Figure 7.7 The temple of Isis at Philae

CHRISTIANISATION AND ITS LIMITS IN THE FIFTH AND SIXTH CENTURIES

The central theme in any consideration of pagans and Christians during the fifth and sixth centuries must be the process of Christianisation and its limits, even if the concept is fraught with difficulties (cf. Hunt 1993b: 143; Dijkstra 2008: 14–23). It is an enormous subject, and this chapter can do no more than try to highlight some of the key issues and themes. Unlike the preceding four chapters which by and large adhere to a clear chronological framework, this one is organised on a thematic basis.

The first four items illustrate the fundamental point that pagan practices continued well after imperial legislation had banned them, whether in urban (7.1, 7.2, 7.3) or rural contexts (7.4).

The next group of extracts focuses on the question of temples and their fate. The first involves a closed temple apparently turned into a church, but eventually demolished when it became clear that it remained a focus for ongoing pagan sympathies (7.5). This is followed by the case of a temple which was allowed to continue to function through the fifth century, probably for political reasons (7.6), until eventually converted into a church in the sixth century (7.7). The final extract presents a further famous example, from the post-Roman west, of the triumph of pragmatism in dealing with pagan shrines (7.8).

As noted previously (5.1b), pagan religious ceremonies were often closely linked with various traditional forms of public entertainment, and the next extract illustrates the problems the church authorities had in dissuading their congregations from participation, including valuable detail on how layfolk tried to justify their involvement (7.9).

An item in the opening chapter (1.10) directed attention to worries about the future as a common reason for individuals to seek divine assistance, and of course that motivation did not disappear in subsequent centuries. What is of interest, if unsurprising, is the way some of the methods employed in Christian contexts owed clear debts to pagan traditions (7.10, 7.11).

This section of the volume began with a calendar, so there is a certain symmetry in including part of one from the mid-fifth century that presents an intriguing blend of pagan and Christian festivals (7.12).

As to why Christianisation often made slow and variable progress, a number of general considerations can be suggested in addition to those implicit in some of the specific situations represented in this chapter. As far as imperial legislation was concerned, the fact that an emperor issued pronouncements prescribing punishments for sacrifice or the closing of temples did not necessarily mean such measures were implemented uniformly throughout the empire. That depended to a significant extent upon the willingness of officials in the different provinces to do so, and that was not always the case, whether because particular officials were not themselves Christians or because of administrative inertia (cf. Bradbury 1994: 132–9). There is the further point that some long-standing social practices were so intertwined with Roman religious traditions that it was very difficult to eliminate the latter without jeopardising the former, most obviously in the area of public entertainment.

Moreover, broader historical circumstances during the fifth and sixth centuries also played a part. In the west, the imperial political infrastructure gradually gave way to various independent kingdoms ruled by Germanic peoples, most of whom had been converted to Arian Christianity. This often diverted the attention of orthodox clergy living in these kingdoms towards doctrinal issues, especially in north Africa where the Vandals pursued discriminatory policies against non-Arians. In the east, meanwhile, a new doctrinal controversy emerged to absorb much of the energies of church leaders, namely the fierce arguments over the relationship of the human and the divine within Christ associated initially with Nestorius and Cyril of Alexandria (7.13). The Council of Chalcedon in 451 tried to resolve this issue (7.14), but was no more successful than Nicaea had been in 325, instead fuelling the growth of the so-called Monophysite movement, which was especially strong in Egypt and remained an ongoing preoccupation through the sixth century. Such distractions must also have contributed indirectly to the longevity of pagan practices in many parts of the empire.

Further reading: Gregory 1986; Bowersock 1990; Chuvin 1990; Whitby 1991; Trombley 1993; Klingshirn 1994: ch. 8; Brown 1995, 1998b; Fletcher 1997: chs 1–4; MacMullen 1997; Trout 1999: 173–86; Kristensen 2013; Leone 2013; sourcebook: Hillgarth 1986.

7.1 Pagan activities in late fifth-century Caria: Zacharias Life of Severus pp. 39–41

The Life of Severus (originally written in Greek, but surviving only in a Syriac translation) is a biography (down to 512) of the eminent Monophysite theologian and bishop Severus of Antioch (465–538), whose author, a lawyer and later himself a bishop, knew Severus from their student days in Alexandria in the 480s. The focus of this extract, however, is a fellow student of theirs named Paralius who came from a prominent pagan family in the Carian city of Aphrodisias in Asia Minor, but converted to Christianity while in Alexandria. It provides insight into pagan activities in Aphrodisias during the 480s (including the ongoing importance of oracles), particularly at the time of a major rebellion against the emperor Zeno in 484 which, on the evidence here, had a religious as well as a political dimension. Illus and Leontius were Isaurians who had previously been close associates of Zeno, while Pamprepius was an eminent pagan scholar (on whom see Bowersock 1990: 61–2). Paralius and his brothers, Demochares and Proclus, are not otherwise known, though their prominence within Aphrodisian society is evident, but the Asclepiodotus mentioned towards the end of the extract has been identified with a leading citizen of the city mentioned in two inscriptions from this period (Roueché 1989: 85–93). For further discussion, see Trombley 1993: vol. 2, 20–9; for an English translation of the whole Life of Severus, see Brock and Fitzgerald 2013.

He [Paralius] now became concerned about his two other brothers who were pagans in Aphrodisias. One of them was a legal advocate in the district, and was called Demochares; the other was called Proclus and was a professor in the city. He wrote a letter of warning to them, in which he told them all that had happened. He encouraged them immediately to look to the road of repentance and willingly to choose the worship of the one God, I mean the Trinity, holy and one in essence. He urged that they would learn (p. 40) by actions what sort of power Christianity had. He reminded them of stories such as that of the rebellion of Illus and Pamprepius, telling them, ‘Remember how many sacrifices we offered, when we were pagans in Caria, to the gods of the pagans, when we put questions to those supposed gods, and we cut open livers and inspected them by magic, to learn if we – Leontius, Illus, Pamprepius and those who rebelled with them – would overcome the emperor Zeno, of pious end. We received a myriad of oracles at the same time with signs that the emperor Zeno would not be able to meet their attack, but that the time had come when Christianity would be destroyed and pass away, and when pagan worship was going to recover. However, the outcome of their consultation of these oracles showed they were false, like those given by Apollo to Croesus the Lydian and to Pyrrhus the Epirote. You know also what happened when subsequently we sacrificed in those places outside the city: not a single sign or apparition or response was given, even though we had been accustomed previously to become aware of some such illusion. (p. 41) We were at a loss as we enquired and pondered much about what this meant. We changed the places of sacrifice. In spite of that, the supposed gods remained mute and everything to do with them remained ineffective. We thought they were angry with us and finally had the idea that perhaps one of our group had a will opposed to what we wanted to achieve. We asked each other whether we were all of the same sentiment, and discovered a young man who had made the sign of the cross in the name of Christ and that our concern was thereby rendered vain and our sacrifices ineffective, since the supposed gods often flee at the name of Christ and the sign of the cross. We were at a loss to explain this, and Asclepiodotus, the others sacrificing and the magicians inquired into the matter. One of them thought he had a solution to the problem and said, “The cross is a sign indicating that a man has died by violence, so it is understandable that the gods loathe shapes of this sort.”’

7.2 Persecution of pagans in sixth-century Antioch: Life of the Younger St Symeon the Stylite 161, 164

The younger Symeon was a holy man who lived on one of the mountains near Antioch (521–92), and the modern editor of his biography considers it to have been written by one of Symeon’s disciples. Although this episode, probably from 555, is couched in high-flown language, the official at the centre of the investigations, Amantius, is known from an independent source which describes his involvement in the suppression of a Samaritan revolt ( John Malalas Chronicle p. 487), and suppression of paganism is certainly a general feature of the emperor Justinian’s religious policies, as is book-burning (Maas 1992: ch. 5).

Further reading: Trombley 1994: 182–95; Millar 2014.

(161) Within a four-month period of the holy man predicting all these events, that official arrived. His name was Amantius, and before coming to the city of Antioch, he destroyed many of the unrighteous found en route, so that men shuddered with fear at his countenance. For everywhere he suppressed all evil-doing whether in word or deed, inflicting punishment, including death, on those who had gone astray, so that from then on even those living a blameless life feared his presence. For he removed, as much as was possible throughout the east, all quarrelling, all injustice, all violence, and all wrongdoing. When this had happened, God showed his servant another vision, which he reported to us: ‘A decision has come from God against the pagans (Hellēnes) and heretics (heterodoxoi), that this official will reveal the idolatrous errors of the atheists and gather together all their books and burn them.’ When he had foreseen these things and reported them, zeal for God took a hold of that official and after investigating, he found that the majority of the leaders of the city and many of its inhabitants were preoccupied with paganism (hellēnismos), Manichaeism, astrological practices, automatism, and other hateful heresies. He arrested them and put them in prison, and after gathering together all of their books – a huge number – he burned them in the middle of the stadium. He brought out their idols with their polluted accoutrements and hung them along the streets of the city, and their wealth was expended on numerous fines. . . . (164) . . . Then the judge took his seat on the tribunal and subjected to special punishments some of them, who had confessed to having committed many terrible crimes on account of their ungodliness; some he ordered to do service in the hospices, while others, who called themselves clerics, he sent to receive instruction in monasteries; still others he sent off into exile, while some he condemned to death. But by imperial command, the majority of them, who pleaded ignorance as an excuse and promised to repent, he released without further investigation. And so it came about that after being corrected, everyone was dispersed and none of them remained in prison, with the exception of one who had caused many disturbances during times of public unrest, on account of which he deserved punishment. So it was an appropriate time to recall the judgements of God and to sing the praises of his inexpressible benevolence towards us.

7.3 Persecution of pagans in sixth-century Sardis: I. Sardis 19

This damaged inscription corroborates evidence in other sources (e.g., 7.2) of stringent action undertaken by Justinian against those identified as pagans in the mid-sixth century. The second title of the investigating officer is a post established in 539 ( Justinian Novels 82, on which see further Roueché 1989: 147–8), so this enquiry must have taken place after that date. The phrase used to describe pagans also features in an imperial law of the late fifth/sixth century ( Justinianic Code 1.11.10), and it is a reasonable assumption that Hyperechius’ activities were designed to enforce this legislation. It also appears that the partially preserved name of the individual punished by Hyperechius was the first in a list on further blocks of stone that have not survived. The punishment imposed is of interest in the light of the language of disease that features so strongly in religious polemic during Late Antiquity (though those sent to hospices in 7.2 (164) go not to recuperate, but to serve).

Further reading: Trombley 1994: 180–81.

+ List of the decisions reached and of the unholy and loathsome pagans (Hellēnes) banished by Hyperechius, the highly esteemed judicial officer (referendarius) and imperial judge (theios dikastos). < . . . >ipos was <banished> to the hospice for the sick (ton tōn arostōn xenona) for ten years < . . . >

7.4 Christianisation in rural Egypt: Besa Life of Shenoute 83–84

During his long life (c. 355–466?), Shenoute, abbot of the White Monastery at Atripe in southern Egypt, gained a well-deserved reputation as a forceful opponent of paganism and heresy. This extract, from the Coptic biography written by his successor, Besa, illustrates the persistence of pagan practices in rural areas of a region of the empire long exposed to Christianity, and Shenoute’s blunt strategy in response (cf. 6.10). On this specific episode, see Trombley 1993: vol. 2, 207–19; Frankfurter 1998a: 68–9; for Shenoute more generally, see Lopez 2013.

(83) Another time, our holy father apa Shenoute arose to go to the village of Pleuit in order to throw down the idols which were there. So when the pagans came to know of this, they went and dug in the place which led to the village and buried some [magical] potions [which they had made] according to their books because they wanted to hinder him on the road. (84) Our father apa Shenoute mounted his donkey, but when he began to ride down the road, as soon as the donkey came to a place where the potions had been buried, it would stand still and dig with its hoof. Straightaway the potions would be exposed and my father would say to the servant: ‘Pick them up so that you can hang them round their necks.’ Time and time again the servant who was going with him would beat the donkey, saying: ‘Move!’ But my father would say to him: ‘Let him be, for he knows what he is doing!’, and again he would say to the servant: ‘Take the vessels and keep them in your hand until we enter the village so that we can hang them round their necks.’ When he entered the village, the pagans saw him with the magical vessels which the servant had in his hands. They immediately fled away and disappeared, and my father entered the temple and destroyed the idols, smashing them one on top of the other.

(tr. D. Bell)

7.5 The fate of a temple in Carthage: Quodvultdeus The Book of the Promises and Prophecies of God 3.38 (44)

Quodvultdeus, bishop of Carthage from c. 437 to the early 450s, here recounts how the Christian authorities dealt with a temple in Carthage dedicated to the goddess Caelestis – the Romanised version of the important Punic deity Tanit (Halsberghe 1984). Initially, the temple was closed, presumably as part of the more general shutting of pagan sanctuaries in north Africa in 399 known from other sources. Then, probably in 407/8, the Christian community gathered there for some sort of ceremony. Quodvultdeus’ account seems to indicate that this marked the conversion of the temple to a church, but the eventual demolition of the building c. 421 gives pause for thought. At any rate, it is this denouement which is particularly significant, since it was apparently inspired by worries about the temple building remaining a focus for pagan hopes and implies that pre-Christian religious traditions still commanded wide support (cf. Augustine Letters 91.8).

A few points of detail warrant comment. The author’s wordplay on the name Caelestis – which means ‘heavenly’ in Latin – is not easy to preserve in translation, while the point of the inscription is that the temple must originally have been dedicated during the reign of Marcus Aurelius (161–80), who, like all pagan emperors (and indeed some fourth-century Christian ones), held the office of chief priest (pontifex maximus). Finally, although the reference to the temple land becoming a place for burial of the dead is usually taken to mean a cemetery, the ‘dead’ here could be the dispossessed pagan deities themselves.

Further reading: Braun 1964: 70–74, 574–8; Lepelley 1979–81: vol. 1, 42–4; vol. 2, 354–7; Hanson 1978; Leone 2013: ch. 2.

In Africa, at Carthage, Caelestis – as they called her – had a temple of very substantial size ringed around by sanctuaries of all their gods. Its precinct was decorated with mosaic pavements and expensive columns and walls, and extended nearly 1,000 paces. When it had been closed for a long time and, from neglect, thorny thickets invaded the enclosure, and the Christian inhabitants wanted to claim it for the use of the true religion, the pagan inhabitants (gentilis populus) clamoured that there were snakes and serpents there to protect the temple. This only aroused the fervour of the Christians all the more and they removed everything with ease and without suffering any harm so as to consecrate the temple to the true celestial king and master. And in fact when the solemn feast of holy Easter was celebrated and a great crowd had gathered there and was approaching from every direction full of curiosity, the father of many priests and a man worthy of remembrance, the bishop Aurelius – now a citizen of the heavenly homeland – placed his chair there on the spot [previously occupied by the cult statue] of Caelestis and sat down. I myself was there at the time with companions and friends, and while, in our youthful impatience, we were turning in every direction and inquisitively studied each detail according to its importance, something amazing and unbelievable confronted our gaze: on the façade of the temple, in very large letters of bronze, an inscription was written – ‘Aurelius the chief priest ( pontifex) dedicated [this]’. When they read this, the people marvelled at this deed inspired by the prophetic Spirit in a former time, which the prescient ordering of God had brought to this appointed outcome. And when a pagan made known a false prophecy, as if from the same Caelestis, to the effect that the sacred way and the temples would once again be restored to the ancient ritual of their ceremonies, God, the true God, whose prophetic utterances do not know how to lie or deceive at all, brought it about, under Constantius [III] and the empress [Galla] Placidia – whose son, the devout and Christian Valentinian [III], is now emperor – and by the efforts of the tribune Ursus, that all those temples were razed to the ground, leaving, appropriately, a piece of land for the burial of the dead; and the hand of the Vandals [who occupied Carthage in 439] has now destroyed that sacred way without leaving any reminder of it.

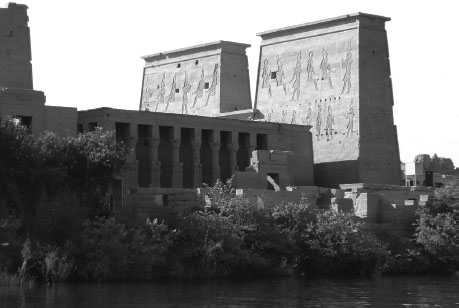

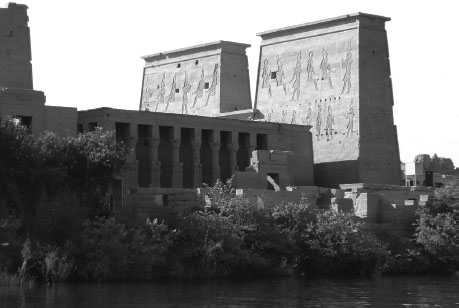

7.6 The temple of Isis at Philae in the mid-fifth century: IGPhilae 197 and Priscus History fr. 27.1

By the mid-fifth century, many temples had either been destroyed or converted into churches, and open celebration of pagan rites at cult centres was the exception. One location where such rites continued to be practised, however, was the temple of Isis at Philae, on the Nile in southern Egypt (cf. 1.8), illustrated here by an inscription placed by one of the priests at the entrance to the shrine of Osiris on the roof of the temple of Isis (celebrations in honour of Osiris were held during the month of Choiak, when this inscription was carved [Bernand 1969: 246]). Relative geographical isolation no doubt played a part in Philae’s apparent immunity from enforced changes in other parts of the empire, but it would appear from the second extract, by the important fifth-century historian Priscus, that political considerations were also a major factor – in this case, maintaining good relations with the Blemmyes and Nobades, the peoples who replaced the kingdom of Meroe as the empire’s neighbours to the south of Egypt. This situation did not, however, last very much longer, for the last inscriptions with pagan content date to 456/7, and their termination has been interpreted as signalling the end of formal pagan worship at Philae, as the region became increasingly Christianised. For detailed discussion of the inscription, see Bernand 1969: 237–46. On the religious evolution of Philae during Late Antiquity, see Dijkstra 2008.

(a) IGPhilae 197

The act of worship of Smetchem, the chief priest ( protostolistes), whose father is Pachoumios, prophet (5) and whose mother is Tsensmet. I became chief priest in [the year] 165 [of the era] of Diocletian [448/9]. I came here (10) and carried out my function at the same time as my brother Smeto, successor of the prophet (15) Smet, son of Pachoumios, prophet. We give thanks to our mistress Isis and to our lord Osiris (20) for a blessing today, 23[rd day of the month] Choiak, [the year] 169 [of the era] of Diocletian [20 December 452].

(b) Priscus History fr. 27.1

When the Blemmyes and Nobades were defeated by the Romans, both peoples sent envoys to Maximinus on the subject of peace, wishing to conclude a treaty, and they said they would observe it while Maximinus remained in the region of Thebes. But when he would not agree to a treaty for this period of time, they said they would not bear arms during his lifetime. But when he would not accept this second proposal of their embassy, they agreed to a hundred-year treaty. By its terms, Roman prisoners were to be released without ransom, whether captured in that incursion or another; cattle which had been carried off were to be returned, and compensation paid for those which had been consumed; and hostages of good birth were to be handed over by them as a guarantee of the treaty. For their part, they were to have unhindered access to the temple of Isis in accordance with traditional custom, while the Egyptians were to be responsible for the river boat in which the statue of the goddess was placed and transported. For at a specified time the barbarians bear the wooden image to their own country to consult it for oracles, before restoring it to the island. Maximinus considered the temple at Philae a suitable location in which to formalise the treaty, and certain men were sent there. When the representatives of the Blemmyes and the Nobades who had negotiated the treaty reached the island, the agreement was committed to writing and the hostages were handed over. . . .

7.7 The end of the cult of Isis at Philae: Procopius Wars 1.19.31–5 and IGPhilae 203, 201

Figure 7.7 The temple of Isis at Philae

Source: Rémih/Wikimedia Commons

The first passage is the account by the important sixth-century historian Procopius of Justinian’s termination of the cult of Isis at Philae, on the Nile in southern Egypt, which has been dated to the mid-530s. It is, however, an account which must be treated with care. Although Justinian was well-known for his willingness to enforce conformity with his Christian convictions, it is clear that, despite Procopius’ statement about its destruction, the temple remained standing (to the present day: Figure 7.7) and was transformed into a church dedicated to Stephen, the very first martyr. Furthermore, if as noted above (7.6), pagan cult at Philae actually ended in the late 450s, then Procopius’ report says more about imperial propaganda in Constantinople than it does about imperial policy in Philae. The temple’s transformation into a church has usually been assumed to have followed Narses’ seizure of the cult statues, but may not actually have happened until the 560s. The first inscription, on the wall of the main entrance to the temple of Isis, is one of a number recording the role of the local bishop Theodore (in post from c.525 to at least 577) in this process; the image of Stephen with which this inscription was associated was visible in the early nineteenth century, but has since been destroyed by the action of the Nile waters (Bernand 1969: 264–5). The second inscription, beside the entrance to the sanctuary of the temple of Isis, has been seen as having an apotropaic function vis-à-vis the demons believed to inhabit pagan shrines. For detailed discussion see Dijkstra 2008.

(34) When this emperor [Diocletian] found there was an island in the River Nile very close to the town of Elephantine, he built a very strong fortress on it, and established there some shared temples and altars for the Romans and these barbarians, and placed priests from each people in the fortress, confident that their sharing in things sacred to them would result in friendliness ( philia) between them. (35) For this reason he named the place Philae. Both these peoples, the Blemmyes and the Nobades, reverence all the other gods which the pagans (Hellēnes) acknowledge, as well as Isis and Osiris, not to mention Priapus. (36) The Blemmyes are also in the habit of sacrificing humans to the sun. These barbarians have used these temples on Philae until my own day, but the emperor Justinian decided to demolish them. (37) So the commander of the troops there, Narses – a Persarmenian by origin, whose desertion to the Romans I have previously mentioned – pulled down the temples at the emperor’s command. He placed the priests in prison and sent the cult statues to Constantinople.

(b) IGPhilae 203

+ The very faithful friend of God, Father Theodore, bishop, who through the generosity of our Lord Christ has transformed this temple into a church of the holy Stephen, (5) [dedicated this image]. A blessing on him through the power of Christ. + [This inscription was put up] by Posios, deacon and warden. +

(c) IGPhilae 201

The cross + has conquered – it always conquers. +++

7.8 Gregory the Great’s strategy in Britain: Bede Church History of the English People 1.30

Although Christianity had had a presence in Roman Britain (Thomas 1981), the arrival of pagan Anglo-Saxon settlers from the Continent during the fifth century meant that much of the island had to be re-evangelised, a task which Pope Gregory the Great (590–604) organised at the end of the sixth century. Bede (c. 672/3–735), a monk at Jarrow in northern England, preserved the famous letter Gregory wrote in July 601 to his missionaries there with instructions on how they should deal with pagan shrines.

Further reading: Markus 1970; Wallace-Hadrill 1988: 44–5; Mayr-Harting 1991: ch. 3; Fletcher 1997: 111–19; Demacopoulos 2008.

To my most beloved son, Abbot Mellitus, Gregory, servant of the servants of God. Since the departure of our companions and yourself I have felt much anxiety because we have not happened to hear how your journey has prospered. However, when Almighty God has brought you to our most reverend brother Bishop Augustine, tell him what I have decided after long deliberation about the English people, namely that the idol temples of that race should by no means be destroyed, but only the idols in them. Take holy water and sprinkle it in the shrines, build altars and place relics in them. For if the shrines are well built, it is essential that they should be changed from the worship of devils to the service of the true God. When this people see their shrines are not destroyed they will be able to banish error from their hearts and be more ready to come to the places they are familiar with, but now recognizing and worshipping the true God. And because they are in the habit of slaughtering much cattle as sacrifices to devils, some solemnity ought to be given them in exchange for this. So on the day of the dedication of the festivals of the holy martyrs, whose relics are deposited there, let them make themselves huts from the branches of trees around the churches which have been converted out of shrines, and let them celebrate the solemnity with religious feasts. Do not let them sacrifice animals to the devil, but let them slaughter animals for their own food to the praise of God, and let them give thanks to the Giver of all things for His bountiful provision. Thus while some outward rejoicings are preserved, they will be able more easily to share in inward rejoicings. It is doubtless impossible to cut out everything at once from their stubborn minds: just as the man who is attempting to climb to the highest place, rises by steps and degrees and not by leaps . . .

(tr. B. Colgrave)

7.9 The problem of public shows: Jacob of Serugh Homily 5

Public entertainment in the Roman world was closely bound up with religion, whether it be that the games in question honoured a particular deity, or the plays included re-enactments of stories from mythology involving gods and goddesses. These features raised grave doubts in the minds of church leaders about the propriety of Christians attending such occasions, yet it is clear that many continued to find them irresistible (cf., e.g., Augustine Sermon 51). The sermon from which the following extracts derive is one of many in which clergy tried to dissuade their congregations from participation. Written in Syriac, its author was a prominent Syrian churchman of the late fifth and early sixth century (451–521) who ended his life as bishop of Batnae (Serugh). It is of particular interest because he discusses the arguments of those he is trying to dissuade.

Further reading: Markus 1990: ch. 8.

[The defence of those who frequent the spectacles] ‘It is a show’, they say, ‘not paganism. What will you lose if I laugh? And since I deny the gods, I shall not lose through the stories concerning them. The dancing of that place [the theatre] gladdens me, and, while I confess God, I also take pleasure in the play, while I do not thereby bring truth to nought. I am a baptised [Christian] even as you, and I confess one Lord; and I know that the mimings which belong to the spectacles are false. I do not go that I may believe, but I go that I may laugh. And what do I lose on account of this, since I laugh and do not believe? [As for] those things in the stories which are mimed concerning the tales of the idols, I know that they are false; and I see them – laughing. What shall I lose on account of this? I am of the opinion that I [shall lose] nothing. Why then do you blame him who is without blame?’ . . .

[Jacob’s reply] ‘Who can bathe in mud without being soiled? . . . You are the assembly of the baptised, whose husband and God is Jesus; and how will he not become jealous, since you praise idols? . . . These worthless spectacles which are mimed with dancing, I will tell [you] without shame from what source they come. When the physician lances a boil, he bespatters his hands with festering matter, and he makes his fingers swim in foul blood on account of the healing [of the patient]. He soaks his clean hands in loathsome pus, and he does not shrink, and he defies the foul smell that he may scrape away the matter of the boil. In accordance with this rule I approach the boil which the spectacles have caused, in order that, when the tongue lances it, and is bespattered with it, it may become clean. I will say concerning their plays how futile their stories are, lest any man suppose that rashly I bring shame upon their deeds.

‘They say that the grandfather of their gods [Kronos] was devouring his sons, and as a dragon [swallows] a serpent, so he was swallowing the child of his belly. This is the beginning of the story of the dancing of the Greeks; this one thing alone is sufficient that you should despise all their tales. . . . But his son [Zeus] who was saved from him [Kronos] became famous through adultery, and, under various forms, he committed fornication with many women . . . ’

7.10 Christian methods of divination: Council of Vannes Canon 16

The decisions of this Gallic council held some time between 461 and 491 included the condemnation of a form of divination known as the ‘lots of the saints’ (sortes sanctorum), which ‘involved the random selection of oracular responses from a collection designed for the purpose’ (Klingshirn 1994: 220). An analogous practice was the sortes Biblicae, in which books of the Bible were opened at random (ideally on the altar of a church) for guidance about the future. In this instance, it is noteworthy that clergy are singled out for resorting to the practice. The Council of Agde (506) repeated this canon virtually word for word, with the inclusion of the laity (Canon 42).

Further reading: Metzger 1988; Klingshirn 1994: 219–21; Gamble 1995: 237–41; MacMullen 1997: 139, 237–8.

Lest something which very seriously infests the faith of the catholic religion should perhaps appear to have been overlooked, namely that quite a number of clergy concern themselves with augury and under the name of a false religion called the ‘lots of the saints’ (sortes sanctorum), they practise the art of divination and predict the future by the study of writings of any sort – any clergy found either carrying out or teaching this shall be treated as outside the church.

7.11 A Christian oracle: P. Rendel Harris 54 and P. Oxy. 1926

These two short papyri from sixth-century Egypt form a pair of requests for help in making a business decision. They were written by the same person on a single sheet of papyrus which was then cut in half; although there are some variations in phraseology, the only essential difference is that the first looks for an answer in the affirmative, the second in the negative (Youtie 1975). The individual seeking help directs their request to the Christian God and a Christian saint, yet the technique employed owes a clear debt to traditional Egyptian methods of consulting oracles, whereby the divine answer was obtained by lot (cf. Browne 1976: 56–8 for comparisons with 1.10). Although the survival of a matching pair like this is rare, many individual requests have been recovered, ‘suggest[ing] that oracles were no “behind-the-scenes” favour but rather a common service to the community that was offered by certain churches and monasteries’ (Frankfurter 1998a: 194). On the reverse of both papyri are the Greek letters χμγ (chi-mu-gamma), written three times and interspersed with crosses, but their significance remains a matter for debate. Some scholars have seen them as an acrostic for ‘Mary bore Christ’ or the like, while others have proposed that they are an isopsephism – that is, they possess some sort of numerological significance, arising from the fact that the letters of the Greek alphabet could be used to represent numbers (in this case 643). Whatever the answer, the formula certainly occurs in contexts implying its use as a sort of protective amulet (see Llewellyn 1997 for further discussion).

+ My Lord God Almighty and St Philoxenus my patron, I beg you by the mighty name of the Lord God, if it is your will and you are helping me to acquire the money-changing business, I beg that you bid me to know and to make an offer. +

(b) P. Oxy. 1926

+ My Lord God Almighty, and St Philoxenos my patron, I beg you by the mighty name of the Lord God, if it is not your will that I make an offer for the money-changing business and for the weighing office, bid me to know not to make an offer. +

7.12 A Roman calendar from the mid-fifth century: an extract from the Calendar of Polemius Silvius

The text below comprises the entries for one month from a calendar compiled in 448/9 by a Christian writer in Gaul, Polemius Silvius, and dedicated to Eucherius, bishop of Lyons. Its chief interest lies in its accommodation of many traditional Roman observances and festivities – some with distinctly religious significance –alongside Christian festivals. Most matters of detail are glossed below, but note, first, that ‘games’ (ludi) focused on various types of theatrical performance while ‘circus games’ (circenses) meant chariot-races, and second, that the Romans counted inclusively, so that, e.g., ‘the second day before . . . ’ is actually the day before. The periodic references to the weather are generally thought to reflect the influence of Columella’s first-century treatise on agriculture.

Further reading: Salzman 1990: 242–6; Degrassi, in Polemius Silvius, Calendar 1963: 388–405 (for commentary on points of detail, though in Latin).

JANUARY

Named after Janus. It has 31 days. It is called Sebet by the Jews, Tybi by the Egyptians, Posideon by the Athenians, Edineus by other Greeks [i.e., the Macedonian month of Audinaios].

The Kalends [1 January]

Named from the Greek kalein, that is from ‘calling’, because at that time the people were called to an assembly at the rostrum in Rome

4th day before the Nones [2 January]

Privately funded circus games. Southerly wind, sometimes with rain

3rd day before the Nones [3 January]

Day suitable for divination. Birthday of Cicero. Games

2nd day before the Nones [4 January]

Compitalian Games [to appease guardian spirits of cross-roads]

The Nones [5 January]

So named because the ninth day (nonus dies) separates them from the Ides. Portends a storm

8th day before the Ides [6 January]

Epiphany, on which day in times past the star which announced the birth of the Lord was seen by the Magi. Wine was made from water and the Saviour was baptised in the River Jordan. Southerly wind sometimes, or westerly wind

7th day before the Ides [7 January]

First ‘napkin’ (mappa) of the consul [to start chariot-races in celebration of gaining the consulship], which is so called for this reason, because when King Tarquin of Rome was taking lunch in the Circus on a day when circus games were held, he threw his own napkin from the table outside in order to give the signal for the charioteers to race after lunch

6th day before the Ides [8 January]

Southerly wind sometimes and hail

5th day before the Ides [9 January]

Prescribed meeting of the senate. Substitute consuls are designated and praetors

4th day before the Ides [10 January]

3rd day before the Ides [11 January]

[Festival of] the Carmentalia from the name of the mother of Evander [viz. Carmentis, who, in one tradition about Rome’s origins, advised her son to settle at the subsequent site of Rome]

2nd day before the Ides [12 January]

Birthday of our Lord Theodosius [II] Augustus [408–50] on the previous day

The Ides [13 January]

Named from the Greek eidein, from ‘seeing’, because, before this present [type of] year was valid [viz. the solar year, which superseded the lunar cycle], in the middle of the month, the moon, which began on the Kalends and from which we learned that the months (menses) were named [from the Greek for moon, mene?], was seen to be full. Second ‘napkin’ [for chariot-races in honour of Jupiter the Protector]. Sometimes wind or a storm

19th day before the Kalends of February [14 January]

18th day before the Kalends [15 January]

Anniversary of [the accession of the emperor] Honorius [395–423]. Circus games. Sometimes a southerly wind and rain

17th day before the Kalends [16 January]

16th day before the Kalends [17 January]

Palatine Games [for three days, in memory of the emperor Augustus]

15th day before the Kalends [18 January]

Games

14th day before the Kalends [19 January]

Games

13th day before the Kalends [20 January]

Birthday of [the emperor] Gordian [238–44]. Circus games

12th day before the Kalends [21 January]

Games. South-westerly wind. Portends a storm

11th day before the Kalends [22 January]

Anniversary of the holy martyr Vincentius. Rainy day

10th day before the Kalends [23 January]

Prescribed meeting of the senate. Quaestors are designated in Rome

9th day before the Kalends [24 January]

Birthday of [the emperor] Hadrian [117–38] [cf. 1.1]. Circus games

8th day before the Kalends [25 January]

Sometimes a storm

7th day before the Kalends [26 January]

6th day before the Kalends [27 January]

Games of the Twin Gods in Ostia, which was the first colony established

5th day before the Kalends [28 January]

Games. Southerly or south-westerly wind. Sometimes a wet day

4th day before the Kalends [29 January]

Games

3rd day before the Kalends [30 January]

Portends a storm

2nd day before the Kalends [31 January]

Circus games for the victory [of Constantius II in 344] over the inhabitants of Adiabenica [a Mesopotamian region]. Sometimes a storm

7.13 Nestorius and the controversy over Christ’s nature: Socrates Church History 7.32.1–7

Although the Council of Constantinople (381) (6.15) was an important step towards the resolution of the Arian controversy, another theological issue came to the fore in the mid-fifth century and generated further, and in some ways, more significant, divisions within the church. The issue at stake was how best to understand the relationship between the divine and the human in Christ. In the late 420s, Nestorius, bishop of Constantinople, appeared to be giving more emphasis to Christ’s humanity and identification with mankind, which in turn prompted concerns that he was underplaying Christ’s divinity. The moving force behind opposition to Nestorius was Cyril, bishop of Alexandria, and the eventual upshot was the holding of another ecumenical council in 431, this time at Ephesus. The passage below offers one account of how Nestorius became involved in this controversy, and although its emphasis on personal factors might suggest an attempt to trivialise his views, it does direct attention to the central issue of the term Theotokos. Many aspects of the conduct of the Council of Ephesus were less than satisfactory, but the eventual upshot was the condemnation of Nestorius. The controversy continued, however, culminating in another ecumenical council at Chalcedon in 451.

Further reading: Price 2004; Millar 2006: ch. 4; Graumann 2013; Lee 2013: ch. 7.

(1) He [Nestorius] had an associate, a priest named Anastasius, whom he had brought with him from Antioch. He held this man in high regard and used him as an adviser in his affairs. (2) One time when preaching in church, Anastasius said, ‘No one should call Mary Theotokos [‘God-bearer’ or ‘Mother of God’] – for Mary was human and it is not possible for God to be born of a human.’ (3) When they heard this, many clergy and lay people were upset, for they had long been taught to regard Christ as God, and in no way to separate the human of the Incarnation from the divine being . . . (4) After the commotion which, as I have said, happened in the church, Nestorius was quick to endorse Anastasius’ view, for he did not want a man whom he respected to be found guilty of blasphemy, so he regularly preached in church on this subject, discussing the subject in a provocative manner and completely rejecting the term Theotokos.

(5) Since others took a different view of the subject, a division developed in the church, and, like those involved in a battle at night, people said one thing, and then something different, agreeing on a point and then rejecting it. (6) Nestorius gained the reputation among many of saying that the Lord was a mere mortal and of introducing the teaching of Paul of Samosata and of Photinus into the church. (7) Such great controversy and turmoil was set in motion concerning this issue that an ecumenical council was deemed necessary.

7.14 The definition of the Council of Chalcedon: Acts of the Ecumenical Councils 2.1.2, pp. 129–30

After two decades of Christological controversy following the Council of Ephesus, the death of the long-reigning Theodosius II offered the opportunity for another attempt to resolve matters, which the new emperor Marcian took by agreeing to another ecumenical council, this time at Chalcedon, across the Bosporus from Constantinople. The council attempted to square the circle with a very carefully worded definition of faith which tried to satisfy all parties, but with an underlying emphasis on unity rather than duality in Christ. However, those loyal to the memory of Cyril and to the position which he had championed at Ephesus considered that the definition made too many concessions to the Nestorian position, and instead of Chalcedon acting as a catalyst for unity, it became an obstacle to achieving that goal.

Further reading: Chadwick 1983; Price and Gaddis 2005 (which includes a translation of the acts of the council); de Ste Croix 2006: ch. 6.

Therefore, following the holy fathers, we all unanimously teach confession of our Lord Jesus Christ as one and the same Son, the same complete in divinity and the same complete in humanity, truly God and the same truly man, having a rational soul and body, consubstantial (homoousios) with the Father in respect to divinity, and the same consubstantial with us in respect to humanity, like us in all things except for sin, begotten from the Father before the ages in respect of divinity, and the same in the last days for us and for our salvation from the Virgin Mary the Mother of God (Theotokos) in respect of humanity, one and the same Christ, Son, Lord, Only-begotten, acknowledged in two natures without confusion, without change, without division, without separation – the distinction of the natures is in no way destroyed by their union, but rather the distinctive properties of each is preserved and brought together in one person and one inner entity (hypostasis) – neither separated nor divided into two persons, but one and the same Son, Only-begotten, God, Word, Lord, Jesus Christ, even as the prophets of old and the Lord Jesus Christ himself instructed us about him, and the creed of the fathers has handed down to us.