Prologue

Prologue

A Game on the High Seas

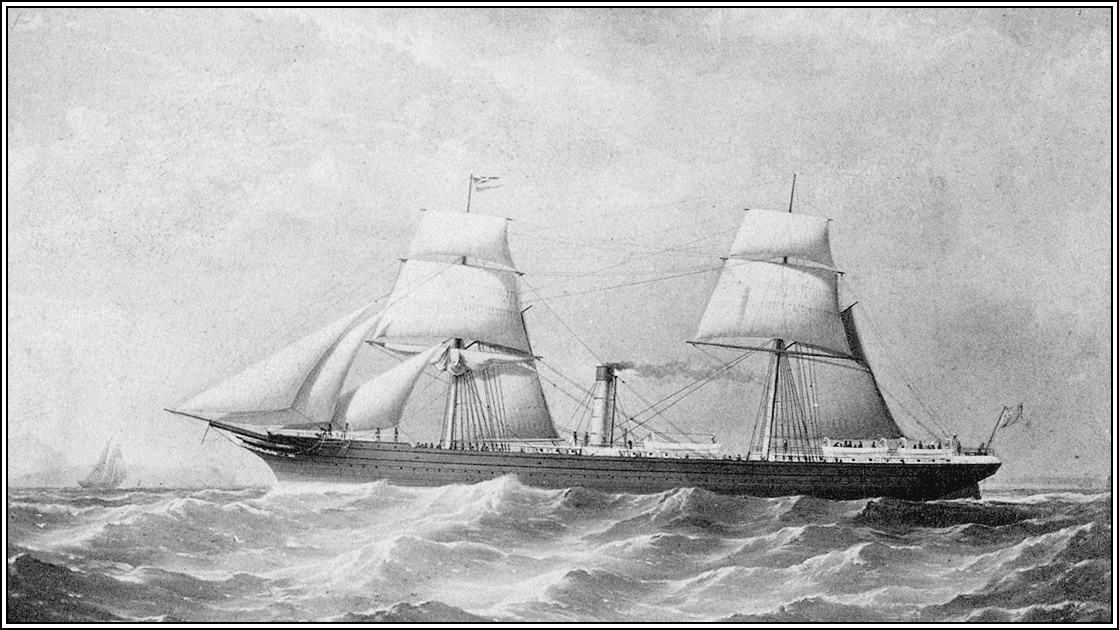

CUNARD STEAMER PALMYRA

It was supposed to be a routine voyage. The Cunard Royal Mail steamer Palmyra left Liverpool on July 30, 1870, setting sail for New York City.

Only five years earlier, the American Civil War had come to a close, with a loss of more than 600,000 lives. Not only had it ineradicably changed the nation and its way of being, it also had abolished the brutal institution of slavery and ended that tragic crossing known as the Middle Passage, a few thousand nautical miles to the south of the Palmyra’s route. The burning embers that had erupted in the wake of General Sherman’s March to the Sea had long since cooled off, but the South remained bitter and defiant, mired in the slow and painful process known as Reconstruction. At the same time, the North, along with the rest of the country, was hurtling along at almost unchecked speed toward the future. Few seemed to heed the backwoodsman Henry David Thoreau’s contrarian wisdom: “Why the hurry?” America was, in fact, in an existential hurry, with the iron horse—the train—leading the charge of economic expansion. The 1869 completion of the transcontinental railroad, built on the backs and lives of Irish and Chinese coolie laborers, had brought the nation together, at least spatially. New towns sprouted along newly laid railroad tracks like bamboo shoots after a spring rain. Cattle kingdoms arose like tumbleweed in Texas and the plains states. The dizzying pace of urban expansion and frenetic economic development had ushered in a new era in America: the Gilded Age.

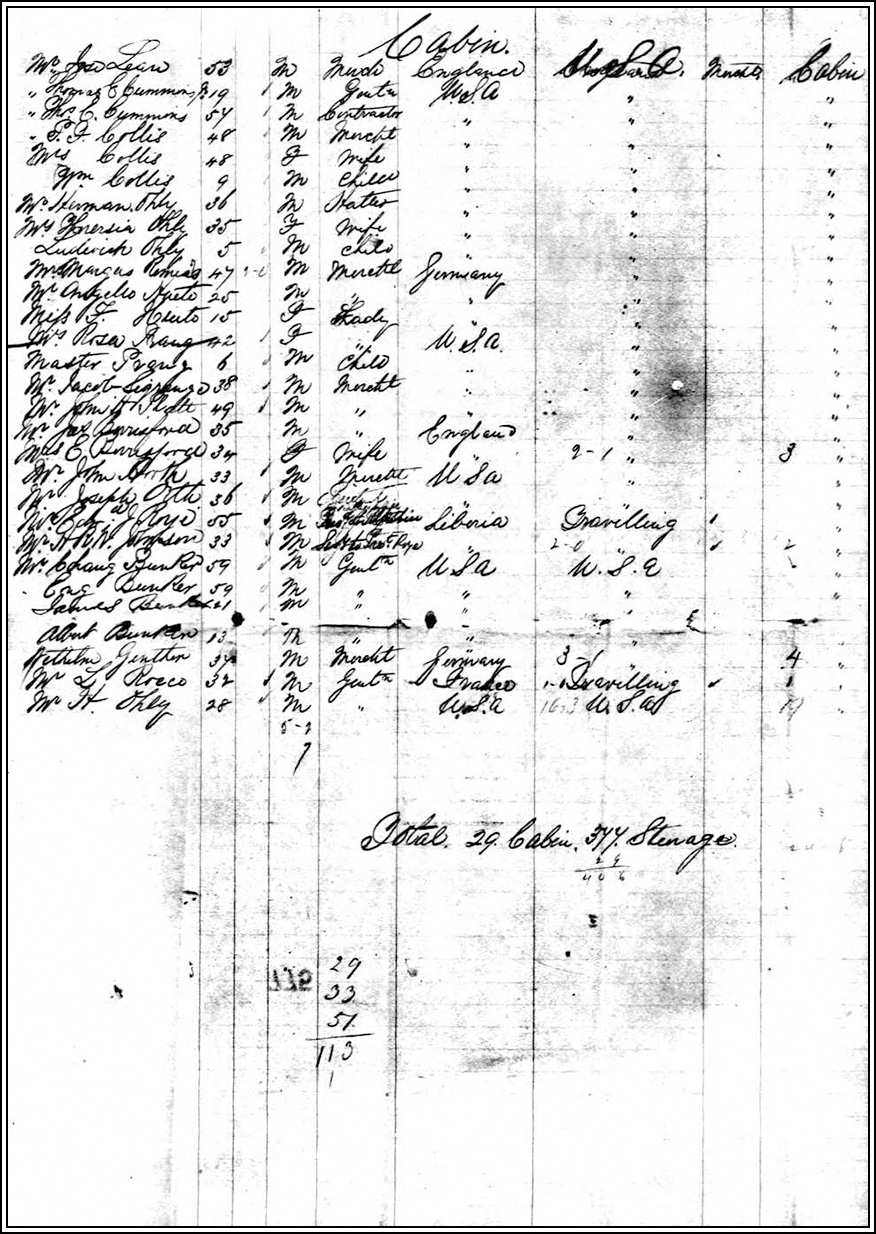

The Palmyra, built in 1866 to keep abreast of the exponential increase in transatlantic traffic, was a medium-size steamship—2,044 in tonnage, 260 in nominal horsepower, and a passenger capacity of forty-six in cabin class and 650 in steerage.1 On this particular westward voyage, the Palmyra, under the command of Captain William Watson, carried 29 passengers in cabin class and 377 in steerage.2

A steamer like the Palmyra was a major improvement on a sailing ship, cutting the length of the transatlantic journey from an almost insufferable eight weeks down to two. However, these were the early days of cruise voyages, with conditions aboard still crude, if not primitive. Cabins were as small as a so-called cat’s ear, dimly lit by a single candle. Passengers had to wash their own dishes. To get fresh milk—before the age of electricity and refrigerators—the company actually carried live cows aboard. To control rats, cats—which, of course, were oblivious to the class divisions of cabin and steerage—were taken along for the cruise.3 Charles Dickens, who had crossed the Atlantic nearly three decades earlier on the SS Britannia to visit the United States, complained bitterly of tasteless food, inebriated cooks, and cramped cabins, about which the famous novelist wrote, “nothing smaller for sleeping in was ever made except coffins.”4 Mark Twain, the globetrotter who coined the term Gilded Age, blessed these newfangled steamships with an even more withering remark in his travelogues, characterizing the meals as “plenty of good food furnished by the Deity and cooked by the devil.”5 Colorful derision aside, the customary seagoing fare was a far cry from what the steamship companies had advertised as the luxury of “a cheerful, hospitable, and elegant Floating Hotel.”6

On her second day at sea, as land faded on the horizon, the Palmyra glided toward the deep waters of the blue Sargasso Sea. The ship’s strong prow sliced through the water like a cheese-cutting knife, spewing fierce foam into the air. After breakfast, cabin passengers began to mingle or disperse. Those who felt queasy went to their cabins, while others lingered behind, engaging in all sorts of trivial pursuits to while away their time. Mr. John H. Slatt, a middle-aged English businessman, strolled on deck with his cane and stared at the vast monotony of the ocean, reminiscing about his first trip to America on the Europa more than twenty years earlier. Mr. Jacob Cigrange, a redheaded merchant, native of Luxembourg and now a proud resident of Fredonia, Wisconsin, lounged on a weatherworn deck chair, watching the vagaries of the clouds. Mrs. Rosa Prang, a Swiss blonde in her early forties, took her six-year-old nephew John to the stern rails to look for whales, porpoises, and sharks, which often frequented this part of the ocean. The boy was especially excited about seeing what the sailors called the Portuguese man-of-war, or Nautilus, that might appear in the ocean in days ahead. Those mystical sea snails, of light violet color under the sun, would ascend to the surface, putting up small “sails” and using their tails as navigating rudders. But there was nothing to see that day under a gray sky, except for scattered whitecaps that could easily be mistaken for sightings of something else.

In her earlier years, Mrs. Prang (née Gerber) had followed the footsteps of her brother and immigrated to America. On that trip from her native Switzerland to Paris, she had met a lanky young Prussian named Louis, whose deep-blue eyes had followed her across the aisle as the crowded four-wheeled diligence rumbled through Alpine mountain roads and flat French countryside. She had not thought much of him at the time, although she had been impressed by his story—he was running away from the Prussian police because he was a revolutionary radical. They went separate ways in Paris, and she set sail for America. Five years later, when one day she was milking cows on her brother’s farm in Ohio, she received a letter from Louis asking her to meet him in Boston and marry him. At the time, she had been entertaining a marriage proposal from a neighboring young farmer. Maybe it was Louis’s piercing blue eyes, or maybe it was his radical ideas and foolish ways, but the letter tantalized her with a future that was at least more appealing than the certain monotony of being a farmer’s wife. Without further reflection, Rosa sold her cows to pay for her fare and headed for Boston.

The first few years of their marriage were hard financially. Louis had tried his hand at manufacturing stationery and leather goods, but he finally found his calling in wood engraving. In 1860, he founded L. Prang and Company, a brand that would soon become recognizable all over the world, for during the Civil War, the company sold millions of battleground maps and pictures of soldier heroes, living or dead. Unknown to Rosa, Louis’s bigger reputation would still lie in the future. After the printing of greeting cards during the 1873 Christmas season, the man Rosa had chosen to marry in a leap of faith would become known in history as the “Father of the American Christmas Card.”7

Aboard the Palmyra, when little John became bored from watching the ocean, Rosa took him to the saloon on the quarterdeck. As they entered, she saw a strange scene unfolding, almost like a stage play. Though the windows were open to let in the fresh air, the saloon door had remained shut to avoid sudden drafts. Without thorough ventilation, the strong smell of tobacco mixed with the ocean’s salty tang. Mr. and Mrs. Herman and Honersia Ohly and their cousin were playing whist at a table with Mr. James Berrisford, an English merchant now living in Ohio. Earlier at breakfast, Rosa had chatted with Berrisford and his wife, Elizabeth, about the midwestern state where she had once milked cows.

The unacknowledged center of attention in the room, however, was a quiet chess game being played at another table. One player, a comely black man in his fifties, wearing a black suit and a bowtie, looked dignified, almost regal. The other player—or, strictly speaking, the other two—looked Asian. Wiry men getting on in years, with salt-and-pepper hair, they had deeply wrinkled faces that resembled maps of Asia. They wore identical, elegantly tailored suits, and, most surprising of all, they appeared to have been sewn together.

The distinguished black man, as hard as he tried to focus on the game, could not help but steal sidelong glances at the conjoined pair sitting across the chessboard. His attention was secretly drawn to the fleshy cord that connected the twins, an object of curiosity that had, in fact, tantalized millions worldwide who had flocked to exhibition halls, museums, ballrooms, pitched tents, or county fairgrounds to witness the famously proclaimed lusus naturae (freak of nature). The twins, who had withstood all probing gazes over the years, whether from queens or councilors, princes or paupers, did not particularly heed the black man’s stealthy stare, nor did they mind the curious looks from fellow passengers who all seemed to be absorbed in their own business of distilling boredom drop by drop.

Before the Cunard Steamship Company had adopted strict policies regarding passenger conduct, the saloon on the quarterdeck used to be much noisier. Musicians, theatrical troupes, and minstrels on tour would perform loudly and freely. Itinerant preachers and other evangelizing speakers would also take the opportunity to deliver speeches, trying to save some souls or change a few minds. According to company records, all this changed after a “memorable disturbance” had occurred in 1846. That year, as the Cunard company record shows,

One Frederick Douglass, a man of color, came from America in the Cambria, then commanded by Captain Judkins, for the purpose of speaking and lecturing in England on the abolition of slavery. . . . Being a second-cabin passenger, he had not the privilege of the quarterdeck; but on the last day, after the saloon dinner, he went aft among the first-class passengers, and delivered himself of a bitter discourse on abolition. . . . A large circle of his supporters gathered round him to hear his speech; those who differed from him also listened with great patience for some time. . . . A New Orleans man, the master of a ship in the China trade, and who had been during the greater part of the voyage, and was more particularly on this occasion, very much intoxicated, poked himself into the circle, walked up to the speaker, with his hands in his pockets and a “quid” of tobacco in his mouth, looked at him steadily for a minute, and then said, “I guess you’re a liar!” The negro replied with something equally complimentary, and a loud altercation ensued between them.

Pretty soon a melee broke out between enraged supporters of the opposing sides, who were “scattered into a dozen stormy groups about the deck.” The chaos lasted for almost an hour, until the captain, with the aid of military officers aboard, finally “lulled the tempest and separated the contending parties.” In the middle of the tumult, as the anonymous company record-keeper noted, referring to Douglass, “this demon of discord had vanished.” Thereafter, the Cunard Steamship Company issued strict regulations on passenger conduct, “to prevent the possible recurrence of such an affair.”8

Since then, the saloon and quarterdeck had become much quieter, and indeed boring, as typified by this moment on the Palmyra. One of the twins—unfortunately, we don’t know which one—was absorbed in the game against the gentleman. He took a long, satisfying pull on a cigar after thoughtfully moving a piece on the board, while the other turned his face away, almost instinctively, as he had done all his life, allowing his twin brother to have his fun. Both twins were said to be excellent at chess, a game they had learned on their first voyage to the New World almost a lifetime earlier. But they did not like playing in opposition to each other, because it would be, as they put it, no more fun than “playing with the right hand against the left.”9 Over the years, they had made a pact: If one plays chess, the other will stay quiet and mind his own business. In fact, due to their unique physical condition—even a simple call of nature would have to be answered in the brotherly presence of the other—they had a pact for everything they did: eating, drinking, sleeping, dressing, washing, conversing, traveling, performing, fighting, hunting, and, yes, lovemaking. Doctors even suspected that they might dream similar dreams, or versions of the same, like musical variations.

Their suave opponent turned out to be none other than Edward James Roye, newly elected president of Liberia. Born on February 3, 1815, in the small town of Newark, Ohio, Roye was the son of a fugitive slave who had escaped from Kentucky and ended up managing a ferry service on the Wabash River in Indiana. As a child, Roye was fortunate to be among the few “colored” kids admitted to the local schools in Ohio. According to one biographer, when Roye gained admittance to Newark High School, his teacher was Salmon Portland Chase, who by 1870 became chief justice of the United States.10 Despite his decent education, Roye began work after high school as a barber, considered a most “suitable” occupation for a black man at the time (Newark would not have its first white barber until 1856). He then attended Ohio University in Athens. A few years later, Roye followed in his father’s footsteps and set out westward, settling down also in Terre Haute, where he bought properties, operated a barbershop, and established the first bathhouse in town.11 Although his business prospered, Roye was disheartened to find that nineteenth-century America was not, if it ever would be, a great place for a free black man. When fortunate enough to be unencumbered by chattel slavery, free blacks were not lucky enough to be free from discrimination, segregation, violence, and the malicious suspicion that their presence posed a threat to the purity of white blood and a temptation to those still bound in slavery.

Ever since the birth of the Republic, the question of what to do with free blacks mingling with white populations had puzzled the Founding Fathers. In 1782, Thomas Jefferson, a hearty worrier over miscegenation but hardly a warrior fighting it, suggested a solution that would gain increasing support in the country: removing free blacks beyond the reach of mixture. Slavery is evil, so reasoned this champion of the natural rights of man and an unapologetic owner of slaves, but abolishing human bondage would pose a greater danger of racial commingling. This fear coincided with the other worry shared by slaveholders: The existence of free blacks would have a corrupting influence on those still in chains. Removing free (and freed) blacks from the United States, as Jefferson suggested, became a magic bullet. Spearheaded by the American Colonization Society (ACS), a movement to plant a colony in West Africa gained traction, leading to the birth of Liberia—first as a colony for American settlers in 1822 and then as a new nation in 1847.12

Unnerved by the worsening race relations in America and lured by the promise of a new start in a free land, Roye joined thousands of African Americans sponsored by the ACS to settle in Liberia. After his arrival there in 1846, Roye, a man of considerable acumen, enjoyed a meteoric rise in the newly founded Republic of Liberia. He first made a fortune in shipping and brokerage, then turned to law and politics, winning election to the Supreme Court. After two years, he was advanced to chief justice. A few months prior to his Palmyra voyage to New York, Roye had been elected president of Liberia. He had just traveled to England, trying to negotiate a loan from London bankers, and now he was on his way to the United States, his native land, to raise funds for building a railroad in his adopted country. But as he would soon find out upon landing, the America of 1870, basking in the glow of the Gilded Age, was still no place for a black man, presidential or not. As the New York Daily Tribune reported on August 17, 1870, Roye and his secretary of state, Hilary R. W. Johnson, who would himself become president of Liberia fourteen years later, had trouble finding a hotel room: “Both gentlemen express themselves much pleased with their visits to the United States, but are not partial to the exclusiveness of a hotel proprietor.”13

PASSENGER LIST OF THE PALMYRA

The Asian twins, with whom Roye was now playing chess, were likewise no strangers to racism. Like Roye, Chang and Eng Bunker were also, against all odds, self-made men. Born on a riverboat in a fishing village in Siam on May 11, 1811, Chang and Eng had from birth been joined at the sternum by a piece of cartilage with a fused liver. At age seventeen, they were taken by British businessman Robert Hunter and American ship captain Abel Coffin to the West for a touring exhibition as freaks of nature. Displaying entrepreneurial talent, the twins later managed to free themselves from their owners and operate the tour on their own. Within a decade, they had made enough money to repair comfortably to rural North Carolina, where they purchased land and bought black slaves. Even worse in the eyes of republican patriarchs like Jefferson, they married two white sisters and fathered twenty-one children, two of whom, James and Albert, age twenty-one and thirteen, were now aboard the Palmyra. If Liberia was a solution to white America’s fear of miscegenation, the Siamese Twins and their boys were the living embodiment of that racial nightmare.

In some ways, the leisurely chess game aboard the Palmyra—a welcome interruption in a monotonous ocean voyage—was indeed an intermission in a large historical drama unfolding in nineteenth-century America. The chain of events, the twists and turns, the jostles and lurches that had brought these three men together for a relaxing game in a newfangled steamship saloon would take more than a book’s worth of narration. The immediate event that had placed the twins aboard at this moment was the recently concluded Civil War—or, as the twins would prefer to call it, the War of Northern Aggression. After the Southern Secession in 1861, the twins had stood staunchly with the Confederacy and sent their two adult sons, Christopher and Stephen, to the battlegrounds to fight the Yankees. Both sons were wounded and captured by the Union Army. Chang and Eng remembered those agonizing days and months during the war. When the news of their sons’ capture came, they sat up by spermaceti candles long into the night and pored over those Prang maps of battlefields—almost as if, by tracing that popular Boston lithographer’s prints, they could somehow track down and recover their lost progeny.

When the war ground to a bitter halt, the twins were thrilled to see their sons, though wounded, come home alive. Other Southerners were not so lucky: The 260,000 Confederate war dead would leave behind roughly 85,000 widows and 200,000 fatherless children. Out of the 111,000 Tar Heelers who went to war, 40,275 (or more than one-third) had died. It was the greatest loss of lives suffered by any Confederate state. Chang and Eng’s anguish came in a different way—they were broke. The war had wiped out their patriotic investment in Confederate bonds, rendered worthless by the defeat of the South. It also decimated their major asset—thirty-two slaves worth about $26,550, according to county tax records of 1864. Under the circumstance, the twins had no choice but to resort to one asset they still possessed: their conjoined bodies.

And so they hit the road again as itinerant showmen. This time, they took along some of their children, occasionally even their wives, to show the world that however abnormal they might look, their double union with two white women, considered freakish and even bestial, was able to produce normal offspring.

Their journey had presently led them to this game of chess with the black man who was a symbol of the Emancipation. As the chess pieces moved across the board on the Palmyra, boatloads of freed blacks were traveling in the opposite direction toward Liberia, a presumed land of liber. In the ensuing months, the same American newspapers that would follow the peregrinations of the Siamese Twins and the Liberian president would also report on the continuing black diaspora to West Africa. The New York Sun, for instance, reported on November 14, 1870: “Two hundred colored men and women from different places in North Carolina sailed on Wednesday for Liberia, where they go to make their homes.”14 Between 1825 and 1893, out of the more than fourteen thousand black settlers who went to Liberia, North Carolina would contribute 2,030, a disproportionately high number,15 though we do not know whether any of the freed slaves formerly owned by Chang and Eng were among those from the Tar Heel State.

Nor do we know who won the chess game, or whether they even finished the match, although the outcome of the bigger game, with human bondage and black emancipation at stake, had already been decided for them by the Civil War. The only thing we do know is that at some point during the game, Roye, the former midwestern small-town black barber-turned-president of a free nation, asked the twins, somewhat offhandedly, a delicate question—and the game ended right then. The twins started to rise. As Eng tried to stand up, he was suddenly pulled down by the fleshy string that tied him to his brother. Over the years, constant tugging had stretched the cord from its original four inches in length to five and a half. Something appeared terribly wrong with Chang; his face looked ashen, and he couldn’t move the right side of his body, the side closer to Eng. According to the New York Times, Chang “was stricken by a paralytic shock.” The twins—both the immobile Chang and the healthy Eng—had to be confined to their berth for the rest of the transatlantic journey.16 The abrupt decline of Chang’s health brought an end to the spectacular and unusual career of the twin brothers. They would never go on the road again.

To fathom the depth and complexity of the story of Chang and Eng, a life—to quote an awestruck and somewhat hyperbolic nineteenth-century newspaper editor—“commencing in a Siamese sampan, ending in the backwoods of North America—a life beginning in the utter obscurity of a fisherman’s hut, passing out amid such noise and notoriety as falls to the lot of only one mortal in ten millions,”17 we need to go back to the very beginning, to that humble houseboat, thatched with attap, afloat on the muddy Meklong River. . . .