5 Life, Happiness, and the Ultimate Time Limit

The older we get, the faster time passes. More routine in life makes experiences less intensive; consequently, the mind retains them with less clarity. Since our subjective experience of life and its span depends on memory, subjective time accelerates as routine increases. A fulfilled and varied life is also a long life. This is very important for many people, since feeling time pass also points to its ultimate end.

I am reading these words now. I see, hear, and feel now. Even when we remember our last vacation or look forward to an excursion tomorrow, memory and anticipation occur now. We make plans for the future and recall memories in the temporal dimension of presence. We survey our past life from the perspective of the present and become aware of its span. Viewed chronologically, this lifetime starts with the first memories of childhood; the light of consciousness dawns, as it were, with our first memories. Our feeling for life’s duration, for periods of life that have passed, is necessarily a matter of remembrance, too.

The feeling of life as time that is limited points to a markedly existential dimension of experience. Many people report the feeling that time seems to pass faster and faster over the course of life. In childhood and adolescence, summer vacations seemed inconceivably long, and the period between Easter and the end of the school year passed far too slowly. Compared to then, five or six weeks fly by now, in adulthood. Likewise, until early adulthood, the academic year—and certainly several years—counted as significant durations of time. In contrast, colleagues at work are quite amazed when they observe how long they have already been working together and how fast—almost unnoticed—the time has passed. Time, it is generally agreed, seems to go faster and faster as we get older.

If only because it is easy to calculate, a popular explanation for this phenomenon is that the relative value of a year, when compared with one’s age, decreases as time increases. A year is one-tenth of a ten-year-old’s life; for someone who is eighty, it amounts to only one-eightieth—in this context, it represents a smaller interval. It is doubtful whether calculations of this kind actually provide the basis for how people experience their lifetime; they merely describe the phenomenon. To explain the feeling of lived time, it makes more sense to consider the dimensions of the past and future. “Time perspective” refers to the concepts of the past, present, and future, which change constantly in the course of life (see chapter 1).

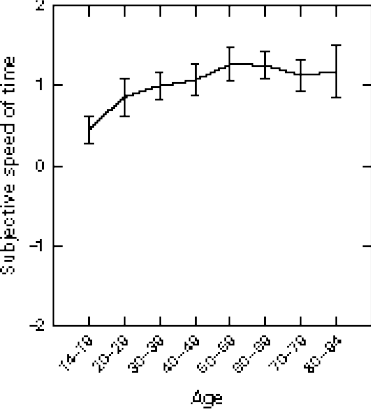

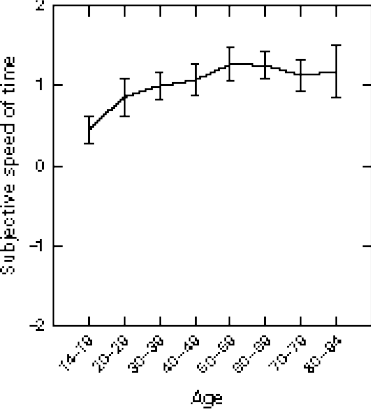

An important factor for understanding the course of time is the past perspective. This has been clearly demonstrated by two large-scale studies conducted with more than 2,000 adult participants, at all stages of life, from metropolitan and rural areas in industrialized countries—Germany, Austria, the Netherlands, and New Zealand:1 in general, adults feel that time is passing quickly; and the higher one’s age, the faster it goes. Adults in the middle years of life indicated that time accelerates markedly between adolescence and young adulthood; this corresponds to common experience.

That said, it is not impossible that the impression of temporal acceleration may be the result of a memory illusion occurring in people over forty, when they are asked to estimate their own life spans retrospectively. For this reason, researchers compared the responses of people of different ages who were asked about their experience of periods that were the same for all participants: a week, a month, a year, and a decade. Here, too, a correlation emerged between age and the subjective speed of time, even though it was less pronounced: the older people were, the faster they perceived the passing of a decade of life. That is to say: past weeks, months, and years do not go faster as age advances; rather, the decades of life do. Researchers determined that the subjective speed of passing decades increases progressively until the sixtieth year of life, when it reaches a plateau; from about this point on, the subjective speed at which time passes remains stable.

Figure 7

Subjective speed in answer to the question, “How fast did the last ten years go by for you?” Respondents, aged 14 to 94, were asked to indicate their feeling of time on a scale: –2 (very slow), –1 (slow), 0 (neither slow nor fast), 1 (fast), 2 (very fast). Up to the age range from 50 to 59, subjective speed increases, after which it remains constant.

In sum, studies demonstrate that time passes quickly for adults on the whole, and a correlation exists between age and temporal perception. However, one should also note the broad range of response behavior among participants, which makes it clear that older people, when compared to younger ones, do not necessarily all have the feeling that time is passing more and more quickly.

Numerous studies from the field of cognitive psychology have shown that the subjective duration of a span of time depends on the number of events stored in memory and the number of changes experienced in this period. The more events or contextual changes that occur within a given stretch of time, the longer it is subjectively experienced.2 Contextual changes concern changes in environment, thought, or feeling. A large quantity of changes perceived over a stretch of time causes duration to expand subjectively, compared to the same span spent under conditions that are monotonous and poor in experience. When a period offers many experiences that can be recalled, it appears to have lasted longer in retrospect. An exciting week on vacation that yielded many new impressions lasts much longer, subjectively, than a week following the same old routine while commuting between home and the office.

In Thomas Mann’s Magic Mountain—a novel about how we feel the passage of time, among other things—the “Excursus on the Sense of Time” directly explores how new experiences affect our perception of time. Mann uses the example of the vacation to illustrate how many different experiences during the first few days at an unfamiliar place stretch time in subjective terms. Then, after one has spent a while at the new location, the days shorten in proportion to the effect of habituation that sets in. Finally, toward the end of the vacation, the days fly by as one realizes that the holiday is rushing to a close.

Experiences that are exciting and new expand time. But when what was novel becomes a matter of routine, time starts to pass quickly again. The narration of The Magic Mountain also develops on the model of how phenomena of perception and memory unfold over an extended span of time. At the outset, detailed descriptions of the first few days at the sanatorium in the Alps fill page after page. The novel’s protagonist, Hans Castorp, views his surroundings and the events there with new eyes, and so there is much that warrants telling. Hours take up whole pages. Later on, the same amount of space is devoted to weeks and even months; far longer stretches of time must pass for the same number of pages to be filled.

Israeli researchers have provided empirical proof for Mann’s insight by observing life and the world. At the end of a holiday period, they interviewed people at the beach. The responses provided by forty-one vacationers demonstrated how the time seemed to pass faster and faster over the course of their stay; the first days stretched out, subjectively, and then they grew shorter and shorter.3 In addition, the researchers showed that people whose professions involved more routine experienced time as passing more quickly than others.

In this context, to fully understand the experience of temporal duration, we should mention the time paradox.4 Temporal duration is evaluated differently depending when the judgment of time is made. A prospective judgment of time occurs when a person estimates the duration of an event while it is still happening. That is, she actively directs her attention to the course of time. We make retrospective judgments by assessing the length of time after the conclusion of an event—that is, by looking back at it. Wholly different cognitive processes are thought to occur in these two forms of temporal perception. While waiting at the doctor’s—when one is paying attention to time (prospective)—half an hour may pass in an intolerably slow fashion. In hindsight, however, it is almost impossible to remember anything, since nothing interesting happened; retrospectively, the span of time shrinks to a negligible quantity. Under other circumstances—say, half an hour spent talking to an interesting person—we are not even aware of the passing of time; in the end, time has gone by far too quickly. But afterward, we can recall so many stimulating moments that the event seems to have lasted a long time.

The time paradox holds for shorter temporal durations—when we first experience half an hour of lived time and then look back at the same interval. However, when it is a matter of evaluating years or decades—as is the case for a lifetime—only the retrospective dimension, that is, the fullness of memory, plays a role.

Fuller Experience Means Longer Life

When asked, older people sometimes express dissatisfaction about time slowing down, which they experience as unpleasant.5 This seems to contradict what we have assumed until now—that we in fact experience time passing more quickly as we age. However, the matter can be understood in the context of the everyday life of people who do not experience a waking period filled with satisfying tasks; as a result, time seems to trickle slowly (prospective). For example, studies of residents in retirement homes report how the lack of varied activities in a monotonous daily routine leads to the feeling that time is passing slowly—meaning the flow of time over the course of the day.6 Boredom, in this context, amounts to the feeling that time is passing slowly. Nevertheless, the same people also report that they feel time passing faster and faster as they get older; here, they have years in mind. Accordingly, it is important to pay attention to which kind of temporal experience is being discussed. When periods of life in the past are at issue, people regularly report that time seems to be accelerating.

The development human beings experience over the course of life offers a key for understanding the role that age plays in the sense that time is passing more quickly.7 From a psychological perspective, childhood, youth, and early adulthood are phases of life marked by the accumulation of constantly new experiences: the birth of a younger sibling, the first day of school, the first vacation spent without parents, the first kiss, and so on. Three years of childhood mean enormous development and countless learning experiences. A twelve-year-old is still a child, but a fifteen-year-old can be almost an adult. In young adulthood (as a rule), one finishes school and gains independence from one’s parents; professional training or college follows; finally, the first real job comes—at the same time, perhaps, a stable partnership. Later in adulthood, in contrast, experiences that are really new decrease; in professional and private life, little change takes place. Three years of adult life often mean three years of routine: getting up, going to work, watching television, sleeping, getting up again, and so on. There is no need for the sameness of experience to be given a separate place in memory. The result is a lower quantity of memory contents; with that, the subjective duration of a given span of time diminishes. The studies of temporal acceleration mentioned above may be explained in this light: inasmuch as people follow more and more routines as they advance in age—experiencing more and more repetition—they encounter and take note of less and less novelty; in consequence, the subjective duration of periods of life shortens.

The finding that only a moderate connection holds between age and the subjective speed of time indicates that no inviolable psychological “law” is at issue. Many studies have demonstrated that the feeling of duration depends on the number of changes experienced and retained by memory; as such, it is possible to influence how time is felt by way of experiences in life. Storing more memories in a given period will result in feeling that a longer time has passed. Here, emotions play a role: events are subject to more frequent and more detailed recollection when they are connected with feelings. In general, we can say that events are stored because they are charged with a certain level of affect.8 Alternatively, the episodes in our lives that we remember depend on the feelings we associate with them. The greater the store of lived experience—that is, the more emotional coloration and variety one’s life has—the longer one’s lifetime seems, subjectively.

With this knowledge, we can formulate directions that may lead to changes in our experience of time. In order to feel that one’s life is flowing more slowly—and fully—one might seek out new situations over and over to have novel experiences that, because of their emotional value, are retained by memory over the long term. Greater variety makes a given period of life expand in retrospect. Life passes more slowly. If one challenges oneself consistently, it pays off, over the years, as the feeling of having lived fully—and, most importantly, of having lived for a long time. Nevertheless, one qualification—which seems rather melancholy—must also be made. As a matter of course, even active and flexible people experience the feeling of repetition at one point or another—say, when one travels to the twentieth exotic land or develops the latest in a long series of innovative business ideas. After all, experience means having done things in life, and so many things and events no longer seem unexpected and novel. What stands out are the experiences that occur for the first time; as such, events from the early phases of life prove especially enduring.

Additionally, we must reflect on the value of our experiences. It takes decades of professional experience to yield expertise that proves invaluable. An extreme change in circumstance—say, moving from one profession to another—can render superfluous all the expert knowledge one has accumulated. Accordingly, one’s subjective experience of his or her lifetime may involve more than deploying the knowledge and skills one has acquired; the trick might be to use them in different contexts, and not always on the same, well-trodden path.

Sigmund Freud stressed that two aspects of life are essential for mental health: the ability to work and the ability to love. Where the second is concerned, the issue of variety proves rather delicate. It is worth considering that the emotional depth achieved in an intensive and lasting relationship might be preferable—even in terms of accumulating life events and the subjective expansion of a lifetime that this entails—to the alternative: soon enough, a series of affairs and short-term relationships will follow the same scheme. Don Juan is the last person to be able to stop time from speeding up.

When We Are Short of Time

We now turn to the future perspective, which must be viewed alongside reference to the past to account for the phenomenon of subjective temporal acceleration.

One study has shown that a heightened fear of death in women between the ages of sixty and eighty-five leads to a more pronounced sense of time slipping away.9 It might be that a future perspective, abbreviated by the anticipation of life’s end, accelerates subjective time. Indeed, critical events in life—for example, illness or unemployment—can shorten the future perspective of people of all ages in a single blow.10 If someone has, say, planned life along the lines of professional training or building a house, the occurrence of such an event will radically abbreviate his or her temporal perspective. Plans now relate only to periods of days or weeks. People with a shortened temporal perspective—which need not stem from sickness or imminent death, but can also result from leaving one’s home country (or just familiar surroundings)—change their social preferences; they seek out others to whom they feel emotionally close. Friends and family become more important than adventures in the mountains on one’s own.

What is more, the common view one occasionally hears—that older people make fewer plans for the future and tend to “live in the past”—is not tenable as such. Even if findings exist for this thesis and show that less openness and controllability shape the personal future of older people, which can lead to a stronger turn to the past, there is evidence that it is mainly the temporal range of future-reference that decreases.11 That is, the number of activities planned for the future does not diminish so much as the temporal interval for which plans are made. Increasingly, long-term plans that span many years and are natural in young and mid-adulthood are replaced by activities that concern the nearer future. Analysis of the intentions of people who are quite old still indicate a large number of anticipated goals. Thus, a pronounced future perspective (even if it is shortened in old age) is connected with personal well-being. The thesis has been refuted that old age entails a crisis in which temporal perspective changes abruptly. As a rule, continuous adaptation to changes in conditions of life shapes the aging process. To be sure, in advanced adulthood, the perception of life’s finitude can play a stronger role. For all that, however, the question of finitude and death does not seem to take precedence in older people; this was determined by the Bonn Longitudinal Study on Aging, in which the same group of people was interviewed as they aged over the course of decades.12 On the whole, problems relating to practical matters of life proved of greatest concern. In everyday life, the subject of death does not necessarily occur to older people more than to younger ones; rather, certain borderline situations—for instance, serious illness—bring the matter home and can prompt a sense of approaching death.13

For older people who are healthy, the subject of death does not predominate—at least on a conscious level. The thought of death typically does not represent a stress factor that would point to time running out and therefore lead to a heightened sense that time is accelerating. Moreover, such a notion cannot explain why the increased acceleration demonstrated in the studies mentioned above occurs at mid-adulthood, and not later. Even fraught experiences such as “midlife crisis,” which can grip people between the ages of thirty-five and fifty and involves an awareness that one’s time is limited,14 cannot explain the gradual acceleration of subjective time as the stages of life unfold. After all, a steady subjective acceleration can already be noted prior to this point—between adolescence and early adulthood, in one’s twenties and thirties.

How, then, may these scientific studies be summarized? In the first place: at least in industrialized nations, people demonstrate the feeling that time passes faster and faster with age.15 Second: studies confirm that subjective temporal duration is decisively shaped by the degree of novelty and emotion in experiences, which determines the amount of memory storage concerning periods in the past. Third: it is possible—even if there is still no hard proof—that the experience of time accelerating with age depends on memory. Because of increasing routine and the decreasing novelty-value of experience that this entails, time seems to accelerate subjectively as fewer and fewer memories are stored over the course of a life.

Death: Experts, Deniers—and Investigators

As one may gather from the Bonn Longitudinal Study of Aging, the theme of death and dying does not stand in the foreground for older people. At the same time, and counter to widespread claims, the matter is not taboo when it comes up in serious conversation. When asked, people are ready to share their thoughts on the subject. In the context of a sociological study about conceptions of death, 150 interviews were analyzed, and three kinds of discourse emerged.16 “Death experts” have a clearly defined image of death, which may be religious in nature or, for that matter, cast in atheistic terms. In either case, death calls for no further investigation because the “experts” consider the answers plain enough: the religious ones know that God exists and there is life after death; the others know that nothing follows biological death. Decidedly religious individuals and atheists hold to an unwavering position that precludes further discussion.

In contrast, for “deniers,” the subject of death is not a topic at all. They are concerned about the health and physical well-being of themselves and their children. They focus on life and avoid talking about death. If these were the only two ways of dealing with the matter, then death and dying would hardly come up at all; death-denial theorists would feel their position confirmed in every respect. However, a third group exists: “death investigators.” These people openly ask themselves questions about death; they feel challenged by death and actively seek answers. As one might expect, sociological analysis of the ways people deal with the meaning of death offers a heterogeneous picture. There are true deniers, but there are also people who confront their mortality out in the open.

What does it mean, then, when the taboo topic of death is mentioned? The psychoanalyst Otto Rank made the ways human beings deal with death the central theme of his study, Psychology and the Soul.17 The idea of the soul’s immortality, he argues, arose in response to our latent fear of death; monotheistic religions, which promise life after death, emerged from this impulse.18 At first, this idea does not seem terribly original, but Rank goes further. As he views it, unconscious forces prevent individuals from thinking about death. Society has created mechanisms, forms of cultural adaptation, that are meant to keep people from becoming conscious of their creaturely (animal) nature—and, therefore, their mortality. Societal taboos and the privatization of biological needs follow from the fact that human beings—just like the neighbor’s dog—have a digestive system and sex drive. Everything about us that might implicate creatureliness and mortality is covered by a cultural “shield.” This may involve religious practices that debase our physicality and exalt our spiritual dimension. For Rank, culture expresses unconscious forces that repress our fear of death.

The Art of a Long Life

Death is quite the popular topic—so long as it is somebody else’s. This much is made plain by the high print runs of detective stories and the success that shows such as CSI have enjoyed for many years. Reading tales of crime in a warm bed or on the sofa often produces a pleasant shudder. When one sits by a roaring fire while a winter storm rages outside, the distance between one’s own safety and danger is palpable. One gets the impression that we learn, from reading accounts of murder, how to face death and dying without danger. The case is almost always solved; things end well with regard to the circumstances of death and the guilty party. Often, the guardians of the law display very human qualities. You can easily identify with the frail, older private detective or the clueless police commissioner who are not unreachable superheroes. One might say that the appeal of murder mysteries lies in the effort to uncover the secrets of death. In fiction, a mystery can be solved that defies explanation in real life.

Figure 8

Ignaz Günther (1725–1775), Chronos, Bavarian National Museum. The work unites time and death in the figure of Chronos, illustrating how the experience of time points to life’s finitude.

Anyone who finds this interpretation somewhat far-fetched may consult the dream theory of the Finnish philosopher and neuroscientist Antti Revonsuo.19 According to Revonsuo, dreams are simulations of taxing situations in life: missing trains and planes, forgetting notes for an important presentation, accidents, and falls. Dream narratives simulate real life in a “safe setting” and help people adjust emotionally to similar occurrences. Of course, dreams may be interpreted in many ways, just as one might read a detective novel for different reasons. But one function such stories perform might be to simulate encounters with death and dying without risk: ultimately, the fiction promises to explain the mystery of death.

That said, if it is not dressed up in criminological literary attire, death hardly represents a popular theme, except to philosophers and those among us whom sociology identifies as “death researchers.” Otto Rank would probably argue that even such anomalous individuals are repressing their actual fear of death. On the one hand, these individuals might be trying to achieve a sense of immortality by producing philosophical treatises; on the other hand, a courageous encounter with this weighty matter might make them feel heroic. Just how bold one is can be determined only on a concrete and individual basis, when we actually have to face dying and it is no longer a matter of books and coffee-house discussions. Empirical investigations related to the “terror management theory” provide evidence of repressed thoughts about death that are revealed through cleverly devised manipulations in psychological experiments.20 Still, it is difficult to know whether death is in fact repressed in life, at least by a majority of people. To put things in the terms of a common critique of psychoanalysis: if we do not agree with the theory of death repression, this is sure proof that it exists.

In his essay On Death,21 the philosopher Ernst Tugendhat steers the opposite course. According to Tugendhat, no autonomous force (unconscious process) represses death; instead, a positive force oriented on life acts on people, making everyone the center of his or her own world. Human beings are suited for life only inasmuch as they possess the will for self-preservation. Accordingly, humankind is focused wholly on life. The matter of death comes up only rarely because we, as biological entities, are designed for survival. We direct our attention to everyday concerns and, in the process, disregard death; there is no need to practice repression actively.

Carpe Diem! The Key to a Long Life

Figure 9

Luca Giordano, La mort de Sénèque, 1684; see note 23 to this chapter.

The brevity of life and dealing with the inevitability of death are one thing. Another is what each person does with the time she or he is given. The Roman statesman and philosopher Seneca got to the heart of the matter in his work On the Shortness of Life:

It is not that we have a short time to live, but that we waste a lot of it. Life is long enough, and a sufficiently generous amount has been given to us for the highest achievements if it were all well invested.22

Born in the first century of the Common Era in Cordoba (Spain), Seneca was a highly respected Roman intellectual of his day.23 All the same, his reflections seem to be modern: his words of caution and exhortation apply to our conditions of life, too. The Stoic makes fun of people who run around pursuing matters they think are important yet always remain dissatisfied. “Salvation” is expected of the time after retirement; then attention will really turn to living:

You will hear many people saying: “When I am fifty I shall retire into leisure; when I am sixty I shall give up public duties.” And what guarantee do you have of a longer life? Who will allow your course to proceed as you arrange it? […] How late it is to begin really to live just when life must end! How stupid to forget our mortality, and put off sensible plans to our fiftieth and sixtieth years, aiming to begin life from a point at which few have arrived!

The Stoic’s moralistic finger is clearly wagging. Indeed, as the empirical studies mentioned above have demonstrated, one often fails to consider one’s own mortality. Research has confirmed the negation of life’s finitude that Seneca addressed—which occurs even at an advanced age. Moreover, in Seneca’s opinion, life only seems short to us—that is, to pass faster and faster—because we waste time on so many useless activities. “Useless” does not necessarily mean lazy Sunday afternoons on the couch. Seneca endorses anything but an unconditional work ethic. On the contrary, he wants to demonstrate that many of our pursuits in life—and especially the work we choose, which eats up all our time—keep us from things that would really prove fulfilling and offer an emotionally rich existence. At this juncture, the reader may reflect on his or her own activities. What is keeping us from doing what we really want to do? In other words: life is, in fact, long, if only we know how to use our time. In the language of memory psychology: Live in such a way that your life is varied and emotionally rich; then you will live for a long time.