The trick to doing something you’re totally not supposed to do is acting like it’s the most natural thing in the world, like you have every right to be doing it, whatever it is. Sophie pushed her feet into her Vans and passed her mother, asleep on the couch. Her heart pulsed at the sight of Andrea in her work clothes, her head at an odd angle on the couch. It had to be uncomfortable. The woman had to be truly exhausted to have fallen asleep in such an awkward pose, oblivious to the blare of the TV. Sophie thought of turning it down, but then maybe the noise was keeping her mother asleep. What was it about the way Andrea looked, her sleeping mouth open, drool wetting the corners? She looked vulnerable. It gave Sophie a strange, sad feeling. She clicked the door closed gently before she left, praying that her mother wouldn’t stir awake at the sound.

Ella’s strategy was different. The coffee-drinking, gossiping relatives clustered around her kitchen table would stay there long into the night. As distracted as they might be with their lively conversation, they were never too distracted not to know the exact whereabouts of every child in the house. Ella stationed herself with a magazine on the hall floor outside the bathroom. Tia Lucy came by first.

“What are you doing, sitting on the floor by the bathroom?”

Ella slapped shut her magazine with a sigh. “It’s so loud in here,” she groaned. “I can’t even read a stupid magazine. I keep reading the same sentence again and again.”

Tia Lucy clucked her tongue in sympathy. “I hate that,” she said. “You should go over to my house, it’s empty. I got lemonade in the fridge, help yourself. You’re too big to play with the kids and too little to sit with us old ladies.” Tia Lucy laughed as she slid into the bathroom. What a joker. Tia Lucy was hardly an old lady at all. She had long hair she wore in an intricate combination of braid and bun at the back of her head, the better to see the earrings swaying from her ears. Her eyes were lined in blue and she reminded Ella of a bird. Not a dirty Chelsea pigeon but a beautiful, quick bird from a tropical island.

Tia Shirley came next. “What are you doing, reading in the dark? Turn a light on! You’re going to ruin your eyes!”

Ella slapped shut her magazine with a sigh. “The lightbulb burned out. And I can’t read in my room because Tracy and Junior are playing in there, and I can’t read in the living room because Tio Matty and my father are watching something, and I can’t read in the kitchen because you all are so loud.”

Tia Shirley put her hand on her heart and worried her brow, as if a terrible dilemma was before them. “Ella! There has to be a place for you, too! Why don’t you go to my house? Your Tio is sleeping and you can stay on my back porch with the light and read your magazine. Go—I’ll tell your mother.”

“Okay, I probably will,” Ella said.

Sitting on the floor in the hallway, Ella received invitations from two more of her aunts to go and read her magazine at their home. So when she stood at the door, her hand twisting the knob, and hollered into the kitchen, “Okay, I’m going to your house to read my magazine, be back in a couple hours!” the women at the table cried back, “Okay, be careful!” in unison, and Ella walked out the door and headed toward the creek.

* * *

THE SKY OVER Chelsea was extra dark; occasionally the landscape would shift enough for the moon to peek through, illuminating the mass of clouds suffocating its light, and then the cloud cover would spread itself again, and the sky would return to blackness. The glow of the streetlights seemed puny, throwing dim yellow halos around the bulbs but casting hardly any light to the ground. By the time she reached the hole in the chain link, Sophie was going on instinct and memory—beyond the tear in the fence, a shapeless chunk of cement; a bit further, a toppled shopping cart. For a second the clouds shifted, and the moonlight caught on an empty bottle and shone through it to illuminate the path that wound through the tall weeds to the scabby little creek. Sophie headed out on it, wishing that she could smell the water but sort of grateful, she supposed, that she couldn’t, it was so thin and dirty. They were so close to the ocean in Revere, so close to the harbor on the East Boston border, but Sophie and Ella needed the privacy of the creek, their own body of water.

Ella lived closer to the creek and was there already, halfway through a cigarette. When she hugged her, Sophie could feel the day’s sun radiating off her skin. Ella smelled like the tanning oil that stuck stubbornly to her arms, and like the scented lotion she slathered on top of it. Her hair smelled like shampoo and her cigarette smelled slightly of strawberry from the gloss on her mouth. Ella smelled like a girl. Sophie couldn’t imagine what she herself smelled like. She lifted her arm and huffed her armpit.

“Nice,” Ella commented wryly. “Classy.”

“I think I have to start wearing deodorant,” Sophie mused. “Now that I have a job and stuff.”

“Wait, so that’s your actual job?” Ella asked. “Like, you’re getting paid?”

Sophie hedged. “No, I’m not getting paid. But I’m working.”

Ella snorted a last bit of smoke from her nose, like a dragon, and flung her butt in the creek. “That’s not a job, Soph. That’s slavery. There are child labor laws. I bet you could call social services on your mom and they would take you away like that.” Ella snapped her fingers. “Think of it—single mom sends her daughter to the city dump to work, underage, without pay, for her wicked grandmother.”

“It sounds so bad when you say it like that,” Sophie agreed. “But it just feels like being grounded, you know?”

“No, Sophie. Really. Think about it. This could be your lucky break. Social services could take you and place you with, like, some family in the country or something. Or out where the ocean is really pretty, you know, where it’s clean. You could have a dog, and your own room, and food, and I bet the people would be, like, so nice, just really nice people who want to save teenage girls from working at the dump.”

Sophie joined the fantasy. “Or a family in Cambridge,” she said dreamily. Ella wrinkled her nose.

“Cambridge is busted,” she said. “That’s where Ben Affleck is from.”

“Not that part,” Sophie insisted. “The good part of Cambridge, where Harvard is. Maybe I could get adopted by Harvard professors. They’d have a whole room of books, like a library. And real art on the walls, and I’d have my own room and have a pet, even. A dog.”

“A smart dog,” Ella offered. “Not some dumb fucking dog.”

“Yeah,” Sophie said. She imagined herself curled up in a sunny room with a smart dog gazing at her lovingly while she read a really difficult book that she totally understood.

“Or you’d just get thrown in with some pervert and wind up molested,” Ella said.

“Or with one of those couples that live off their foster kid checks,” Sophie concurred. “Like, in a house with fifteen other foster kids. Really awful kids who’d torture cats. Like, put firecrackers up their butts or something.” Sophie shuddered. “People do that, you know.”

“Foster-kid hoarders are creepy.” Ella nodded grimly. “You’re better off where you are.” Ella pulled a green hair elastic from where it sat on her wrist like a bracelet, and pulled her hair into a shiny loop atop her head. “Let’s get to it,” she said. “I want to go first. I didn’t even get to pass myself out last time.”

Sophie looked uneasily at her friend. “I don’t know, Ella,” she said. “I’ve been having some weird things happen to me…”

“You said the doctor told you it was no big deal. You told me she passed herself out when she was our age. And look at her! She’s a friggin’ doctor!”

“I know…” Sophie was feeling wimpy. There was no way to deny it. She felt a wimpy look settle across her face, part a squirmy sort of fear, part shame at the fear, with a tinge of a plea for mercy from her merciless friend.

“Don’t wimp out on me, Swankowski,” Ella said sternly. “If I don’t play pass-out with you, who will I play with? Come on, it’s still fun, don’t you think?”

Sophie recalled the dreamy visions and the sweet body-buzz. She did think it was fun. But passing out felt linked now with those strange feelings and visions, and that desperate need for salt. When she had fixed her bowl of cereal earlier that evening, after her mother had drifted into the living room, Sophie had swiped at the fat, round salt canister in the cupboard and plucked out the spout, sending a fall of the stuff into her Cheerios. Weird. But it had been delicious.

“Just one time,” Ella pushed. “Once for me and once for you. Come on, why did you even want me to meet you out here, if not to play pass-out?”

“Because we’re friends,” Sophie said dumbly.

“Yeah, we’re friends, and this is what we do when we hang out. I smoke and talk too much, you don’t smoke and listen to me, and we pass each other out.” Ella flicked her lighter in the dark, casting enough light for them to find a slight clearing free of dog poop or condoms or jagged smashed bottles. Smaller bits of glass sparkled in the light and reminded Sophie of the recycling shack, of Angel and the tumbler and the bright bins of glass, and she found herself actually excited to return.

“Okay,” Ella said. With her knees in the dirt Ella bent her head and began her huffing and puffing. When she flung herself up Sophie tensed behind her, waiting for her body to begin its slump, to catch her and lay her gently on the ground. She did. She pushed some weeds aside so that they framed her face. Ella, she realized, was beautiful. She always had been, and Sophie had always known it, but Ella’s beauty had always been neck and neck with Sophie’s own. Looking down at her friend’s cheeks, the relaxed pout of her mouth, the way her lashes swung up at her smooth eyelids, rapid with the movement of her dreaming, Sophie thought that Ella’s beauty had pulled ahead, was in the lead, would almost certainly win.

Ella’s eyes shot open, and Sophie felt like she’d been caught doing something creepy, staring at her friend while she was gone. “What?” Ella demanded.

“Nothing,” Sophie said, nervously. “You were out for a while, I was just checking on you.”

“How long was I out for?”

“Like, five minutes, maybe ten,” Sophie lied.

Ella thought about it, then shrugged in the dirt. “I felt like I was out for five or ten hours,” she said.

“Nothing. Maybe a dog. Yeah, a dog, a big sweet dog. God, I want a dog so bad,” Ella mourned. “My mother is such a cat person, she’ll never let me get one.” Ella closed her eyes, trying to get back to the fading sensation of some soul mate dream-dog. “It felt so nice to be next to it!”

The thing about playing pass-out was it felt so nice to be next to whatever was in your dream. Once Sophie had gone under and had a vision of a kitchen table. She came out of it filled with a tender, almost mystical affection for the furniture. It was the weirdest thing. But Sophie could see her friend getting a little hooked on the dream dog. At least she hadn’t had a vision of the beach boy, Sophie thought. That would for sure be unbearable.

“Go,” Ella said to Sophie, arranging herself on the ground. “I got you.”

Sophie resisted laughing as she began to pant and huff. Her hair did not cascade to the ground like Ella’s; she felt loose strands catch and bunch around the snarls, like seaweed caught on a rock. Her heavy breaths puffed the dust of the ground back up into her face. She sat back on her heels and held her breath, gripping the edges of her throat tightly. She felt it in her face first, a hot tingle. Next in her hands, they seemed to disintegrate, atom by atom vanishing with a lovely shimmer, followed by the rest of her body, buzzing and gone. Sophie was faintly aware of Ella’s hands on her, laying her down. She was in a fluid place, slow and liquid, a cave perhaps. She was underwater. Things floated around her slowly, things too dark to see, but before her eyes one simple thing glowed, a starfish trapped in a hunk of sea glass illuminating the bare chest of a wild-haired mermaid. The sea glass cast a pale blue light, giving the fish-belly-white skin of the mermaid a sickly fluoresence.

Sophie thought her hair had problems. The creature’s inky mane hung suspended in the water around her head. Tangles unraveled into long, tough locks, only to join once more in a round weave of snarl, snarls stuck with slimy ropes of seaweed, with fragments of seashells and urchin shells and the curving, fragile bones of fish. Her endless hair floated out past her tail, which was a great and muscled thing, shining in places and dull in places, sometimes healthy and sometimes looking like a fish kept in a neglected aquarium, its body coming off itself in ghostly tendrils.

In her vision, Sophie pulled her twin jewel out from her shirt, the seashell buried in the frosted, ancient glass, and showed it to the mermaid. And the mermaid opened her mouth and spoke inside the water.

“Yah, I know,” she said, sounding annoyed. Her words were heavy, each one sounded carved from rock. It was an old voice—not the shaky timbre of an elderly woman but old like bedrock, a hard voice, solid. “Why do you think I am doing here, anyway? I come for you.”

The current of the waters pushed the mermaid’s hair in front of her face, obscuring her. She pulled a six-pack of plastic rings from the creek bed, tore a circle free and pulled her hair through it at the top of her head, subduing a bit of the wild mane. Sophie could see more six-pack rings and other bits of garbage stuck in the mermaid’s hair, trying to control it.

“You came for me?” Sophie asked. The mermaid’s heavy accent, her struggle with English, made Sophie unsure she was hearing right. They spoke in the glow of their jewels, their faces lit but the water dim around them. Sophie was glad about that. She had come to understand that they were submerged in the creek, and what floated around them was the terrible flotsam and jetsam of Chelsea. She would be completely grossed out if not for the absolute wonder of a mermaid, or the bizarre ability to speak and breathe underwater. How was that possible? Sophie thought it was better not to question it. Of course I can breathe underwater, she thought. That’s what happens when you hang out with a mermaid.

“You have the amulet, yes?” the mermaid gestured to the jewel. “I know you are the one. Now, put it away. Do not flaunt.”

Sheepishly, Sophie dropped her amulet into her shirt, which ballooned around her in the water.

“I come all the way from Poland to be here,” the mermaid said, her voice thick with her country. “I watch over my city, and now, come to get you, who watches over my river? No one. Is unprotected. Will turn into a mess, like this place. I try and try not to come. I try to get out from it. I try to come later. No, no, no, everyone say, time is now, the girl, you do what you call—pass out?”

Sophie nodded.

“Very great way to come to you, in this special place, half-real, half-dream. Is own space. Girls find it when they come into power, at certain age.” The mermaid sighed with deep resignation. “So, was time to come for you. And here we are in this—what you call this? Not a river—”

“A creek,” Sophie offered.

“Yes. Is terrible! So skinny, like a girl that doesn’t eat. I am used to my big river, water all around me.” The mermaid spread her hands grandly, to indicate space. One hand banged up against a rusted, submerged shopping cart, the other slapped against the earthen wall of the narrow channel. Sophie noticed shining rings on the creature’s pale fingers, iridescent shards of seashells. “My back is very sore from having hunch to be in this small water,” she continued her complaint. “And the water, so dirty! But all the waters everywhere, very, very bad. I see in my journey here. One place in the ocean is so evil, a machine pours darkness into the water, pure darkness, and if it touches you, you become the darkness, you get caught in it like this—” She caught a floating tangle of hair and thrust it at Sophie. Sophie saw a hermit crab, its tiny shell imprisoned in the snarl. “You cannot move, the darkness ensnares you, you sink down down down until you die.” She shook her head. “I would think that machine is where the night comes from, except night comes from the sky and is gentle. This is something wrong.”

“It’s oil,” Sophie offered. “There was a big spill or something.” She had seen it on the news, flickering across her mother’s sleeping face.

“Well, it fucking sucks. Excuse my language, but I try to speak words you know. You know ‘fucking sucks,’ yes?”

Sophie nodded.

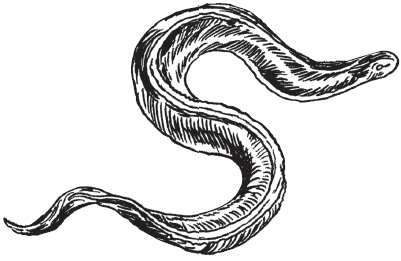

“To leave my beautiful river—I keep it very nice, I promise you. I have lived there for many, many hundreds of years and the people, they are very good to me, they put my picture on the seal of the city, even. I am—what you call—a celebrity. Parents scare your children with me. They tell them, ‘You throw trash in the river; Syrena will come and get you.’ And I do! I come in their dreams, like I am in your dream right now.” Syrena took a moment to consider herself. “I am not like the mermaids in your books and pictures, no? They are very—they are like dolls. They are pretty, but they are not real. I am real mermaid. Rusalka, river mermaid.” She bunched her hair and twisted it in a long bundle, like a baguette, pulled it over one bare shoulder. An eel poked its confused head from the garland, and the mermaid plucked it free, sent it zooming into the dark of the creek.

“That is probably bad,” she said. “Eel in your creek. Not right to have eels in this creek. But it’s so filthy, he will die before doing any harm.” The mermaid took a deep, sad breath, and coughed in a heavy sputter of bubbles. She pulled her hair in front of her mouth and hacked into the tangle. “This is like, humans smoke cigarettes? Being in this creek is like being in the smoke of eighty million cigarettes smoked all at once.”

Sophie wrinkled her face. “That sounds horrible.”

“Is fucking disgusting. That what humans say? Fucking disgusting?”

Sophie half-nodded, half-shrugged. “Certain kinds of humans,” she said.

“I was told here, this creek, where I find you—Chelsea?”

Sophie nodded.

“I was instructed—much ‘fucking sucks,’ ‘fucking disgusting.’ What else? I don’t know, put ‘fucking’ in front of much words, no? Then you understand?”

“I would understand without it,” Sophie said. “It’s sort of a—bad word.”

Sophie nodded. “I guess it is.”

“I come to you to help you fix it,” Syrena said heavily. She didn’t seem happy about it, but she didn’t seem sad either. “I have show for you. Something to feel. Will be hard. I would ask, Are you ready? But I don’t think you are, and is time for you regardless. Everything has own time, and time much bigger than us all.” The creature sighed and with her long, bony hands pushed her hair strongly from her face. The amulet lit up her sharp cheekbones; they were almost finlike, lifting from the contours of her blueish-white skin. Her clear eyes shone at Sophie and in them Sophie felt something to be trusted. But she didn’t like the sound of any of this, and began to shake herself around beneath the water.

“I’m going to wake up now,” she told the mermaid. “This has been cool, seeing a mermaid, but I’ve got to wake up before I kill my brain cells. Okay?” She tried to twist herself awake but felt the weight of the water upon her like a straight jacket, constricting her.

“Brain is fine, brain is fine,” the mermaid said dismissively. “You wake up when allowed. First, you must understand. Here.” The creature’s hands, cupped together, opened like the shell of an oyster, revealing something small and gleaming, round and pale but not an oyster.

“What is that?” Sophie asked.

“Is salt.” The mermaid smiled, a real smile now, her mouth, thin and wide, cracking into her face. The mermaid was terribly old, old as the rocks in the furrows of the deepest valley at the ocean’s bottom, but in her smile she was just a girl, a girl like Sophie, or Ella. “At start of journey, this salt as big as house! I wrap in seaweed for one day. From everywhere everyone help me—my sisters help, and fish help us, and seals, you know, everyone pitch in. And together we wait for whale shark to come, and into its mouth it goes. So big! The whale shark not like, not at all. Too salty! All along it spits and spits.” Syrena laughed, again becoming young, just for a flicker. “Slowly, the salt melt. From sea to sea we travel, it melts. The salt is not regular salt. This the salt that make the ocean.” The mermaid’s fisted hand loosened, and Sophie caught a silvery flash of the crystal in the dark.

“Two giant women, they make it far from here, at the bottom of the ocean. Women so big, if they here now, water would dribble at their feet! They are ogress. You know them? Big, big women! An ocean king take them many years ago, when they were just girls. King thought they were women already, they were so big, but no, they are just baby ogresses. Strong little babies! The king make them slaves, tell them to mine gold from the earth beneath the ocean. And they do for a little bit, because they were just babies and the digging was fun, but they grow older and become wise and they try to escape but they cannot. And so they begin to dredge salt instead of gold. So much salt! The ocean becomes full of it! The king cannot take it, he flee to some fresh water somewhere, he there still, what you call—refugee? In little bitty spring. And the ogresses keep bringing the salt to the ocean. They don’t mind, many creatures like the salt, and so they do it and do it, even now.” The mermaid smiled with the thought. “I hear story of ogresses since baby mermaid. Was something to see! Their big toe as big as your whole body. You could sleep on their toenail!” The mermaid laughed, shimmering globes of air bubbling up around her. Sophie tried to imagine a woman so big. “Ogress would let you sleep on her toe,” the mermaid continued. “They—sisters—they know all about you. You famous for them like they famous for me. Say you will need their salt, they dig out big piece for you, they say will dig you more. They say you will—make them feel better.”

Sophie liked the thought of being famous with friendly ogresses, but her concern was growing into a higher pitch of panic. This wasn’t a normal pass-out vision. It had been too long, she was too conscious, too participatory. “I don’t mean to be rude,” she said to the mermaid. “But I really think I ought to stop. To wake up or whatever.”

The mermaid ignored Sophie and moved closer. “We must begin,” she said sternly, her joy at having met the ogresses gone, her ancient face set back to steel and determination. She brought her face to Sophie’s so that her hair hung about them like a tent. Her eyes sparked brighter. It seemed that the darker the water, the more the creature’s eyes glowed, like lightning bugs were trapped in her skull, illuminating the murk. Was the mermaid good or bad? Sophie felt she was both—her badness a hardness like a rock inside her, and her goodness the light in her eyes. “I will give you feeling,” the mermaid spoke. “You ready to feel?”

Sophie laughed, a skittish hiccup that bubbled to the surface like a lone jellyfish. “I guess,” she shrugged. The mermaid placed her forehead to Sophie’s brow. How smooth it felt, like a dolphin Sophie had once touched at the aquarium. The mermaid’s fingers, long and gnarled as coral branches, cupped her cheeks, slick as seal skin. Sophie felt something like love flare inside her, and wondered if that was the feeling the mermaid was giving her, this leaping feeling of love, of excitement.

“You guess,” the mermaid said, hearing her thoughts.

“This is it?” Sophie asked with a smile.

“Not yet,” the mermaid said, moving the glowing talisman around her neck so that it clanked gently against Sophie’s. “This your feeling.”

“Oh,” Sophie giggled. The giggle was like a school of tiny silver fish bursting in the water around her face. “I’m starting to feel silly.”

“Okay, now I give you feeling,” the mermaid said. She closed her eyes like snuffing a candle, and the water grew dark around them. Her face pressed closer and the fingers on the girl’s face grew tight.

“Sophia,” the mermaid whispered. “I very sorry.”