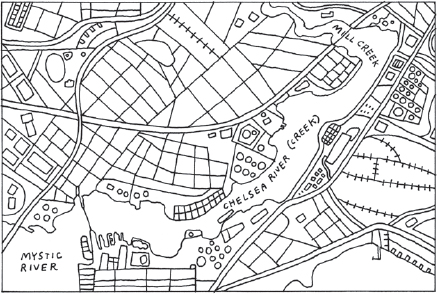

Chelsea was a city where people landed. People from other countries, people running from wars and poverty, stealing away on boats that cut through the ocean into a whole new world, or on planes, relief shaking their bodies as they rattled into the sky. People had been coming to Chelsea since before Sophie Swankowski was born, since before her mother was born. Sophie’s family came from a tiny village in Poland that nobody had ever heard of and that nobody knows of still. When they came to Chelsea, a city with trolley cars and brick houses and grand trees, they brought with them smoked sausages and doughy pierogi stuffed with soft cheese, flowered scarves for the women’s heads and necklaces made from cloth and marbles. They brought with them strong magic, the magic special to their Polish village, just as all the other immigrants brought with them the magic of their abandoned lands—Russian magic and French magic, Irish magic and Puerto Rican magic, Dominican magic and Cambodian magic, Vietnamese magic, Bosnian magic, Cuban magic, up and up through the years, always a new people spilling into the small city, always with a new magic. The fading magic was carried in the bones of the grandmothers and the great-great-aunts, the old, strange women with the funny smells that scared the children born new into Chelsea, women who ate foods that worried those children, unusual foods they didn’t sell at the supermarket, where they sold everything, all of it lined up in bright boxes. The old women ate food that made their breath smell like a long-ago time, and the children were afraid of what was back there, as they scuttled out from the smothering hugs, out to the brick and cement, the telephone poles and electrical wires, the roaring buses and the graffitied everything, busted playgrounds, a city with so much wear and tear on it, so many people with so little money coming to it for so long, the threadbare buildings and dollar stores, the railroad tracks where men slept in the tall grass, the sub shops and pizza places and the corner stores selling scratchers and cigarettes, the corner bars with no windows and men inside heaped and immobile as the cracked stools they sat upon. The children ran out into the streets and the old women thought quietly about how a place could have no magic, how their grandchildren would grow up magicless and never even know it. And the old women would shed a tear and lament the old countries they’d abandoned, longing for a land where the magic came up into their bones just from standing on its earth.

* * *

ALL OF THE magics were different, but then all of them were exactly the same. And the stories brought from the many places were all different, but then, they were all the same. And the oldest story, the silliest and most dangerous story, the saddest and most hopeful story, was the story of the girl who would bring the magic, the girl who would come to save them all.

“Save us from what?” snapped the adult children, impatient with these old women and the hocus-pocus they’d never been able to shake, even with their electricity and televisions, their blenders and flushing toilets and the million plastic gadgets they could never have imagined in their village. And the old women told them about how a girl would come and she would be a magic girl, she would twist the world we think we know and knot it into a bow, she would stop time and peer into your heart, she would take on your troubles—and yours, and yours—and they would pass through her and into the earth. The old women told them about how the girl would eat salt to stay pure and unharmed, to keep her magic sharp and crystal, and about how you would know the girl as a baby who craved salt, who ate it like sugar, enough to poison a normal child to death.

The magicless adults who had been born into this new land, into Chelsea, felt sad for the old women, who had sacrificed so much to come to this new land and seemed so disappointed in it that all they could do was make up fairy tales to comfort themselves. And the old women began to die away as old women do, their aged and magic bones buried in new earth, and no one remained to tell their stories but their stories somehow remained, a low whisper that blew off the dirty harbor, that echoed with your footsteps as you passed quickly beneath an overpass, that drifted like an aroma from a kitchen window, something familiar but strange, gone before you could grasp it. They were present at slumber parties, when girls gathered like witches at midnight, the room dark and vibrating with giddy excitement and mysterious thrill, when ghosts were talked of and pranks were played, the stories crackled in the air like static electricity, passing between the girls like sparks from fingertips: a story of a girl who could let all the sadness of the world pass right through her, and everyone would be happier for it, depressions would lift and cruelties would fade and broken people would be healed by this girl who ate salt—just stupid salt, the stuff on the kitchen table. But the old women had known that salt was a crystal, made by the earth itself, full of deep magic. Salt made everything pure, and the girl who would come and swallow the world’s troubles, bringing back a golden time, would eat great piles of salt, common table salt and magical salt from the bottom of the ocean, salt pulled from the waters of the sea and salt dug out from mines and caves.

And all across the city, that city and so many cities just like it, all around the earth, there was a sense of waiting, of biding time—though if you asked them, anyone, what they thought they were waiting for, nobody would know what you were talking about.