8. Financial Affairs

For the most part, actors resent paying agents’ commission. They don’t mind paying their accountant or their doctor, but they do mind paying their agent. Or, indeed, paying for anything else involving agents. ‘Can the agency pay for this?’ says the actor to the agent, conveniently forgetting that the agency will be paying the restaurant bill from its 10 per cent, rather than from the actor’s 90 per cent. Over the years, I have come across many restaurant bills that curled up on the table until I finally picked them up. Many actors accept commission as a part of life, but a few will go to any lengths to avoid it.

One such was Leslie Phillips. I had known Leslie for many years and thought that he was brilliant at what he did, but I was never convinced that he possessed quite the range he thought he had. I was always suspicious of using comic actors in serious parts - was it rather gimmicky? I looked after Jimmy Jewel, of Jewel & Warris fame, after he’d had a great success at the National in Trevor Griffiths’s play Comedians. Jimmy then thought he was a proper actor, but I was never so sure. I think the problem using comics in so-called ‘straight’ parts is that the persona of the comic is usually stronger than that of the character he’s playing. Norman Wisdom, Bob Monkhouse or Russ Abbott going ‘legit’ never quite works for me.

Leslie Phillips wanted to put his Carry On image behind him; no more lecherous dentists or randy car salesmen for him: he wanted to go to the National Theatre or the RSC and do some proper acting. Julian and I said we’d give it a try. And we did. We tried and tried and tried, and finally we got an offer for him to join the National. Leslie was very excited at the prospect until I told him what the money was.

‘I couldn’t possibly do it for that,’ he said. ‘Go back and get some more.’

I explained that the money was their ‘special top’; not just their ‘top’ but their ‘special top’ - topper than top. Gielgud money. McKellen money. Dench money.

‘Well I’m sorry, I couldn’t possibly do it for that.’

So Leslie didn’t go to the National, or the RSC, or anywhere else. But he did make it clear to Julian and me that he was looking to move his career in a different direction. He’d even shave off his moustache if necessary.

A few weeks later, the theatrical producer, John Gale, sent me a new play by Michael Pertwee called Sextet. The plot centred on yachts, ex-wives, mistresses, philandering and general marital mayhem. John was very keen for me to send the play to Leslie. I explained that Leslie’s career was moving in a different direction, and that playing a randy, philandering yachtsman was not it. But I promised to pass the play on to him, without holding out any hope that he would be interested.

Leslie was upset. How could I have sent him a play about a randy, philandering sailor? I knew that he wanted to move his career in other directions - Anouilh, Brecht, Chekhov, Moliere, Pinter, Rattigan and Stoppard. These were the kind of writers with whom he wanted to be associated, not Michael Pertwee. He was annoyed and hurt that I had completely ignored his instructions; so hurt, in fact, that he saw no point in continuing our professional relationship. He was leaving me. ‘No great loss,’ said Julian. ‘I thought the play was terrible. Imagine if he’d wanted to do it; we’d have had to sit through the bloody first night and buy him dinner afterwards. A blessing in disguise.’

I wrote Leslie a charming letter, expressing my regret and disappointment, wishing him luck for the future and asking him to let me know when he was fixed up with a new agent so that I could forward his post. And I let John Gale know that Leslie, as I had suspected, wasn’t interested in Sextet.

A few weeks later, I had another telephone call from John. Would Dinsdale Landen be available for Sextet? I said that he was technically free, but wasn’t he a touch on the young side for the raunchy old seadog?

‘It’s not for that part,’ said John, ‘it’s for the friend.’

‘He certainly wouldn’t be interested in playing the friend,’ I replied. Nobody’s ever interested in playing the friend. ‘But I’m sure he’d read the other part.’

‘That’s cast, I’m afraid.’

‘Who with?’

‘Leslie Phillips.’

John explained that he had been surprised when Leslie had telephoned him direct. Leslie had told him that I was no longer his agent, and that he had decided not to engage a new agent for the time being. Nevertheless, he would like another look at Sextet.

‘I did a deal with him, and he opens in the play in a couple of weeks.’

It ran in the West End for eighteen months, and Leslie paid us - naturally - no commission.

Although Derek Nimmo carved out a career playing dippy clerics, there was nothing dippy about him in reality. He ran a very profitable company producing plays on a tight budget for expats in the Middle East. Ray Cooney in Abu Dhabi was just what they wanted to see. I was in Sydney when Derek was starring in a play called Why Not Stay for Breakfast? We met for the first time over dinner. He asked me what kind of deal I was on at my hotel. I explained that I was a guest of a film distribution company, so everything was being picked up. Derek’s bill was also being paid, but theatrical producers work on rather tighter budgets.

‘Do they pay for your laundry?’ asked Derek.

‘Well I guess they do, but I’m moving on to Hong Kong tomorrow, and I haven’t really got any.’

‘Do you mind if I put some of my laundry on your bill before you go?’

I was rather taken aback by this idea. I hardly knew Derek and wasn’t desperately keen on getting acquainted with his laundry.

‘What time’s your flight?’

The following morning as I was eating breakfast in my room there was a knock on the door. It was the maid with an enormous basket of clothes.

‘This is from Mr Nimmo,’ she said.

A few minutes later there was another knock and a different maid.

‘I believe you have some laundry, sir.’

She removed the basket. And when I signed the bill, there it all was, under sundries.

At the other end of the scale was Kenneth More. When Kenny More was in the early stages of Parkinson’s disease, an illness that was to take his life far too quickly, he was offered a part in a film with which initially he thought he could cope; but the anxiety of it all made him change his mind and he had to withdraw. The producers were sympathetic, although I didn’t go into much detail about his illness, as he was still hopeful of a recovery.

‘The money would have been nice, darling,’ he said to me. ‘I’m sorry to have let you down.’

A few days later he wrote to me, saying how disappointed he was not to have been able to cope with the film and enclosed a cheque. I telephoned him and asked what the cheque was for.

‘It’s for your commission, darling,’ he said. ‘I don’t see why you should be out of pocket just because I’ve had to pull out of the film.’

I tore the cheque up, not something I was in the habit of doing, but I never forgot his generosity. Sadly, he died soon afterwards at the tender age of sixty-seven.

In addition to our other duties, Julian and I had to buoy up our clients. Apart from a very few exceptions, actors enjoy working and when they’re not working they need buoying up. Buoying up is an important part of the agent’s stock-in-trade. I remember John Le Mesurier was in a play which was creaking to an early death in the West End, aided by some terrible notices and even worse performances. John had been out of work for months before the play opened and was counting on a decent run to sort out his ever-delicate finances. Unfortunately, the night I went to see him, the theatre was virtually empty and one or two of John’s fellow performers were not quite on top of their lines. As I was ushered into his dressing room, I was struggling.

‘What about you, then?’ I said. (Always a good, though insincere, standby in an emergency.) John was the best thing in it, but that didn’t really say much.

‘Did you enjoy the play?’ he asked. Now actors always ask you if you’ve enjoyed the play that they’re in and the answer to give is obviously ‘yes’. It’s always best to be enthusiastic, but not overly so: Julian’s rather over-the-top standby was ‘It was the best play I’ve ever seen.’ If I had used that one on John he would have thought I was taking the piss.

‘I don’t know what to say, John,’ I replied. ‘What an amazing evening.’

So far so good.

John then told me that the notice had gone up that evening and the play would be off by the end of the following week.

‘Are there any other jobs in the pipeline?’ he enquired. Of course, there weren’t. I’d hoped he’d be in the play for at least six months, or maybe longer.

‘Unfortunately not, but I’m sure once people hear you’re free...’

I then had a flash of inspiration and remembered an apt phrase which a fellow agent had passed on to me. ‘To be honest, John, I’m jolly pleased the play’s coming off, because, to an extent, you’re no good to me when you’re working. I can’t put you up for jobs; there are no contracts to negotiate; no photos and CVs to bike over to casting directors and producers. No deals to make. Do you know what your greatest asset is to me, John?’

‘No,’ he replied.

‘Your availability!’

Before I left I spoke to Fred, the ninety-year-old stage doorman.

‘It was quiet as a grave in there,’ he said. ‘And it’s supposed to be a comedy, isn’t it?’

Fred had been stage doorman for over seventy years and was renowned for these pithy bons mots. Producers would often let him read plays before they optioned them; after all, he’d seen a lot more of them than they had.

‘You must have some amazing memories, Fred,’ I said, ‘all those years here, all those comedy legends. What were they like?’

‘I saw ‘em all, Michael,’ he replied. ‘Vesta Tilley, Little Titch, Marie Lloyd, Harry Lauder, the lot.’ He paused. ‘And shall I tell you something, Michael?’

‘Yes, please, Fred.’

‘Do you want me to be completely honest?’

‘Yes, Fred.’

‘They were all fucking awful. Every one of ‘em. Give me that Richard Briers any day.’

Within a week of the play coming off, John had been offered another job. I think I had buoyed him up. I remember him telling me that his previous agent, Freddie Joachim, had told him, ‘Don’t make yourself too easy to get. Say no from time to time. It keeps producers on their toes.’ That was all very well for Freddie, but John needed the work and hated turning things down. ‘I always thought that Freddie viewed me as a Second XI client,’ said John. ‘On the very rare occasions he took me out to lunch it was never the Ivy, always the cafeteria at Bourne and Hollingsworth.’

John was the sweetest of men, tailor-made for the part of Sergeant Wilson in ‘Dad’s Army’. I remember working on a stall at a charity fete with him. A man pushed forward and pulled his sleeve.

‘Are you who I think you are?’ the man said. ‘What’s your name?’

‘I’m sure it will come to you,’ said John.

The man returned five minutes later. ‘I know who you are!’

‘Jolly good,’ said John.

‘You’re Daphne du Maurier.’

‘I’m afraid I’m not,’ said John dejectedly, ‘but I certainly wish I was.’

Another client, Donald Sinden, was also the master of the self-deprecating story. A favourite of mine was when he was working with Judi Dench at the RSC in Stratford, playing Benedick to her Beatrice in Much Ado About Nothing. The play opened to rave reviews and Donald was feeling very pleased with himself. Walking along the river on his way to the theatre one afternoon, two pretty girls approached him.

‘Please, please may we have a photograph?’

Donald puffed out his chest.

‘Of course. Where would you like it? In front of the theatre, or with the river and swans in the background?’

‘By the river please.’

They walked to the river, chatting amiably about the fine spring weather.

‘Here will be perfect,’ said one of the girls.

Donald preened. The other girl handed him a camera. ‘It’s quite easy to operate. Just press this button.’

Donald took two photographs of the girls and then, somewhat deflated, headed for the stage door.

I discovered early on in our partnership that Julian kept rather eccentric hours. I quickly fell in with his routine, despite the potentially lethal consequences to my health. We would arrive in the office between 10.30 and 11a.m., and have a cup of coffee together to discuss the day’s social arrangements, which would usually include lunch at the Turf Club. It only dawned on me after a few months that our choice of offices in St James’s Street was based entirely on their proximity to Carlton House Terrace. When I later suggested a move to Chelsea, our first lease having run out, Julian made me feel as though I’d suggested relocating to Peckham. At 12.45, Julian would saunter into my office to where the drinks cabinet was located - it was mutually agreed (and probably safer) that the cabinet would be located in my office, rather than his, as mine was the better office in which to entertain - and pour himself a large gin and tonic. We would then stroll down to the Turf, have a few drinks at the bar and settle down to lunch at 1.45. White wine with the starter, a carafe or two of red with our main course and cheese; then back to the bar for coffee and a couple of kummels on the rocks, before returning to the office at around 3.30. Julian would then take a catnap or watch the racing on television. Cries of ‘Come on my son!’ would indicate that his investments were paying off; silence would suggest the opposite. From time to time the telephone would ring. At 5.45, Julian would return to the drinks cabinet for an early-evening scotch and then head back to the Turf for his evening’s entertainment. I, on the other hand, would go home and place a damp towel across my head.

Needless to say, the Turf was Julian’s second (and spiritual) home, where he was much loved and respected by members and staff. One year the Turf decided to convert some unwanted rooms into bedrooms, a transformation warmly received by the members. (No more expensive hotel rooms for country members, or long, drunken drives home after dinner.) Once the bedrooms were put into service, they proved so popular that the committee agreed to bend that most sacrosanct of rules and allow members’ wives to share their husbands’ rooms.

Seeking to take advantage of the new arrangements, Julian had a quiet word with the head porter, Grace, about the new accommodation.

‘Does that mean we’ll be able to bring our girlfriends to stay in the club, Grace?’ asked Julian.

‘Indeed, sir,’ replied Grace, ‘provided, of course, your girlfriend is the wife of a member.’

Julian put me up for the Turf, but I felt rather out of my depth there, having no particular interest in racing. Instead I joined the Garrick Club, which was more up my street. Don Taffner, the American television producer, once told me about a visit he had made to the Garrick. Two of the club’s members had invited him to dinner, and as he arrived ahead of them, he was shown upstairs to the Morning Room. As he sat there alone, admiring the paintings, through the door walked Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother. Immediately, Don sprang to his feet. The Queen Mother, surprisingly unaccompanied, offered him an outstretched gloved hand.

‘Don T-Taffner, Your M-Majesty,’ he stuttered, attempting a bow.

‘Good evening, Mr Taffner,’ she replied, at which point two men appeared behind her.

‘Ma’am, we’re in the room next door.’

She gave Don a sweet smile and disappeared into an adjoining room, where she was attending a private party.

Over dinner Don found his two hosts on the patronizing side. ‘I bet you don’t have anything like this in New York?’ ‘What about these paintings, eh?’ At the end of dinner Don said that his visit to the club had been a memorable occasion and one that he would always cherish. As they were walking from the dining room to the main entrance, the Queen Mother came down the stairs.

‘Look Don, it’s the Queen Mother,’ whispered the member. ‘She comes here quite often,’ cooed his friend.

As she passed, she gave Don another gleaming smile.

‘Good night, Mr Taffner,’ she said.

‘Good night, Ma’am,’ he replied.

His hosts pulled themselves up from their deep bows and looked at him in amazement.

‘What a great lady,’ said Don.

As a lover of four-legged animals (slightly preferring them to the two-legged variety), Julian was keen that Leading Artists should be represented on the turf. The Winner and Sporting Life always took pride of place on the reception coffee table, well ahead of the Hollywood Reporter and Screen International. One day our accountant, Ron Parker, mentioned that we might be able to get some of the running costs of a racehorse through the company’s advertising budget; but suggested that we should start on a smaller scale, perhaps with a greyhound. Julian, being a regular visitor to the Wimbledon dog track, was delighted. He met up with a trainer he knew called Randy Hamilton, and returned to the office with the news that we now owned a greyhound called ‘Leading Artist’. The dog cost a modest sum - five hundred pounds - but it clearly had a less than modest appetite, judging by the monthly food and board bills we paid. Leading Artist had never run professionally when Julian handed over our cash; so it was up to Randy to train the dog for a year and then decide if it would be good enough to race. Julian made a visit to Randy’s training establishment somewhere in Essex and reported back that Leading Artist was looking fit and well.

‘“By the end of the year, we’ll be in the winner’s enclosure at Catford”’

‘Did he know he was called Leading Artist?’ I asked. ‘Did he lick you like dogs do to their masters; was he pleased to see you?’

‘Don’t be ridiculous,’ said Julian.

‘What did he look like?’ I asked.

‘Like a bloody greyhound.’

‘What, you mean grey and thin?’

‘Exactly.’

‘Well, judging by the amount of money Randy’s charging us for food, I’m surprised he doesn’t look like a fucking St Bernard. And, anyway, how did you know that it was Leading Artist and not just any old dog?’

‘Well I didn’t. But Randy was very positive, said he was doing really well and that by the end of the year we’d be in the winner’s enclosure at Catford.’

Six months later Randy reported that Leading Artist hadn’t made the grade after all; he was reluctantly going to have to put him out to grass. He submitted his final bill, which included a charge for rehousing, and we never heard from him again, not even a Christmas card. I wondered whether Leading Artist ever really existed, or was he the four-legged embodiment of all Randy’s corporate clients owning a greyhound? Was Rover not only Leading Artist but also Curtis Brown, John Murray and William Morris? Had Julian fallen for the three-card trick like my father had with those doves?

The following year we bought a racehorse and Julian persuaded Nick Gaselee, one of the Royal Family’s select group of trainers and a Turf Club chum of Julian’s, to train it. Now we were into serious money. Randy wouldn’t have been able to afford a hoof, let alone a leg. Up to this point, I had traditionally put a pound each way on a few of the horses in the Grand National in the vain hope that one would win, and left it at that. Now Julian moved me into a different league, into a world of ‘yankees’, ‘bet doubles’ and ‘accumulators’. And the pound each way bet had turned into £100 to win. ‘Put it on the nose,’ Julian used to say. ‘Each way is a loser’s bet.’ Julian endlessly told me what he had ‘stood to win’. Sometimes it was £1,000, sometimes as much as £5,000. But I quickly realised that ‘stood to win’ meant that he had lost his original investment of several hundred pounds, so it wasn’t quite as impressive as it sounded. Julian was always saying to me, ‘Help yourself!’ This meant that the bet was so rock solid that it would be churlish not to make a substantial investment. I fell for this kindness a couple of times, but without success, and then decided to leave Julian to help himself and leave me out of it.

Nevertheless, I did back Leading Artist - for that was his name - up to the hilt, until Julian told me not to help myself. Poor old Leading Artist had come nowhere in his first four starts and Nick Gaselee was recommending moving him on. His next start took him to Towcester, a race in which I was pleased not to have any financial involvement.

Over the weekend of the race, I was staying at the Blakeney Hotel in Norfolk (a far cheaper proposition than spending it at the races). Lying in my bath on Sunday morning, I took a cursory glance at the racing results and was surprised to see Leading Artist’s name in bold print. What did this signify, I wondered? The answer was that the horse had won, and not just won, but had won at odds of 100 to 1. I leapt out of the bath and called Julian.

‘It was fantastic,’ he said. ‘All the horses fell bar two and Leading Artist pissed up.’ ‘Pissed up’ was another of Julian’s favourite euphemisms. ‘I took John Hurt with me and we both cleaned up. It was the first time a horse has won at 100 to 1 at Towcester since the 1930s.’

Sadly Leading Artist never won again, and Julian ‘moved him on’.

To keep control of the ebb and flow of money coming in and going out of the office, an agency needs the services of an efficient bookkeeper. David Callaghan was an eccentric character and an excellent bookkeeper. He was efficient, hard-working, good at talking to actors and, most important of all, honest. After working with Terry Plunkett Greene and Julian, he worked for Leading Artists and ran the accounts department for many years before deciding he needed a change of scene. His departure gave Julian and me quite a shock: bookkeeping was certainly not our forte, and we tended to sign anything put in front of us.

Julian, however, had an even lower boredom threshold than I. His eyes would always glaze over during our company AGM, which he used to arrange at midday so that we could be at the Turf Club bar within the hour. After some searching, a lady called Yanka was engaged to take over from David. An intelligent, middle-aged woman, she had one major deficiency, which, it soon became clear, would end our relationship within weeks rather than the years for which I had hoped. Her problem was that she had a propensity for asking questions, to which Julian never knew the answer and cared even less.

‘Do you keep the cashbook up to date on a daily or weekly basis?’ she enquired.

‘Do you sign one another’s petty cash slips?’

‘Do you like a mixture of notes and coins in the petty cash box?’

‘Do you have a separate VAT account for your entertaining?’

‘Do you mark personal items on your credit card bills?’

‘Do you happen to know Daniel Day-Lewis’s National Insurance number?’

‘Is VAT payable on this contract?’

‘Is Judi Dench a company and, if so, what is the registered number of the company?’

All perfectly reasonable, but this was an area of the business that held little appeal for me, and for Julian none at all. Indeed, it made him very cross. The more cross he became with poor Yanka, the more questions she asked, and her office was nearer to his than mine. She was endlessly walking in with ledgers, files and balance sheets, trying to get Julian’s attention away from the 3.30 at Sandown - usually unsuccessfully. I used to keep my door firmly closed. If she ever happened to ease it open, I would grab both telephones off my desk and pretend I was on a hugely complicated three-way international conference call. ‘Hang on a second, would you, Dimitri?’

It was clear that we would soon be talking of Yanka in the past tense. On one Friday afternoon, after Julian had had a particularly good lunch and was snoozing in his favourite armchair, Yanka walked into his office with a pile of VAT receipts she wanted to discuss with him.

Julian exploded. ‘Madam, I have no interest whatsoever in your VAT receipts, or indeed in anything else you could possibly have to say to me. You’re a crashing bore. I suggest you take your ledgers and your balance sheets and go fuck yourself!’

Yanka rushed into her office in floods of tears; moments later she was in front of my desk.

‘I’m sure Julian didn’t mean to be rude, Yanka. It’s just that he does get easily bored with VAT.’

‘I’ve done my best, but I can’t take any more. I’m giving in my notice.’

I was hugely relieved, although the prospect of finding another bookkeeper filled me with horror.

‘Oh really, Yanka? Well, of course, I do understand.’

Julian, of course, apologized to Yanka and even offered her a scotch, which, unsurprisingly, she declined. She left us a couple of weeks later.

‘Christy Roche’s sister,’ said Julian. ‘Perfect for us.’

Julian had been given the number of someone in Ireland who happened to know Christy Roche, whose sister just happened to be a bookkeeper.

‘Really nice girl, lives in London, and is apparently looking for a bookkeeping job. We could have fallen on our feet here.’

I had no idea who Christy Roche was.

‘Just one of the top Irish jockeys of all time, in my humble opinion,’ said Julian. ‘I think we’re bloody lucky to have his sister working here.’

I wasn’t sure that having a brother who was a top Irish jockey was necessarily a good thing in a bookkeeper - bookmaking maybe. Anyhow, the following morning Helen Roche arrived for an interview. After Julian had run through Christy’s career, enquiring about his recent rides and any hot tips circulating around the Irish racing community, we got on to our requirements.

Helen was of leprechaun proportions and very Irish. She seemed to grasp immediately what was needed and, although she had never worked for a theatrical agency before, she had looked after the accounts of a number of small businesses both in England and in Ireland. She gave us the names and addresses of two referees, and told us she could start as soon as we needed her. She never mentioned VAT.

‘Perfect,’ said Julian, after she’d left. ‘She’s just what we’re looking for. Let’s offer her the job.’

‘Shouldn’t we check out her references first, just to see if she’s any good?’

‘Well do it quickly; we don’t want to lose her.’

I telephoned her first referee, who gave her a sparkling review but turned out to be a relation rather than a former employer. The second referee had used her on a temporary basis in London and had found her honest and trustworthy. Julian was very eager to get everything fixed up; she seemed fine, given Yanka’s sudden departure.

Helen could not have been more different from Yanka. Julian was certainly pleased; he would look through the accounts department glass door, smile at Helen and then beam at me. ‘Wonderful. See the way she just gets on with it. Not all those bloody stupid questions that last woman kept asking.’

Indeed, Helen did get on with it. Her work was always efficient and well presented, and she quickly got the hang of how everything worked. At the end of each week she would bring in a large folder of cheques and statements for either Julian or me to sign. The cheques were mainly payable to our clients, less the agency commission; the rest payment of various bills and, of course, salary payments. Not complicated work, but requiring some expertise in the workings of an agency, which she seemed to acquire very quickly.

And then, after she had been with us for three months or so, she didn’t appear in the office. I called her home number - she lived in a flat in Chiswick - which was answered by a man claiming to be a friend of hers. He said she was ill, but would call later in the day. No call.

The following morning I rang again, and there was no reply. One of the girls in the office said she would go round to her flat on her way home, but called me that evening to say there was nobody there. I rang Helen’s number a couple of times that evening but still there was no reply. The following day, Julian got his racing contacts on to the case and heard back from Ireland, via Christy Roche, that he hadn’t heard from his sister for some weeks but that she was working in London. Nobody had any contact numbers for her.

I now began to wonder whether Helen ‘getting on with it’ involved more than we had bargained for. I called our accountants and they came to the office straight away and went through all the books. Everything seemed to be in order. All the money had come in and gone out in the normal way. All cheques, signed by us, were payable either to known suppliers or named clients. Maybe we were being overly suspicious.

‘Unlikely Christy Roche’s sister would be on the fiddle,’ said Julian.

And then, as Ron Parker had a final look through the books, the penny dropped. Well in fact £15,000. ‘What she’s done is clever,’ said Ron, ‘and, knowing your predilection for signing anything that’s put under your noses, foolproof - if you’ll pardon the expression -although only up to a point. She’d embarked on a scam that would ultimately be found out, though not for some time. I’m surprised she did a runner quite so soon.’

‘So what exactly did she do?’ asked Julian.

‘Well, it’s like this. As you know, you have two main accounts: your office account, which has all your commission in it, and your client account, which has all your clients’ money in it. Every week your bookkeeper transfers your commission from the client to the office account, and then transfers all the client money to the artists in question. She presents you with the cheques to sign, made payable to the various clients. The cheques, from the office account, pay the salaries, bills, rent et cetera. When you were signing a cheque for £1,000 made payable, to say, Angela Thorne, you assumed, quite reasonably, that the money would be going from the client account into Angela Thome’s account. Often it was, but occasionally it was coming out of the office account. Therefore your money, and not hers, was going into Angela Thome’s account.’

‘So was this just inefficiency?’ Julian asked.

‘Sadly, more than that, Julian,’ said Ron. ‘Because the Angela Thorne account wasn’t the actress’s account but an account opened in that name by Helen. She opened several accounts in various actors’ names and, over a period of three months, managed to steal £15,000 of your money. So when you said, “she just got on with it”, Julian, that’s precisely what she was doing. Getting on with stealing your money.’

‘Well, at least she wasn’t stealing our clients’ money,’ I said.

‘If she’d done that, you would have found out very quickly. Actors tend to know when they have money due. You and Julian were a softer touch.’

‘Charming,’ said Julian.

Sometime later Helen was arrested for operating a similar fraud and ended up behind bars, but we never got our £15,000 back.

Our next bookkeeper was Stephen Scutt. His first few weeks were tricky, since Ron had told us to be more watchful about what we signed, and to show a bit more interest in the day-to-day running of the business.

So when Stephen would come into my office with a folder of statements with cheques attached for my signature, I was more exacting.

‘Is this for a repeat?’ I would ask.

‘Yes,’ Stephen would reply, ‘from the BBC.’

‘Where does it say BBC?’

‘Here on the statement.’ He would point to three huge capital letters saying BBC.

‘Four hundred and fifty pounds, eh? What was the original fee?’

‘Well, I’d have to look at the statement from the BBC. Do you want me to?’

‘Yes, maybe just to be on the safe side. And while you are at it, is that Dan’s address?’

‘Yes, as far as I know.’

‘Has he moved recently?’

‘I don’t really know, Michael. I don’t actually know who Dan is. Remember I’ve only been here a week, and the company I was with before imported leather goods from Spain.’

‘Yes, of course. Well, I’ll check that with Julian, but let me know what the original fee is.’

‘Now what’s this? John Hurt’s profit participation in The Elephant Man? Is that all he’s got? It should be much more than that.’ And so it went on.

Of course, after a few weeks, things were back to normal, and Stephen was in and out of my office in the time it took Julian to pour himself a large gin and tonic.

Stephen ended up working for me for over twenty years, organizing the daily flow of monies in and monies out.

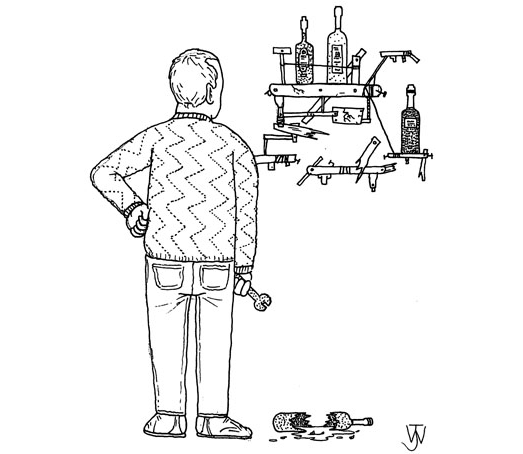

A bachelor, he lived in Chiswick and had a penchant for DIY. The most accident-prone person I ever met, he would arrive in the office with terrible stories of dreadful self-inflicted disasters, risking life and limb in the hopeless cause of do-it-yourself.

Like the time he decided to put up some wine racks to house the dozen bottles of vintage port that generous clients such as Richard Griffiths, Angela Thorne and Nigel Havers had given him over the years. He bought a wooden twelve-bottle wine rack and attempted to solve the problem of the lack of a cellar in his house by rather bizarrely putting this wine rack in his loft. One Sunday morning, with a casserole bubbling in the oven for his lunch, he opened the trapdoor of the attic and from the top of a ladder heaved his portly frame into the loft. He then fixed the rack to the wall with a series of nails and stood back to admire his handiwork. All very satisfactory. He then carefully carried up the bottles of Warre’s 1970, Dow’s ‘74, Taylor’s ‘80 and Cockburn’s ‘82, and placed them lovingly into the racks. He shut the trapdoor, removed the ladder and went downstairs to have his lunch.

As he removed the casserole from the oven, there was a loud crash and by the time he got back upstairs the top-floor ceiling was bright red and large dollops of port were dripping on to the carpet. He grabbed the ladder and, as he opened the loft door, port flooded out, covering him from head to foot. The rack had come off the wall and lay dejectedly on the floor. The front doorbell rang. He looked out of the window. It was his elderly lady neighbour. As he opened the front door the woman screamed. He caught his reflection in the hall mirror. His hands were bright red and dripping with the port and he had a gash across his cheek from a piece of broken bottle. His neighbour didn’t speak to him for months.

The port-stained floor gave him a good reason to have the house re-carpeted. He had lived there for ten years and it was in need of a freshen-up. Admiring the work of the carpet fitters after their departure, Stephen noticed they had not carpeted a small airing cupboard next to his bathroom and the bare boards offended him. With some of the off-cuts they had left behind, Stephen nailed down a strip of carpet, checked that everything was in order and decided he deserved a pre-lunch drink. Again this was a Sunday morning and his weekly casserole was simmering away. As he walked across his sitting room, a jet of boiling hot water shot across the room. This was quickly followed by another jet of water from the opposite side of the room, criss-crossing the first one, like some opulent water feature. Stephen was drenched. As the room began to steam up, he grabbed the telephone and rang his plumber. The plumber had just got back from the pub and was rather the worse for wear, but Stephen managed to talk him into coming over. The drunken plumber turned everything off and in an attempt to sober up joined him for a plate of his casserole. He subsequently discovered that Stephen had nailed through a vital pipe in the central heating system. What was this thing about Stephen and nails?

Nails came into play again a year or so later when he put up some shelves in the living room of his new house. The shelf unit between his kitchen and dining room was a large four-tiered affair in pine. Checking carefully that it was securely fastened, he filled it with books on three shelves and on the top fourth shelf placed his collection of rare porcelain figures. He stepped back yet again to admire his morning’s work. The antique leather-bound books set off the delicate porcelain figures and his most prized possession, a Meissen harlequin, formed a fitting centrepiece for this elegant display. He went into the kitchen, closing the door behind him; the oven was smoking and he didn’t want cooking smells in the sitting room, as he had friends coming for tea. As he lifted the casserole on to the kitchen table and started to serve himself with a generous portion, there was a deafening crash from outside the door. He pushed the door but it wouldn’t open. The shelves had fallen off the wall on to the floor, followed by the books and porcelain, and had banked up against the door. He climbed out of the window but had no latch key to get him back into the house, so he was forced to smash a window into the sitting room, where he was confronted by the full horror of his hopeless handiwork.

The loss of his porcelain collection forced Stephen into abandoning his DIY aspirations once and for all. Leave it to the experts would be his motto. Well, apart from fixing to the wall of the garage his father’s antique Victorian toolbox, which had sat gathering dust on the floor for many years. He fixed two smart brass brackets on to the plugged walls and then lifted the heavy box on to them. It looked very handsome and he was glad that for once he had used screws rather than nails. As he leant back to get a good look at the whole effect, the box sprang off the brackets and hit him on the chest, forcing him back on to the bonnet of his car. He struggled to free himself and as he slipped from beneath the box, he saw it crash down on to the bonnet, causing what subsequently turned out to be over £1,000 worth of damage. He also discovered that he had two badly cracked ribs and it was several weeks before he was able to lift another casserole dish into the oven.

‘A bachelor with a penchant for DIY’

By the summer of 1985, I was beginning to tread water again: was it time to move on? I was finding that one of the problems with being an actors’ agent was the almost total lack of any direct involvement in the creative process. OK, so you’d read the odd script and give the actor your opinion as to its merits, but that was about the full extent of it. Although I wanted to carry on as an agent, I also wanted to become involved in the production side of the business, developing ideas and scripts for television and presenting plays for the theatre. I discussed my aspirations with Julian. Would he also be interested in getting involved with that side of the business?

‘Not my cup of tea, old boy,’ he said. ‘Conflict of interest: you can’t be an agent and a producer. Wouldn’t work. All the clients would leave.’

I thought this was a rather sweeping appraisal of the situation, though Julian’s response was not unexpected. He found being an agent professionally fulfilling. I, on the other hand, didn’t, even though actors were more integral to my personal life than to his.

My friends tended to be, if not my clients, then certainly people in or around the business. Julian was completely different. ‘I simply can’t understand how anyone could possibly want to see Peter Bowles on a Sunday,’ he’d say, with incredulity. His friends were mainly fellow members of the Turf Club, racing people or those with an interest in horseracing. He had good relationships with his clients, and would defend them to the hilt; but evenings (apart from first nights) and weekends were his time, not theirs.

Julian most probably had it right. Even as their agent, I sometimes expected my clients to be like the characters they played on stage and screen. Some were, but most weren’t. The suave, sophisticated matinee idol is usually racked with insecurities, not remotely sophisticated, and invariably a lot less suave than he pretends to be. Comedy actors seldom sit around dinner tables cracking jokes. And the hard man of films and television drama is often a softy underneath. Actors tend to be mercurial, multi-layered people, like those Russian dolls, and one never quite knows whether one is talking to the real person or whether there are a few more layers underneath.

David Lean thought too much intelligence in an actor was a bad thing. When he was making A Passage to India with Nigel Havers and James Fox, he was directing a long shot of Peggy Ashcroft outside the Marabar caves. He wanted her to look across towards the cave and point. He sent her a message via his first assistant. The response came back from her on the walky-talky, ‘Dame Peggy wants to know why she is pointing towards the cave.’ David blew his top, and told his first assistant to tell her that David wants her to point at the cave because he’s told her to, and she’s a fucking actress and he’s the fucking director. The diplomatic first assistant presented Sir David’s compliments to Dame Peggy and said it would help him hugely with a linking shot later in the sequence. ‘God protect me from intelligent actors. All one wants is for them to be able to act and do as they’re fucking told,’ said David.

I had been with Julian for ten very happy and profitable years, but I felt I needed a few new challenges and my liver was also telling me it was time for a change. I dreaded telling Julian, as I knew he’d find it incomprehensible, which he did. The divorce was amicable: no custody battles over clients and no alimony payments. It was pretty clear who was going with whom; the financial side of the business was divided neatly; and Julian was happy to take over the lease of 60 St James’s Street. I was equally happy to flee the temptations of St James’s and start leading a more sheltered existence in South Kensington.

Our assistant, Amanda Fitzalan Howard, came with me, as did Stephen Scutt, although I declined his offer to help with the refurbishment of the new offices at 125 Gloucester Road, next door to the Gloucester Road Bookshop. The day we moved in I noticed a book, which I subsequently bought, in the shop window; it was A Madman’s Musings by ‘A Patient during his Detention in a Private Madhouse’. Was this an omen?