5

5

For the twins, the trip to Bangkok was both eye-opening and remunerative. In addition to selling their duck eggs at the bazaar after the palace visit, they also peddled the king’s gifts as soon as they got back home. Many years later, sitting in the cool breeze of their North Carolina front porch on summer days or by the warm fireplace on winter nights, the twins would often reminisce about that unforgettable trip to the Siamese capital. By then, retired comfortably from the world and seemingly without a thing to worry about, they would express regret about selling those royal gifts for what in retrospect must have been a paltry sum. But the family had needed the money then to survive and to expand their duck and egg business. Like lake water that settles down after a stone skiffs the surface, life soon returned to its peaceful norm for the twins in their small fishing village.

Robert Hunter, however, could not forget the “wonder boys” he had “discovered.” A hardheaded Scotsman, he was not going to give up easily and let Rama III’s refusal stand in the way of his golden dream. Since his arrival in 1824, Hunter had tried, not always successfully, to exert influence on Siamese affairs. Besides his trade partnership with the king and the nobles, Hunter also worked as an intermediary for newly arrived Westerners. Siam, slowly opening up to the outside world, rich in natural resources, and populated by four million pagan souls, attracted a new wave of both fortune seekers and God’s soldiers, many of whom crossed paths with Hunter. During the 1826 Burney Mission, which opened British trade with Siam, Captain Henry Burney was eager to seek assistance from Hunter, who was indeed present, at the captain’s personal request, when the mission was received in audience by Rama III.1 Hunter was also there when the American envoy Edmund Roberts was negotiating treaty terms with the king in 1835, and, in fact, Hunter helped to correct an intentional mistranslation by a Siamese interpreter who tried to smooth over a potential conflict. According to William Ruschenberger, who accompanied Roberts, “The King stated that the Americans were on a footing with the English, which Mr. Roberts denied; saying that such was not the spirit of the Treaty. The secretary nearest the King translated the reply; that Mr. Roberts admitted it, and was very much obliged to His Majesty. Mr. Hunter, who was present, informed Mr. Roberts of the misinterpretation. He repeated what he had at first said, which was then correctly rendered.”2

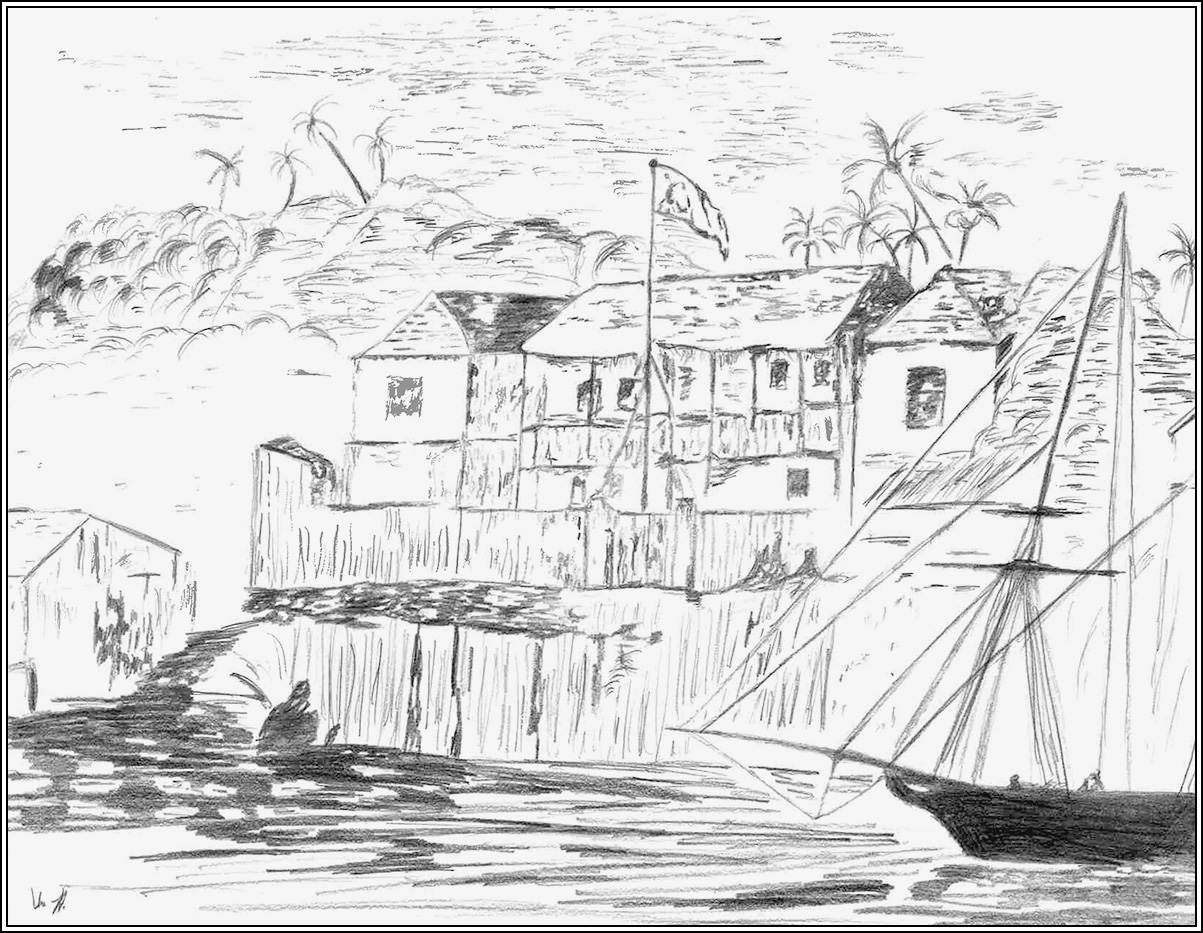

With no inns or hotels available, foreign visitors often had to rely on the hospitality of local hosts, such as Hunter, to put them up for a few nights or even weeks. Even as late as 1862, Anna Leonowens, for instance, still had trouble finding lodging upon her arrival in Bangkok and almost had to sleep under the stars until a gracious host rescued her from her plight. Hunter’s house in Bangkok was a hub for these sojourners and a center of activity. When he first arrived, Hunter had lived in a floating house, “double the size of any of the others, very neatly painted, well furnished, with a nice little verandah in front.” Not fond, however, of the dampness of a floating house, Hunter soon bought timbers and built a European-style grand mansion on the east bank of the Meinam. It was described as “a large white washed brick building two stories in height, and forming three sides of a square, the fourth being closed by a high brick wall. The ground floor was appropriated to warehouses, kitchen, and servants’ quarters, the upper portion being occupied by the Europeans.”3 According to Frederick Arthur Neale, who served as a military officer in Siam, Hunter’s new residence was “a very fine prominent house, opposite to which the British ensign proudly floated on feast days, and here every stranger found a home, for a very prince of hospitality was Mr. Hunter.” Neale, who had stayed with Hunter for a long time, later recalled the leisurely fashion in which visitors conducted business and enjoyed hospitality at Hunter’s:

We breakfasted at ten and after that meal were wont to walk backwards and forwards on the splendid balcony Mr. Hunter had erected, as much for the sake of exercise as to enjoy an uninterrupted half hour’s chat. Then Mr. Hunter betook himself to his counting house. . . . Occasionally we amused ourselves at Mr. Hunter’s by playing Lagrace and we were once or twice guilty of a game at ringtaw. Night, however, brought with it its enlivening candle lights. The darker and more stormy the night, the more brilliantly illuminated the rooms used to be, and if the weather was particularly damp, we made ourselves comfortable with a good dinner and some fine old sherry, and then as a wind up, a drop of hot whisky toddy. . . . One hour before midnight, as indicated by the old clock at Mr. Hunter’s house, was the signal for us to disperse for the night, and long before that time arrived, the whole city was hushed in deep repose.4

Given its reputation and importance, Hunter’s house, known in Siamese as “Hang Huntraa,” was dubbed the “British Factory.”

Among the guests Hunter hosted were Jacob Tomlin and Karl Gutzlaff, who arrived in August 1828 as the earliest Protestant missionaries to Siam. Sent by the London Missionary Society, Tomlin was from Lancashire with a degree from Cambridge and nothing else to brag about, whereas Gutzlaff was a German whose colorful exploits would leave a large footprint in Asia.5 Condemning Buddhism as a “system of the grossest lies,” and claiming that all Asians were dishonest, Tomlin and Gutzlaff devoted themselves to saving these pagan souls. Unlike their Roman Catholic predecessors (and competitors), who had kept a low profile in Siam, Tomlin and Gutzlaff were carried away by their Protestant zealotry. They “freely distributed literature regarding the imminent eclipse of false doctrines such as Buddhism,” a brazen act that immediately incurred the wrath of the king, who ordered the expulsion of the two missionaries. But Hunter intervened, protesting that “neither had broken any law and that their presence was allowed under the treaties of 1822 and 1826.”6 Permitted to stay, the Protestant duo went on to produce the first Siamese translation of the Bible, even though they managed to garner only a handful of conversions, chiefly among their Chinese servants and assistants. Ironically, a reverse conversion might have occurred: Before leaving Siam in 1831, Gutzlaff became a naturalized subject of China by being adopted into the clan of Kwo, taking the name Shih-lee and wearing Chinese garb. As described in his journals, he now had to “conform entirely to the customs of the Chinese, and even to dispense with the use of European books.”7 Whether Gutzlaff’s Sinicization meant he truly went native or it was merely a scheme deployed by an overzealous missionary to get closer to the Chinese—it’s more likely the latter—he felt, like many other transients in Bangkok at the time, deeply indebted to Hunter for assistance. This eccentric German, whose name still graces a busy street in Hong Kong, would later play a key role in the diplomatic negotiations during the First Opium War between China and Great Britain.

ROBERT HUNTER’S HOUSE, BANGKOK

Despite his great influence, Hunter was not always successful in his interventions in the foreign affairs of Siam. One time, Hunter took a guest, Captain Wellar of the bark Pyramus, hunting in the fields. Wellar wandered off and found himself within the precincts of a Buddhist monastery, where evening prayers were being held. Unaware of the Buddhist taboo on taking lives, Wellar shot two pigeons, and soon all hell—whether Christian or Buddhist—broke loose. The monks, alarmed by the crackle of firearms on monastery grounds, rushed out to find Wellar nonchalantly collecting his kill. When the monks tried to wrest the pigeons from his hand and to take his gun, a scuffle ensued. Even though they were not the legendary Shaolin monks trained in martial arts, these sons of Muang Tai ganged up on the Westerner who had showed no respect for innocent lives. When Hunter finally caught up with his friend, Wellar had already been knocked out cold. Seething with anger, Hunter went to the Siamese officials and demanded justice, threatening that if the demand was not met, he would “take the Pyramus in front of the royal palace and let the King hear from the mouth of her guns.” As if that was not enough, he further threatened to send for foreign troops and “establish British rule in Siam.” But the king was unperturbed by the threats and rebuffed Hunter by stating that “the monks had their own ecclesiastical judiciary in which he could not meddle.”8 Incidents such as this indicated both the extraordinary position Hunter held at the court and the limits of his influence, which seemed not enough to sway the king’s position on matters of justice or on allowing the conjoined twins to leave the country. For the latter, Hunter would need additional help, and it came in the form of a Bible-thumping American ship captain named Abel Coffin.

Like a character drawn from a Melville novel, Coffin hailed from the whaling port of Newburyport, Massachusetts. A seasoned mariner and shrewd Yankee trader, he had made many trips to Asia, dealing in tea from China and sugar from Siam. In Bangkok, he fell in with the two Protestant missionaries, Tomlin and Gutzlaff, and befriended Hunter, the local business honcho. Coffin might not have cared much for the German chameleon in Chinese pantaloons, but he certainly spent a lot of time with Tomlin and often invited the English missionary to give sermons to his crew on the Sabbath. Tomlin’s Bangkok journals from those years made constant references to Coffin, describing their field trips together and adventures in a “godless country.” On October 13, 1828, Tomlin wrote in his journal, “At the request of Captain Coffin, commander of an American vessel, I went and delivered a short exhortation to his crew from the parable of ‘the publican and the Pharisee.’ ” A few days later, he wrote, “In the afternoon accompanied Captain Coffin within the city walls to see the cavalry and elephants exercised, but were disappointed, none appearing except half a dozen long-tailed ponies mounted by half-naked Siamese, destitute of all martial accoutrements.” Together they also witnessed the most inhuman torture of captives inside cages. As Hunter had done, Coffin went to Tomlin’s rescue when the latter ran afoul of the Siamese for his missionary work. On January 23, 1829, a party of Siamese soldiers searched Tomlin’s house under the pretense of looking for contraband opium, but Coffin put an end to the charade and forced the Phra Klang to apologize for the affront.9

What gave Coffin the unusual power in his dealings with the Siamese was the same thing that had once made Hunter the king’s favorite: firearms. In late 1828 and early 1829, when Rama III was trying to put down a revolt in a vassal state in Laos, he badly needed guns for the military campaign. Coincidentally, Coffin arrived from India with several crates of muskets that he had acquired at an auction in Calcutta. He sold the firearms to the king for a handsome profit, and the king, now with more firepower in his arsenal, quickly quashed the revolt. When he captured the rebel leader, the king put him in a cage and invited Coffin, accompanied by Tomlin as indicated above, to witness the gruesome torture of the captive.

Knowing Coffin’s warm relationship with the king, Hunter, who had looked for every opportunity to advance his interest in the conjoined twins, approached the American ship captain with a proposal: They could become partners if Coffin could persuade the king to let the twins out of the country. A proud son of Puritan forefathers well versed in rhetorical persuasion, Coffin knew just what buttons to push when he broached the topic to Rama III. He appealed to the king’s vanity, suggesting that if he would allow the twins to depart, “the world might behold that the favored empire of Siam could alone produce, of all the nations of the earth, such a living wonder as the famous united brothers.”10 Still intoxicated by his recent military victory and most grateful to the Yankee’s timely infusion of firearms, the king eventually acquiesced. Overjoyed, Hunter and Coffin, though not checking at first with the family, immediately made plans to take the twins out of the country for a world tour.

Like a sign from heaven, a lunar eclipse occurred on March 20, 1829. It was a spectacular view in the night sky over Siam, and there was countrywide commotion. As soon as the dark shadow of the earth crept onto the face of the moon, eating away the silvery disk like a Chinese moon pie, a boisterous cacophony of gongs, drums, cymbals, cooking pots, and washbasins resounded everywhere, mingled with the roar of cannons and muskets fired at irregular intervals. The Chinese and Siamese believed—and still believe to a degree—that a lunar eclipse is caused by a hungry sky dog trying to devour the moon, and that people need to prevent the disaster by scaring away the evil canine with loud noises.11

The waxing and waning of the moon also happens to be a metaphor for the reunion and separation of a family for the Chinese. One can imagine how loudly and passionately Nok, the mother of the twins, was banging her cooking pots during the two-hour lunar eclipse. They had celebrated the Chinese New Year not too long ago, and now her twin boys would leave her for a long journey to the other side of the globe. Her family would not be whole for some time, the eclipse appearing as an ominous sign.

Reluctant as she was to let her twin boys go—they were only seventeen and were the mainstay of the family business—the offer of $500 from Hunter and Coffin (in ways reminiscent of the transactional nature of slavery, though lacking the barbarity and oppression) and the prospect of more money in the future were too tempting to turn down. Besides, the white men had promised to bring back her boys within five years. To further alleviate her worry, an arrangement was made for a Chinese neighbor, a young man named Tieu, to travel with the twins as a companion and caretaker.

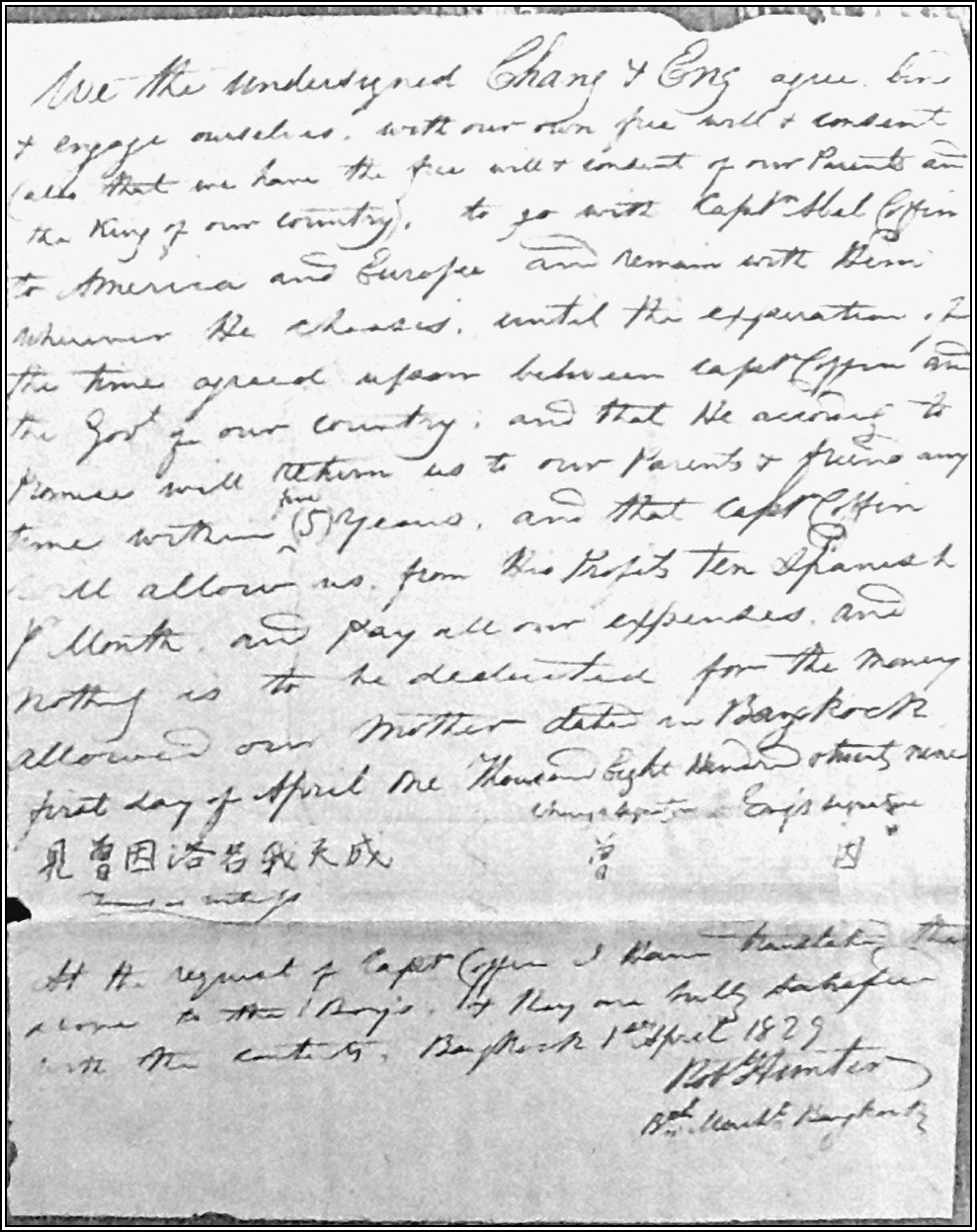

On the day of departure, April Fools’ Day of 1829, the twins signed a contract, a document that has miraculously survived the passage of time to this day. In this contract, handwritten by Hunter and witnessed by Tieu, Chang and Eng agreed “to engage ourselves with our own free will and consent (also that we have the free will & consent of our Parents and the King of our country) to go with Capt. Abel Coffin to America and Europe and remain with him wherever he chooses until the expiration of the time agreed upon between Capt. Coffin and the Govt. of our country, and that he according to promise will return us to our Parents and friends anytime within five (5) years, and that Capt. Coffin will allow us from his profits ten Spanish per month and pay all our expenses, and nothing is to be deducted from the money allowed our mother.”

CONTRACT BETWEEN SIAMESE TWINS AND ROBERT HUNTER/ABEL COFFIN, 1829

Although the contractual provisions were well documented, the physical existence of the contract had remained unknown to the world until 1977, when a descendant of Captain Coffin advertised the family heirloom for sale.12 From this document, which is now in the collection of the Surry County Historical Society in North Carolina, we can shed light on a question that has long puzzled biographers and scholars: the names of the twins. Here we find the explanation of why the famous Siamese Twins came to be known as Chang and Eng. On the contract they signed, their names appear for the first and only time that we know in Chinese as  and

and  .

.

, which means “once” or “increase,” is pronounced in Mandarin Chinese either as /zeng/ or /ceng/, and in Cantonese as /tsang/ or /zang/.

, which means “once” or “increase,” is pronounced in Mandarin Chinese either as /zeng/ or /ceng/, and in Cantonese as /tsang/ or /zang/.  , which means “cause,” is pronounced in Mandarin Chinese as /yin/ and in Cantonese as /yen/. Therefore, Chang and Eng, an anglicized variation of the original “Chun” and “In,” is a phonetic approximation of the Cantonese pronunciations of

, which means “cause,” is pronounced in Mandarin Chinese as /yin/ and in Cantonese as /yen/. Therefore, Chang and Eng, an anglicized variation of the original “Chun” and “In,” is a phonetic approximation of the Cantonese pronunciations of  and

and  .

.

Right next to their signatures is a Chinese sentence scribbled by their witness and travel companion, Tieu:  . The sentence can be translated as “I, Tian Cheng, witnessing Zeng and Yin signing their names.”

. The sentence can be translated as “I, Tian Cheng, witnessing Zeng and Yin signing their names.”  , the first Chinese character in Tieu’s name

, the first Chinese character in Tieu’s name

, is pronounced in Mandarin Chinese as /tian/ and in Cantonese as /tieu/, which explains why he is known as “Tieu.” The Chinese word for “signing” is actually misspelled; it should have been

, is pronounced in Mandarin Chinese as /tian/ and in Cantonese as /tieu/, which explains why he is known as “Tieu.” The Chinese word for “signing” is actually misspelled; it should have been  rather than

rather than  , indicating that Tieu probably had only a rudimentary level of education.

, indicating that Tieu probably had only a rudimentary level of education.

At the bottom of the contract, in a postscript, Hunter added: “At the request of Capt. Coffin I have translated the above to the Boys, and they are fully satisfied with the contract.”

Carrying light luggage and their pet python in a cage, waving teary farewells to their mother and siblings, the “boys” stepped aboard the Sachem—a double-decked, three-masted, 387-ton ship—and sailed for the New World. Unbeknownst to them, they would never see Siam again.