Part VI: Arthur in the Modern Age

27

A Postmodern Subject in Camelot: Mark Twain’s (Re)Vision of Malory’s Morte Darthur in A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court

During the last third of the nineteenth century, the United States experienced a vast social and economic upheaval. Westward migration, internal improvements, railroad building, mining, capital investment, industrialization, technological advances, increased economies of scale, monopolies, national advertising and distribution of goods, laissez-faire government policies, immigration, and rapid urbanization transformed a loosely knit country of diverse regions and local economies into a modern nation-state and emerging global power. Industrial and agricultural production skyrocketed, but there arose huge disparities of wealth, hardened class divisions, and mass poverty, especially among former slaves, rural whites, and the over ten million immigrants from non-Anglophone cultures who streamed into the nation. These changes caused a high degree of disorientation and alienation in the national psyche, as previous fundamental assumptions – about the nature of the self, citizenship, government, religion, and morality – seemed increasingly untenable.

Confronted by this fragmented and heterogeneous society, upper- and middle-class whites felt beleaguered. Anglo-American institutions seemed, to them, threatened by “unassimilable” elements: four million ex-slaves, an urban working class of immigrants from Asia and southern and eastern Europe, radical ideologies, labor wars, political scandals, city slums, ward politics, and economic panics. To native-born whites, such developments appeared incompatible with a century-old Jeffersonian vision of an ethnically homogeneous nation of yeoman farmers and republican citizens. With the Civil War receding into memory, a pervasive belief spread that although industrialization and consumerism had produced material comforts, they had also brought “moral complacency, triumphant secularism, and an uneasy sense of artificiality” (Shi 1995: 214). Bourgeois white men felt enfeebled by over-civilization – anemic, feminized, and increasingly vulnerable. There existed a general feeling of “hovering soul-sickness,” a belief that modern life had “grown dry and passionless,” and that culture needed “to regenerate a lost intensity of feeling” (Lears 1981: 142). As America headed toward modernization and modernity, a culture of character, in which one’s sense of self derived from who one was and what one produced, was being replaced by a culture of personality, in which that self arose from how one was viewed by others and what one purchased.

The need for middle-class white males to assert their masculinity, to view themselves as autonomous and empowered subjects, engendered a spirit of martial ardor. This mood nourished a “cult of strenuosity” that included national manias for hiking, bicycling, hunting, fishing, vacations at cowboy “dude” ranches, weightlifting, wrestling, boxing, and football. It also led to the expansion of the YMCA, the city playground movement, physical education classes in schools, and the new popularity of intercollegiate athletics. Among intellectuals in this age of Indian extermination in the west, immigration on the coasts, and incipient American imperialism abroad, the cult of strenuosity was used “to buttress doctrines of racial superiority, military adventure, and territorial expansion”; war itself was viewed as “a therapeutic alternative for a society suffering from social unrest and the anemia of modernity” (Shi 1995: 216–18).

Seeking to restore their feelings of autonomous manhood, white males also sought to construct a usable genealogy in which to anchor themselves. Medievalism had been a pronounced feature of American culture since the 1830s Gothic Revival in architecture. After the Civil War, a new interest in medieval literature emerged, hastened by American translations of medieval French, Italian, and Middle English texts, translations of the writings of medieval mystics, popular biographies of saints and of chivalric knights, and popular adaptations of medieval romances, often written for children (Moreland 1996: 3–4). In his classic study of anti-modernism in American culture during this period, No Place of Grace, T. J. Jackson Lears explores the reasons for medievalism’s strong appeal, here nicely summarized by Kim Moreland:

the fragmented nature of capitalist society, the upper-class fear of class degeneration, the increase in neurasthenia due to the luxury of urban life, the lack of an arena for physical and moral testing, the dissolution of rigorous Protestantism and its replacement by indiscriminate toleration, the emphasis on rationality to the exclusion of powerful emotions, the stifling effect of social and sexual propriety, and the fragmentation of the integral self. (1996: 8)

Toward the end of a century of science, technology, pragmatism, and a teleological faith in secular progress, then, many Americans looked back longingly at a medieval period that they curiously claimed as their own birthright, one they felt was characterized by “[p]ale innocence, fierce conviction, physical and emotional vitality, playfulness and spontaneity, an ability to cultivate fantastic or dreamlike states of awareness, [and] an intense otherworldly asceticism” (Lears 1981: 142).

Mark Twain and American Medievalism

America’s greatest writer, Samuel Langhorne Clemens (1835–1910), was born to impoverished would-be gentry and raised in the slave culture of the antebellum South, but by the mid-1880s he had transformed himself into the world-renowned author Mark Twain: a self-taught, widely read, well-traveled, multilingual, Anglophile intellectual who now resided in Hartford, Connecticut among the New England custodians of culture. As a boy, he had been enchanted by Walter Scott and other romancers widely popular in southern culture, but although deeply nostalgic, he was also a child of the post-Enlightenment and Jeffersonian egalitarian democracy, a spokesman for nineteenth-century America’s faith in moral progress who viewed technological advances as the material manifestation of that progress. To him, the medieval revival “in the midst of the refinement and dignity of a carefully-developed modern civilization” was incongruous. Attending a medieval tournament held in Brooklyn, New York in 1870, he wrote the “doings of the so-called ‘chivalry’ of the Middle Ages were absurd enough, even when they were brutally and bloodily in earnest,” but this new “mock pageantry” was little more than “absurdity gone crazy.” Tongue-in-cheek, he exhorted, “for next exhibition, let us have a fine representation of one of those chivalrous wholesale butcheries and burnings of Jewish women and children, which the crusading heroes of romance used to indulge in in their European homes, just before starting to the Holy Land, to seize and take to their protection the Sepulchre and defend it from ‘pollution’ ” (Budd 1992: 420).

Twain’s personal journey from antebellum southern chauvinist to cosmopolitan champion of human equality, along with his valuation of realist aesthetics, pragmatism, and vernacular ideology in opposition to, respectively, romanticism, devotion to ideality, and genteel literary tastes, had altered his feelings toward Scott, whom he now saw as having promulgated an insidiously anti-democratic imitative culture upon the South of his birth. Returning to the Mississippi River in 1882 after a 21-year absence, he pulled no punches in satirizing his region’s enchantment with the Middle Ages. Twain held Scott “responsible for the Capitol building” in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, a “little sham castle … with turrets and things – materials all ungenuine within and without” and an “architectural falsehood.” Half a century later, “[t]he South has not yet recovered from the debilitating influence of [Scott’s] books. Admiration of his fantastic heroes and their grotesque ‘chivalry’ doings and romantic juvenilities still survives here” (Twain 1883/1984: 285). Among the southern grotesqueries identified by Twain were its bombastic oratory, outmoded codes of honor, love of class and hierarchy (including chattel slavery), backwoods-styled duels and feuds, and such insipid phrases as “the beauty and chivalry” (Twain 1883/1984: 322) used ad nauseam to describe such curiosities as the men and women of New Orleans attending a mule race.

What Twain most hated about southern medievalism was its undoing of the benefits wrought by the French Revolution, which had sundered “the chains of the ancien régime and of the Church,” creating meritocracy and serving the causes of “liberty, humanity, and progress”:

Then comes Sir Walter Scott with his enchantments, and by his single might checks this wave of progress, and even turns it back; sets the world in love with dreams and phantoms; with decayed and swinish forms of religion; with decayed and degraded systems of government; with the sillinesses and emptinesses, sham grandeurs, sham gauds, and sham chivalries of a brainless and worthless long-vanished society. … [In the South] the genuine and wholesome civilization of the nineteenth century is curiously confused and commingled with the Walter Scott Middle-Age sham civilization and so you have practical, common-sense, progressive ideas, and progressive works; mixed up with the duel, the inflated speech, and the jejune romanticism of an absurd past that is dead, and out of charity ought to be buried. … It was Sir Walter that made every gentleman in the South a Major or a Colonel, or a General or a Judge, before the war; and it was he, also, that made these gentlemen value these bogus decorations. For it was he that created rank and caste down there, and also reverence for rank and caste, and pride and pleasure in them. (Twain 1883/1984: 327–8)

He concludes by juxtaposing Scott’s Ivanhoe with Don Quixote, his own favorite novel. Cervantes “swept the world’s admiration for the mediæval chivalry-silliness out of existence; and the other restored it.” In the South, “the good work done by Cervantes is pretty nearly a dead letter, so effectually has Scott’s pernicious work undermined it” (Twain 1883/1984: 328–9).

Twain’s Camelot

Twain may have been contemptuous of contemporary medievalism but he was well-versed in British and Continental history and literature. Despite being closely identified with American subjects and vernacular characters like Tom Sawyer, Huck Finn, Jim, and a host of autobiographical fictional personae, the Middle Ages were, second only to the Missouri of his youth, a touchstone of his later authorial career, forming the setting of four novels, a play, and numerous stories and essays, including 1601 (1880), The Prince and the Pauper (1881), Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc (1896), and four versions of his final novel, No. 44, The Mysterious Stranger (posthumous 1969).

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court (1889) – in which a conflated medieval period from the sixth to the fifteenth centuries serves as the fabula – is a novel rich in interpretive terrain. To genre critics, it is a pioneering work in time-travel science fiction, an early example of American literary naturalism, a satire of Horatio Alger’s popular “rags-to-riches” formula fictions, a dystopia written in the heyday of utopian novels, and a novel that invents the postmodern subject. To cultural critics, it is an anatomy of imperialism (influencing Conrad’s Heart of Darkness and Kipling’s short story “The Man Who Would Be King”), a study in ethnicity and the dynamics of assimilation, a critique of the nineteenth-century’s teleological faith in moral and technological progress, and a literary death blow to the Frontier Myth that had long dominated American ideology. To rhetoricians and political scientists, it is a study of the mindsets of oral versus written cultures, contrasting their respective views on language, narrative, ontology, epistemology, the individual and communal society, the self and state. To historians, it is a critique of the nineteenth-century’s medieval revival, an allegory on the “rise” of western civilization, and a preternaturally predictive book anticipating the nature of such twentieth-century phenomena as modern total warfare, the rise of secular dictators (the protagonist’s title – “The Boss” – is revealingly translated as “Der Fuhrer” and “Il Duce” in German and Italian editions), the uses of propaganda and disinformation by the state in the age of mass communication, and modern campaigns of genocide. Even the name that “The Boss” gives to his program for a democratic republic is predictive, appropriated by Franklin Roosevelt as “The New Deal.”

For those unacquainted with the novel, a brief synopsis will be necessary. Hank Morgan – “a Yankee of Yankees” (Twain 1889/1983: 4), practical, unsentimental, trained in machine and armaments making, and head superintendent at the Colt firearms factory – gets knocked unconscious in an industrial dispute and wakes up in sixth-century England, where he is “captured” by Sir Kay the Seneschal, taken to Arthur’s court, hears endless monologues about improbable adventures, is described by Kay as a “taloned man-devouring ogre” (31), and is condemned to be burned at the stake. Aided by an anachronistically modern-minded page named Clarence, he uses the solar eclipse of 528 to demonstrate his magical powers, and forces Arthur to appoint him perpetual minister and give him one percent of all additional revenue he creates for the state. With Merlin plotting against him, and needing another “miracle” to convince the people of his power, he blows up the tower of his rival magician and becomes “The Boss.”

Over the next seven years Hank brings modern civilization to Camelot, keeping it mostly from public view. During this time, he introduces steel and iron, and hat and textile manufacturing (heavy and light industry); an efficient and equitable tax system (redistributing income to create a home market); free trade (acquiring foreign markets); an insurance industry and stock exchange (capital accumulation and investment); a patent office (encouraging research and development); a national mint (stabilizing currency); a teaching academy and public schools (literacy); military and naval academies (defense); “man factories” (paramilitary units); Protestant denominations (separation of church and state); newspapers, the telegraph, telephone lines, and advertising (mass communication); steamboats and railroads (mass transportation); meritocracy in public and military service (undermining hereditary privilege); public hygiene and a fire department (public safety); and phonographs, typewriters, sewing machines, and baseball (consumer items and entertainment).

Encouraged by Arthur to seek adventures, Hank sets off with Demoiselle Alisande la Carteloise, whom he calls Sandy, in search of a castle where four-armed, one-eyed giants are holding her mistress and forty-four young princesses captive. This sequence – in which he meets commoners and learns of their oppressions, defeats seven knights awed by his pipe smoke, views Morgan le Fay’s cruelty, discovers that the ogres are actually swineherds and the princesses hogs, and again tops Merlin by fixing a Holy Fountain through ostensibly superior magic – gives Twain an opportunity to satirize and contrast the two civilizations. In the next long sequence, Hank and Arthur travel the country incognito. Hank dynamites knights who attack Arthur; the king demonstrates his true nobility by braving smallpox to aid a woman; they observe the aftermath of the murder of a lord and are betrayed, sold into slavery, and view first-hand the barbaric treatment of the poor. In London, condemned to be hanged, they are saved when Launcelot and five hundred knights ride to their rescue on bicycles.

In the final sequences, Hank’s joust with Sagramour, backed by Merlin, turns deadly after he unseats him with a lasso, and he uses a revolver to kill Sagramour and other knights who charge him. With knight errantry broken, Hank reveals his secret civilization to a gadding world and lays plans for undermining the church. He marries Sandy, moves temporarily to the French coast for their child’s health, and, upon returning, discovers all in ruins. Launcelot, in charge of the stock exchange (formerly the Round Table), has engaged in insider trading, causing Agravaine and Mordred to inform Arthur of Launcelot’s affair with Guenever. This leads to civil war, the deaths of Mordred and Arthur, and a church interdict on the country until Hank is dead. With the church in control, Hank retreats to a fortified cave with Clarence and fifty-two trained boys, declares the end of monarchy, nobility, and the established church, and proclaims his republic. His final modern achievement is genocide as Hank uses electrified fences and Gatling guns to slaughter the entire knighthood of England, turning twenty-five thousand men into “homogeneous protoplasm, with alloys of iron and buttons” (Twain 1889/1983: 432). With the fifty-four-man army trapped in their cave and dying from the poisonous fumes of the corpses, a disguised Merlin puts Hank into a thirteen-century sleep and is then grotesquely electrocuted when he backs into the fence.

The inspiration for Connecticut Yankee was Twain’s first encounter with Malory’s Le Morte Darthur in late 1884 (Strachey’s Caxton-based Globe Edition). Initially enchanted, he scribbled a notebook entry:

Dream of being a knight errant in armor in the middle ages. Have the notions & habits of thought of the present day mixed with the necessities of that. No pockets in the armor. No way to manage certain requirements of nature. Can’t scratch. Cold in the head – can’t blow – can’t get at handkerchief, can’t use iron sleeve. … Fall down, can’t get up. (Browning et al. 1979: 78)

A subsequent entry envisaged “a battle between a modern army, with gatling guns – (automatic) 600 shots a minute” and medieval crusaders. A year later, an 1886 entry had the novel titled “The Lost Land.” The time-traveling narrator, back in the nineteenth century, visits England “but it is all changed & become old, so old! – & it was so fresh & new, so virgin before”; he grieves his sixth-century sweetheart, loses interest in life, and commits suicide (Browning et al. 1979: 86, 216). Together, these early plans point to, respectively, a humorous contrast, a violent confrontation between modern and “third-world” military technology, and a sentimental love story – but little plot. As late as November 1886, Twain still had in mind not “a satire peculiarly,” but “a contrast,” claiming “I shall leave unsmirched & unbelittled the great & beautiful characters drawn by the master hand of old Malory” (Wecter 1949: 257–58). In the three chapters already written, the sixth-century characters, except for a buffoonish Merlin, were favorably portrayed. The narrator opines: “there was something very engaging about these great simple-hearted creatures, something attractive and lovable”; a “noble benignity and purity reposed” in Sir Galahad and the king; and “there was majesty and greatness in the giant frame and high bearing of Sir Launcelot” (Twain 1889/1983: 22–3).

All versions of Arthurian legend are dialogical texts, the originary fabula (about which we know little) complexly shaped by socio-historical contexts of the narrating present. As Derek Pearsall notes, Arthurian literature “has provided a medium through which different cultures” can “express their deepest hopes and aspirations and contain and circumscribe their deepest fears and anxieties” (2003: vii). This dynamic is especially foregrounded in Twain’s version because the first-person narrator brings the present and past into direct contact. But although the original idea of a contrast would remain, when Twain returned to the novel, in summer 1887, the intended innocuous romance changed into a comprehensive and devastating satire, one aimed at the culture and institutions of medieval Britain and their perpetuation in late nineteenth-century Britain, then at turn-of-the-century America, and ultimately at the entire history of western civilization.

Twain, Republicanism, and Contemporary Britain

What turned this bland romance into one of the culturally richest and most complex novels of the past two centuries? First, Twain finally read all of Morte Darthur and found it at odds with his earlier readings of Scott, Tennyson, and Sidney Lanier’s bowdlerized version of Malory. Far from being the Golden Age of honor proclaimed by medievalists, it was a world in which Arthur and his knights lie, cheat, steal, break solemn vows, betray friends, and casually slaughter men, women, and children (Bowden 2000: 180–81, 196–7). In addition, events of the previous eighteen months had intervened. As he resumed writing the novel in summer 1887, Twain told William Dean Howells, “When I finished Carlyle’s French Revolution in 1871, I was a Girondin; every time I have read it since, I have read it differently – being influenced & changed, little by little, by life & environment.” Now, he declared: “I am a Sansculotte! – And not a pale, characterless Sansculotte, but a Marat. Carlyle teaches no such gospel: so the change is in me – in my vision of the evidences” (Smith & Gibson 1960: 595, original italics).

Twain possessed a Whig view of history as the secular story of mankind’s evolution from tyranny to liberty. In politics he was ideologically aligned with progressive Republicans at home and the reform wing of the British Liberal Party abroad, several of whose members were his personal friends. In an unpublished manuscript from the late 1880s, he listed the stages by which British civilization had progressed. As Roger Salomon observes, these read like a “check list of Whig-Liberal legislation”: destruction of serfage and slavery, weakening of the church, representative government and extension of suffrage, penal reform, army reform through meritocracy, stripping of privilege from the aristocracy (1961: 27). But during the years when Connecticut Yankee was germinating, the road to progress in Britain seemed impassable. In spring 1885, Gladstone’s ministry fell, with many enfranchised by the Liberal Party’s Reform Act of 1885 voting Conservative. Enforced tithing led to riots in Wales, and attempts to disestablish the Anglican Church were proving futile. Despite some reforms, anti-poaching laws and penalties remained strong, as did the judicial prerogatives of the squirearchy. In 1887, a public education bill was defeated, and class status still determined military commissions. During this time, Twain was pouring through the works of Carlyle, Lecky, Taine, Saint-Simon, and Dickens. He also became friends with George Standring, the radical London printer and recent author of The People’s History of the English Aristocracy. Standring’s book called for replacing the British monarchy with a republic; documented how the ill-gotten wealth of the aristocracy enabled it to control Lords, Commons, manufacturing, the professions, and the military; critiqued the slavish devotion of the British people to royalty; and exposed the crimes and decadence – historical and current – of the nobility (Baetzhold 1970: 102–30 passim).

With his characteristically American conviction that privilege and the concentration of power were insurmountable obstacles to progress, Twain contemplated with disgust Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee, attended by the crowned heads of Europe who were her kin, at the same time as he bridled under Matthew Arnold’s most recent disparagement of America’s democratic culture. He filled his notebooks with increasing fury. To Arnold’s criticism of the American press’s irreverence and America’s predilection for “funny men” like Twain, he wrote, “Irreverence is the champion of liberty, & its only sure defense.” On the English reverence for royalty, he jotted, “Yours is the civilization of slave-making ants” and “How superbly brave is the Eng[lishman] in the presence of the awfulest forms of danger & death; & how abject in the presence of any & all forms of hereditary rank.” His sharpest barbs were reserved for royalty itself: “The kingly office is entitled to no respect; it was originally procured by the highwayman’s methods; it remains a perpetuated crime”; “if you cross a king with a prostitute, the resulting mongrel perfectly satisfies the Eng[lish] idea of ‘nobility’ ”; “The institution of royalty, in any form, is an insult to the human race” (Browning et al. 1979: 392, 398–401, 424).

Connecticut Yankee is informed by these views and critical of pernicious medieval customs that Twain believed had continued into the present. But his critique is not of Malory’s book, passages of which he considered unequalled in eloquence until Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, and part of which – Sir Ector’s eulogy of Launcelot – he quoted at length in his own eulogy of his close friend, General Ulysses S. Grant (Browning et al. 1979: 159, n. 112). Rather, Twain set his fabula in the distant past in order to address the time of narration. This was a strategy he often employed. For example, the last fifth of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884) takes place in the mid-1840s era of slavery but is really a parody on Reconstruction and its aftermath. Likewise, Pudd’nhead Wilson (1894) takes place from 1830 to 1853, but is actually a critique of racism and the color line in the 1890s.

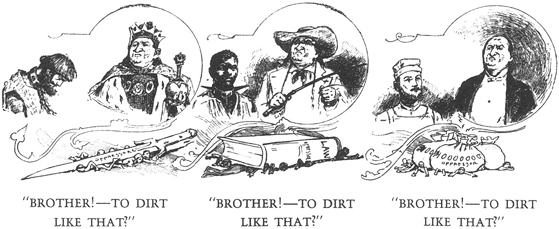

Many of the abuses Twain exposes arise from his hatred of privilege, class hierarchy, and tyranny. The contemporaneousness of these issues is often underscored by the 221 illustrations that appeared in the original 1889 American edition of the book, published in New York by Charles L. Webster. The illustrations were by Dan Beard, the gifted socialist artist whose work the author enthusiastically endorsed. For example, when traveling incognito, Hank advises Arthur to address a commoner as “friend” or “brother” rather than “varlet.” Arthur replies, “Brother! – to dirt like that?” Beard’s illustration is a triptych, with Arthur’s reply written under each pane (figure 27.1). The first shows a king speaking to a peasant, the second an antebellum slaveholder and an African American slave, and the third an industrialist and a factory worker. Under these illustrations respectively are a sword, a law book, and a bag of money with the word “oppressor” written on each (Twain 1889/1983: 275–7).

Figure 27.1 Triptych by Dan Beard, from the first edition of Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court (1889: 363).

Or, as Hank himself puts it, “a privileged class, an aristocracy, is but a band of slaveholders under another name” (239). Sometimes, Beard modeled characters on contemporary personages. When Hank realizes that the “maidens” he has rescued are literally swine, a full-page illustration depicts a popular portrait of Queen Victoria with the face of a hog, the caption reading, “the troublesomest old Sow of the lot” (figure 27.2).

Figure 27.2 “The troublesomest old Sow … ,” Connecticut Yankee (1889: 237).

When Arthur raises an army and ignores the merits of Hank’s West Pointers in favor of unqualified officers of noble birth, another full-page illustration identifies these “chuckleheads” as the Prince of Wales (later Edward VII), his son Prince Albert, and another of Victoria’s grandchildren, Kaiser Wilhelm II (225). Other figures so “honored” include the corrupt American railroad magnate Jay Gould as a satanic slavedriver and Tennyson as a thoroughly ridiculous Merlin (figure 27.3; 359, 21, 211).

Figure 27.3 Portrait of Tennyson as Merlin, Connecticut Yankee (1889: 279).

Hank Morgan often speaks for Twain. Both locate sovereignty in the people and are committed to representative government. Both believe in equality of opportunity and fear concentrations of power. Both share the ideology of republicanism: that power is inherently aggressive and must be restrained by constitutional government in order to protect liberty, and that citizens must be virtuous and civic-minded, joined together in a spirit of mutual responsibility. Hank proudly states:

I was from Connecticut, whose Constitution declares “that all political power is inherent in the people, and all free governments are founded on their authority and instituted for their benefit; and that they have at all times an undeniable and indefeasible right to alter their form of government in such a manner as they may think expedient.” (Twain 1889/1983: 113, original italics)

Hank insists a change in government must issue from the people and not from the enlightened few: “I knew that the Jack Cade or Wat Tyler who tries such a thing without first educating his materials up to revolution-grade is almost absolutely certain to get left” (114). But to do this, he must rid the people of slavish habits of mind they have inherited, most especially “the idea that all men without title and a long pedigree” are “so many animals, bugs, insects” (65). Although “Arthur’s people were of course poor material for a republic, because they had been debased so long by monarchy” (242), Hank believes that “a man is at bottom a man, after all, even if it doesn’t show on the outside” (297) and he has faith that all nations are “capable of self-government” because “in all ages” the greatest minds “have sprung” from “the mass of the nation” and “not from its privileged classes” (242). Thus, his public schools, teaching academies, man-factories, and newspapers are intended to enlighten the masses and prepare them for self-government. His overall plan is: “First, a modified monarchy, till Arthur’s days were done, then the destruction of the throne, nobility abolished, every member of it bound out to some useful trade, universal suffrage instituted, and the whole government placed in the hands of the men and women of the nation” (300).

First-Person Polyphony: Hank Morgan as Postmodern Subject

Although Hank often represents Twain’s point of view, he is no mere authorial persona. Mixed in with his subject positions of egalitarian democrat, advocate of republican government, nineteenth-century liberal, and social reformer are other, less benevolent ideologies. Although he sets up a “variety of Protestant congregations” rather than making “everybody a Presbyterian” (his own sect) because an established church “makes a mighty power” and “means death to human liberty” (Twain 1889/1983: 81), he is aware that democracy is messy and despotism efficient. He admits: “unlimited power is the ideal thing – when it is in safe hands. The despotism of heaven is the one absolutely perfect government.” An earthly despotism, he adds, would be perfect too, but only if the despot and his successors were themselves perfect, an impossibility (81–2).

Power, as republican ideology preaches, corrupts, and Hank proves as corruptible as anyone. Relatively early on, he gives way to ominously imperial and sinister language. “My works showed what a despot could do, with the resources of a kingdom at his command.” He compares his budding civilization to a “volcano, standing innocent with its smokeless summit in the blue sky and giving no sign of the rising hell in its bowels.” Referring to “[m]y schools and churches,” “my little shops,” “my military academy,” “my naval academy,” and Clarence as “my head executive,” he issues a statement chilling to post-Hiroshima readers: “I stood with my finger on the button, so to speak, ready to press it and flood the midnight world with intolerable light at any moment” (Twain 1889/1983: 82–3). Contemplating his “revolution without bloodshed” after defeating knight errantry at the joust, he confesses, “I was beginning to have a base hankering to be its first President myself. Yes, there was more or less human nature in me; I found that out” (399).

Hank’s dilemma is fourfold. First, he does not comprehend the difference between authority and power, roughly analogous to hegemony and coercion. Second, his power is based on his superior technological knowledge. If he educates the people – and can no longer pass off solar eclipses, firearms, and dynamite as personal magic – his power must necessarily vanish. Third, his political ideology locates sovereignty in the people but he cannot bring himself to respect these people, which creates a disjunction between ideology and inclination. Fourth, he is himself an unstable subject, reflecting in his contradictory thoughts and actions the fragmentation of the late-nineteenth-century American national self. He is both humanist and nihilist; essentialist and existentialist; realist and sentimentalist; utilitarian pragmatist and idealist; nineteenth-century liberal and proto-Marxist economist; egalitarian suffragist and totalitarian dictator; advocate of fair trade and free trade; social reformer and genocidal imperialist. A site upon which incompatible ideologies from his own time and place contend, increasingly absorbed into the ethos of the new world he has entered, and continually acquiring and maintaining his sense of self through performance, Hank – literature’s first postmodern subject – possesses no stable set of beliefs upon which to build his program (Lamb 2005: 486–7).

The distinction between power and authority was first recognized by the ancient Mesopotamians in the Enuma Elish (c. 1800–1200 BC), which is both a cosmogonic myth and a kingship epic. The universe’s original elements of chaos seek to destroy the gods of order they have created but, in the first encounter, Ea-Enki defeats his adversary with a spell. Significantly, “this first great victory of the gods over the powers of chaos,” as Thorkild Jacobsen observes, is “won through authority and not through physical force” (1974: 189). But in a second encounter, authority is not enough, and the gods turn to Marduk, a young god possessed of great strength but lacking “influence” (authority). The older gods grant him authority commensurate with theirs and, for the first time in mythopoeic thought, authority and force are united in kingship:

We gave thee kingship, power over all things.

Take thy seat in the council, may thy word prevail. …

The gods, his fathers, seeing (the power of) his word,

Rejoiced, paid homage: “Marduk is king.”

(Jacobsen 1974: 193)

In Twain’s Camelot, the king and his knights possess power. Arthur also combines this with authority through the divine right of kings and his connection with Merlin, who represents through his spells and magic the unexplained residue of dark authority beyond the ken of Christianity (when Merlin begins an incantation to protect his tower from Hank, the people “fell back and began to cross themselves and get uncomfortable” [Twain 1889/1983: 58]). The church, of course, is the ultimate authority in this text, and the main source of Arthur’s. This bifurcation of power and authority is nicely captured in Beard’s illustration of Hugo on the rack in Morgan le Fay’s dungeon, where over his tortured body stand a priest holding a cross and a guard with a spear (154). Hank himself notes: “To be vested with enormous authority is a fine thing; but to have the on-looking world consent to it is a finer. The tower-episode solidified my power, and made it impregnable” (62). Here he links authority with consent (the sovereignty of the people) while properly distinguishing it from power. But he then goes on to call the church a “power” stronger than Arthur’s and his together (63), ignoring the authority that Arthur derives from the church and Merlin, and mistaking the church’s authority for power. Although, in his opinion, he is “a giant among pygmies” because “a master intelligence among intellectual moles,” nevertheless he acknowledges that the people merely “admire” and “fear” him as they would an elephant, but without “reverence mixed with it” (65–7). He could gain this reverence, this portion of authority to go along with his power, were he to accept the title Arthur offers him, but in his eyes it would be illegitimate – because not coming from the people – and so he prefers to win a title through “honest and honorable endeavor” (68). Moreover, he will discover that an aristocracy of “merit is still an aristocracy – an order dependent on political and cultural privilege” in which “the maintenance of social order is still dependent on force” (Slotkin 1985: 530). He ends up caught between the Scylla of having power without authority in a feudal state and the Charybdis of having nothing in a democratic one.

Democracy is also precluded by his perspective toward these people he theoretically considers sovereign. He begins by calling them “childlike,” “white Indians,” “animals,” and “modified savages”; in the end, when they fail to embrace his program because, for all his power, he has failed to win their hearts and minds and gain authority, he calls them “human muck” (Twain 1889/1983: 20, 40, 108, 427). From there to “homogeneous protoplasm” (432) is but a short step.

Hank’s failure to see their humanity, as Thomas Zlatic observes, derives from “the confrontation of a literate mentality with a predominately oral mind-set” (1991: 454 and passim). Oral culture is conservative and communal, with mental energy employed to preserve, through stories of heroic figures in set situations, what is already known. New facts are assimilated to these formulaic stories, with redundancy (copia) the norm so that stories can be remembered and passed along. Such discourse is non-abstract, non-analytical, and non-contextual, and their narrators are un-self-conscious, non-reflective, and matter-of-fact, recognizing no distinction between the ideal and the actual. Hank’s culture, however, with knowledge and stories preserved in writing, prizes individualism, creativity, accuracy, specificity, variety, credibility, and innovative departures from what is known. Narrators like Hank are self-conscious and deeply ironic because they see the discrepancy between the real and the ideal (as when Kay describes a naked Hank as a “horrible sky-towering monster” [Twain 1889/1983: 31]).

Twain understood both oral and written culture. He grew up in the worlds of southwestern humor, African American folklore, western anecdotes, jokes and tall tales, memorized public lecture tours, and piloting, but he was also a prodigious reader in several languages, a professional journalist, and an accomplished printer. Unlike Twain, however, Hank has no appreciation of the communal elements of oral culture; in fact, he views these negatively as a lack of individualism. When Sandy relates the story of Gawaine, Uwaine, and Marhaus (extracted verbatim from Malory’s Morte Darthur, IV, xvi–xix, xxiv–xxv in the Caxton edition), he continually interrupts to mock her, advising her on how to spice up the tale (Twain 1889/1983: 126–34). Viewing her discourse as automatic, he consequently images Sandy as a machine: her unceasing “clack” could “grind, and pump, and churn and buzz” but with no more ideas “than a fog has” (103). Others are similarly imaged as automata. For example, when he encounters St Stylite on a pillar bowing and praying, he concocts a plan “to apply a system of elastic cords to him and run a sewing machine with it” (214). He does gradually develop a mysterious “reverence” for Sandy and sentimentally reconceptualizes her in the image of a nineteenth-century wife and mother, and he makes exceptions for the king whenever Arthur’s innate nobility overcomes his social conditioning, as when he gently carries a girl dying of smallpox to her mother: “the king’s bearing was as serenely brave as it had always been in those cheaper contests where knight meets knight in equal fight and clothed in protecting steel. He was great, now; sublimely great” (286). At moments like this, Hank glimpses value in Arthurian Britain, but mainly he views it as a “dead nation” (74).

The “Triumph” of Technology

The Battle of the Sand-Belt at the end of Connecticut Yankee seems inevitable and anticipates the fighting of the Great War that would commence twenty-five years after the novel’s publication, a war of immobility, trenches, poison gas, machine guns, and anonymous men mechanically turned into corpses, in which the death count arose from a technology that had outstripped both conventional military strategies and moral progress. But the twenty-five thousand knights killed wholesale at the Sand-Belt curiously resemble a culture much like the one Twain critiqued in his attack on the South in Life on the Mississippi, an incongruous mix of the progressive and the medieval, nicely characterized by the traveling-salesmen knights who canvass the countryside dressed in sandwich-board advertisements spreading Hank’s civilization at the point of sword and lance, or by Launcelot and his fellow knights on bicycles. The technology that transforms Camelot was, in real life, transforming the North into an industrial giant and America into a global power. But by 1889 Twain had grown disenchanted with technology and suspicious of man’s capacity for moral growth; his personal investment in the fated Paige typesetter was ruining him financially (Kaplan 1966: 280–311) and technology was undermining both republican values and democratic ideals. If contemporary Britain seemed to him a perpetuation of outmoded feudal institutions, modernizing America seemed increasingly a nightmare. More complexly than the American medievalists who felt a cultural weightlessness and turned to the past for renewal, Twain discovered his nostalgia and progressivism in conflict, and imagined a nearly demonic Hank gleefully demolishing the pillars of the house he has created, damning the past and present with equal force. The symmetry of Merlin defeating Hank with a spell (authority) and then being electrocuted by Hank’s fence (power), as well as Merlin’s grotesque “petrified laugh” (Twain 1899/1983: 443), are fit symbols of the nihilistic conclusion of Connecticut Yankee, an apt fable for the end of a century of progress and a caution to us at the commencement of a century of global ideological strife accompanied by even greater technologies of mass destruction.

Connecticut Yankee concludes with a dying Hank, now “a stranger” in his own time, yearning for his lost Camelot and bemoaning the “abyss of thirteen centuries yawning between … me and my home and my friends! between me and all that is dear to me, all that could make life worth the living!” (Twain 1889/1983: 447). Twain’s own unsentimental, bitter postscript would come in a letter to Howells:

Well, my book is written – let it go. But if it were only to write over again there wouldn’t be so many things left out. They burn in me; & they keep multiplying & multiplying; but now they can’t ever be said. And besides, they would require a library – & a pen warmed up in hell. (Smith & Gibson 1960: 613)

In his final two decades, Twain would increasingly view human beings as little more than machines and wonder if life were, after all, but a walking shadow. These twin visions of despair pervade Connecticut Yankee, with its soulless technocrat narrator and complex dream structure. For Mark Twain, the path to progress would lead, in the end, to an apocalyptic vision and an existential cul-de-sac.

Primary Sources

Browning, R. P., Frank, M. B., & Salamo, L. (eds) (1979). Mark Twain’s notebooks and journals, vol. 3: 1883–1891. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Budd, L. J. (ed.) (1992). Mark Twain: Collected tales, sketches, speeches, and essays, 1952–1890. New York: Library of America.

Fishkin, S. F. (ed.) (1996). The Oxford Mark Twain, 29 vols. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Smith, H. N. & Gibson, W. M. (eds) (1960). Mark Twain–Howells letters: The correspondence of Samuel L. Clemens and William D. Howells, 1872–1910, 2 vols. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Strachey, E. (ed.) (1925). Thomas Malory. Le Morte Darthur (The Globe Edition). London: Macmillan. (Originally published 1868.)

Twain, M. (1983). A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s court. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. (Originally published 1889.)

Twain, M. (1984). Life on the Mississippi. New York: Penguin. (Originally published 1883.)

Wecter, D. (ed.) (1949). Mark Twain to Mrs Fairbanks. San Marino, CA: Huntington Library.

References and Further Reading

Baetzhold, H. G. (1970). Mark Twain and John Bull: The British connection. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Bowden, B. (2000). Gloom and doom in Mark Twain’s Connecticut Yankee, from Thomas Malory’s Morte Darthur. Studies in American Fiction, 28(2), 179–202.

Budd, L. J. (1962). Mark Twain: Social philosopher. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Camfield, G. (2003). The Oxford companion to Mark Twain. New York: Oxford University Press.

Jacobsen, T. (1974). Mesopotamia. In H. Frankfort, H. A. Groenewegen-Frankfort, J. A. Wilson, & T. Jacobsen, Before philosophy: The intellectual adventure of ancient man. New York: Penguin, pp. 135–234.

Kaplan, J. (1966). Mr Clemens and Mark Twain: A biography. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Kasson, J. F. (1976). Civilizing the machine: Technology and republican values in America, 1776–1900. New York: Penguin.

Kordecki, L. C. (1986). Twain’s critique of Malory’s romance: Forma tractandi and A Connecticut Yankee. Nineteenth-Century Literature, 41(3), 329–48.

Lamb, R. P. (2005). “America can break your heart”: On the significance of Mark Twain. In R. P. Lamb & G. R. Thompson (eds), A companion to American fiction, 1865–1914. Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 468–98.

Lears, T. J. J. (1981). No place of grace: Antimodernism and the transformation of American culture, 1880–1920. New York: Pantheon.

Moreland, K. (1996). The medievalist impulse in American literature: Twain, Adams, Fitzgerald, and Hemingway. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press.

Pearsall, D. (2003). Arthurian romance: A short introduction. Oxford: Blackwell.

Powers, R. (2005). Mark Twain: A life. New York: Free Press.

Salomon, R. B. (1961). Twain and the image of history. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Shi, D. (1995). Facing facts: Realism in American thought and culture, 1850–1920. New York: Oxford University Press.

Slotkin, R. (1985). The fatal environment: The myth of the frontier in the age of industrialization, 1800–1890. New York: Atheneum.

Zlatic, T. D. (1991). Language technologies in A Connecticut Yankee. Nineteenth-Century Literature, 45(4), 453–77.