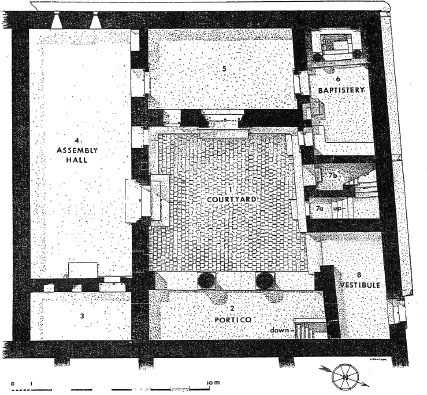

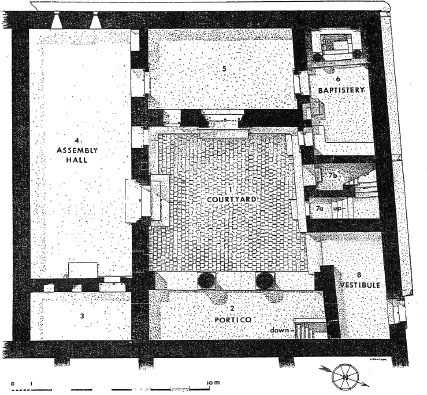

Figure 2.4 The house church at Dura-Europos

CHRISTIANS IN THE THIRD CENTURY

This chapter aims to outline some of the key features of Christianity in the period when it was still a minority religion, sometimes subject to persecution by the authorities. The opening passage presents some of the significant distinguishing features of church organisation and practices (2.1), while the second amplifies one of those features which helps to explain Christianity’s attractiveness, namely charitable work of a very practical kind (2.2). The issue of the number of Christians during the first half of the third century is raised (if not answered) by the next two items (2.3, 2.4), and that of the social profile of adherents is highlighted through the evidence presented in 2.5, 2.6 and 2.7. Gnostic teachings, an important facet of the Christian scene during the second century but exercising ongoing influence in the third, are illustrated in 2.8, before turning to pagan reactions to Christianity, first, in the form of philosophical critiques (and Christians responses) (2.9), and second, in the form of persecution. An instance of localised persecution in the 230s, and its intriguing consequences, is described in 2.10, followed by some of the evidence arising from the first empire-wide persecution during the reign of the emperor Decius in 250, including a detailed account of a martyrdom (2.11, 2.12). The chapter concludes with an important item relating to the persecution initiated by the emperor Valerian in the late 250s (2.13).

There are many indications within this material as to why Christianity proved an attractive religious option during the third century, but it leaves unanswered the important underlying question of just how successful it was during this century, before the advent of Constantine introduced an imponderable new factor into the equation. Part of the difficulty here is uncertainty about what happened during the decades after the end of the Valerianic persecution in 260. Some scholars have seen this as a period of rapid growth for the church, while others have argued that Christians still constituted only a small minority of the empire’s population by the end of the century – with the view one takes on this issue having implications for the significance of Constantine.

For discussion and further references, see Chadwick 1981; Lane Fox 1986: 585–95; Praet 1992–93; Galvao-Sobrinho 1995; Runciman 2004; Clarke 2005.

2.1 Christian organisation and activities: Tertullian Apology 39.1–6

The great north African Christian apologist Tertullian (c.160–c.240) here gives an account of the character of Christian organisation and activities at the end of the second century (c.197), with a view to rebutting common misconceptions about the group. His description makes clear the importance of communal prayer and the reading of Scripture in the life of the church (on which, see further Gamble 1995: ch. 5), the existence of disciplinary procedures, and the central role of charity. In order to make his comments accessible to non-Christians, he deliberately uses terminology that would have been familiar from the widespread common-interest associations, clubs and philosophical schools of the Roman world, while at the same time highlighting the significant ways in which the Christians differed from these non-Christian social groupings (Wilken 1984: 45–7).

(1) I will now tell you about the activities of the Christian club (Christiana factio): having proved they are not bad, I will show they are good, if I have indeed revealed the truth. We are an association (corpus) based on shared religious conviction, the unity of our way of life, and the bond of a common hope. (2) We come together in meetings and assemble to assail God with prayers as if drawn up for battle. Determination of this sort pleases God. We also pray for the emperors, for their officials and those in authority, for the well-being of the world, for peace in human affairs, for postponement of the end of the world. (3) We come together to read the divine writings, to see if the nature of the present times requires us to look there for warnings of what is to come or for explanations of what has happened. We nourish our faith with these holy words, we strengthen our hope, we consolidate our trust, and likewise we reinforce our discipline by the instilling of divine precepts. (4) In the same place there is also encouragement, chastisement, and censure in the name of God. Judgement is undertaken with great seriousness, as is appropriate among those who are confident they are in the presence of God, and it is a grave foreshadowing of the judgement to come if anyone has sinned to such an extent that they are excluded from participating in prayers, from gatherings and from all holy communion with God. (5) Older men of proven character are in charge, men who have achieved this rank not by payment, but by proof of their merit, for nothing of God’s can be bought for a price. Even if there is a money chest (arca) of sorts, it does not accumulate from payments for membership (honoraria), as though true religion were a commercial commodity. Each person deposits a modest sum once a month, or when they wish – and only if they wish and are able. For no one is forced to give, but does so voluntarily. (6) These gifts are like deposits of devotion. For the money is not spent on feasting or heavy drinking or worthless taverns, but on feeding the poor, and burying them, on boys and girls deprived of means and of parents, on elderly slaves who have outlived their usefulness, on the shipwrecked, and on any who are in the mines or on islands or in prison because, for the sake of the school of God (Dei sectae), they have become charges of the faith they profess.

2.2 Christian charity in action: Eusebius Church History 7.22.7–10

This passage – part of a letter by Dionysius, bishop of Alexandria (247–c.264) (on whom see Clarke 1998), reproduced by the church historian and bishop Eusebius (c. 260–339) – provides a graphic and striking illustration of the church’s charitable activities referred to in the previous extract – ‘probably the most potent single cause of Christian success’ (Chadwick 1967: 56). Here, Dionysius reports the responses of the Christian and pagan communities of Alexandria to a severe bout of plague in 262. From the perspective of contemporaries, the contrasting treatment of the dead would have been as significant as that of the sick. For intriguing suggestions about the wider implications of all this, see Stark 1996: ch. 4, Runciman 2004: 12–18. For Eusebius’ Church History more generally, see Johnson 2014: ch. 4.

(7) The vast majority of our brethren were, in their very great love and brotherly affection, unsparing of themselves and supportive of one another. Visiting the sick without thought of the danger to themselves, resolutely caring for them, tending them in Christ, they readily left this life with them, after contracting the disease from others, drawing the sickness onto themselves from their neighbours, and willingly partaking of their sufferings. Many also, in nursing the sick and helping them to recover, themselves died, transferring to themselves the death coming to others and giving real meaning to the common saying that only ever seems to be a polite cliché, ‘Your humble servant bids you farewell’. (8) The best of our brethren departed life in this way – some presbyters and deacons and some of the laity, greatly esteemed, so that, on account of the great devotion and strong faith it entails, this kind of death does not seem inferior to martyrdom. (9) Gathering up the bodies of the saints with open hands into their laps, they closed their eyes and shut their mouths before carrying them on their shoulders and laying them out; they clasped and embraced them, washed and dressed them in grave clothes – then before long, the same would happen to them, since those left behind were continually following those who had preceded them. (10) But the pagans (ta ethnē) behaved completely the opposite. They shunned those in the early stages of the illness, fled from their loved ones and abandoned them half-dead on the roads, and treated unburied corpses like garbage, in their efforts to avoid the spread and communication of the fatal disease – which was not easy to deflect whatever strategy they tried.

2.3 The number of Christians in third-century Rome: Eusebius Church History 6.43.11–12

How many Christians were there in the third century? The only item of statistical evidence occurs in the following passage, in which Eusebius reproduces part of a letter written by Cornelius, bishop of Rome, to Fabius, bishop of Antioch, in 251. Cornelius’ purpose in writing was to give Fabius a report on the so-called Novatian schism, which arose from Novatian’s rigorist line against Christians who lapsed during persecution, but in doing so, he provides interesting incidental detail about the numbers of various categories of individual in the church at Rome in the mid-third century. Because of the rarity of such statistics, attempts have been made to extrapolate the overall size of the church at Rome and even the approximate number of Christians in the Roman empire at this time, but there are problems in doing so. On the basis of Eusebius’ figures, Edward Gibbon ‘venture[d] to estimate the Christians at Rome at about fifty thousand’, from which he deduced that they might have constituted at most ‘a twentieth part’ of the population of the city and hence of the empire (Gibbon 1994: vol. 1, 504, 507). But ‘the guess was too high, not least because widows and the poor were strongly represented in the Church’s membership. Even if the figure is more or less right, we cannot project a total for Rome, the capital, onto other populations in the Empire. Rome was an exceptional city, a magnet for immigrants and visitors, where Christians had rapidly put down roots’ (Lane Fox 1986: 268–9). For this issue more generally, see Stark 1996: 2–12; Hopkins 1998.

(11) So this champion of the gospel [Novatian] did not know that there should be only one bishop in a catholic church where he knew full well that there are forty-six presbyters, seven deacons, seven sub-deacons, forty-two assistants (akolouthoi), fifty-two exorcists, readers and door-keepers, and more than 1500 widows and poor, all of whom the grace and charity of the Lord supports. (12) But this multitude, so necessary in the church, a number rich and increasing through the providence of God, together with the great and innumerable laity, did not turn him from such desperate and doomed action and recall him into the church.

2.4 An early Christian house church: Dura-Europos, Syria

The town of Dura-Europos on the Euphrates not only preserves much evidence relating to pagan religious practices (1.1, 1.4), it is also the site of the earliest surviving example of a Christian meeting place. The building (Figure 2.4) lies in a residential quarter of the town and is itself ‘simply a typical private house . . . modified slightly to adapt it to religious use’ (Kraeling 1967: 3). The house was built c.232–3, so its conversion to a Christian meeting place must have taken place between that date and the capture of Dura by the Persians in 256 (probably in the 240s: Kraeling 1967: 38). The two most significant rooms are the assembly hall (4) and the baptistery (6). The former was created by knocking down a wall between two smaller rooms and placing a low platform at the eastern end of the room, which could now hold perhaps sixty people (Lane Fox 1986: 269–70). The latter incorporates at its western end a basin surmounted by a heavy vaulted canopy supported by columns and the room is entirely painted, its walls decorated with Biblical scenes from both Old and New Testaments – Adam and Eve, David and Goliath, the good shepherd and his sheep, the healing of the paralytic, the woman at the well, and Jesus walking on the water (for colour pictures of these paintings, see Kraeling 1967; Grabar 1967: 69–71). By contrast, the assembly hall is undecorated, implying that ‘for the Christians of Dura the room devoted to the initiatory rite had a character and importance not shared by the Assembly Hall’ (Kraeling 1967: 40).

Further reading: Kraeling 1967; Snyder 1985: ch. 5; White 1990: ch.5; 1997: 18–24, 123–34.

Figure 2.4 The house church at Dura-Europos

Source: The Excavations at Dura-Europos, Final Report VIII, Part I: The Christian Building, edited by C.H. Kraeling (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1967), Figure 1

2.5 Christians in the imperial palace: ILCV 3332 and 3872

Another important issue besides that of numbers is the social profile of Christianity. The final item in this chapter (2.13) includes a statement implying that there were adherents of Christianity among the Roman social elite – senators and equestrians – by the 250s. The following inscriptions from Rome point to Christianity having penetrated the administrative ranks of the imperial palace rather earlier in the century, and to quite a high level in the case of the first text. Its first paragraph was inscribed on the front of a sarcophagus and presents a normal career summary without any hint of religious affiliation (the expedition from which Prosenes was returning must have been the Mesopotamian campaign of 217 in which the emperor Caracalla was killed). However, the phrase ‘received to God’ in the second paragraph, inscribed in a much less conspicuous place, has widely been interpreted as a veiled profession of Christian allegiance (for residual doubts, see Pietri 1983: 556). Such a conclusion is certainly consistent with statements by a number of Christian writers during this period (e.g., Tertullian To Scapula 4.5–6), while there is other epigraphic evidence, such as the second text below with its less ambiguous Christian references (probably from the early third century: McKechnie 1999: 438), suggesting Prosenes was by no means unique. For further discussion of the second inscription, see Clarke 1971, and for all the relevant evidence, see McKechnie 1999.

(a) ILCV 3332 (= CIL 6.8498)

[on the front of the sarcophagus] For Marcus Aurelius Prosenes, freedman of the emperors, imperial chamberlain, supervisor of the treasury, supervisor of the imperial estate, supervisor of the gladiatorial shows, supervisor of wines, appointed to the imperial administration by the deified Commodus: his freedmen had this sarcophagus adorned for their most devoted and well-deserving patron from their own resources.

[on the upper edge of the right-hand end of the sarcophagus] Prosenes was received to God (receptus ad deum), on the 5th day before the Nones of <May/July?> [3 May/July] at S<ame in Cephalle?>nia, when Praesens was consul and Extricatus consul for the second time [217], while returning to the city [of Rome] from campaign. Ampelius, his freedman, wrote this.

(b) ILCV 3872 (= CIL 6.8987)

Alexander, slave of the emperors, set up [this epitaph] while he was still alive for his dearest son, Marcus, a student at the Caput Africae school [for training imperial slaves], who was assigned to the tailors and who lived for 18 years, 8 months, and 5 days. I ask you, good brothers (boni fratres), by the one God (per unum deum), not to damage this inscription after my death.

2.6 Christians in local administration: SB 16.12497

The (damaged) papyrus from which the following passage is extracted comprises a list of individuals nominated, at some point in the first half of the third century, for liturgies in Arsinoe, a district capital in Egypt. In the context of Roman Egypt, a liturgy was a compulsory public service, which could involve anything from serving as village policeman, to collecting taxes, to being official banker for the district. Many liturgies involved financial responsibilities, so individuals nominated for such liturgies by the local authorities had to satisfy property requirements so that they could make good any shortfall out of their own pocket; needless to say, liturgies were not a very popular feature of Roman rule (Lewis 1983: 177–84; Lewis 1982). (It is clear from earlier sections of this papyrus that the damaged right-hand side of our extract listed details of each individual’s property qualification.) If the dating of this papyrus to the first half of the third century is correct (it is based on the styles of handwriting: Sijpesteijn 1980: 341), then this seemingly innocuous item of routine administration is of great significance, since it is ‘the earliest example of a Christian in an official text from Egypt’ (Van Minnen 1994: 74). It has been deduced from the two different styles of handwriting used in compiling the list that ‘a second clerk went over the list and added some personal detail about each candidate, presumably to give the reviewer of the list, his superior no doubt, some idea of the suitability of the candidate’ (Van Minnen 1994: 75). It is the final name on the list which is of interest, for Antonius Dioskoros is described as being a Christian, showing that in this period ‘Christians were at least considered for minor public offices in Egypt’ (Van Minnen 1994: 76). If the social background of the other nominees is anything to judge by, then Antonius probably came from the same milieu of ‘urban shopkeepers and craftsmen of moderate means’, though the Alexandrian origin of his father and the Roman element in his name may have given him enhanced social status; at any rate, a third official who went down the left-hand margin ranking the nominees seems to have rated him highly against the others, despite the potential disadvantage of his religious affiliation (Van Minnen 1994: 76). His family’s Alexandrian origin is also consistent with what might be expected about the manner in which Christianity spread within Egypt, namely by migration from the capital up the Nile valley (Van Minnen 1994: 76).

For responsibility for the water-reservoir and the fountains of the district capital < . . . >

4th [1st hand] Sarapammon, also known as Arios, son of Nilos, son of Zoilos, from < . . . >

[2nd hand] He is the < . . . > of the new landowner < . . . >

8th [1st hand] Isidoros, also known as Herakleides, son of Heron, son of Socrates < . . . >

[2nd hand] He is a good man and a manufacturer of oil in < . . . >

5th [1st hand] Theodoros, son of Isidoros, son of Ischyrion, from < . . . >

[2nd hand] He is the son of the Isidorus who lives in the < . . . >

7th [1st hand] Ammonios, son of Magnus, also known as Menouthes, from the gymnasium quarter < . . . >

[2nd hand] Ammonios is a chatterbox and a labourer < . . . >

2nd [1st hand] Antonius Dioskoros, son of Horigenes from Alexandria < . . . >

[2nd hand] Dioskoros is a Christian < . . . >

2.7 Women in the church: Porphyry Against the Christians fr. 97 (= Jerome Commentary on Isaiah 3.12)

In addition to philosophical works such as On Abstinence (cf. 1.13), the Neoplatonic philosopher Porphyry (234–c.305) wrote a work entitled Against the Christians (debate continues as to whether it was written in the 270s or c.300: Croke 1984–5; Barnes 1994b). As a result of official book burnings by Christian emperors in the fourth and fifth centuries, however, it survives only in the form of quotations by later writers, usually Christian authors seeking to refute Porphyry’s arguments. In this case, the fourth-century scholar Jerome refers to one of Porphyry’s claims in the course of commenting on a passage from Isaiah 3.12, ‘My people have been robbed by their own tax-collectors and are ruled by women.’ Porphyry is obviously not an unbiased source, but his jibe is nevertheless evidence for the prominence of women in the third-century church, and particularly women of high social status.

Further reading: Meredith 1980: 1123–37; Wilken 1984: ch. 6; Demarolle 1970; Eck 1971: 399–401.

Let us therefore also take care that we are not extortioners among our people, that, as the godless Porphyry claimed, married ladies (matronae) and [other] women do not constitute our ruling body (senatus), exercising authority in church congregations, and that the prejudice of women does not determine priestly rank.

2.8 An example of Gnostic literature: extracts from The Gospel of Philip (Nag Hammadi Codex II, 3)

‘Gnostics’ is the catch-all term that has been used by modern scholars for a range of early Christian groups who placed particular emphasis on the importance of special knowledge (gnōsis) as the key to salvation. This knowledge typically included a dualistic understanding of the universe which set a perfect spiritual world against an imperfect material world (complete with complex mythologies to explain how this came about), with the human goal being to reunite the spiritual element within with the perfect spiritual world. Gnosticism has provoked widely divergent views from modern scholars, ranging from those who see it as the predominant trend within Christianity for much of the second century, to those who regard it as diverging so far from fundamental Christian tenets that it must be regarded as essentially a separate religion. All would agree, however, that modern understanding of Gnosticism, previously reliant primarily on information derived from anti-Gnostic writers in antiquity, has been revolutionised by the discovery in 1945, at Nag Hammadi in southern Egypt, of a major cache of texts written by Gnostics themselves. Many of the Nag Hammadi texts are fourth-century Coptic translations of earlier Greek works, including the example below, originally written ‘perhaps as late as the second half of the third century’ (Isenberg 1988: 141). Despite its title, the Gospel of Philip does not present a narrative of the life of Jesus, but rather a somewhat disjointed collection of sayings. The extracts chosen here reflect various aspects of Gnostic thought, more specifically the strand associated with one of the most influential Gnostic exegetes, Valentinus, active in both Egypt and Italy in the mid-second century. The Gospel of Philip itself was not written by Valentinus, but reflects the ongoing influence of his ideas. It is noteworthy that, while New Testament scriptures are quoted (77), the designation ‘Christians’ is used (74), and there is reference to rites of baptism and eucharist (67), yet it is also asserted that the creation of the world was a mistake (75). An ascetic tendency is also evident in the reference to virgins (69), at odds with the frequent portrayal of Gnostics as libertarians by anti-Gnostic contemporaries. The literature on Gnosticism is vast: for general discussions, see Rudolph 1990; Filoramo 1990; Pagels 1979; Pearson 1990; McKechnie 1996; for specific treatments of the Gospel of Philip, see Segelberg 1960, 1983; Pagels 1991.

(67) . . . Truth did not come into the world naked, but it came in types and images. The world will not receive truth in any other way. There is a rebirth and an image of rebirth. It is certainly necessary to be born again through the image. Which one? Resurrection. The image must rise again through the image. The bridal chamber and the image must enter through the image into the truth: this is the restoration. . . .

The Lord <did> everything in a mystery, a baptism and a chrism and a eucharist and a redemption and a bridal chamber. . . .

(68) . . . When Eve was still in Adam death did not exist. When she was separated from him death came into being. If he enters again and attains his former self, death will be no more. . . .

(69) A bridal chamber is not for the animals, nor is it for the slaves, nor for defiled women; but it is for free men and virgins.

Through the holy spirit we are indeed begotten again, but we are begotten through Christ in the two. We are anointed through the spirit. When we were begotten we were united. None can see himself either in water or in a mirror without light. Nor again can you see in light without water or mirror. For this reason it is fitting to baptize in the two, in the light and the water. Now the light is the chrism. . . .

(70) . . . If the woman had not separated from the man, she should not die with the man. His separation became the beginning of death. Because of this Christ came to repair the separation which was from the beginning and again unite the two, and to give life to those who died as a result of the separation and unite them. But the woman is united to her husband in the bridal chamber. Indeed those who have united in the bridal chamber will no longer be separated. Thus Eve separated from Adam because it was not in the bridal chamber that she united with him. . . .

(74) . . . The chrism is superior to baptism, for it is from the word ‘chrism’ that we have been called ‘Christians’, certainly not because of the word ‘baptism’. And it is because of the chrism that ‘the Christ’ has his name. For the father anointed the son, and the son anointed the apostles, and the apostles anointed us. He who has been anointed possesses everything. He possesses the resurrection, the light, the cross, the holy spirit. The father gave him this in the bridal chamber; he merely accepted <the gift>. The father was in the son and the son was in the father. This is <the> kingdom of heaven. . . .

(75) . . . The world came about through a mistake. For he who created it wanted to create it imperishable and immortal. He fell short of attaining his desire. For the world never was imperishable, nor, for that matter, was he who made the world. . . .

(77) . . . He who has knowledge of the truth is a free man, but the free man does not sin, for ‘he who sins is the slave of sin’ [Jn. 8.34]. Truth is the mother, knowledge the father. Those who think that sinning does not apply to them are called ‘free’ by the world. ‘Knowledge’ of the truth merely ‘makes such people arrogant’, which is what the words ‘it makes men free’ mean. It even gives them a sense of superiority over the whole world. But ‘love builds up’ [1 Cor. 8.1]. In fact, he who is really free through knowledge is a slave because of love for those who have not yet been able to attain to the freedom of knowledge. Knowledge makes them capable of becoming free. . . .

(tr. W.W. Isenberg)

2.9 Christian responses to pagan criticisms: Origen Against Celsus 5.25, 35, 8.73, 75

Origen (c.185–c. 255) was a leading Christian intellectual and theologian of the third century. In his youth, he studied philosophy in his native city of Alexandria, where his teacher may have been the man who also taught the Neoplatonic philosopher Plotinus. One of the best-known works in Origen’s prodigious output is his Against Celsus, probably written in the late 240s, in which he responded to the critique of Christianity contained in a work entitled The True Doctrine by a certain Celsus, probably written in the late second century (there is much uncertainty and debate about Celsus’ identity). In order to answer Celsus’ criticisms, Origen quotes extensively from The True Doctrine, so that in addition to being a good example of Christian apologetic literature, the Against Celsus also provides particularly clear insights into why Christianity was a cause of concern for a well-educated pagan in this period. The excerpts presented here highlight Celsus’ worries about Christianity’s apparent indifference, first, to tradition, and second, to public service, whether in the army or civil administration. (The first also has interesting implications for pagan attitudes to Jews.) Origen’s responses are of interest, in the first case, for his use of philosophical argument to highlight the inconsistencies in Celsus’ argument, and on the second issue, for what they reveal about one possible approach to a matter of central and increasing importance for Christians (cf. 12.1 and Tomlin 1998: 23–5 for Christians in the army).

Further reading: Chadwick 1953: Introduction; Wilken 1984: ch. 5.

(25) Let us also look at Celsus’ next passage which reads as follows: ‘Now the Jews became an individual nation, and made laws according to the custom of their country; and they maintain laws among themselves at the present day, and observe worship which may be very peculiar, but is at least traditional. In this respect they behave like the rest of mankind, because each nation follows its traditional customs, whatever kind may happen to be established. This situation seems to have come to pass not only because it came into the head of different people to think differently and because it is necessary to preserve established social conventions, but also because it is probable that from the beginning the different parts of the earth were allotted to different [divine] overseers, and are governed in this way by having been divided between certain authorities. In fact, the practices done by each nation are right when they are done in the way that pleases the overseers; and it is impious to abandon the customs which have existed in each locality from the beginning’. . . .

5. (35) From these facts the argument seems to lead Celsus to the conclusion that all men ought to live according to their traditional customs and should not be criticized for this; but that since the Christians have forsaken their traditional laws and are not one individual nation like the Jews they are to be criticized for agreeing to the teaching of Jesus. Let him tell us, then, whether philosophers who teach men not to be superstitious would be right in abandoning the traditional customs, so that they even eat of things forbidden in their own countries, or would they act contrary to moral principle in so doing? For reason persuades them not to busy themselves about images and statues or even about the created things of God, but to ascend above them and to present the soul to the Creator. If Celsus or those who approve of his views were to try to defend the view which he has set forth by saying that one who has read philosophy would also observe the traditional customs, that implies that philosophers, for example, among the Egyptians would become quite ridiculous if they took care not to eat onion in order to observe traditional customs or abstained from certain parts of the body such as the head and shoulders in order not to break the traditions handed down to them by their fathers. And I have not yet said anything of those Egyptians who shiver with fear at the trivial physical experience of flatulence. If one of their sort became a philosopher and were to keep the traditional customs, he would be a ridiculous philosopher because he would be acting unphilosophically. . . .

8. (73) Then Celsus next exhorts us to ‘help the emperor with all our power, and co-operate with him in what is right, and fight for him, and be fellow-soldiers if he presses for this, and fellow-generals with him’. We may reply to this that at appropriate times we render to the emperors divine help, if I may so say, by taking up even the whole armour of God [Eph. 6.11]. And this we do in obedience to the apostolic utterance which says, ‘I exhort you, therefore, first to make prayers, supplications, intercessions, and thanksgivings for all men, for emperors, and all that are in authority’ [1 Tim. 2.1–2]. Indeed, the more pious a man is, the more effective he is in helping the emperors – more so than the soldiers who go into the lines and kill all the enemy troops they can. . . .

8. (75) Celsus exhorts us also to ‘accept public office in our country if it is necessary to do this for the sake of the preservation of the laws and of piety’. . . . If Christians do avoid these responsibilities, it is not with the motive of shirking the public services of life. But they keep themselves for a more divine and necessary service in the church of God for the sake of the salvation of men. Here it is both necessary and right for them to be leaders and to be concerned about all men, both those who are within the Church, that they may live better every day, and those who appear to be outside it, that they may become familiar with the sacred words and acts of worship. . . . .

(tr. H. Chadwick)

2.10 Localised persecution and church divisions: Cyprian Letter 75.10

This passage, part of a letter written in 256 by Firmilian, bishop of Cappadocian Caesarea (early 230s–268), to Cyprian, bishop of Carthage, on the general subject of baptismal procedure, describes events in Cappadocia more than twenty years earlier, in 235. It is of interest, first, because it presents an example of the sort of localised persecution of Christians which was characteristic of the church’s experience prior to the mid-third century when the emperor Decius initiated the first empire-wide persecution (see below), and shows the sort of circumstances which might prompt such an occurrence. Second, it provides an intriguing example of ecclesiastical authorities having to deal with a serious internal challenge – in this instance, a female prophetess. Certain features are reminiscent of the so-called Montanist movement of the second half of the second century, known for the high-profile role of female prophetesses and for designating their centre in western Anatolia as the ‘New Jerusalem’: ‘It is possible the extraordinary distress caused by a series of natural disasters [in 235] led to the resurgence of this eschatological movement’ (Elm 1994: 32).

Further reading: Clarke 1984–89: vol. 4, 246–52, 263–8.

(1) I want to tell you the story of what happened among us, relevant as it is to this subject. About twenty years ago in the period after the emperor Alexander [Severus], many adversities and misfortunes occurred, both to everyone in general and to Christians in particular. There were numerous frequent earthquakes throughout both Cappadocia and Pontus which destroyed many buildings; some towns were even swallowed up by cracks opening in the ground and taken down into the depths. As a result of this, a serious persecution of the Christian name took place against us. Arising suddenly after the previous lengthy period of peace, it was an unexpected and unfamiliar calamity and so disconcerted our people all the more severely. (2) Caught up in this confusion, the faithful fled hither and thither in fear of persecution, departing from their homelands and crossing into neighbouring regions (such movement was an option since this persecution was localised, not universal). Suddenly a woman came to the fore who presented herself as a prophetess experiencing states of ecstasy and acted as though filled with the Holy Spirit. But she was so overwhelmed by the onset of the leading demons that for a long time she seduced and deceived the brethren, performing certain monstrous marvels, and promising to make the earth quake. Not that the demon had the power to cause earthquakes or was able to upset the elements by its own strength; rather, that evil spirit, being able to foresee that an earthquake was about to happen, sometimes pretended that it was going to bring about what it saw would happen anyway.

(3) By these deceptions and displays, he gained control over the minds of some individuals, who obeyed him and followed him wherever he commanded and led. He also made the woman go barefooted through the freezing snow in the harsh winter, without her being troubled or harmed in any way by the outing. She also said she was in a hurry to get to Judaea and Jerusalem, pretending that it was from there that she had come. (4) The demon also deceived one of the presbyters, of rural origin, and another man, a deacon, so that they had illicit relations with this same woman, as was revealed a little later. For suddenly there appeared before him one of the exorcists, a man of proven character who always conducted himself properly with respect to church teaching. After being encouraged and stirred to action by several of the brethren who were themselves strong and praiseworthy in their faith, he set himself against that evil spirit to subdue it. By subtle deceit, the demon had even foretold shortly beforehand that an unbelieving assailant would come against him. But inspired by the grace of God, that exorcist resisted steadfastly and showed that that spirit which had previously been thought holy was in fact very evil.

(5) And in fact that woman who was already influenced by the deceits and tricks of the demons to deceive the faithful in many ways even dared often to do this (among the other things by which she misled many): she would pretend to sanctify the bread with a not unrespectable invocation and celebrate the eucharist, and she would offer the sacrifice to the Lord not without reciting the customary eucharistic prayer, and she would also baptise many, using the traditional and authentic words of enquiry, so that in no way did she appear to be at odds with church requirements.

2.11 Certificates of sacrifice from the Decian persecution: P. Mich. 3.157 and Wilcken no. 125

The following papyri are two of many examples of so-called libelli or certificates of sacrifice generated by the persecution which the emperor Decius initiated in late 249/early 250 (a total of forty-six have been recovered to date: Knipfing 1923 assembled forty-one; for details of a further four, see Horsley 1982: 181, to which can now be added P. Oxy. 3929, published in 1991). The immediate purpose of the certificates is clear – to prove that individuals had publicly sacrificed – but there is some uncertainty as to who was required to obtain them. The traditional view has been that all inhabitants of the empire had to have certificates (for a recent restatement, see Clarke 1984–9: vol. 1, 21–39; cf. also the introductory comments of J.R. Rea to P. Oxy. 3929, drawing (tentative) comparisons between the numbers of surviving certificates and census returns), but doubts have been raised about this. It has been observed that administering such a process for all inhabitants of the empire would have been ‘a bureaucratic nightmare’ (Lane Fox 1986: 455). Furthermore, all the surviving libelli with dates fall in June/July 250 – six months after the start of the persecution – and there is no reference to libelli in other contemporary sources before May 250 (lack of any reference to them in the Martyrdom of Pionius (2.12), which occurred during February/March 250, may be particularly significant (Lane Fox 1986: 754 n. 20), though it has also been noted that the actions required of Pionius are consistent with the libelli (Robert 1994: 53)). Given all this, a two-phase persecution has been suggested: the general requirement to sacrifice was published in late 249/early 250 (Clarke 1984–89: vol. 1, 25–6 for the date), but only when it became clear, after some months, that many Christians were not doing so were the libelli introduced as a way of monitoring the adherence of those suspected of non-compliance (Keresztes 1975: 778; Lane Fox 1986: 456). However, this alternative scenario is not without its problems. The six-month time-lag is not necessarily decisive in the light of the notorious slowness of imperial communications, and the second libellus translated below presents a particular difficulty, since it seems unlikely that suspicion can have attached to a pagan priestess. This difficulty has in turn prompted speculation that Aurelia Ammonous may have been ‘a secret Christian, just as weak as the others who availed themselves of libelli without actually having to sacrifice’ (Keresztes 1975: 777) or ‘may have had Christians in her family or a Christian phase in her earlier life’ (Lane Fox 1986: 456), but it is not clear that either of these suggestions resolves the problem satisfactorily.

More generally, the certificates are of course a reminder of the importance of sacrifice in pagan cult. Moreover, a high proportion of women is represented in the surviving certificates, consistent with what is known about Christianity’s social catchment in its early centuries (Lane Fox 1986: 456). With regard to the specific detail in the libelli below, Theadelphia is a village in the Arsinoite district, from where the largest number have been recovered. The Moeris quarter was an area within the district-capital of Arsinoe, while Petesouchos was the local manifestation of the crocodile deity widely revered in this area of Egypt. The initial number in the second papyrus is assumed to have been added for filing purposes; other libelli survive in duplicate, so it is likely that one was kept by officials for their records, while a copy was retained by the individual as proof.

(a) P. Mich. 3.157

To those appointed to oversee the sacrifices, from Aurelius Sakis, from the village of Theoxenis, with his children Aion and Heras, staying in the village of Theadelphia. We have always sacrificed to the gods and now too in your presence in accordance with the decree we have offered sacrifice and we have poured a libation and we have eaten of the sacrificial offering and we ask you to undersign. May you continue to prosper.

[2nd hand] We, Aurelius Serenus and Aurelius Hermas, saw you sacrificing.

[1st hand] The Year 1 of the Emperor Caesar Gaius Messius Quintus Trajan Decius, devout, blessed, Augustus, Pauni 23 [17 June 250].

(b) Wilcken no. 125

433: To those appointed to oversee the sacrifices, from Aurelia Ammonous, daughter of Mystos, of the Moeris quarter, priestess of the great, mighty and everliving god Petesouchos and of the gods in the Moeris [quarter]. I have always sacrificed to the gods throughout my life, and now again in accordance with the edict and in your presence, I have offered sacrifice and I have poured a libation and I have eaten of the sacrificial offering, and I ask [you] to undersign< . . . .>

2.12 A martyrdom during the Decian persecution: The Martyrdom of Pionius

Among the surviving accounts of Christian martyrs, one of the best known and most interesting is that of a presbyter from Smyrna in Asia Minor named Pionius, who was executed during the persecution initiated by the emperor Decius (249–51). The fact that a magisterial new edition of this account by the famous epigrapher and classical scholar, Louis Robert, has recently been (posthumously) published gives added reason to include it in this collection. Martyr acts are notoriously prone to elaboration and interpolation by subsequent ‘editors’ keen to enhance their edificatory value, but Robert argues that archaeological, epigraphic and numismatic evidence from Smyrna confirms the authenticity of this account, even proposing that much of it derives from an eyewitness of the events reported (Robert 1994: 1–9). In addition to its obvious value for understanding the process of arrest, trial and execution, the account contains many other cardinal points of interest, among which are Pionius’ good education and the implications of this for the social make-up of the Christian community in Smyrna, the way in which the Jewish community of Smyrna features so prominently, and the fact that Pionius had previously travelled to Palestine (cf. 16.1–2). For detailed discussion and commentary, see Robert 1994 (in French) and Lane Fox 1986: 250–92. Among points of detail, the significance of the term ‘grand sabbath’ remains a matter for debate (Lane Fox 1986: 486–7; Robert 1994: 50; Bowersock 1995: 82–4), while the two goddesses Nemeseis (the plural form of Nemesis) were the tutelary deities of the city of Smyrna (Robert 1994: 65). Due to constraints of space, a few chapters have been omitted – the opening one, ch. 6 in which Pionius has an exchange with a merchant, and the second and longer of Pionius’ two speeches (12.3–14.15).

2. On the second day of the sixth month [23 February 250], at the beginning of the ‘grand sabbath’, on the anniversary of the blessed martyr Polycarp, in the time of the persecution of Decius, there were arrested Pionius, presbyter, Sabina, confessor, Asclepiades, Macedonia, and Limnus, a presbyter of the catholic church. (2) Now on the eve of the anniversary of Polycarp, Pionius foresaw that they were to be arrested on that day. (3) He was with Sabina and Asclepiades, fasting, when he foresaw that they were to be arrested the following day, so he took three woven cords and fastened them around his own neck and those of Sabina and of Asclepiades, and they waited in the house. (4) He did this so that when they were arrested no one should suppose that they were being led away, like the rest, to partake of the defiled meats, but so that all would know that they had decided to be taken immediately to prison.

3. When, on the day of the sabbath, they had prayed and taken the consecrated bread and the water, the temple warden (neokoros) Polemon came for them, together with the others assigned to search out the Christians and drag them away to sacrifice and partake of the defiled meats. (2) And the temple warden said, ‘You know, of course, of the emperor’s edict commanding you to sacrifice to the gods.’ (3) And Pionius said, ‘We know the commandments of God, which require that we worship him alone.’ (4) Polemon said, ‘In any case, come to the main square (agora) and there you will obey.’ Both Sabina and Asclepiades said, ‘We obey the living God.’ (5) Then they took them away without having to use force. And on the way, everyone saw that they bore cords, and as happens when there is something unusual to be seen, a crowd quickly gathered, pressing on one another. (6) When they reached the main square, at the eastern portico, by the double entrance, the whole area and the upper stories of the porticoes were full of Greeks and Jews, and of women also; for they were on holiday, because it was the ‘grand sabbath’. (7) They climbed up on the benches and booths to watch.

4. They placed them in the middle, and Polemon said, ‘It is a good idea, Pionius, for you to obey like everyone else and sacrifice, and thereby avoid punishment.’ (2) Then holding out his hand, Pionius, with a radiant face, spoke in his defence as follows: ‘You men who pride yourselves on the beauty of Smyrna, who glory in Homer, son of the [River] Meles, as you say, and those of the Jews who are present among you, listen to me for a moment while I speak to you. (3) For I understand that you laugh and rejoice at those who abandon the faith, and find their failure amusing, namely when they offer sacrifice of their own free will. (4) But you Greeks ought to pay attention to your master (didaskalos) Homer, who warns you that it is not right to pride yourselves on those who die [Odyssey 22.412]. (5) As for you Jews, Moses gives this command: “If you see your enemy’s donkey sink under its burden, don’t pass by but go and help it up” [Ex. 23.5, Deut. 22.4]. (6) You should likewise give heed to Solomon: “If your enemy stumbles”, he says, “don’t rejoice, and don’t be glad at his downfall” [Prov. 24.17]. (7) For out of obedience to my master (didaskalos) I prefer to die rather than disobey his teaching and I am engaging in the contest so as not to abandon what I first learned and then taught. (8) Whom do the Jews mock mercilessly? Even if we are their enemies, as they say, we are humans and, what’s more, are mistreated. (9) They say that we have opportunities to speak freely. Maybe so, but whom have we mistreated? Whom have we killed? Whom have we persecuted? Whom have we forced to worship idols? (10) Do they think that their wrongdoings are the same as those now being done by some out of human fear? But there is a big difference between wrongdoings done willingly and those done against one’s will. (11) For who forced the Jews to worship Beelphegor and eat sacrifices to the dead [Ps. 106.28]? or to fornicate with the daughters of other peoples [Num. 25.1 etc.]? to burn their sons and daughters before idols [Num. 14.27 etc.]? to murmur against God and speak against Moses [Ex. 6.2–3]? to be ungrateful for blessings? to return in their hearts to Egypt? to say to Aaron when Moses had gone up to receive the law, “Make gods for us and fashion the calf” [Ex. 32.1ff.]? – and all the other things they did. (12) For they can deceive you. But let them read you the Book of Judges, of Kings, of Exodus and all those where they are put to shame. (13) But do they ask why some came forward to sacrifice without being forced, and do they condemn all Christians on account of them? (14) Think of the present situation as being like a threshing floor: which forms the larger pile, the chaff or the grain? When the farmer comes to clear the threshing floor with his winnowing fan, the chaff, being light, is easily carried away by the movement of the air, but the grain remains there. (15) Consider also the net which is cast into the sea: not everything it catches is useful. So it is with the present situation. (16) How then do you wish us to suffer these things – as those who have done right or as wrongdoers? If as wrongdoers, how will you who, by your own deeds, are also proven to be wrongdoers not be subject to the same punishments? But if as those who have done right, what hope do you have when the righteous suffer? “For if the righteous man is scarcely saved, where will the impious and sinner appear?” [1 Pet. 4.18] (17) For judgement is hanging over the world, of which we are convinced by many considerations. (18) I have travelled abroad and been throughout the whole land of Judaea; I have crossed the Jordan and seen the land which testifies, even to this day, to the divine anger it has experienced because of the sins of its inhabitants, who killed foreigners and drove them out with violence. (19) I have seen the smoke rising from it even to this day and the land reduced to ashes by fire, unproductive and waterless. (20) I have also seen the Dead Sea, whose water has changed and lost its natural powers through fear of God and is unable to support life; anyone who jumps into it is pushed out upwards by the water which is unable to retain a human body – for it does not want to receive a human, to avoid being punished again on account of a human. (21) I am talking about places a long distance from you. But you yourselves see and talk about the land of the Ten Cities in Lydia, burnt by fire and lying exposed even to this day as an example for the sacrilegious – fire which bursts forth from Etna and Sicily and also from Lycia. (22) If this is also distant for you, think about your familiarity with hot water, I mean the sort which gushes out of the ground, and consider where it is warmed and heated if it does not issue from an underground fire. (23) Think also about the partial conflagrations and the floods, under Deucalion according to you and under Noah according to us: they were partial so that from the parts one might understand the totality. (24) This is why we testify to you about the coming judgement of God by fire through his Word, Jesus Christ. And because of this, we do not worship your so-called gods and we do not bow down before the golden image [Dan. 3.18].’

5. Pionius said these and many other things, and did not fall silent for a long time; the temple warden with his attendants and the whole crowd strained their ears to listen, and the silence was such that no one even whispered. (2) While Pionius was saying again, ‘We do not worship your gods and we do not bow down before the golden image’, they were led into the open air, into the middle, and some of those who frequented the main square, together with Polemon, surrounded them, earnestly entreating them and saying, (3) ‘Listen to us, Pionius, because we love you and you deserve to live for many reasons, because of your character and your reasonableness. It is good to be alive and to see this light’, and a great many other such things. (4) But he said to them: ‘I agree that it is good to be alive, but that which we desire is even better. Yes, the light, but the true light. (5) Yes, indeed, all these things are good. We do not have a liking for death, nor do we despise the works of God and seek to flee them. But it is the superiority of other great blessings which makes us disregard these, which are snares.’ [In ch. 6, Pionius has a brief exchange with a merchant named Alexander.]

7. When the people wanted to hold an assembly in the theatre in order to hear more there, some men, concerned on behalf of the city general (stratēgos), went to the temple warden Polemon and said, ‘Do not allow him to speak, lest they go into the theatre and there is an uproar and an inquiry concerning the bread.’ (2) When he heard this, Polemon said, ‘Pionius, if you do not wish to sacrifice, at least come to the temple of the two goddesses Nemeseis.’ Pionius replied, ‘But it will not do your idols any good if we go there.’ (3) Polemon said, ‘Do as we say, Pionius.’ Pionius replied, ‘Would that I could persuade you to become Christians.’ (4) But laughing loudly, the men said, ‘You cannot make us burn alive!’ Pionius said, ‘It is much worse to burn after you have died!’ (5) When Sabina smiled at this, the temple warden and his assistants said, ‘You laugh?’ She replied, ‘If God wishes it, yes; for we are Christians. Whoever trusts in Christ will laugh unhesitatingly with everlasting joy.’ (6) They said to her, ‘You are going to undergo something you won’t like: for women who do not sacrifice are put in the brothel.’ But she said, ‘The holy God will look after me in this.’

8. Polemon spoke to Pionius again, ‘Listen to us, Pionius.’ Pionius replied, ‘You have instructions to persuade or to punish; you are not persuading us, so punish us.’ (2) Then the temple warden began the formal enquiry, saying, ‘Sacrifice, Pionius.’ Pionius replied, ‘I am a Christian.’ (3) Polemon said, ‘Which god do you worship?’ Pionius replied, ‘The all powerful God who made the heavens and the earth and all that is in them including all of us, who abundantly provides us with everything and whom we know through Christ his Word.’ (4) Polemon said, ‘Then at least sacrifice to the emperor.’ Pionius replied, ‘I will not sacrifice to a man, for I am a Christian.’

9. Then he continued the enquiry with a written report, saying: ‘What is your name?’ The shorthand writer (notarios) wrote down everything. Reply: ‘Pionius’. (2) Polemon said, ‘Are you a Christian?’ Pionius said, ‘I am.’ Polemon the temple warden said, ‘From which church?’ Reply: ‘Catholic – for there is no other before Christ.’ (3) Then he came to Sabina. Pionius had forewarned her, ‘Call yourself Theodota’, so that she did not, on account of her name, fall again into the hands of the lawless Politta who had been her mistress. (4) For in the time of Gordian [emperor, 238–44], when she had wished to make Sabina change her belief, she had shackled her and banished her to the mountains, where she had received food from the brethren in secret; later a great effort had been made to free her both from Politta and from the chains, and she lived most of the time with Pionius and was arrested in this persecution. (5) Polemon then questioned her, ‘What is your name?’ She replied, ‘Theodota.’ He said, ‘Are you a Christian?’ She said, ‘Yes, I am a Christian.’ (6) Polemon said, ‘From which church?’ Sabina said, ‘The catholic.’ Polemon said, ‘Whom do you serve?’ Sabina said, ‘The all powerful God who made the heavens and the earth and all of us, and whom we know through his Word Jesus Christ.’ (7) Then he proceeded to question Asclepiades: ‘What is your name?’ He said, ‘Asclepiades.’ Polemon said, ‘Are you a Christian?’ Asclepiades said, ‘Yes.’ (8) Polemon said, ‘From which church?’ Asclepiades said, ‘The catholic.’ Polemon said, ‘Whom do you serve?’ Asclepiades said, ‘The Christ Jesus’. (9) Polemon said, ‘Is this a different one?’ Asclepiades said, ‘No, he is the same as the others have stated.’

10. After these exchanges they were led off to the prison, followed by a great crowd, sufficient to fill the main square. (2) And some commented on Pionius, saying ‘How is that he who has always been so pale now has so radiant a face?’ (3) As Sabina was holding on to him by his cloak because of the buffeting of the crowd, some were saying in mockery, ‘Look, she is afraid of being separated from her wet-nurse!’ (4) One man shouted, ‘If they will not sacrifice, they should be punished!’ Polemon replied, ‘But we do not have before us the symbols of imperial authority (fasces) that give us the power to punish.’ (5) Another said, ‘Look, a midget is going to sacrifice!’ He was speaking of our companion Asclepiades. (6) Pionius replied, ‘You are lying, for he is not doing that.’ Others said, ‘Such and such has sacrificed.’ Pionius replied, ‘Each person makes their own choice. What has this to do with me? My name is Pionius.’ (7) Others said, ‘Such discipline!’ and, ‘Indeed, it is so!’ Pionius said, ‘Recognise rather the discipline of the famines, deaths and other calamities by which you have been tested.’ (8) Someone said to him, ‘But you too went hungry with us.’ Pionius replied, ‘I did so with hope in God.’

11. After having said these things with difficulty – they were being pressed by the crowd to the point of suffocation – they were thrown into the prison and delivered to the guards. (2) On entering they found imprisoned there a presbyter of the catholic church by the name of Limnus, and also a woman, Macedonia, from the village of Karina, and an adherent of the sect of the Phrygians [i.e., Montanists (cf. 2.10)] by the name of Eutychianus. (3) While they were together, those in charge of the prison realised that those with Pionius did not accept the gifts brought for them by the faithful. For Pionius said, ‘When our need was greater, we burdened no one, so how can we now receive gifts?’ (4) And so the guards were annoyed, for they usually had their cut of the gifts that arrived for the prisoners, and in their anger, they threw the group into the innermost part of the prison so that the prisoners would not receive all their gifts. (5) Having thus glorified God, they remained at peace when they offered the guards the usual gratuities; and the head of the prison changed his mind and transferred them back to the front part again. (6) They remained there saying, ‘Glory to the Lord, for what has happened to us is for the best.’ (7) For they had permission to engage in discussion and to pray day and night.

12. Nevertheless, many pagans (ethnē) came to them in the prison wanting to persuade them and marvelling at the answers they heard. (2) There also came those of the Christian brethren who had been dragged by force [to sacrifice]; they came with much wailing so that with each hour Pionius and his companions felt great sorrow, especially for the devout ones and those who had lived an upright life . . . [Pionius then embarks on his second speech, directed this time particularly towards lapsing Christians.]

15. When he had said these things and was urging them to leave the prison, the temple warden Polemon and the city cavalry commander (hipparchos) Theophilus arrived, together with the local security troops (diogmitai) and a large crowd, and they said: (2) ‘See now, Euctemon your leader has sacrificed, so you obey too. Lepidus and Euctemon are asking for you at the temple of the goddesses Nemeseis.’ (3) Pionius said, ‘Those who have been thrown into prison must await the proconsul. Why do you take on his role?’ (4) After saying many things, they went off, then returned again with the local troops and crowd, and the cavalry commander Theophilus said deceitfully, ‘The proconsul has sent word that you are to be taken to Ephesus.’ (5) Pionius said, ‘Let the man sent to take charge of us come here.’ The cavalry commander replied, ‘But it is a centurion, a person of considerable importance. If you refuse, I am a magistrate.’ (6) And seizing Pionius’ cloak he pulled it tight around his neck and passed it to one of the troops, almost strangling him in the process. (7) They arrived in the main square, together with Sabina and the others with them. They cried out loudly, ‘We are Christians!’ They threw themselves in the ground so as not to be taken to the place of the idols. Six of the local troops were carrying him head first, since they could not stop him from kicking them in the ribs with his knees and interfering with their hands and feet.

16. He shouted while those carrying him brought him and placed him on the ground near the altar, near which Euctemon remained in an attitude of worship. (2) And Lepidus said, ‘Why do you not sacrifice, Pionius?’ Pionius and those with him said, ‘Because we are Christians.’ (3) Lepidus said, ‘Which god do you worship?’ Pionius said, ‘The one who made the heavens, the earth, the sea, and all that is in them.’ (4) Lepidus said, ‘Is this the one who was crucified?’ Pionius said, ‘He whom God sent for the salvation of the world.’ (5) The magistrates let out great cries and laughed, and Lepidus cursed him. (6) But Pionius cried, ‘Respect piety, honour justice, acknowledge that which is of the same nature; obey your own laws. You punish us for disobedience, but you yourselves are disobedient; you have instructions to punish, not to treat with violence.’

17. A certain Rufinus who was present and had a reputation for being one of the better rhetors, said to him, ‘Stop, Pionius, don’t espouse these empty theories!’ (2) Pionius replied to him, ‘Are these your speeches? Are these your books? Socrates didn’t suffer these things from the Athenians. But now everyone is an Anytus and a Meletus. (3) Were Socrates, Aristides, Anaxarchus, and the rest espousing empty theories, according to you, because they practised philosophy, justice and steadfastness?’ (4) Hearing this, Rufinus was silent.

18. One of the people of eminent station and of grand repute in worldly terms, and Lepidus, said to him, ‘Do not cry out, Pionius.’ (2) He replied to him, ‘And you – do not use violence. Light the fire and we will climb onto it of our own accord.’ (3) A certain Terentius shouted from the crowd, ‘Are you saving one who is preventing others from sacrificing?’ (4) Finally they placed crowns on them, but they tore them to pieces and threw them away. (5) A public slave was standing by holding meat sacrificed to the idols. However, he did not dare to approach any of them, but ate it himself in front of everyone, he the public slave. (6) As they kept shouting, ‘We are Christians’, so that they could find nothing to do with them, they sent them back to the prison, and the crowd insulted them and beat them. (7) Someone said to Sabina, ‘Can’t you go and die in your home town?’ She said, ‘Where is my home town? I am the sister of Pionius.’ (8) Terentius, who at that time was staging the wild beast hunts in the amphitheatre, said to Asclepiades, ‘When you are condemned I will ask for you for my son’s gladiatorial shows.’ (9) Asclepiades replied to him, ‘You don’t scare me with that.’ (10) And so they were led back to the prison. As Pionius was entering the prison, one of the local troops struck him heavily on the head and wounded him, but Pionius said nothing. (11) But the hands of the one who had struck him, and also his sides, became swollen to the point where he could hardly breathe. (12) After they entered, they glorified God that they had remained unharmed in the name of Christ and that neither the enemy nor Euctemon the fraud had prevailed over them, and they did not stop encouraging themselves with psalms and prayers. (13) It was said that later Euctemon had demanded that he be compelled, and that he himself had taken a lamb to the temple of the two goddesses Nemeseis, and that after eating some of it, he had wanted to carry all of it, cooked, to his own house. (14) So he became an object of ridicule through his false oath, because he had sworn by the Fortune of the emperor and by the goddesses Nemeseis, crown on his head, that he was not a Christian, and, unlike the rest, he neglected nothing by way of denial.

19. Later, the proconsul came to Smyrna, and Pionius was brought before him and gave testimony, according to the official record that follows, on the 4th day before the Ides of March [12 March 250]. (2) When Pionius was brought before the tribunal, Quintillianus the proconsul began the enquiry. ‘What is your name?’ Reply: ‘Pionius.’ (3) The proconsul said, ‘Are you going to offer sacrifice?’ He replied, ‘No.’ (4) The proconsul asked, ‘To what cult or sect do you belong?’ He replied, ‘That of the catholics.’ (5) He asked him, ‘Of which catholics?’ He replied, ‘I am a presbyter of the catholic church.’ (6) The proconsul: ‘You are their teacher?’ He replied, ‘Yes, I teach them.’ (7) He asked, ‘You are a teacher of foolishness?’ Reply: ‘Of piety.’ (8) He asked, ‘What sort of piety?’ Reply: ‘Towards the God who created everything.’ (9) The proconsul said, ‘Sacrifice.’ He replied, ‘No, for I can pray only to God.’ (10) The other said, ‘We all worship the gods and the heavens and the gods who are in the heavens. Why are you giving your attention to the air? Sacrifice to it!’ (11) Reply: ‘I am not giving my attention to the air, but to him who made the air, the heavens, and all that is in them.’ (12) The proconsul said, ‘Tell me, who made them?’ He replied, ‘It is not possible to describe him.’ (13) The proconsul said, ‘Certainly it is God, that is to say Zeus, who is in the heavens; for he is the king of all the gods.’

20. Pionius remained silent and was strung up. He was asked, ‘Now then, are you going to offer sacrifice?’ He replied, ‘No.’ (2) Again he was asked when he was being tortured with the ‘talons’: ‘Change your mind; why have you lost your senses?’ He replied, ‘I have not lost my senses, but I fear the living God.’ (3) The proconsul: ‘Many men have offered sacrifice and they are alive and of sound mind.’ He replied, ‘I am not sacrificing.’ (4) The proconsul said, ‘Having been questioned, reflect a little within yourself and change your mind.’ He replied, ‘No.’ (5) He was asked, ‘Why do you seek death?’ He replied, ‘Not death, but life.’ (6) Quintillianus the proconsul said, ‘You’re not performing a great feat, striving after death, for those who find employment for small sums of money fighting against the wild beasts despise death; you too are just one of them. Ah well, since you are striving after death, you will be burned alive.’ (7) And from a wooden tablet was read in Latin, ‘Since he has confessed to being a Christian, we order Pionius to be burned alive.’

21. Pionius then came in haste to the arena, in the ardour of his faith, and when the secretary (commentariensis) arrived, he stripped himself. (2) After establishing that his body was unspoiled and of good bearing [i.e., despite his tortures], he was filled with a great joy. Raising his eyes to the heavens and thanking God that he had preserved him, he extended himself on the cross, and allowed the soldier to drive home the nails. (3) When he was nailed on, the executioner said to him once more, ‘Change your mind, and the nails will be removed.’ (4) But he replied, ‘I felt that they are there to stay.’ Then after reflecting a little, he said, ‘I am hurrying so as to awake more quickly’, meaning the resurrection of the dead. (5) Then they raised him on the cross, and afterwards also a presbyter named Metrodorus from the sect of the Marcionites. (6) It happened that Pionius was on the right and Metrodorus on the left, though both of them faced the east. (7) When they brought the wood and had piled it all around them in a circle, Pionius closed his eyes so that the crowd thought he had died. (8) But he was praying silently, and he opened his eyes when he had reached the end of his prayer. (9) And as the flames rose, his face was jubilant as he spoke the final amen and said, ‘Lord, receive my soul’, then, as if with a rattle, he died gently and without effort, and he entrusted his spirit to God, who has promised to watch over all blood and every soul unjustly condemned.

22. The blessed Pionius, having spent such a life, without fault, without reproach, without blemish, with his spirit always turned towards the all powerful God and towards the mediator between God and men, Jesus Christ our Lord, was judged worthy of such an end, and after having overcome in the great combat he entered by the straight gate into the vast and great light. (2) The crown was also manifested physically. For after the fire had gone out, we approached him and saw the body of an athlete in its strength and dignity. (3) Indeed his ears had not been deformed, his hair remained firmly on the scalp of his head, and his chin was adorned as if with the first flush of a youthful beard. (4) Moreover his face was radiant with a marvellous grace, so that the Christians were strengthened again in their faith, but the unbelievers returned home fearful, with deeply disturbed consciences.

23. These events took place under the proconsul of Asia, Julius Proclus Quintillianus, when the consuls were the emperors Gaius Messius Quintus Trajanus Decius Augustus, for the second time, and Vettius Gratus, on the 4th day before the Ides of March according to the Romans [12 March 250], and according to the calendar of the province of Asia, on the 19th day of the sixth month, on the day of the sabbath, at the tenth hour, and according to our reckoning under the kingship of our Lord Jesus Christ, to whom be glory for ever and ever. Amen.

2.13 Persecution by the emperor Valerian: Cyprian Letter 80

This letter from the bishop of Carthage to a fellow north African bishop is justly famous for providing valuable insights into the persecution of the church by the emperor Valerian. His first move, in 257, was to exile clergy who refused to sacrifice and to forbid Christians to meet or enter cemeteries. This letter, from mid-258, shows how the emperor reacted as it became clear that these sanctions were proving insufficient, namely the introduction of much more severe penalties for the church’s leadership and its most socially prominent supporters. It is also important for what it implies about the extent to which Christianity had by this stage penetrated into the upper echelons of Roman society, while the fact that Cyprian was able to obtain forewarning of Valerian’s measures confirms the presence of Christians in high places at Rome. Like Xistus, the bishop of Rome referred to in the letter, Cyprian himself was soon to suffer martyrdom (for a contemporary account of which, see Musurillo 1972: 168–75). This persecution continued until 260, when Valerian’s capture by the Persians led his son and co-emperor Gallienus to call a halt, thereby initiating a period of peace for the church which lasted until the commencement of the Diocletianic persecution in 303.

Further reading: Clarke 1984–9: vol. 4, 8–14, 296–310.

Cyprian to his brother Successus

1. (1) The reason I did not write to you immediately, dearest brother, is because all the clergy have been under the threat of the contest [of persecution] and have been unable to leave here at all. Consistent with the dedication of their souls, all are ready for the divine and heavenly crown [of martyrdom]. But you should know that those whom I sent to the city [of Rome] for this reason – namely that they should find out and convey to us the truth about whatever has been decreed concerning us – have returned. For many different unconfirmed reports have been current. (2) But the real situation is actually as follows: Valerian has sent a rescript to the senate to the effect that bishops, presbyters and deacons are to be punished immediately, but that senators, leading officals and Roman equestrians should be deprived of their rank and stripped of their property and if after the confiscation of their assets they persist in being Christians, they also are to undergo capital punishment; women of this status are to lose their property and be sent into exile, and any members of the imperial household who have either previously confessed or do so now are to have their property confiscated and be sent in chains to the imperial estates. (3) The emperor Valerian also appended to his decree a copy of the letter which he has produced for provincial governors concerning us. We are daily expecting this letter to arrive, standing firm in the faith, ready to undergo suffering, awaiting the crown of eternal life from the bounty and favour of the Lord. (4) Moreover you should know that Xistus was executed in the cemetery on the 8th day before the Ides of August [6 August], together with four deacons. But the authorities in the city [of Rome] daily press on with this persecution, so that anyone brought before them is punished and their possessions are claimed by the imperial treasury.

2. I ask you to make these facts known to our other colleagues also, so that our brethren everywhere can be strengthened by their encouragement and be prepared for the spiritual struggle, so that every one of our people reflects on immortality rather than on death and, devoted to the Lord with complete trust and absolute courage, they may rejoice rather than be afraid in this confession, in which they know the soldiers of God and of Christ are not killed but crowned. I pray for your well-being in the Lord always, dearest brother.