loose cluster of adobe haciendas, had mushroomed into a city overnight; or, as Will Rogers quipped, it “was never a town.” But getting to the fabled Gold Mountain before the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869 or the Panama Canal in 1914 required a lengthy journey. From New York, the twins and their sons sailed for eight days down to Panama City, and then took a train across the Isthmus of Panama to catch the steamship Uncle Sam on the other side.

Aboard the 1,800-ton Pacific Mail steamer, the Bunker quartet sailed for the new Eldorado. During the sixteen-day journey, they saw, as teenage Montgomery wrote in a family letter, plenty of whales and flying fish, and enjoyed a diet of fresh green corn, beans, and peas. When the ship stopped at Acapulco, Mexico, for coal, the ubiquitous palm trees and the verdant tropical vistas caused a stir in the twins’ hearts, a sudden pang of homesickness—not for North Carolina but for Siam, which lay far beyond the horizon of the blue Pacific, the “heart-beating center of the world,” as Melville put it. Among the passengers was a Reverend J. A. Benton, native of Sacramento, who had left California for China a year and a half earlier on a mission to demonstrate that, “if one will but keep going in the same direction he will get home again at last.” Speaking at length with the globetrotting reverend, the twins were hungry for any tiny morsel of tidings about the native land they had left almost a lifetime earlier.1

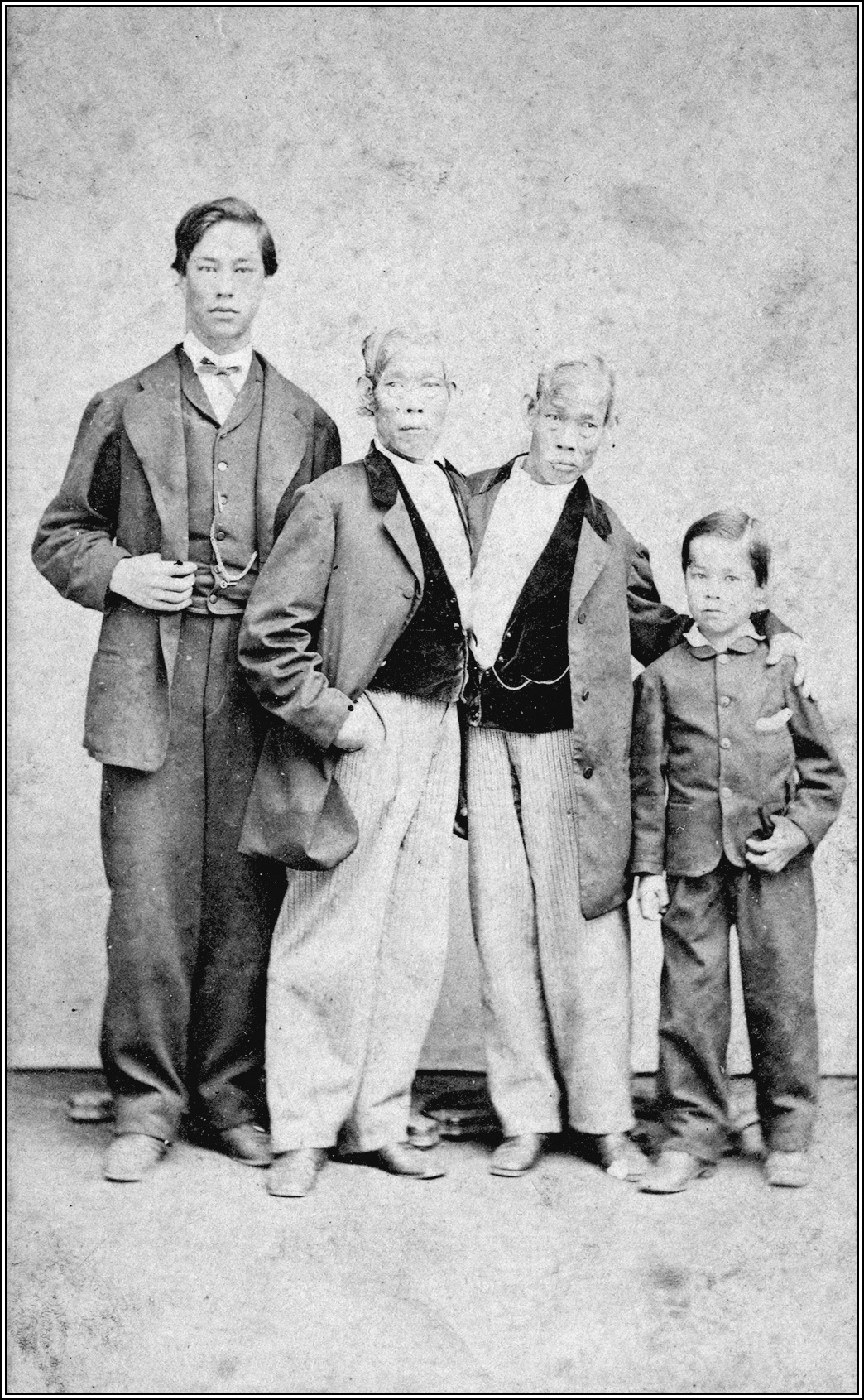

CHANG AND ENG BUNKER AND THEIR CHILDREN

Arriving in San Francisco, Chang and Eng were surprised to find that their reputation had preceded them. Not only were they household names, but their success as showmen had also spawned imitation and mockery in the hands of a new breed of performers, who represented an emerging American art: the minstrel show. In fact, when they were still in New York, they had already witnessed the increasing popularity of blackface minstrelsy. During the month of their exhibition at the American Museum, at least half a dozen minstrel bands were performing every night at popular local joints, including Niblo’s Saloon, Mechanics Hall, and the New Bowery Theatre.

Minstrelsy had begun in the early 1800s with white men in blackface portraying Negro characters and performing putative Negro songs and dances. By the mid-nineteenth century, it had expanded its repertoire, or racial cast, to include Chinese, Irish, Japanese, Native American, and other ethnic minority characters. Originating in East Coast cities, minstrelsy had also spread geographically, especially to California. According to Robert C. Toll, “When a large number of people trekked across the continent in search of California gold . . . minstrelsy quickly established itself there. First presented in 1849 by local amateur groups scattered throughout the goldfields, minstrelsy by 1855 claimed five professional troupes in San Francisco alone.”2 A sure sign that San Francisco had become a hub for minstrelsy, one of the most famous troupes at the time, the Christie Minstrels, led by E. P. Christie and others, “changed their name to Christie’s San Francisco Minstrels to add to their luster when traveling around the country.”3

What made California a particularly fertile ground for minstrelsy was not only the prevalence of rowdy, gun-toting, pleasure-seeking crowds but also the huge influx of immigrants who made for a more racially mixed population. The Chinese, especially, had a strong presence in California, a fact repugnant to many and one that, as we saw, had irked the ilk of Hinton Helper, Chang and Eng’s fellow Tar Heeler-turned-Sinophobe. Chinese immigration to the United States had been sporadic before the mid-nineteenth century, but the discovery of gold at John Sutter’s mill suddenly spiked the number of Chinese arriving in North America: 325 in 1849, 450 more in 1850, 2,716 in 1851, and 20,026 in 1852. By 1860, there were about 37,000 Chinese in the United States, most in California. At first, Chinese were welcomed in the state that had just joined the Union in 1850. Their arrivals were routinely reported in the newspapers as increases to a “worthy integer of population.” But as the competition in the goldfields became more intense, the tide soon turned against the Chinese, and the affectionate feelings soured. When Emerson said in 1854, “The disgust of California has not been able to drive or kick the Chinaman back to his home,” the New England sage seemed well informed about the happenings in the Wild West and the rise of anti-Chinese sentiments, which would soon lead to mob violence and the passage of discriminatory laws. A sure sign of change in the air: The word Chinaman, previously a neutral, catchall term for Asian men, had already picked up a negative tone when Emerson used it.4

Rising hostility toward the Chinese led to demeaning portrayals in minstrel shows. The stock character of John Chinaman—in yellowface, sporting a long queue and a pair of loose pantaloons, speaking in a caricatured dialect—often appeared on the minstrel stage, as depicted in the following song, “Big Long John”:

Big Long John was a Chinaman,

and he lived in the land of the free . . .

He wore a long tail from the top of his head

Which hung way down to his heels . . .

He went to San Francisco for Chinee gal to see,

Feeling tired, he laid down to rest,

Beneath the shade of huckleberry tree.

Or, as in another minstrel song, “Hong Kong,” in which John Chinaman speaks of his doomed love for his “lillee gal”:

Me stopee long me lillee gal nicee

Wellee happee Chinaman, me no care,

Me smokee, smokee, lillie gal talkee,

Chinaman and lillee gal wellee jollee pair.5

As a predecessor to Ah Sin, the other stock character created and popularized by F. Bret Harte in his satirical poem “The Heathen Chinee,” John Chinaman was the Asian counterpart to such blackface figures as Jim Crow and Zip Coon. During his disappointing adventure in the West, Hinton Helper must have been so impressed by these minstrel songs that he would later adopt “John Chinaman” as the generic name for all the “Celestials” maligned in his books.

Arguably the most famous “Chinamen” in the nineteenth century, the Siamese Twins naturally were featured in minstrel shows that parodied the Chinese. Their nonstop tour across the country from 1829 to 1839, followed by sensational stories of their married lives in the South, had turned them into cultural icons as familiar as Charlie Chan and Fu Manchu were in the twentieth century. In Orientals: Asian Americans in Popular Culture, a study of the representation of Asians in American culture, Robert G. Lee astutely identifies two motifs of change embodied by the Siamese Twins: “The forty-year career of Chang and Eng suggests both the shift in the signification of the Chinese from object of curiosity to symbol of racial crisis and the shift in the popular sites of that signification from museum to minstrel show.”6 In other words, if a freak show, as I have suggested earlier, often staged racial freaks, the rise of minstrelsy in the 1840s and the surge of anti-Chinese sentiments in the 1850s had opened up a new arena for the staging of racial others. Freak show was transitioning to minstrel show, or at least the two were joining forces to channel the boiling racial tensions in antebellum America. It was a historical change experienced, and indeed embodied, by Chang and Eng.

On December 10, 1860, when the twins opened their exhibition at Platt’s New Music Hall in San Francisco, many in the audience had already seen or would soon see minstrel renditions of the freak show. Chief among those minstrel appropriations were the skits performed by Charley Fox and Frank B. Converse, both pioneers of blackface minstrelsy. Fox was known for the popular songbooks he edited, and Converse was regarded as the “Father of Banjo.” As seen in a songster cover, the Fox–Converse team performed banjo duets by impersonating the Siamese Twins, tossing their pigtails and kicking around the stage with pointed wooden shoes. Chang and Eng’s unique physicality, something that the twins themselves had exploited successfully in their onstage repartee, also made it convenient for Fox and Converse to appropriate the twins as characters for skits such as “Conundrums,” which featured chin-wags between two speakers:

When is a bedstead not a bedstead?

When it’s a little buggy.

Why is a railroad-car like a bed-bug?

Because it runs on sleepers.

Why is a poor man like a baker?

Because he needs de dough.

Who was the oldest woman?

Aunt-Iniquity.7

Arriving in the West after the Civil War broke out, hence too late to see Chang and Eng’s California shows in person, Mark Twain nonetheless had an obsession with the Siamese Twins that was part of his lifelong infatuation with what he called the “genuine nigger show.” Twain, or little Sam, first saw minstrel shows when he was growing up in Hannibal, Missouri. He was struck by the “loud and extravagant burlesque.”8 Like Jakie Rabinowitz, the boy who fell in love with “negro numbers” (jazz songs) against his Orthodox Jewish father’s strictures in the iconic film The Jazz Singer (1927), Twain became enamored with minstrelsy despite his mother’s warnings. After he arrived in the West, he regularly attended performances of the San Francisco Minstrels, whose core members included Billy Birch, Dave Wambold, and Charley Backus. In his Autobiography, Twain devoted an entire chapter to minstrelsy, detailing his childhood fascination with it, his later acquaintance and friendship with blackface artists, and his lament over the passing of the golden age of minstrelsy, declaring that, “if I could have the nigger show back again in its pristine purity and perfection I should have but little further use for opera.”9 As for Twain’s literary work, there has been ample scholarship shedding light on the fact that Twain, very much like Melville and other major American writers of that era, was indebted to blackface minstrelsy both aesthetically and ideologically. Critics have noted how, for instance, in both Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and Tom Sawyer Abroad, Twain appropriated the three-part structure of a minstrel show as a controlling framework for narrative; or how he lifted many of his most radical elements from minstrelsy when he absorbed its costuming, vernacular, and stock figures; or how he learned beneficially from minstrelsy “its insistence on a self that was complexly constituted from a mixed gender, class, and racial sourcepool.”10 Ralph Ellison’s astute remark that Nigger Jim in Huckleberry Finn rarely emerges from behind the minstrel mask also speaks to blackface’s profound influence on Twain’s literary imagination.11

Scholars have also noticed that Twain carried his avowed love for blackface minstrelsy into his obsession with the Siamese Twins. Around 1868, he wrote the burlesque sketch “Personal Habits of the Siamese Twins,” which traffics more in exaggeration than fact. The beginning of the story resembles closely the standard opening of a minstrel routine called a “stump speech,” which always starts with a personal pitch to gain the audience’s confidence: “I do not wish to write of the personal habits of these strange creatures solely, but also of certain curious details of various kinds concerning them, which, belonging only to their private life, have never crept into print. Knowing the twins intimately, I feel that I am peculiarly well qualified for the task I have taken upon myself.” After plenty of absurdities, the piece ends with an obviously facetious factoid: “Having forgotten to mention it sooner, I will remark in conclusion that the ages of the Siamese Twins are respectively fifty-one and fifty-three years.”12 And then there was the book known as The Tragedy of Pudd’nhead Wilson, to which is attached, like Siamese Twins, a sequel called The Comedy, Those Extraordinary Twins. Twain himself admits candidly to the defect of his creation: “two stories in one, a farce and a tragedy.” Even though Pudd’nhead Wilson is allegedly based on a different set of Siamese Twins, Twain worked some of Chang and Eng’s life stories into the novel, full of burlesque and other features of blackface minstrelsy: disguises, cross-dressing, racial mixing, and pastiche.13

The epitome of Twain’s appropriation of the Siamese Twins as minstrel figures, however, was his stage performance. A successful public speaker who made almost as much money from lectures as from book royalties, Twain often tapped the repertoire of minstrelsy in his delivery of speeches, casually reeling off anecdotes, scrapping rhetorical flourishes, and shooting for foolery and the tall tale. The famous tagline for his lectures, “The Trouble Begins at Eight,” was actually a standard byline in minstrel-show advertisements.14 On February 28, 1889, when storyteller James Riley and humorist Edgar “Bill” Nye gave a program of readings at Tremont Temple in Boston, their manager induced Twain on short notice to introduce the duo. His unexpected appearance on the stage “provoked a great waving of handkerchiefs and a tumult of applause and cheering, the organist doing his bit by sounding off fortissimo.” Not missing a beat, Twain stepped into the spotlight and introduced Riley and Nye as Chang and Eng. His opening salvo ripped a page from his own earlier sketch of the famous twins, establishing his own credibility as the speaker while making the audience chuckle and roar: “I saw them first, a great many years ago, when Barnum had them, and they were just fresh from Siam. The ligature was their best bond then, but literature became their best hold later, when one of them committed an indiscretion, and they had to cut the old bond to accommodate the sheriff.”15

As if turning others into the Siamese Twins were not enough, Twain would eventually act in character himself. On December 31, 1906, more than twenty years after the deaths of Chang and Eng, Twain put on a Siamese Twins performance with the aid of a young man at a New Year’s Eve dinner party on New York’s Fifth Avenue. Both dressed in white and tied together by a pink sash, which stood for the connecting band, the pair had their arms around each other. Harking back to teetotaler Eng in “Personal Habits” and upright Angelo in Pudd’nhead Wilson, Twain’s character pleaded the temperance cause while his twin brother kept nipping from a flask:

We come from afar. We come from very far; very far, indeed—as far as New Jersey. We are the Siamese Twins. . . . We are so much to each other, my brother and I, that what I eat nourishes him and what he drinks—ahem!—nourishes me. . . . I am sorry to say that he is a confirmed consumer of liquor—liquor, that awful, awful curse—while I, from principle, and also from the fact that I don’t like the taste, never touch a drop.

As he continued to stump for reform and his twin continued to nip, the alcohol apparently influenced both. The two began to stagger around the stage, the speech slowly becoming a slurring jumble:

Wonder’l ’form we are ’gaged in. Glorious work—we doin’ glorious work—glori-o-u-s work. Best work ever done, my brother and work of reform, reform work, glorious work. I don’ feel jus’ right.

According to a report on the front page of the New York Times the next day, Twain’s skit brought down the house so noisily that he could not continue the “lecture.”16 As the telharmonium, an electrical device invented by Thaddeus Cahill that year, transmitted the music of “Auld Lang Syne” from Broadway, the dinner guests and the host bade farewell to another year gone by, a year when Twain famously and openly lamented that the minstrel show had “degenerated into a variety show” and that he missed the good old days of the “real negro show,” days when he was roaming the Wild West, when the tam and bones of Birch, Wambold, and Backus caused uproarious laughter that shook Frisco harder than the big quake that year, and when the real Siamese Twins and their dog-gone “authentic” imitations drew in crowds as thick as flies.

Twain might have been carried away by nostalgia, but it is certainly true that whether appearing as yellowface characters in a minstrel skit or acting in person in a freak show, the Siamese Twins were a big attraction in the West, even in a period when the political crisis leading to the Civil War dominated the news. As the Daily Alta California reported on December 15, 1860, “The interest in these wonders of nature continues unabated.” Or, a week later, when they moved north along the Sacramento River to hit the gold-mine towns newly populated by modern-day Argonauts, the Sacramento Daily Union—which would one day give Twain a head start as a writer—reviewed Chang and Eng’s show on December 22: “The Siamese Twins held their levée at the Forrest Theater yesterday afternoon and evening, and were visited by a large number of citizens. They are introduced to the audience by their agent, who gives a brief sketch of their history, etc.; after which, they mingle with their visitors, conversing freely and pleasantly, in good English.”17

There were also reports that the twins advertised among the Chinese, using Chinese-language flyers to attract the “Celestials” to their exhibition tent.18 We don’t know how successful those efforts were, for the Chinese had been driven out of the minefields by white prospectors. A lethal combination of unfair tax laws targeting the Chinese and anti-Chinese violence had made mining an unfeasible choice of profession for these Chinese immigrants, thus giving birth to a saying that would echo throughout the nineteenth century, “no Chinaman’s chance.” In fact, Twain had gone to California because he had lost his job as a journalist in Nevada after he had expressed sympathy for abused “Chinamen.” Standing no chance in mining, Chinese men, who had never done domestic chores like washing clothes and cooking in their native China (those jobs were for women), opened laundromats and fast-food joints in order to earn a living. As laundrymen toiling away with steam and starch, or as cooks stir-frying endless orders of chop suey, they would have been unlikely attendees at the Siamese Twins’ shows.

Whether or not the twins were able to meet up with local Chinese, they had kept in contact with their families back home in North Carolina and continued to concern themselves with seemingly mundane details of husbandry on their farms. In a rare extant letter penned by the twins themselves, Eng wrote:

Dear wife and children we wanted to know very much how are you coming on. we have not hear from you for 6 weeks. we got two letters from you since we left. i hope you has done hauld the corn from Mr. Whitlock before now Tell Mary to take care of catle & pigs—i wanted to know very much how mill coming on—most likely we will be back in march—maybe not till may or june—you must tell Mary to have every thing carige on wright— leave a truk in n york with Mr. Hale he send it home by way of Marmadow tell Mr. Gilmer if we have any thing to hauld from their to have our truk bring it on too—nothing in them but shoese & coat for Mary—We has not seen much gold yet but hope to get some befor long—i must bring this close—Hope this will fine you all well & happy take good care of the five—write soon to this Place your has ever E.19

Pretty soon they would have more than cattle and pigs to worry about. At the end of 1860 and the beginning of 1861, after the election of Abraham Lincoln, daily headlines in the newspapers portended a national crisis on the horizon. In fact, on the days after the historic election and before the twins had left New York for the West Coast, Chang and Eng had already seen their own names linked in the news to the crisis. While minstrel artists had exploited the twins’ image for entertainment, the raging national debate over the fate of the union had also used the conjoined twins as a most salient and powerful metaphor. As seen in this political burlesque printed in the New York Tribune,

The “Union” in Danger—Chang threatens to secede—There is a report in circulation that a dreadful quarrel took place between the Siamese twins, at the American Museum, on the 7th inst. It seems that Chang, who is a North Carolinian and a secessionist, had insisted upon painting the ligament black which binds them together. To this Eng objected, preferring the natural color; whereupon Chang resolved to “sever the union” with Eng, which he declared to be “no longer worth preserving.” Eng, who is of a calmer temperament, finally persuaded him to wait a little—until the 4th day of March next. Dr. Lincoln, a pupil of the celebrated Jackson, was called in, who gave his opinion that the operation would be dangerous for both parties, and said the union must and shall be preserved. A system of non-intercourse will probably be adopted—each party preserving to himself the privilege of biting his own nose off.20

Alluding to Lincoln’s inauguration on March 4 and his famous speech about the imperative of preserving the union, the newspaper satire made full use of the symbolic valence of the Siamese Twins in American lexicon and cultural lore. In the coming days, as the North and the South veered closer to a calamitous clash, newspapers invoked the conjoined twins again and again as an allegory for the union, as the Baltimore American did in the following verbal skit, likening secession to a supposed separation of Chang and Eng:

If one of the Siamese brothers, disgusted with his life-long contact with the other, rudely tears himself away, snapping asunder a bond that God and nature intended to be perpetual, he inflicts upon himself the same precise injury that he inflicts upon his fellow. Each spouting artery, each quivering muscle, each wounded nerve that he tears in the lacerated side of his discarded companion, has an exact counterpart in his own equally lacerated side. He commits fratricide and suicide at once.21

With a storm brewing, the twins could no longer linger in the West looking for gold. On February 11, 1861, they boarded the steamer Golden Age and started their homecoming journey. Always steadfast in their own bond, Chang and Eng had no idea how strong the state of the national union was, or how the catastrophe would wreak havoc in their conjoined life while also tearing the country apart.