Chapter 1

What Is Well-Being?

The real way positive psychology got its start has been a secret until now. When I was president-elect of the American Psychological Association in 1997, my email tripled. I rarely answer phone calls, and I never do snail mail anymore, but because there is a twenty-four-hour-a-day bridge game on the Internet, I answer my email swiftly and diligently. My replies are just the length that fits the time it takes for my partner to play the hand when I am the dummy. (I am seligman@psych.upenn.edu, and you should feel free to email me if you don’t mind one-sentence answers.)

One email that I received in late 1997, however, puzzled me, and I put it into my “huh?” folder. It said simply, “Why don’t you come up to see me in New York?” and was signed with initials only. A couple of weeks later, I was at a cocktail party with Judy Rodin, then the president of the University of Pennsylvania, where I have taught for forty years. Judy, now the president of the Rockefeller Foundation, was a senior at Penn when I was a first-year graduate student, and we both worked in psychology professor Richard Solomon’s animal lab. We became fast friends, and I watched with admiration and more than a little envy when Judy zoomed at an astonishingly young age from president of the Eastern Psychological Association, to chairman of psychology at Yale University, to dean, and to provost at Yale, and then to president at Penn. In between, we even managed to collaborate on a study investigating the correlation of optimism with a stronger immune system in senior citizens when Judy headed the MacArthur Foundation’s massive project on psychoneuroimmunology—the pathways through which psychological events influence neural events which in turn influence immune events.

“Do you know a ‘PT’ who might have sent me an email inviting me to New York?” I asked Judy, who knows everybody who is anybody.

“Go see him!” she gasped.

So two weeks later, I found myself at an unmarked door on the eighth floor of a small, grimy office building in the bowels of lower Manhattan. I was ushered into an undecorated, windowless room in which sat two gray-haired, gray-suited men and one speakerphone.

“We are the lawyers for an anonymous foundation,” explained one of them, introducing himself as PT. “We pick winners, and you are a winner. We’d like to know what research and scholarship you want to do. We don’t micromanage. We should warn you at the outset, however, that if you reveal our identity, any funding we give you will stop.”

I briefly explained to the lawyers and the speakerphone one of my APA initiatives, ethnopolitical warfare (most assuredly not any kind of positive psychology), and said that I would like to hold a meeting of the forty leading people who work in genocide. I wanted to find out when genocides do or do not occur, by comparing the settings surrounding the dozen genocides of the twentieth century to the fifty in settings so rife with hatred that genocide should have occurred but did not. Then I would edit a book about how to avoid genocide in the twenty-first century.

“Thanks for telling us,” they said after just five minutes. “And when you get back to your office, would you send us a one-pager about this? And don’t forget to include a budget.”

Two weeks later, a check for over $120,000 appeared on my desk. This was a delightful shock, since almost all the academic research I had known is funded through tedious grant requests, annoying peer reviews, officious bureaucracy, unconscionable delays, wrenching revisions, and then rejection or at best heart-stopping budget cuts.

I held the weeklong meeting, choosing Derry in Northern Ireland as its symbolic location. Forty academics, the princes and princesses of ethnopolitical violence, attended. All but two knew one another from the social-science circuit. One was my father-in-law, Dennis McCarthy, a retired British industrialist. The other was the treasurer of the anonymous foundation, a retired engineering professor from Cornell University. Afterward, Dennis commented to me that people have never been so nice to him. And the volume Ethnopolitical Warfare, edited by Daniel Chirot and me, was indeed published in 2002. It’s worth reading, but that is not what this story is about.

I had almost forgotten this generous foundation, the name of which I still did not know, when I got a call from the treasurer about six months later.

“That was a super meeting you held in Derry, Marty. I met two brilliant people there, the medical anthropologist Mel Konner and that McCarthy chap. What does he do, by the way? And what do you want to do next?”

“Next?” I stammered, wholly unprepared to solicit more funding. “Well, I am thinking about something I call ‘positive psychology.’” I explained it for about a minute.

“Why don’t you come visit us in New York?” he said.

The morning of this visit, Mandy, my wife, offered me my best white shirt. “I think I should take the one with the worn collar,” I said, thinking of the modest office in lower Manhattan. The office building, however, had changed to one of Manhattan’s swankiest, and now the top-floor meeting room was large and windowed—but still with the same two lawyers and the speakerphone, and still no sign on the door.

“What is this positive psychology?” they asked. After about ten minutes of explanation, they ushered me out and said, “When you get back to your office, would you send us a three-pager? And don’t forget to include a budget.”

A month later, a check for $1.5 million appeared.

This tale has an ending as strange as its beginning. Positive psychology began to flourish with this funding, and the anonymous foundation must have noted this, since two years later, I got another one-line email from PT.

“Is the Mandela-Milosevic dimension a continuum?” it read.

“Hmmm … now what could that mean?” I wondered. Knowing, however, that this time I was not dealing with a crank, I made my best guess and sent PT a long, scholarly response, outlining what was known about the nature and nurture of saints and of monsters.

“Why don’t you come visit us in New York?” was his response.

This time I wore my best white shirt, and there was a sign on the door that read “Atlantic Philanthropies.” The foundation, it turned out, was the gift of a single generous individual, Charles Feeney, who had made his fortune in duty-free shops and donated it all—$5 billion—to these trustees to do good work. American law had forced it to assume a public name.

“We’d like you to gather together the leading scientists and scholars and answer the Mandela-Milosevic question, from the genetics all the way up to the political science and sociology of good and evil,” they said. “And we intend to give you twenty million dollars to do it.”

That is a lot of money, certainly way above my pay grade, and so I bit. Hard. Over the next six months, the two lawyers and I held meetings with scholars and drafted and redrafted the proposal, to be rubber-stamped the following week by their board of directors. It contained some very fine science.

“We’re very embarrassed, Marty,” PT said on the phone. “The board turned us down—for the first time in our history. They didn’t like the genetics part. Too politically explosive.” Within a year, both these wonderful custodians of good works—figures right out of The Millionaire (a 1950s television series, on which I had been imprinted as a teenager, in which a person shows up on your doorstep with a check for a million dollars)—had resigned.

I followed the good work that Atlantic Philanthropies did over the next three years—funding Africa, aging, Ireland, and schools—and I decided to phone the new CEO. He took the call, and I could almost feel him steeling himself for yet another solicitation.

“I called only to say thank you and to ask you to convey my deepest gratitude to Mr. Feeney,” I began. “You came along at just the right time and made just the right investment in the offbeat idea of a psychology about what makes life worth living. You helped us when we were newborn, and now we don’t need any further funding because positive psychology is now self-supporting. But it would not have happened without Atlantic.”

“I never got this sort of call before,” the CEO replied, his voice puzzled.

The Birth of a New Theory

My encounter with that anonymous foundation was one of the high points of the last ten years in positive psychology, and this book is the story of what this beginning wrought. To explain what positive psychology has become, I begin with a radical rethinking of what positivity and flourishing are. First and most important, however, I have to tell you about my new thoughts of what happiness is.

Thales thought that everything was water.

Aristotle thought that all human action was to achieve happiness.

Nietzsche thought that all human action was to get power.

Freud thought that all human action was to avoid anxiety.

All of these giants made the grand mistake of monism, in which all human motives come down to just one. Monisms get the most mileage from the fewest variables, and so they pass with flying colors the test of “parsimony,” the philosophical dictum that the simplest answer is the right answer. But there is also a lower limit on parsimony: when there are too few variables to explain the rich nuances of the phenomenon in question, nothing at all is explained. Monism is fatal to the theories of these four giants.

Of these monisms, my original view was closest to Aristotle’s—that everything we do is done in order to make us happy—but I actually detest the word happiness, which is so overused that it has become almost meaningless. It is an unworkable term for science, or for any practical goal such as education, therapy, public policy, or just changing your personal life. The first step in positive psychology is to dissolve the monism of “happiness” into more workable terms. Much more hangs on doing this well than a mere exercise in semantics. Understanding happiness requires a theory, and this chapter is my new theory.

“Your 2002 theory can’t be right, Marty,” said Senia Maymin when we were discussing my previous theory in my Introduction to Positive Psychology for the inaugural class of the Master of Applied Positive Psychology in 2005. A thirty-two-year-old Harvard University summa in mathematics who is fluent in Russian and Japanese and runs her own hedge fund, Senia is a poster child for positive psychology. Her smile warms even cavernous classrooms like those in Huntsman Hall, nicknamed the “Death Star” by the Wharton School business students of the University of Pennsylvania who call it their home base. The students in this master’s program are really special: thirty-five successful adults from all over the world who fly into Philadelphia once a month for a three-day feast of what’s at the cutting edge in positive psychology and how they can apply it to their professions.

“The 2002 theory in the book Authentic Happiness is supposed to be a theory of what humans choose, but it has a huge hole in it: it omits success and mastery. People try to achieve just for winning’s own sake,” Senia continued.

This was the moment I began to rethink happiness.

When I wrote Authentic Happiness a decade ago, I wanted to call it Positive Psychology, but the publisher thought that “happiness” in the title would sell more books. I have been able to win many skirmishes with editors, but never over titles. So I found myself saddled with the word. (I also dislike authentic, a close relative of the overused term self, in a world of overblown selves.) The primary problem with that title and with “happiness” is not only that it underexplains what we choose but that the modern ear immediately hears “happy” to mean buoyant mood, merriment, good cheer, and smiling. Just as annoying, the title saddled me with that awful smiley face whenever positive psychology made the news.

“Happiness” historically is not closely tied to such hedonics—feeling cheerful or merry is a far cry from what Thomas Jefferson declared that we have the right to pursue—and it is an even further cry from my intentions for a positive psychology.

The Original Theory: Authentic Happiness

Positive psychology, as I intend it, is about what we choose for its own sake. I chose to have a back rub in the Minneapolis airport recently because it made me feel good. I chose the back rub for its own sake, not because it gave my life more meaning or for any other reason. We often choose what makes us feel good, but it is very important to realize that often our choices are not made for the sake of how we will feel. I chose to listen to my six-year-old’s excruciating piano recital last night, not because it made me feel good but because it is my parental duty and part of what gives my life meaning.

The theory in Authentic Happiness is that happiness could be analyzed into three different elements that we choose for their own sakes: positive emotion, engagement, and meaning. And each of these elements is better defined and more measurable than happiness. The first is positive emotion; what we feel: pleasure, rapture, ecstasy, warmth, comfort, and the like. An entire life led successfully around this element, I call the “pleasant life.”

The second element, engagement, is about flow: being one with the music, time stopping, and the loss of self-consciousness during an absorbing activity. I refer to a life lived with these aims as the “engaged life.” Engagement is different, even opposite, from positive emotion; for if you ask people who are in flow what they are thinking and feeling, they usually say, “nothing.” In flow we merge with the object. I believe that the concentrated attention that flow requires uses up all the cognitive and emotional resources that make up thought and feeling.

There are no shortcuts to flow. On the contrary, you need to deploy your highest strengths and talents to meet the world in flow. There are effortless shortcuts to feeling positive emotion, which is another difference between engagement and positive emotion. You can masturbate, go shopping, take drugs, or watch television. Hence, the importance of identifying your highest strengths and learning to use them more often in order to go into flow (www.authentichappiness.org).

There is yet a third element of happiness, which is meaning. I go into flow playing bridge, but after a long tournament, when I look in the mirror, I worry that I am merely fidgeting until I die. The pursuit of engagement and the pursuit of pleasure are often solitary, solipsistic endeavors. Human beings, ineluctably, want meaning and purpose in life. The Meaningful Life consists in belonging to and serving something that you believe is bigger than the self, and humanity creates all the positive institutions to allow this: religion, political party, being green, the Boy Scouts, or the family.

So that is authentic happiness theory: positive psychology is about happiness in three guises—positive emotion, engagement, and meaning. Senia’s challenge crystallized ten years of teaching, thinking about, and testing this theory and pushed me to develop it further. Beginning in that October class in Huntsman Hall, I changed my mind about what positive psychology is. I also changed my mind about what the elements of positive psychology are and what the goal of positive psychology should be.

| Authentic Happiness Theory | Well-Being Theory |

| Topic: happiness | Topic: well-being |

| Measure: life satisfaction | Measures: positive emotion, engagement, meaning, positive relationships, and accomplishment |

| Goal: increase life satisfaction | Goal: increase flourishing by increasing positive emotion, engagement, meaning, positive relationships, and accomplishment |

From Authentic Happiness Theory to Well-Being Theory

I used to think that the topic of positive psychology was happiness, that the gold standard for measuring happiness was life satisfaction, and that the goal of positive psychology was to increase life satisfaction. I now think that the topic of positive psychology is well-being, that the gold standard for measuring well-being is flourishing, and that the goal of positive psychology is to increase flourishing. This theory, which I call well-being theory, is very different from authentic happiness theory, and the difference requires explanation.

There are three inadequacies in authentic happiness theory. The first is that the dominant popular connotation of “happiness” is inextricably bound up with being in a cheerful mood. Positive emotion is the rock-bottom meaning of happiness. Critics cogently contend that authentic happiness theory arbitrarily and preemptively redefines happiness by dragging in the desiderata of engagement and meaning to supplement positive emotion. Neither engagement nor meaning refers to how we feel, and while we may desire engagement and meaning, they are not and can never be part of what “happiness” denotes.

The second inadequacy in authentic happiness theory is that life satisfaction holds too privileged a place in the measurement of happiness. Happiness in authentic happiness theory is operationalized by the gold standard of life satisfaction, a widely researched self-report measure that asks on a 1-to-10 scale how satisfied you are with your life, from terrible (a score of 1) to ideal (10). The goal of positive psychology follows from the gold standard—to increase the amount of life satisfaction on the planet. It turns out, however, that how much life satisfaction people report is itself determined by how good we feel at the very moment we are asked the question. Averaged over many people, the mood you are in determines more than 70 percent of how much life satisfaction you report and how well you judge your life to be going at that moment determines less than 30 percent.

So the old, gold standard of positive psychology is disproportionately tied to mood, the form of happiness that the ancients snobbishly, but rightly, considered vulgar. My reason for denying mood a privileged place is not snobbishness, but liberation. A mood view of happiness consigns the 50 percent of the world’s population who are “low-positive affectives” to the hell of unhappiness. Even though they lack cheerfulness, this low-mood half may have more engagement and meaning in life than merry people. Introverts are much less cheery than extroverts, but if public policy is based (as we shall inquire in the final chapter) on maximizing happiness in the mood sense, extroverts get a much greater vote than introverts. The decision to build a circus rather than a library based on how much additional happiness will be produced counts those capable of cheerful mood more heavily than those less capable. A theory that counts increases in engagement and meaning along with increases in positive emotion is morally liberating as well as more democratic for public policy. And it turns out that life satisfaction does not take into account how much meaning we have or how engaged we are in our work or how engaged we are with the people we love. Life satisfaction essentially measures cheerful mood, so it is not entitled to a central place in any theory that aims to be more than a happiology.

The third inadequacy in authentic happiness theory is that positive emotion, engagement, and meaning do not exhaust the elements that people choose for their own sake. “Their own sake” is the operative phrase: to be a basic element in a theory, what you choose must serve no other master. This was Senia’s challenge; she asserted that many people live to achieve, just for achievement’s sake. A better theory will more completely specify the elements of what people choose. And so, here is the new theory and how it solves these three problems.

Well-Being Theory

Well-being is a construct, and happiness is a thing. A “real thing” is a directly measurable entity. Such an entity can be “operationalized”—which means that a highly specific set of measures defines it. For instance, the windchill factor in meteorology is defined by the combination of temperature and wind at which water freezes (and frost-bite occurs). Authentic happiness theory is an attempt to explain a real thing—happiness—as defined by life satisfaction, where on a 1-to-10 ladder, people rate their satisfaction with their lives. People who have the most positive emotion, the most engagement, and the most meaning in life are the happiest, and they have the most life satisfaction. Well-being theory denies that the topic of positive psychology is a real thing; rather the topic is a construct—well-being—which in turn has several measurable elements, each a real thing, each contributing to well-being, but none defining well-being.

In meteorology, “weather” is such a construct. Weather is not in and of itself a real thing. Several elements, each operationalizable and thus each a real thing, contribute to the weather: temperature, humidity, wind speed, barometric pressure, and the like. Imagine that our topic were not the study of positive psychology but the study of “freedom.” How would we go about studying freedom scientifically? Freedom is a construct, not a real thing, and several different elements contribute to it: how free the citizens feel, how often the press is censored, the frequency of elections, the ratio of representatives to population, how many officials are corrupt, among other factors. Each of these elements, unlike the construct of freedom itself, is a measurable thing, but only by measuring these elements do we get an overall picture of how much freedom there is.

Well-being is just like “weather” and “freedom” in its structure: no single measure defines it exhaustively (in jargon, “defines exhaustively” is called “operationalizes”), but several things contribute to it; these are the elements of well-being, and each of the elements is a measurable thing. By contrast, life satisfaction operationalizes happiness in authentic happiness theory just as temperature and wind speed define windchill. Importantly, the elements of well-being are themselves different kinds of things; they are not all mere self-reports of thoughts and feelings of positive emotion, of how engaged you are, and of how much meaning you have in life, as in the original theory of authentic happiness. So the construct of well-being, not the entity of life satisfaction, is the focal topic of positive psychology. Enumerating the elements of well-being is our next task.

The Elements of Well-Being

Authentic happiness theory comes dangerously close to Aristotle’s monism because happiness is operationalized, or defined, by life satisfaction. Well-being has several contributing elements that take us safely away from monism. It is essentially a theory of uncoerced choice, and its five elements comprise what free people will choose for their own sake. And each element of well-being must itself have three properties to count as an element:

- It contributes to well-being.

- Many people pursue it for its own sake, not merely to get any of the other elements.

- It is defined and measured independently of the other elements (exclusivity).

Well-being theory has five elements, and each of the five has these three properties. The five elements are positive emotion, engagement, meaning, positive relationships, and accomplishment. A handy mnemonic is PERMA. Let’s look at each of the five, starting with positive emotion.

Positive emotion. The first element in well-being theory is positive emotion (the pleasant life). It is also the first in authentic happiness theory. But it remains a cornerstone of well-being theory, although with two crucial changes. Happiness and life satisfaction, as subjective measures, are now demoted from being the goal of the entire theory to merely being one of the factors included under the element of positive emotion.

Engagement. Engagement remains an element. Like positive emotion, it is assessed only subjectively (“Did time stop for you?” “Were you completely absorbed by the task?” “Did you lose self-consciousness?”). Positive emotion and engagement are the two categories in well-being theory where all the factors are measured only subjectively. As the hedonic, or pleasurable, element, positive emotion encompasses all the usual subjective well-being variables: pleasure, ecstasy, comfort, warmth, and the like. Keep in mind, however, that thought and feeling are usually absent during the flow state, and only in retrospect do we say, “That was fun” or “That was wonderful.” While the subjective state for the pleasures is in the present, the subjective state for engagement is only retrospective.

Positive emotion and engagement easily meet the three criteria for being an element of well-being: (1) Positive emotion and engagement contribute to well-being. (2) They are pursued by many people for their own sake, and not necessarily to gain any of the other elements (I want this back rub even if it brings no meaning, no accomplishment, and no relationships). (3) They are measured independently of the rest of the elements. (There is, in fact, a cottage industry of scientists that measures all the subjective well-being variables.)

Meaning. I retain meaning (belonging to and serving something that you believe is bigger than the self) as the third element of well-being. Meaning has a subjective component (“Wasn’t that all-night session in the dormitory the most meaningful conversation ever?”), and so it might be subsumed into positive emotion. Recall that the subjective component is dispositive for positive emotion. The person who has it cannot be wrong about his own pleasure, ecstasy, or comfort. What he feels settles the issue. Not so for meaning, however: you might think that the all-night bull session was very meaningful, but when you remember its gist years later and are no longer high on marijuana, it is clear that it was only adolescent gibberish.

Meaning is not solely a subjective state. The dispassionate and more objective judgment of history, logic, and coherence can contradict a subjective judgment. Abraham Lincoln, a profound melancholic, may have, in his despair, judged his life to be meaningless, but we judge it pregnant with meaning. Jean-Paul Sartre’s existentialist play No Exit might have been judged meaningful by him and his post–World War II devotees, but it now seems wrongheaded (“Hell is other people”) and almost meaningless, since today it is accepted without dissent that connections to other people and relationships are what give meaning and purpose to life. Meaning meets the three criteria of elementhood: (1) It contributes to well-being. (2) It is often pursued for its own sake; for example, your single-minded advocacy for AIDS research annoys others, makes you miserable subjectively, and has gotten you fired from your writing job on the Washington Post, but you persist undaunted. And (3) meaning is defined and measured independently of positive emotion or engagement and independent of the other two elements—accomplishment and relationships—to which I now turn.

Accomplishment. Here is what Senia’s challenge to authentic happiness theory—her assertion that people pursue success, accomplishment, winning, achievement, and mastery for their own sakes—has wrought. I have become convinced that she is correct and that the two transient states above (positive emotion and meaning, or the pleasant life and the meaningful life in their extended forms) do not exhaust what people commonly pursue for their own sakes. Two other states have an adequate claim on “well-being” and need not be pursued in the service of either pleasure or meaning.

Accomplishment (or achievement) is often pursued for its own sake, even when it brings no positive emotion, no meaning, and nothing in the way of positive relationships. Here is what ultimately convinced me: I play a lot of serious duplicate bridge. I have played with and against many of the greatest players. Some expert bridge players play to improve, to learn, to solve problems, and to be in flow. When they win, it’s great. They call it “winning pretty.” But when they lose—as long as they played well—it’s almost as great. These experts play in the pursuit of engagement or positive emotion, even outright joy. Other experts play only to win. For them, if they lose, it’s devastating no matter how well they played; if they win, however, it’s great, even if they “win ugly.” Some will even cheat to win. It does not seem that winning for them reduces to positive emotion (many of the stonier experts deny feeling anything at all when they win and quickly rush on to the next game or play backgammon until the next bridge game assembles), nor does the pursuit reduce to engagement, since defeat nullifies the experience so easily. Nor is it about meaning, since bridge is not about anything remotely larger than the self.

Winning only for winning’s sake can also be seen in the pursuit of wealth. Some tycoons pursue wealth and then give much of it away, in astonishing gestures of philanthropy. John D. Rockefeller and Andrew Carnegie set the model, and Charles Feeney, Bill Gates, and Warren Buffett are contemporary paragons of this virtue: Rockefeller and Carnegie both spent the second half of their lives giving away to science and medicine, to culture and education much of the fortunes they had made in the first half of their lives. They created meaning later in their lives after early lives of winning only for winning’s sake.

In contrast to these “donors,” there are the “accumulators” who believe that the person who dies with the most toys wins. Their lives are built around winning. When they lose, it’s devastating, and they do not give away their toys except in the service of winning more toys. It is undeniable that these accumulators and the companies they build provide the means for many other people to build lives, have families, and create their own meaning and purpose. But this is only a side effect of the accumulators’ motive to win.

So well-being theory requires a fourth element: accomplishment in its momentary form, and the “achieving life,” a life dedicated to accomplishment for the sake of accomplishment, in its extended form.

I fully recognize that such a life is almost never seen in its pure state (nor are any of the other lives). People who lead the achieving life are often absorbed in what they do, they often pursue pleasure avidly and they feel positive emotion (however evanescent) when they win, and they may win in the service of something larger. (“God made me fast, and when I run, I feel His pleasure,” says the actor portraying the real-life Olympic runner Eric Liddell in the film Chariots of Fire.) Nevertheless, I believe that accomplishment is a fourth fundamental and distinguishable element of well-being and that this addition takes well-being theory one step closer to a more complete account of what people choose for its own sake.

I added accomplishment pursued for its own sake because of one of the most formative articles I ever read. In the early 1960s, I was working in psychology professor Byron Campbell’s rat lab at Princeton University, and at that time the umbrella theory of motivation was “drive-reduction” theory: the notion that animals acted only to satisfy their biological needs. In 1959 Robert White had published a heretical article, “Motivation Reconsidered: The Concept of Competence,” which threw cold water on the entire drive-reduction enterprise by arguing that rats and people often acted simply to exert mastery over the environment. We pooh-poohed it as soft-headed then, but White, I discovered on my own long and winding road, was right on target.

The addition of the achieving life also emphasizes that the task of positive psychology is to describe, rather than prescribe, what people actually do to get well-being. Adding this element in no way endorses the achieving life or suggests that you should divert your own path to well-being to win more often. Rather I include it to better describe what human beings, when free of coercion, choose to do for its own sake.

Positive Relationships. When asked what, in two words or fewer, positive psychology is about, Christopher Peterson, one of its founders, replied, “Other people.”

Very little that is positive is solitary. When was the last time you laughed uproariously? The last time you felt indescribable joy? The last time you sensed profound meaning and purpose? The last time you felt enormously proud of an accomplishment? Even without knowing the particulars of these high points of your life, I know their form: all of them took place around other people.

Other people are the best antidote to the downs of life and the single most reliable up. Hence my snide comment about Sartre’s “Hell is other people.” My friend Stephen Post, professor of Medical Humanities at Stony Brook, tells a story about his mother. When he was a young boy, and his mother saw that he was in a bad mood, she would say, “Stephen, you are looking piqued. Why don’t you go out and help someone?” Empirically, Ma Post’s maxim has been put to rigorous test, and we scientists have found that doing a kindness produces the single most reliable momentary increase in well-being of any exercise we have tested.

Kindness Exercise

“Another one-penny stamp increase!” I fumed as I stood in an enormous, meandering line for forty-five minutes to get a sheet of one hundred one-cent stamps. The line moved glacially, with tempers rising all around me. Finally I made it to the front and asked for ten sheets of one hundred. All of ten dollars.

“Who needs one-penny stamps?” I shouted. “They’re free!” People burst into applause and clustered around me as I gave away this treasure. Within two minutes, everyone was gone, along with most of my stamps. It was one of the most satisfying moments of my life.

Here is the exercise: find one wholly unexpected kind thing to do tomorrow and just do it. Notice what happens to your mood.

There is an island near the Portuguese island of Madeira that is shaped like an enormous cylinder. The very top of the cylinder is a several-acre plateau on which are grown the most prized grapes that go into Madeira wine. On this plateau lives only one large animal: an ox whose job is to plow the field. There is only one way up to the top, a very winding and narrow path. How in the world does a new ox get up there when the old ox dies? A baby ox is carried on the back of a worker up the mountain, where it spends the next forty years plowing the field alone. If you are moved by this story, ask yourself why.

Is there someone in your life whom you would feel comfortable phoning at four in the morning to tell your troubles to? If your answer is yes, you will likely live longer than someone whose answer is no. For George Vaillant, the Harvard psychiatrist who discovered this fact, the master strength is the capacity to be loved. Conversely, as the social neuroscientist John Cacioppo has argued, loneliness is such a disabling condition that it compels the belief that the pursuit of relationships is a rock-bottom fundamental to human well-being.

There is no denying the profound influences that positive relationships or their absence have on well-being. The theoretical issue, however, is whether positive relationships qualify as an element of well-being. Positive relationships clearly fulfill two of the criteria of being an element: they contribute to well-being and they can be measured independently of the other elements. But do we ever pursue relationships for their own sake, or do we pursue them only because they bring us positive emotion or engagement or meaning or accomplishment? Would we bother pursuing positive relationships if they did not bring about positive emotion or engagement or meaning or accomplishment?

I do not know the answer to this with any certainty, and I do not even know of a crucial experimental test, since all positive relationships that I know about are accompanied either by positive emotion or engagement or meaning or accomplishment. Two recent streams of argument about human evolution both point to the importance of positive relationships in their own right and for their own sake.

What is the big human brain for? About five hundred thousand years ago, the cranial capacity of our hominid ancestors’ skulls doubled in size from 600 cubic centimeters to its present 1,200 cubic centimeters. The fashionable explanation for all this extra brain is to enable us to make tools and weapons; you have to be really smart to deal instrumentally with the physical world. The British theoretical psychologist Nick Humphrey has presented an alternative: the big brain is a social problem solver, not a physical problem solver. As I converse with my students, how do I solve the problem of saying something that Marge will think is funny, that won’t offend Tom, and that will persuade Derek that he is wrong without rubbing his nose in it? These are extremely complicated problems—problems that computers, which can design weapons and tools in a trice, cannot solve. But humans can and do solve social problems, every hour of the day. The massive pre-frontal cortex that we have is continually using its billions of connections to simulate social possibilities and then to choose the optimal course of action. So the big brain is a relationship simulation machine, and it has been selected by evolution for exactly the function of designing and carrying out harmonious but effective human relationships.

The other evolutionary argument that meshes with the big brain as social simulator is group selection. The eminent British biologist and polemicist Richard Dawkins has popularized a selfish-gene theory which argues that the individual is the sole unit of natural selection. Two of the world’s most prominent biologists, unrelated but both named Wilson (Edmund O. and David Sloan), have recently amassed evidence that the group is a primary unit of natural selection. Their argument starts with the social insects: wasps, bees, termites, and ants, all of which have factories, fortresses, and systems of communication and dominate the insect world just as humans dominate the vertebrate world. Being social is the most successful form of higher adaptation known. I would guess that it is even more adaptive than having eyes, and the most plausible mathematization of social insect selection is that selection is done by groups and not by individuals.

The intuition for group selection is simple. Consider two primate groups, each made up of genetically diverse individuals. Imagine that the “social” group has the emotional brain structures that subserve love, compassion, kindness, teamwork, and self-sacrifice—the “hive emotions”—and cognitive brain structures, such as mirror neurons, which reflect other minds. The “nonsocial” group, equally intelligent about the physical world and equally strong, does not have these hive emotions. These two groups are now put into a deadly competition that can have only one winner, such as war or starvation. The social group will win, being able to cooperate, hunt in groups, and create agriculture. The unrelated set of genes of the entire social group is preserved and replicated, and these genes include the brain mechanisms for the hive emotions and for the belief in other minds—the ability to understand what others are thinking and feeling.

We will never know if social insects have hive emotions and if arthropods have found and exploited nonemotional ways to sustain group cooperation. But positive human emotion we know well: it is largely social and relationship oriented. We are, emotionally, creatures of the hive, creatures who ineluctably seek out positive relationships with other members of our hive.

So the big social brain, the hive emotions, and group selection persuade me that positive relationships are one of the five basic elements of well-being. The important fact that positive relationships always have emotional or engagement or meaning or accomplishment benefits does not mean that relationships are conducted just for the sake of receiving positive emotion or meaning or accomplishment. Rather, so basic are positive relationships to the success of Homo sapiens that evolution has bolstered them with the additional support of the other elements in order to make damn sure that we pursue positive relationships.

SUMMARY OF WELL-BEING THEORY

Here then is well-being theory: well-being is a construct; and well-being, not happiness, is the topic of positive psychology. Well-being has five measurable elements (PERMA) that count toward it:

- Positive emotion (of which happiness and life satisfaction are all aspects)

- Engagement

- Relationships

- Meaning

- Achievement

No one element defines well-being, but each contributes to it. Some aspects of these five elements are measured subjectively by self-report, but other aspects are measured objectively.

In authentic happiness theory, by contrast, happiness is the centerpiece of positive psychology. It is a real thing that is defined by the measurement of life satisfaction. Happiness has three aspects: positive emotion, engagement, and meaning, each of which feeds into life satisfaction and is measured entirely by subjective report.

There is one loose end to clarify: in authentic happiness theory, the strengths and virtues—kindness, social intelligence, humor, courage, integrity, and the like (there are twenty-four of them)—are the supports for engagement. You go into flow when your highest strengths are deployed to meet the highest challenges that come your way. In well-being theory, these twenty-four strengths underpin all five elements, not just engagement: deploying your highest strengths leads to more positive emotion, to more meaning, to more accomplishment, and to better relationships.

Authentic happiness theory is one-dimensional: it is about feeling good and it claims that the way we choose our life course is to try to maximize how we feel. Well-being theory is about all five pillars, the underpinnings of the five elements is the strengths. Well-being theory is plural in method as well as substance: positive emotion is a subjective variable, defined by what you think and feel. Engagement, meaning, relationships, and accomplishment have both subjective and objective components, since you can believe you have engagement, meaning, good relations, and high accomplishment and be wrong, even deluded. The upshot of this is that well-being cannot exist just in your own head: well-being is a combination of feeling good as well as actually having meaning, good relationships, and accomplishment. The way we choose our course in life is to maximize all five of these elements.

This difference between happiness theory and well-being theory is of real moment. Happiness theory claims that the way we make choices is to estimate how much happiness (life satisfaction) will ensue, and then we take the course that maximizes future happiness. Maximizing happiness is the final common path of individual choice. As economist Richard Layard argues, that is how individuals choose and in addition maximizing happiness should become the gold standard measure for all policy decisions by government. Richard, the advisor to both prime ministers Tony Blair and Gordon Brown on unemployment, and my good friend and teacher, is a card-carrying economist, and his view—for an economist—is remarkable. It sensibly departs from the typical economist’s view of wealth: that the purpose of wealth is to produce more wealth. For Richard, the only rationale for increasing wealth is to increase happiness, so he promotes happiness, not only as the criterion by which we choose what to do as individuals, but as the single outcome measure that should be measured by government in order to decide what policies to pursue. While I welcome this development, it is another naked monism, and I disagree with the idea that happiness is the be-all and end-all of well-being and its best measure.

The final chapter of this book is about the politics and economics of well-being, but for now I want to give just one example of why happiness theory fails abysmally as the sole explanation of how we choose. It is well established that couples with children have on average lower happiness and life satisfaction than childless couples. If evolution had to rely on maximizing happiness, the human race would have died out long ago. So clearly either humans are massively deluded about how much life satisfaction children will bring or else we use some additional metric for choosing to reproduce. Similarly, if personal future happiness were our sole aim, we would leave our aging parents out on ice floes to die. So the happiness monism not only conflicts with the facts, but it is a poor moral guide as well: from happiness theory as a guide to life choice, some couples might choose to remain childless. When we broaden our view of well-being to include meaning and relationships, it becomes obvious why we choose to have children and why we choose to care for our aging parents.

Happiness and life satisfaction are one element of well-being and are useful subjective measures, but well-being cannot exist just in your own head. Public policy aimed only at subjective well-being is vulnerable to the Brave New World caricature in which the government promotes happiness simply by drugging the population with a euphoriant called “soma.” Just as we choose how to live by plural criteria, and not just to maximize happiness, truly useful measures of well-being for public policy will need to be a dashboard of both subjective and objective measures of positive emotion, engagement, meaning, good relationships, and positive accomplishment.

Flourishing as the Goal of Positive Psychology

The goal of positive psychology in authentic happiness theory is, like Richard Layard’s goal, to increase the amount of happiness in your own life and on the planet. The goal of positive psychology in well-being theory, in contrast, is plural and importantly different: it is to increase the amount of flourishing in your own life and on the planet.

What is flourishing?

Felicia Huppert and Timothy So of the University of Cambridge have defined and measured flourishing in each of twenty-three European Union nations. Their definition of flourishing is in the spirit of well-being theory: to flourish, an individual must have all the “core features” below and three of the six “additional features.”

| Core features | Additional features |

| Positive emotions Engagement, interest Meaning, purpose | Self-esteem Optimism Resilience Vitality Self-determination Positive relationships |

They administered the following well-being items to more than two thousand adults in each nation in order to find out how each country was doing by way of its citizens’ flourishing.

| Positive emotion | Taking all things together, how happy would you say you are? |

| Engagement, interest | I love learning new things. |

| Meaning, purpose | I generally feel that what I do in my life is valuable and worthwhile. |

| Self-esteem | In general, I feel very positive about myself. |

| Optimism | I’m always optimistic about my future. |

| Resilience | When things go wrong in my life, it generally takes me a long time to get back to normal. (Opposite answers indicate more resilience.) |

| Positive relationships | There are people in my life who really care about me. |

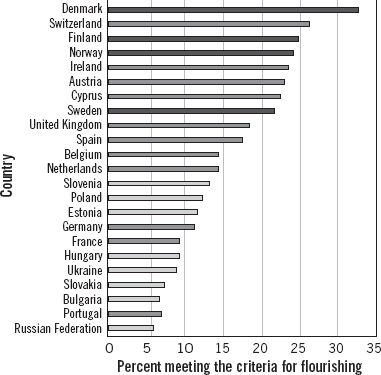

Denmark leads Europe, with 33 percent of its citizens flourishing. The United Kingdom has about half that rate, with 18 percent flourishing; and Russia sits at the bottom, with only 6 percent of its citizens flourishing.

A NEW POSITIVE PSYCHOLOGY

This kind of study leads to the “moon-shot” goal for positive psychology, which is what the final chapter is about and what this book is really aimed at. As our ability to measure positive emotion, engagement, meaning, accomplishment, and positive relations improves, we can ask with rigor how many people in a nation, in a city, or in a corporation are flourishing. We can ask with rigor when in her lifetime an individual is flourishing. We can ask with rigor if a charity is increasing the flourishing of its beneficiaries. We can ask with rigor if our school systems are helping our children flourish.

Public policy follows only from what we measure—and until recently, we measured only money, gross domestic product (GDP). So the success of government could be quantified only by how much it built wealth. But what is wealth for, anyway? The goal of wealth, in my view, is not just to produce more wealth but to engender flourishing. We can now ask of public policy, “How much will building this new school rather than this park increase flourishing?” We can ask if a program of vaccination for measles will produce more flourishing than an equally expensive corneal transplant program. We can ask by how much a program of paying parents to take extra time at home raising their children increases flourishing.

So the goal of positive psychology in well-being theory is to measure and to build human flourishing. Achieving this goal starts by asking what really makes us happy.