2013 rally (photo by Ted Eytan, MD, Washington, D.C.).

Jules Chyten-Brennan

FOR SOME OF US, SURGERY is a natural step in our process. For others, it is never part of the plan. No matter what we ultimately decide, most of us at least grapple with the question of surgery because of our own or others’ curiosities about it. It is often assumed that every trans person desires surgery, and that without constraints it would be a matter simply of when, not if. Truthfully, however, each of us relates to our body differently and makes individual choices to best suit our needs. We may have many surgeries or no surgeries, and it is important to recognize that each decision is just as right as the next.

There are a variety of terms used to describe transgender-related surgeries. Some of these include gender-affirming surgery (GAS), gender reassignment surgery (GRS), sex reassignment surgery (SRS), and gender-confirming surgery (GCS). These terms are often used interchangeably as umbrella terms that encompass all possible procedures undertaken in the process of surgical transition. In some contexts they are used specifically in reference to genital surgeries.

For some of us, surgery may be extremely important to our sense of self, while others of us never wish to have surgery. For many more of us, our feelings lie somewhere in between, and we must evaluate personal desires and logistical supports and constraints.

“I didn’t so much decide to have this surgery as I felt I could not go on living without it.”

“I have no desire to surgically modify my body because I would like to find a way to become comfortable with my body as it is.”

“I’ve known even since before I started identifying as genderqueer that I didn’t like my breasts. They were big and didn’t look good, and were of no use to me. I wanted to be able to wear clothes that didn’t hide my body, and to be able to take my clothes off without my body sending false signals about who I was.”

As trans people, we are often asked whether we have had “the surgery.” This question implies (falsely) that there is one single surgery to get and we all desire it. In most contexts, this question of “the surgery” refers to “bottom,” or genital surgery. Our surgical status as “pre-op” or pre-operative versus “post-op” or post-operative is also often used to judge whether we have “completed” transition.

Within our own communities, we also sometimes make judgments about other trans people based on the kinds of surgeries they have or have not gotten. We may believe that someone is not committed enough to being trans if they have not had particular types of surgeries.

How anyone’s gender is perceived on a daily basis is not related to our genitals at all—we never see, or even think about, most people’s genitals, and yet we manage to relate to people as a certain gender without knowing this information. However, when our trans identity is revealed, our surgical status becomes crucial to others to place us in a new box.

The curiosity and expectation about having genital surgeries also has to do with the belief that we need to be able to fulfill particular sexual roles, with either insertive or receptive sexual acts. The assumption here is that we are transitioning with the goal of becoming more heterosexual as opposed to more ourselves. This is made more explicit when trans people openly engage in same-sex or queer relationships. Confused outsiders frequently ask, “Well, why didn’t you just stay a (boy/girl)?”

Why then is it so important to know the status of a trans person’s genitals—or if we have had “the surgery?” Perhaps when the world can consider that sexual orientation and gender identity exist as natural healthy spectrums, we will not hear this question quite so often.

There are numerous factors affecting our decisions about surgery, and they are different for each of us. We may desire surgery but not be able to afford it. Some of us may be able to afford it but might not feel the likely results will meet our expectations. Many of us postpone surgery, even if we could have it earlier, because we want to make sure that other things in our life are taken care of, such as mending relationships with our partners or preserving our fertility.

Yahoo groups for learning more about surgery include ftmsurgeryinfo, MTF-SRS-FTM, ftmphalloplastyinfo, FFS-support, Finances_SurgeryFTM, TheDecidingline, and ftmmetoidioplasty.

2013 rally (photo by Ted Eytan, MD, Washington, D.C.).

The majority of gender-affirming surgeries are not covered by insurance, and so many of us have to pay for them out of pocket. Cost, therefore, is one of the most common considerations we have to take into account. For an idea of the range of prices for different types of surgeries, see the sections on each procedure later in this chapter. On top of surgical expenses, additional funds are required for medical clearance, travel, hotels, aftercare, and time off from work. For most people these are sizeable expenditures. As trans people, we are disproportionately in lower socioeconomic brackets, making the financial burden even more prohibitive.

Because of the social associations between gender and specific body parts, many of us feel uncomfortable with the standard anatomical names used to describe our bodies. Some of us choose alternate names for our body parts. Others of us separate the individual parts from their gendered associations and refer to “people with ovaries,” for example, instead of “people with female parts.” In this chapter, we largely use this second approach for the purposes of clarity. However, feel free to cross out and replace any words you do not like with your own. See Chapter 17 for more about naming our own body parts.

“I. . . have no job and have had fruitless searches for a part-time job ever since I transitioned. The thought of future medical bills and how I’ll ever pay for my vagina scares and depresses me.”

“I can’t afford surgery, and the lottery hasn’t helped me any.”

If the cost is not out of reach, the question becomes whether surgery is worth the expense, or if other priorities take precedence.

“At this time I do not anticipate having SRS. It’s not that I would mind having a fully female body (where’s that magic wand when you need it?), but I don’t feel that I want it bad enough to justify the cost and risk/discomfort of major surgery.”

Others of us feel that surgery is a necessary step toward gaining financial security. The ability to “pass” may mean more confidence in the job market and more comfort in the workplace.

“I had a thyroid cartilage reduction, partly to increase passability last year while I was looking for a new job. I didn’t want part of my appearance to be out of the ordinary and cost me a chance to work, although that surgery hadn’t previously been a big priority. I am glad that I had it done and I feel much more confident now that it’s all healed up and while I hadn’t thought it was so important, it turned out to have a really big impact on how I see myself and I wish I had considered it sooner.”

Kay Ulanday Barrett

I have always been at the cusp of different cultures. I went to a liberal university but felt surrounded by white, affluent people. This translated into the queer and transgender community. We carved queer and trans people of color (QTPOC) space, but having spaces for trans people of color was seen as too militant or as snobby, and it was dubbed as separatism or as a “gang approach.”

The mostly white, affluent people around me in school tended to have insurance, and benevolently liberal families. So much of the FTM community ushered themselves into liberal white, male, able-bodied privilege that I didn’t want to affiliate my manhood or boihood with them. I was at the cusp; in my own neighborhood I could be a kuya, butch, AG, stud, or brown boi, but out of place with my upwardly mobile language and not having to do manual labor or struggle with language barriers the way much of my blood family has.

I attended a “top/chest surgery for FTMs” workshop held at an Asian and Pacific Islander health clinic, but more than half of the attendees were white and hadn’t considered any of the negative cultural implications of white people taking up space at an LGBTQ POC organization that serves immigrant communities. That community also had a troubling, evident financial privilege. Several mentioned their insurance, or their families who could pay for top surgery, without even considering that the clinic served low-income and working-class Asians, migrant workers, and queer, trans, and HIV-positive immigrants.

This is a trend in many liberal and mainstream Asian and Pacific Islander spaces, sometimes carried out in our internalized racism. Queer, trans, and gender nonconforming people of color and low-income people in the United States have issues accessing surgery, but they also deal with concerns related to housing, the medical industrial complex, foster care, homelessness, police brutality, and more.

I am in a different place than I was five years ago, or eight years ago. When I was younger, growing up Midwestern and in a segregated Chicagoan space, forging queer, gender nonconforming, and trans person of color joy was hard, but happened on a daily basis, whether it’s your homey going with you to the Medicaid office or you asking someone to help you process your late food stamps.

When I “was” a woman of color dyke/butch/AG, white feminist womyn would call me their “sister.” That word sister rotted in me, for so many reasons. I do not feel at home with whiteness. I can no longer open my heart up to it, unless it is about redistribution of resources and not taking up space. I now see how my brotherhood, my boihood, is developed and building. I am not your little brown brother, white people. We are not starting at the same line or “in this together,” as you may say.

My body and existence—as I grow, evolve, and become—cannot be bogged down by white expectations, but must be of brown/mixed/black/of color creation and preexisting cultures. I am excited to call my homeys and hear their stories, how they felt when their Nigerian, Filipin@, Latin@, Chinese, upsouth Black boi manhoods came up.

White trans and queer people specifically, when you are taking up space in brown, person of color, mixed trans and queer communities, know that I see you. Our brown and mixed lives are not to be toured through like a vacation getaway. Just because we might hold the transgender or queer or masculine or male banner together, we are not the same.

Our loved ones have emotional investments in our bodies and life choices. The decision to have surgery may cause an emotional response in those closest to us. Even within relatively supportive relationships, there may be some apprehension caused by concern for our physical safety, fear of potential regret, or grief over a perceived loss of who we “were.” The impact on our relationships can be an important part of our decision-making process. We may grapple with the possible outcomes of our decisions and work with our loved ones to develop understanding before we take action. Some of us may wait a period of time until we have worked through some of these issues with our partners.

“Decided against top surgery due to potential loss of nipple sensation and potential impact on my current relationship.”

“My partner doesn’t seem to care if I keep it or not, and I don’t ever intend to have sex with a guy (gay or straight), so having a vagina isn’t as critical. And to be honest, at age 56, I don’t look at the issue of having the right plumbing with as much anxiety as younger trans people.”

Some transition-related surgeries alter our reproductive organs, which can affect our fertility. For some of us, knowing that we have reproductive organs that belong to a sex with which we do not identify becomes a strong source of discord. Hence, surgical removal is a high priority. Others of us choose to hold off on surgery until after we have children or store our sperm or eggs for reproductive purposes before we have surgery. Chapters 11 and 18 provide more information on fertility options for us as trans people.

“I have not had gender-related surgery except getting my tubes tied. I insisted on that because it was all my insurance would cover and simply being fertile as a ‘woman’ was humiliating.”

“Preserving my fertility is a big reason I ruled out transition (at least in the near future). I know trans men can sometimes give birth, but I’m not willing to risk it. . . I wish I could make sperm, but transition won’t give me that. I’m becoming a bit less scared of the womb and birth side of things.”

Violence against trans communities is a real threat that we are all aware of, and it affects some of us more directly than others. Therefore, some of us seek out surgery in order to be read correctly and, hence, feel safer.

“I have had MtF genital revision surgery. . . including bilateral orchiectomy, vaginoplasty by penile inversion technique and labiaplasty. . . When I began transition, the ultimate goal was always to have surgery. Because of where I live, remaining in a transitory state—living full time without surgery—was just too dangerous. . . I have been very satisfied by the results.”

“I would have had facial feminization surgery as well had it been on offer and if I could have afforded it. When I have been read in public, it has always been my facial structure that made people suspicious. Regardless of any vanity concerns, I would have been much safer with that surgery.”

Some of us, however, also avoid surgery for similar reasons, and instead we want to retain the ability to be read as our gender assigned at birth.

“I must present as a male in my career, so I have deferred any decision on surgery.”

Some of us fear surgery itself or the surgical process. Previous surgical experiences, good or bad, may influence how enthusiastic we are about “going under the knife” again.

“I have not had any gender-related surgery. I like my body as is, and I’ve had non-gender-related surgery and that experience was miserable. . .”

“I doubt I’d go through with it. . . if only because I have a strong aversion to having to see medical professionals for anything. Surgery is generally not something I’d want to go through ever again.”

Some of us fear potential surgical complications or do not think the results will be satisfying. For example, although we may desire a certain procedure, we may fear disappointment because of poor cosmetic outcomes, loss of sensation, loss of orgasmic ability, or urinary complications. We may want a newly contoured chest but fear scars. Some of us doubt that available surgical procedures will live up to our expectations for our imagined selves.

“I have thought about SRS for a long time, literally even before I identified as trans/genderqueer. But now that I know more about it, I really am not interested in going under the knife and risking my life for something that’s not going to work so well.”

“I was scared of surgery for the longest time, but I really wanted to be able to experience my sexuality the way it worked in my head. The results are still pending. It’s beginning to look like you’d expect, but things are still sore and there are still bits that are very red. Sensation is just beginning to return, but I don’t yet know how much sensation I’m going to have, or whether I can have an orgasm.”

As an alternative to surgery, some trans people use injection of free silicone or “pumping” to enhance their hips, buttocks, breasts, lips, cheekbones, and other body parts. The practice has gained increasing coverage in the news and has been a source of friction between some trans communities and the greater medical community due to the importance it holds for those who use it and the associated health risks the practice poses.

Why do some trans people use silicone injections? Cost is often the major determining factor in whether we are able to get the surgical procedures we need. Silicone injection may cost up to 90% less than traditional surgeries, making it more widely accessible. Many of us also prefer to avoid contact with medical providers due to previous negative experiences or fears of maltreatment.

What is silicone? Silicones are a family of chemical substances that are used for different purposes—from medical equipment and implants to industrial engineering. The specific makeup of different types of silicone varies based on what it is used for. Medical silicone, for example, is a much purer form of silicone than that used for other purposes.

How is silicone used medically? In medical contexts, silicone implants are enclosed in pouches designed to prevent the silicone from leaking out. Use of free silicone is not considered safe by the Food and Drug Administration outside of very specific eye surgeries. Certain medical providers—plastic surgeons and dermatologists—have developed “off-label” techniques (not approved by the FDA) in which free silicone injections are given in certain circumstances such as to counter the facial lipoatrophy (wasting) that sometimes happens in people with HIV. These procedures involve very small amounts of silicone—a couple of milliliters (less than half of a teaspoon)—injected into the face over multiple visits.

How are free silicone injections different than silicone implants? Injection of “free silicone” means that the silicone is not encased but instead injected directly into muscles and fat. This means it may move from the spot it is originally injected into or interact with the tissue surrounding it.

How are silicone injections different when performed outside of a medical context? Outside of a medical context, free silicone injections are often given in the quantity of liters (picture a 2-liter bottle of soda), which is up to a thousand times more than that used in medical contexts. Also, free silicone—unless specifically labeled as such—may not be medically graded, and it could be another form of silicone not designed for use in humans. It may therefore have additional toxic effects on the body or have substances other than silicone added to it.

Why are free silicone injections considered dangerous? There is consensus in the medical community that use of free silicone injections poses significant health risks. The degree of risk may increase based on the specific techniques and sanitation used for injection, the amount and quality of silicone injected, the site of placement, and the training of the person doing the injections. Many medical providers have seen their patients suffer greatly, or even die, because of infections, inflammation, necrosis (death to the tissue), or other serious and dangerous outcomes of having injected free silicone.

Examples of specific risks associated with silicone injections include the following:

• Migration. Free silicone injected at one spot may move through the body to end up in another, causing painful and disfiguring lumps. For example, silicone injected into the hips may end up behind the knees.

• Infections. These can occur at the site of the injections and can also spread throughout the body when they reach the bloodstream. Infections can cause damage and scarring at injection sites, and they can become life threatening when more widespread.

• Pulmonary embolism. Bits of silicone can migrate into the bloodstream (they are then known as emboli) and block blood vessels in the lungs. There, they can damage the lungs and cause a sudden and life-threatening condition.

• Damage to other organs. Bits of silicone can also become lodged in blood vessels leading to other organs, such as the brain, the heart, or the kidneys, and cause strokes, heart attacks, or kidney damage.

The potential dangerous effects of silicone can occur within minutes, weeks, or even years after injection. Because some of the harmful outcomes can happen very suddenly, it is important to know what to watch out for. Many symptoms that can result from silicone injection are not specific and could have another medical cause. However, any of the following symptoms after injection of silicone should prompt an immediate trip to the nearest emergency department:

• Shortness of breath

• Worsening warmth, redness, and swelling around the injection site

• Fever

• Dizziness

• A racing heartbeat

• Chest pain

• Nausea or vomiting

• Confusion

On arriving, it is critical to tell the health care providers there that silicone was injected so that they can provide the correct treatments. For example, the body’s immune response to silicone may appear the same as an infection but require a completely different treatment. It is also important not to delay seeking treatment or to withhold information for any period of time. The most serious complications from silicone injection are very time sensitive. The faster the proper treatment is applied, the better the chances for survival.

Aamina Morrison is a specialist and co-coordinator at the Trans-health Information Project (TIP).

Free-flowing silicone is a commonly known option for body modification among transgender women of color. With all of the crazy stories floating around about silicone usage, it is understandable that there are fears.

Many sites that are in support of professional cosmetic surgery procedures have demonized those who use silicone for a few decades now, magnifying the toxicity of its usage in free-flowing form, and characterizing individuals (especially transwomen of color) as lazy, poorly educated, and undesirable. With all of the horror stories and warnings that are given, we must examine the reasons why individuals, especially a community as disenfranchised and marginalized as the trans community of color, resort to these options for furthering their transition. It’s very simple: Money.

The economy only makes it harder for us to obtain employment, and even then we may not have medical coverage for basic primary care. When we factor in discrimination, societal exile, and the desperate need to further one’s transition at any cost, we have the formula for why our community is in such turmoil.

Imagine everyone—your peers, your friends, the media—recommending these professional options without trying to fix the far larger problems at hand. The blatant discrimination against trans individuals as a whole prevents sex reassignment surgery from being included in medical coverage, and the very old argument that the transgender experience is a disorder is still prevalent. Until these larger issues are addressed, silicone injections are not going anywhere.

It is important to make sure that our primary care providers know our history of silicone pumping for the same reasons that they should know our other surgical history. In addition, if we ever have complications at the sites where silicone was injected, any provider we see about this should be made aware. For example, if months or years later we get redness, warmth, and swelling over a site where we had silicone injected, this can look very much like a skin infection called cellulitis. However, it is more likely to be an immune reaction to the silicone. A provider who knows about our silicone use can provide us with the appropriate treatment, which may include a short course of steroid medications like prednisone instead of antibiotics, which will not help the problem.

Stories exist about people administering silicone as opportunists in order to exploit trans people. There are also many people who perform silicone injection and may be doing so as a service to friends or community members rather than as an attempt to exploit us.

It is important for trans people using free silicone and for medical providers to be able to have honest and open dialogue about this issue. Many of us have felt judged and ridiculed by our providers who tell us not to do it, and many medical providers feel frustrated by a practice they see harming their patients. More work needs to be done to bridge this gap in communication.

Going for surgery, gender related or not, can be a daunting process for anyone. For many trans people, fear of discrimination, the need to find highly specific surgeons, and the added steps necessary for approval can make the process especially difficult. The best way to embark on the journey of getting surgery is to first equip ourselves with knowledge about what to expect.

Doctors designated as appropriate to perform trans surgeries are trained in the fields of Plastic Surgery, General Surgery, Urologic Surgery, or Gynecologic Surgery, as specified by the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH). Generally, these surgeons are board certified, meaning they have passed additional examinations of competency within their respective specialty. However, most surgeons obtain their transgender surgical experience through a combination of specialization skills and apprenticeship with another surgeon or surgeons already performing these procedures. Specific fellowships in transgender surgery, done after residency, are not currently available in the United States.

Because of this lack of ability to credential surgeons, there have been cases in which surgeons without proper training in these procedures performed them, and this may remain a problem until a certifiable fellowship is established. Dr. Stanley Biber, who is considered by some to be the father of American gender-affirming surgery, performed his first surgery on a transgender woman in 1969 after adapting his surgical technique from drawings obtained from Johns Hopkins.

Choosing a surgeon requires consumer savvy in weighing personal needs, the intimacy needs of one’s partner, surgical offerings, and price and location of surgery, in combination with the surgeon’s reputation (person-to-person and online), potential complications and complication rates, functional and aesthetic surgical outcomes, recovery times, accessibility, waiting list, postsurgery care, and good old-fashioned “bedside manner.”

Here are some questions to consider:

• If you have a specific surgery in mind (and assuming you are eligible for that surgery), does your chosen surgeon perform and feel comfortable with that surgery? For example, you would prefer periareolar (keyhole) top surgery. Is your chosen surgeon comfortable with this surgery, and are you an appropriate anatomical candidate?

• Are aesthetic outcomes a top priority? Functional outcomes? Complication rates? What is the surgeon’s track record for results with the type of procedure you desire?

• Where is the surgeon located, and what would it mean to travel there? Is it important to be close for possible follow-up needs, or is there another local provider who could manage follow-up care? What about having surgery abroad?

• How much does the surgeon charge for a given procedure? There is no standardized list of costs for trans surgeries. This means prices may vary greatly from one surgeon to another, so it may be worth it to comparison shop a bit if this is a concern. What will be the other prices involved in the surgery (for example, anesthesiologist and hospital or surgical center payments)? If you have insurance, does the surgeon accept your insurance and will they help you preauthorize the care or do you have to pay in full and then appeal for reimbursement? What type of copay will you have?

• What type of reputation does the surgeon have for “bedside manner?” Some people are entirely focused on results, while for others the process plays a role in their decision making. Surgeons are people, too, and come with personalities of their own. If this matters, finding out more about others’ experiences might be important before getting rolling with your own. Many trans surgeons have patients that are willing to talk about their experiences, so it is worth it to ask the surgeon’s office for contacts or to look online for reviews.

As with many other resources for us, we may rely on personal referrals by friends and extended community networks as the first line of investigation. Being able to hear about the experience firsthand from someone we know will help prepare us for the process, and it may be an opportunity to see the results of a surgeon’s work firsthand. Many surgeons also have Web sites with pictures of their results.

Franco.

We can also ask trans-friendly medical providers or mental health providers for recommendations or referrals. LGBT-specialized medical clinics collectively see large numbers of trans people before and after surgery and may also refer us to a proper surgeon. Some have even assembled information packets, which explain surgical options and outline the surgical process. These providers see relatively high numbers of different surgeons’ results while providing follow-up medical care. They may have information on how satisfied patients were with their particular surgeons, and they may help us set realistic expectations. They are also likely familiar with the presurgical requirements for local surgeons.

TransBucket is an online resource for comparing and sharing surgical outcomes.

If traveling is a possibility, a number of conferences around the world offer gathering places for trans people, where there are sometimes surgery workshops. These include the True Spirit Conference, the Philadelphia Trans Health Conference, Seattle’s Gender Odyssey, California’s Transgender Leadership Summit, and Canada’s CPATH Conference, among others. There, we can meet other trans people, talk about the experience of getting surgery, and get information about trans surgeons. Some surgeons attend these conferences themselves and give presentations on their surgical techniques. Some conferences also have “show and tell” events for trans people considering surgery. Willing trans people who have previously undergone surgery show their results and talk about their experiences.

Before being approved for surgery, there are a number of steps we must go through to satisfy surgeons’ preoperative criteria. Some of the requirements are standard for most types of nonemergency surgeries, while others are specific to the particular surgeons and the surgeries they perform.

To start the process, most of us set up an initial consultation with a potential surgeon or surgeons. At this first visit, we have an opportunity to discuss our goals and ask questions. We may also get a feel for what it is like to interact with the surgeon and the surgical team. The surgeon may perform a physical exam and discuss different surgical options and what they believe are realistic surgical expectations. They should explain the different procedures in detail and inform us of possible risks and complications. If we have a specific surgical technique in mind, it is important to bring this up at the consultation and ask whether the surgeon feels comfortable with that technique in our case. Some surgeons provide free initial consultations, but most charge $100–$300 for the appointment.

Before the initial consultation, it is a good idea to think about and write down any questions. Whether we are excited, or nervous, or neither, the experience can be disorienting. Having questions ready can help make sure we get them all out there. For that reason and others, it is also a good idea to bring someone we trust with us to help gather and retain information. Here are some things to consider addressing:

• The different surgical techniques that particular surgeon has to offer

• The advantages, disadvantages, and limitations of each type of surgery

• Any before and after pictures available of prior patients

• The inherent and patient-specific risks of each surgical procedure

• Expectations about the appearance (scars, etc.) and function of that part of the body after surgery

Once we decide to pursue surgery with a particular surgeon, there are several other providers we may need to see first. The primary care provider who sees us prior to surgery helps us to determine whether we are physically healthy enough for surgery. A mental health provider may also be required to recommend us to have surgery. Many of us have strong feelings about the requirements imposed for hormones and surgery. Some of us as trans people are involved in organizations like WPATH so that we can be a part of helping to establish fair guidelines.

When we are seen by a primary care provider prior to surgery, the first step will be to examine us and assess our medical history and risk factors for undergoing surgery. This is sometimes referred to as “surgical clearance.” For young and healthy people, this may involve a single office visit and a few lab tests. If we have certain medical conditions or are older than 40, additional tests such as a chest X-ray or electrocardiogram (EKG) may be required. Infrequently, if we have significant medical problems such as heart disease, our primary care provider may require that we have a consultation with a specialist like a cardiologist before clearance can be given. If chest reconstruction is being performed, we may also need to have a mammogram done before surgery if we are older than a certain age or have a family history of breast cancer. All of this is standard for any planned surgery to make sure our bodies are healthy enough to undergo the stress of surgery and appropriately recover afterward.

Gatekeeping

Historically, the relationships between trans people and the medical and mental health fields have been rocky. Providers have often been perceived as playing the role of gatekeepers, holding us back from our ability to transition. For this reason, many of us have felt forced to convey a textbook story of having been born one gender trapped in the body of the other in order to satisfy providers and to secure the necessary approval for transition. Others have chosen to avoid medical and mental health care altogether. While this aversion may be understandable, it is important to recognize the potential benefits of working with trans-friendly providers, many of whom strive to be gate openers in helping us access care. No matter how we feel about our surgical decisions and process, it can be an emotionally tumultuous time, and having a skilled mental health professional on our support team can be invaluable. Likewise, medical providers can be valuable advocates and guides through the various medical processes. See Chapters 14 and 15 for more information on this topic.

Some preexisting medical conditions can make surgery more risky. For example, surgery may be more dangerous or have a greater risk of complications if we have heart or lung problems. Even something as simple as high blood pressure may put us at increased risk if it is not well controlled. Very rarely do a person’s medical conditions exclude them from surgery altogether. However, surgeons generally require that any serious health problems be well controlled before they operate. Many surgeons will also ask us to modify risk factors within our control, such as smoking, or temporarily discontinue specific medications that increase bleeding potential. Others may also require us to be within certain weight parameters to make surgery more successful.

Throughout the clearance process, it is extremely important to be completely honest with our surgeon and the other providers involved. To provide us with the best care possible, they need as much accurate and complete information as possible.

Along with surgical clearance, most surgeons will also require us to acquire one or two recommendations from mental health providers. Many surgeons rely on the WPATH Standards of Care (SOC), to identify patients for whom a specific surgery is appropriate. For chest/breast surgery, the SOC advise obtaining one letter of reference from a mental health professional confirming the presence of “persistent, well-documented gender dysphoria,” the “capacity to make a fully informed decision and consent for treatment,” legal adulthood, and if present, any significant mental health concerns be “reasonably well controlled.” For removal of the ovaries or testicles, the guidelines additionally suggest the above and two such letters, along with “12 months of hormone therapy appropriate for a person’s gender goals.” For vaginoplasty, metoidioplasty, or phalloplasty the above and “12 continuous months of living in a gender role that is congruent with their gender identity” are recommended. Some surgeons may follow a different set of guidelines or may have their own specific requirements in addition to those set out by WPATH.

In many cases we will need to see a therapist or psychologist to have an assessment and acquire a letter. However, the SOC also recognize that primary care physicians may have adequate expertise to assess patients, especially if they provide our care in a multidisciplinary environment (where medical and behavioral health providers work together to provide care in the same location). If our primary care provider has such competency and experience, generally their letter is sufficient for chest/breast surgery and as one of the two letters required for bottom surgery.

Cost is often the biggest logistical barrier between trans people and surgery. In the United States, the majority of gender-affirming surgeries are paid for out of pocket by patients. However, this is changing. Recently, California, Oregon, Vermont, and the District of Columbia have started enforcing law and policy that insurers cannot exclude transgender health care services from insurance policies. In addition, an increasing number of corporations, universities, local governments, and large unions like CalPERS in California are providing health insurance that covers transgender medical and surgical treatments.

Despite these promising advances, for most of us, the amount of money needed for surgery is not easily accessible, and for many of us it takes years to raise the funds, if we are ever able to do so. There are a number of different ways we may pay for surgery.

Some surgeons work with lenders to provide payment plans. If paying little by little is a possibility, this might be an option to at least expedite the actual surgery. Different surgeons work differently in this regard, but if it is an appealing alternative, it is worth asking.

Despite the fact that many insurance companies specifically exclude coverage of transgender surgeries, and that trans people are less likely to have employer-sponsored or privately purchased health insurance, in an increasing number of instances, insurance may be useful to cover gender-related surgeries.

A growing number of employers and schools have independently negotiated for coverage of transgender care in their plans. If you are thinking about going to or working for a college, this might be something to consider when applying. A list of universities with trans-inclusive insurance plans can be found on the Web site for the TONI (Transgender On-Campus Non-Discrimination Information) Project.

Having an anatomically related health issue that is not considered connected to our trans status may open the door for insurance to pay for the surgery. For example, if you would like breast tissue removed, a family history of breast cancer might make insurance funding possible.

“I had medical insurance when I had chest surgery and was able to get it covered as a breast reduction. My insurance company was not aware that it was a transgender related surgery, otherwise, they would not have covered it.”

One potentially major drawback of dealing with insurance companies is that they may obligate us to go to a specific surgeon within their network of providers. If we have our heart set on a particular surgeon, it might not be possible through insurance coverage. However, we may be able to argue that there is no one in-network with the appropriate skills and experience.

Another strategy many of us utilize to help afford surgery is to call on family, friends, and community members for support by requesting individual donations or holding fundraisers. Different people organize these events differently based on personal taste, talents, and community, but some example ideas include the following:

• Benefit events: dance parties, concerts, comedy nights, dinner parties with an entrance fee, paid food or drinks, or a donation bucket

• Donations via the Internet: donation sites with a written request posted on a private Web site or circulated via social media

A relatively new resource for funding transition-related surgeries is the Jim Collins Foundation, a unique nonprofit organization that has the explicit mission of providing financial assistance to transgender people for gender-affirming surgeries. The organization accepts applications between April 1 and August 1, and the number of grantees varies per year based on the success of fundraising efforts. Their grantees are selected based on financial need and level of preparedness, according to their Web site. Visit their Web site for more information on the application process or to make a contribution to the organization.

Many of us have to travel to another town or city for surgery. Before setting off, it is a good idea to make sure all necessary logistical arrangements are taken care of. These may include travel plans (flights, trains, someone to drive us, etc.), staying arrangements (depending on the surgery and our general level of health, this may require staying overnight one or more nights in a hospital), and who will be accompanying us. Some surgeons have developed relationships with nearby hotels, which may provide deals for medically based stays or assistance with transportation to and from the surgical site. They will provide this information at the time of the initial consultation, but if it is important to know beforehand, it is worth asking when you call. If you need to stay around for follow-up care, make sure you know in advance how long this is likely to be.

There are numerous surgical options that have the potential to alter our gendered appearances. We may have “top” surgery to increase the size of our breasts (breast augmentation) or to create a more male-contoured chest. “Bottom” surgeries refer to procedures performed on our genitals or reproductive organs. There are also a number of other surgeries that can be performed to change our gendered appearance, such as facial or tracheal surgeries.

There is no one-size-fits-all approach. Each of us must identify our own particular goals. We may ask ourselves which, if any, body parts feel inconsistent with our gender identity or cause us distress. We may consider which situations (public spaces, intimate partnerships, looking in the mirror) cause us to feel these discrepancies most acutely. We may also think about what would help alleviate our distress—being able to urinate while standing up, seeing a different reflection in the mirror, being more physically comfortable by not having to tuck or bind anymore, or requiring a lower dose of hormones.

The information in this chapter has been compiled to give a general overview of the types of surgical procedures that many of us choose from. Before choosing a surgery, it is very important to fully understand the specific risks and complications associated with it—every surgery will have the possibility of complications and some of them can be serious. The list of possible complications in this section is not comprehensive or complete, and it should not replace a detailed conversation with the surgeon performing the procedure(s).

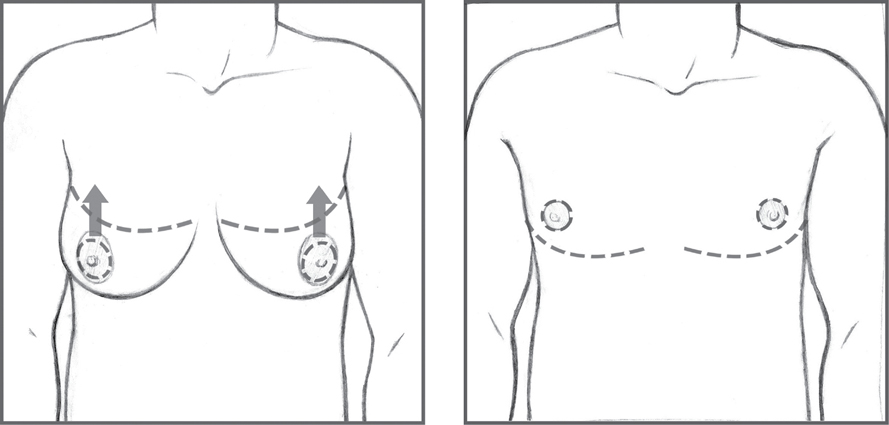

Top surgery refers to surgeries performed on our chests. These include breast augmentation, as well as reconstructive chest surgery to create a male-contoured chest. Top surgery is more common than bottom surgery for those of us on the transmasculine spectrum because it costs less and has a greater impact on our outward appearance.

Reconstructive chest surgery, commonly referred to as “top surgery,” involves removal of breast tissue and formation of a male-contoured chest.

$5, 000–$10, 000

There are a number of different techniques for reconstructive chest surgery, with the two most common types being double-incision procedures and periareolar (keyhole) procedures. The type of surgery we get depends both on our preferences and the recommendation of the surgeon, who will suggest a particular procedure based on the size, shape, and skin elasticity of our original chests. Each surgeon has particular standards for size and elasticity that guide which surgery they feel most comfortable with for a given patient.

In this procedure, incisions are made at the base of each breast, and breast tissue and excess skin are removed. The nipples and areola are taken off, resized, and grafted back into the appropriate position. This procedure can be used with any chest size and shape, but it is often reserved for those with larger chests or minimal elasticity. The procedure leaves sizeable scars on both sides of the chest.

Because the nipple and areola are removed and replaced, there will be loss of erotic sensation to the nipple, though generally nonerotic sensation will return but may take months to years. In some cases, the nipple and areola are completely removed and a subsequent surgery or tattooing is performed to re-create the appearance of nipples. This may be necessary if you are a carrier of gene mutations that increase your risk for breast cancer.

Double-incision (Ron Burton).

In this method, incisions are made around the borders between the areolas and the surrounding skin, and breast tissue is removed through these incisions. Some skin may be removed, and the remaining skin is reattached at the border of the areola, which leaves minimal scarring. This procedure is typically reserved for smaller chest sizes or a smaller amount of loose skin, and is associated with faster healing times. Usually, erotic sensation of the nipples is preserved with this procedure.

Keyhole incision (Ron Burton).

A minority of patients with very small presurgical chest sizes may choose to have liposuction only. Erotic sensation is usually preserved, but since the breast tissue remains there is a greater risk for breast cancer and need for screening. In addition, if you have this procedure and later become pregnant, there is a good chance that the breast tissue will become more prominent again during pregnancy.

Reconstructive chest surgeries are generally performed without an overnight stay in the hospital. However, it may be necessary to stay locally for a period of time. Drains—pieces of long thin tubing with plastic bulbs on the end—are typically placed under the armpits to allow fluid to leave the body, and are removed a few days to a week after surgery. Time for return to regularly scheduled (nonstrenuous) activities varies by surgical type and the individual, but upper body weight bearing is typically not advised for six weeks.

After the procedure, it is common for some people to feel numbness in the chest and nipples. Some people also experience tingling, burning, or other sensations. For many, these feelings resolve and normal sensation returns over a period of months to a year as inflammation decreases and nerves regrow. However, many also experience some permanent loss of sensation.

It is also important to note that some breast tissue will remain with any technique, so we should make sure to discuss routine screening for breast cancer with our primary care provider. This usually involves a simple chest exam in the office.

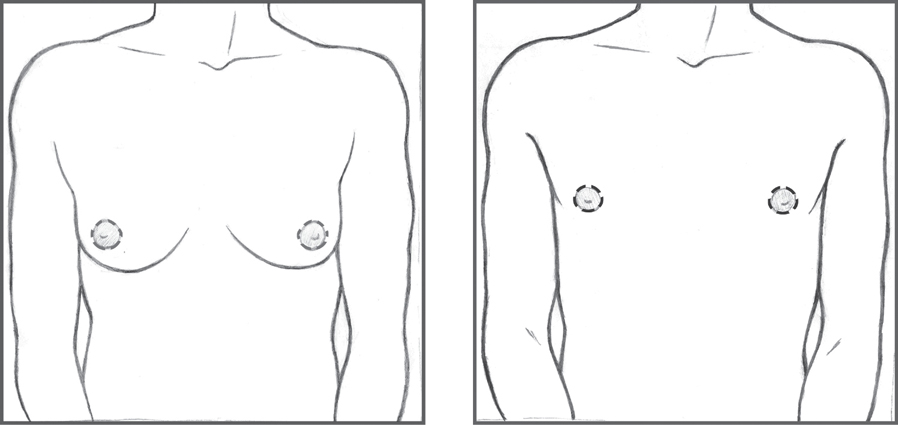

Breast augmentation involves increasing the size of the breasts. It is a common procedure in cisgender women.

$6, 000–$8, 000

In breast augmentation, implants made of either enclosed silicone or saline are used to enhance the size of the breasts. Incisions are made around the areola (circumareolar), near the armpit (axillary), or just below the breast (inframammary). The implants are introduced through the incision and situated either in front of or behind the pectoral muscles. Other alternative methods involve the transplant of fat, muscles, or tissue from other parts of the body into the breast.

It is important to note that use of estrogen will stimulate breast growth. Many people are satisfied with hormonally induced growth alone. While it is not a criterion for referral for surgery, the WPATH Standards of Care recommend that at least 12 months of continuous hormone treatment is done before surgery to see the outcome of natural breast growth. Some surgeons even recommend this be as long as 18 months.

Breast augmentation is often done in an outpatient setting (i.e., not in a hospital), and it may not require an overnight hospital stay. However, we may need someone to accompany us after the surgery, and the surgeon may require us to stay locally for an additional few days.

Maddie Deutsch, MD

Different breast augmentation techniques require different aftercare. Silicone implants can leak or rupture, or a capsule of scar tissue called a capsular contracture can form around them. Silicone implants that are leaking may cause no symptoms, or they may cause lumps, pain, or a firm or immobile implant. Silicone leaking out of an implant may travel to places near and far in the body, and cause pain, lumps, and inflammation. Research shows that by 10 years, most silicone implants have leaked to some extent.

Once a silicone implant has leaked, there are a few approaches to take. If there is no pain, we may simply do nothing. If the implant is firm or painful, the surgeon may suggest removing or replacing the implants. Each time an implant is replaced (including to gain a larger size), there is an increased risk of scarring or contractures, as well as infection. If the implant becomes infected or is scarred to the point that it cannot be replaced, it might leave breasts that appear saggy.

Saline implants also run the risk of contracture or infection, but the risk is less than with silicone. Since saline implants are filled with salt water, when they leak, they leak quickly. A sudden and rapid loss of breast fullness and shape will result—this will be quite obvious. The salt water is absorbed into the body without any harmful effects.

Bottom surgeries are those procedures performed to alter our genitals or internal reproductive organs. These surgeries are generally among the most expensive of surgical options, often costing upward of $30, 000 or more. Many of us delay or do not have bottom surgery due to the prohibitive cost, or because we choose to prioritize more publically visible aspects of appearance. Some of us also experience pleasure from our genitals and do not wish to chance compromising function or satisfaction. Others wish to maintain fertility. For those of us who do prioritize bottom surgeries, however, they can be deeply meaningful and provide a profound sense of relief.

“I had a vaginoplasty, which I decided to have as soon as I realized that I was a transsexual. . . Due to poverty and cultural disapproval, I had to wait over nine years for the procedure. When I awoke from surgery, I looked out my clinic bedroom window. . . At last I felt like me.”

$3, 000–$5, 000.

An orchiectomy is the removal of the testicles. The testicles produce sperm, as well as the hormone testosterone, so an orchiectomy may eliminate the need for testosterone blockers, such as spironolactone, and reduce the amount of estrogen required to achieve and maintain the desired effects. The procedure can be done under local anesthetic or general anesthesia, and it is generally far less expensive than vaginoplasty—the creation of a vagina. Rarely, scarring from the procedure can affect the results of a vaginoplasty in the future. Most surgeons do not have a problem with this, but we should consider talking with our surgeon about whether this might impact future surgical options.

Orchiectomies are typically done on an outpatient basis, which means we do not have to stay in the hospital overnight. Most surgeons, however, will require that we have someone to accompany us out after the procedure, and some require that we stay locally for up to three to five days. After this time, we should be able to return to regularly scheduled activities, if they are not too strenuous, and be back to most activities within two weeks.

Once the testicles are removed, we may be able to stop testosterone blockers, but it is important to stay on some form of estrogen so our bodies have hormones to keep our bones and other parts of our bodies healthy. Removal of the testicles will result in complete and permanent inability to have biological children. If children may be desired in the future, we should consider preservation of sperm.

A penectomy is the removal of the penis with or without reconstructive efforts. In the United States, penectomies are rarely performed, having been mostly replaced by vaginoplasties.

$15, 000–$30, 000

Vaginoplasty is the creation of a vagina. Tissue from the shaft of the penis is used to construct a vaginal canal. The glans (head) of the penis and the nerves that supply it are used to create a clitoris (clitoroplasty) and scrotal tissue is used to create the labia (labiaplasty). Alternative techniques may involve taking skin from another area of the body or tissue from the colon to create the vagina, although this is less commonly used and often leads to more complications, such as constant discharge. A labiaplasty to improve the aesthetics of the labia and to create a clitoral hood may also be performed in a second surgery, although today most vaginoplasties include labiaplasties.

Generally, overnight stays in the hospital are necessary after vaginoplasty. When first out of the surgery, we will have a catheter, a long thin plastic tube, coming out of the urethra, which we will urinate through. This is usually removed one to two days after surgery. We may not be able to safely travel home for a week or more.

Electrolysis or laser hair removal of the penile and scrotal areas is generally recommended before vaginoplasty to provide hair-free tissue for the procedure. This process may take several months. Surgeons have different opinions about presurgical hair removal, so it is a good idea to gather as much information as possible from your surgeon well in advance of the surgical date.

The prostate is not removed at the time of vaginoplasty. This is because removal of the prostate is not needed to get good results and removal risks greater complications, including blood loss, infection, and loss of control over urinary function.

SRS results (Pichet Rodchareon, MD).

Recovery time can range from one to two months. It is important to follow the surgeon’s instructions carefully as per the length of time to wait before engaging in sexual activity with the new vagina. The surgeon will also provide a set of vaginal dilators, used to maintain, lengthen, and stretch the size of the vagina. Dilators of increasing size are regularly inserted into the vagina at time intervals according to the surgeon’s instructions. Dilation is required less often over time, but it may be recommended indefinitely.

Complications of vaginoplasty can include infection, fistula (a small tunnel that develops between the rectum and the vagina), and slow healing (also called granulation tissue) that can be painful or bleed. Although the procedure also comes with a degree of risk in terms of loss of sensation or interference with urinary function, long-term outcomes for sensation, orgasmic ability, sexual satisfaction, and urinary function are much improved. Despite possible complications, various studies have shown that after vaginoplasty, there is an improvement in our quality of life, body satisfaction, and psychosocial function. The WPATH Standards of Care Version 7 includes an appendix, which discusses all of the studies we have so far about the outcomes of surgeries, including vaginoplasty.

In metoidioplasty, the clitoris/phallus length is increased without grafting tissue from other parts of the body.

Depending on the type of procedure and the surgeon, metoidioplasties may cost less than $5, 000 without, and more than $15, 000 with urethral lengthening.

During this procedure, the clitoris/phallus is freed from its attachments to the labia minora and a suspensory ligament (which holds the clitoris/phallus close to the body). The overall effect is to lengthen and straighten the clitoris/phallus. Greater girth is also achieved by bringing the undersurface of the clitoris/phallus and added bulk from the labia to the midline. An additional procedure known as a “urethral hookup” can be done at the same time, which allows for standing urination. In a urethral hookup, the urethra is extended through the released clitoris/phallus using a graft traditionally taken from the lining of the mouth. A newer variation of the metoidioplasty called the ring metoidioplasty is performed with a urethral hookup consisting of lining derived from the inner labial skin and a flap from the vagina, eliminating the need to take tissue from the mouth.

Metoidioplasty typically results in an unstimulated phallic length of between 3 and 8 cm. Full sensation and erectile and orgasmic functions are generally retained. The procedure may also be converted to a phalloplasty—creation of a penis—at a later time if desired.

Many people take testosterone to enlarge the clitoris/phallus prior to metoidioplasty. Some surgeons recommend the use of topical testosterone creams or pumping, although there is no research yet as to whether these techniques increase phallic size. If we do use pumping, it is important to avoid anything that causes pain or numbness. Pain and numbness can signal tissue damage, which could ultimately make our surgical results worse.

Surgery to permanently close or (less often) remove the vagina is not required for a metoidioplasty. Penetration and Pap smears may not be possible following a metoidioplasty. Some surgeons recommend removing the uterus, cervix, and ovaries at the same time as the metoidioplasty, while others do not. Scrotoplasties (creation of scrotum) are also sometimes done along with metoidioplasties.

Depending on the type of metoidioplasty, when we first come out of the surgery, we may have to remain in the hospital for a short time and may have a catheter, a long thin plastic tube, coming out of the urethra, which we will urinate through. This is usually removed 1–2 days after surgery. Recovery time for metoidioplasties may be up to two weeks, and may require remaining close to the surgeon for at least a few days.

For more information on bottom surgeries for trans men, check out Trystan Theosophus Cotton’s book Hung Juries: Testimonies of Genital Surgery by Transsexual Men (Oakland, CA: Transgress Press, 2012).

Phalloplasty is the creation of a penis. Phalloplasties are relatively rare in the United States due to high cost, the need for multiple procedures, scarring at skin donation sites, and variable results.

$30, 000–$100, 000

Donor skin with which to construct the new penis is taken from another area of the body, typically the forearm, lateral thigh, calf, lower abdomen, or flank. The skin is then rolled into the shape of a phallus, and is anchored in the normal position for the penis. Phalloplasties require a large amount of donor skin, and the graft sites often heal with significant scarring or disfigurement. Most surgeons situate the clitoris/phallus within the base of the new phallus in an attempt to retain erogenous stimulation. Generally, this is at least somewhat successful but it is possible to permanently lose erotic sensation.

The procedure is often broken up into multiple steps, with up to three scheduled surgeries. Urethral lengthening to allow for urination through the tip of the penis is considered a difficult addition to the procedure, but can be done. Variations may also include grafting of nerves and blood vessels to provide sensation to the new penis, however this is considered a much more complex procedure, with a higher likelihood of complication and is not frequently done. A glansoplasty may also be performed as a separate procedure to sculpt the head of penis. Medical tattooing may also be used to create a distinction between the head and shaft.

Silicone rods or pumps are sometimes inserted into the penis to allow it to become erect. These rods or pumps may allow for desired sexual practices, but may be uncomfortable, and there have been reports of them becoming infected or eroding through the skin.

When emerging from surgery, there will be a catheter, a long thin plastic tube, coming out of the urethra, to urinate through. Depending on the type of surgery, it may take some time for this to be removed. After phalloplasty, we will have to stay in the hospital for at least a few days. Phalloplasties have relatively high rates of postoperative complications and may require multiple follow-up surgeries. Recovery rate is largely variable, from about four to twelve weeks depending on the individual and the exact procedure.

A scrotoplasty is the creation of a scrotum. In a scrotoplasty, testicular implants are inserted into the labia, which are sealed around them.

$3, 000–$5, 000

In this procedure, egg-shaped silicone implants are placed into the labia majora through small incisions. In preparation for permanent prostheses, expanders may be placed under the skin to encourage the expansion or growth of new skin. This is done by gradually filling the expanders with more saline through an external port over a period of months. Once the skin is adequately expanded, the permanent implants are inserted.

Each expansion procedure is generally performed in an outpatient visit, and so does not require an overnight stay at a hospital. The surgeon will likely require a local stay for a few days, and because the expansion procedure is gradual, it is necessary to return several times before placement of the permanent prosthesis. A common complaint is that the implants are uncomfortable. Less frequently, they have the potential to wear through the surrounding tissue or to become infected.

Hysterectomy is removal of the uterus, and may or may not include the cervix and upper part of the vagina. If one of the surgical goals is to eliminate the need for ongoing Pap smears, it may be best to ask the surgeon to remove the cervix as well. A hysterosalpingo-oophorectomy (HSO) includes removal of the uterus, fallopian tubes, and ovaries.

The procedure typically costs between $6, 000 and $8, 000, but it may be less if combined with other procedures. Hysterectomy/HSO is also covered by insurance more frequently than many of the other described surgeries because it can often be argued that it could help with non-gender-related issues such as menstrual pain.

There are several methods for performing a hysterectomy:

1. Laparoscopic (robot-assisted) approach. Small incisions are made in the abdomen through which a tiny camera and specially designed surgical tools are inserted to perform the procedure. Unless there are specific reasons to do otherwise, a laparoscopic approach is generally preferred due to minimized scarring and shortened healing times. Recovery time for this type of procedure is typically one to two weeks before return to daily function, and no more than a two-day hospital stay.

2. Vaginal approach. This procedure is similar to that described above, but entry is through the vagina rather than abdominal incisions.

3. Open (abdominal) approach. In this procedure, a larger incision is made in the lower abdomen above the pubic bones through which the uterus and ovaries are removed, usually resulting in a larger scar. Recovery time is typically longer for this procedure and can be up to six weeks. Generally, this is done when the uterus or ovaries are too large to be removed through the small incisions with laparoscopy. Recovery time is typically longer for this procedure and can take up to six weeks before complete healing is achieved.

When making a decision about whether to have an HSO, we may want to consider whether testosterone changes the risk of gynecologic cancers (cervical, ovarian, or endometrial). As a baseline, we should assume our risk is at least that of a cis woman. Removal of the ovaries significantly reduces that risk. There is not enough information in the medical literature to give any reliable advice on whether ovarian cancer risk is increased, decreased, or unchanged when taking testosterone. The risk of cervical cancer appears to be no different from that of cis women as long as we follow recommended screening tests. There is debate about whether the risk of endometrial (uterine) cancer is higher. If we get appropriate screening tests and make sure to report any abnormal bleeding to our providers, most uterine cancer, if it develops, will be found early enough to treat.

Overall, there is a need for more research in this area to arrive at a more definitive answer for these questions. Currently there are no guidelines to suggest that HSO is necessary at any specific point after beginning testosterone, but some of us choose to have this surgery. It is reasonable to consider a reduction in the risk of cancer and need for fewer screening tests as one of the benefits we weigh when deciding to have surgery.

Gender-related head and neck procedures include facial feminization surgery (FFS), tracheal shave, and hair transplantation. Some of us find that these procedures have been crucial in our transition, often above all others, because they impact those parts most readily seen by others.

Many surgeries not performed on the chest or genitals are referred to as cosmetic. It is important to distinguish between cosmetic and elective. Cosmetic surgery includes procedures done to alter the physical appearance. Elective generally means that the surgery is not necessary to treat a health problem. There are cosmetic surgeries that are elective, such as a face lift to appear more youthful. However, not all cosmetic surgeries are elective. For example, if a child has burns to the face with noticeable scarring, he might have medically necessary cosmetic surgery. Trans women often undergo medically necessary cosmetic surgeries to the face in order to feminize their features. Gender-affirming surgeries, including facial feminization surgeries, are medically necessary cosmetic procedures whose benefits include improved ability to be read consistently as female, as well as to avoid harassment and discrimination.

“Man, I hate it when people refer to procedures like electrolysis or Adam’s apple reduction surgery as cosmetic. For some people, they’re a necessary step toward alleviating gender dysphoria. The medical community shouldn’t be able to decide when individual trans people should be ‘finished’ or satisfied with their transition. Moreover, for some people such ‘cosmetic’ procedures as electrolysis or Adam’s apple reduction surgery are a matter of safety. If you don’t pass completely successfully 100% of the time in society, you may be physically or sexually assaulted or killed. There’s nothing ‘cosmetic’ about that.”

“I consider Facial feminization surgery one of my highest priorities alongside getting my voice right. . . People don’t look at your genitals. Your voice and your face are how people judge you in face-to-face conversation and are what you look at every day in a mirror.”

FFS represents a diverse set of plastic surgery techniques in which alterations are made to the jaw, chin, cheeks, forehead, nose, and areas surrounding the eyes, ears, or lips to create a more feminine facial appearance. The hairline may be adjusted to create a smaller forehead, cheekbones and lips can be augmented to become more prominent, and the jaw and chin can be reshaped and resized to resemble more classic feminine facial features. In the process, significant amounts of bone may be reduced, or prosthetic implants may be inserted. Reduction in bone mass may potentially lead to excess skin, and some people choose to have additional skin tightening surgeries as well.

Cost can vary greatly depending on the number of procedures desired.

The techniques used in FFS can be highly varied between different surgeons, and it is a good idea to understand those employed by a potential surgeon, as different techniques come with different risks.

Most facial feminization surgeries are performed on an outpatient basis, with no hospital stay required. However, complete recovery time may vary depending on the number of FFS procedures combined. Most procedures require about 2 weeks recovery time, but adjustments to the jaw may result in significantly longer recovery.

This procedure minimizes the thyroid cartilage (also known as Adam’s apple), a traditionally gendered feature.

$3, 000–$5, 000

In a tracheal shave, a 3–4 cm incision is made under the chin, in the shadow of the neck, or in an existing skin fold, to conceal the resulting scar. The cartilage is then reduced and reshaped. The surgery is sometimes performed at the same time as others elsewhere on the body.

Tracheal shave is generally performed in an outpatient setting, which means it will likely not require an overnight stay. However, there is usually a requirement to have someone to accompany us when we leave.

In this procedure, hair follicles from the back and side of the head are removed and transplanted to balding areas of the head. Costs vary greatly based on surgeon and size of scalp to be grafted, but they generally range from $4, 000 to $15, 000.

Postoperative care greatly depends on the type of surgery we have. Recovery time may be anywhere from a few days to over a month. Planning ahead can help us to make sure we have everything we need during our recovery period.

One thing we should find out before surgery is what the expected length of recovery time will be for our surgery so that we can make accommodations to give ourselves adequate time off from any activities that might slow down the healing process. Numerous people have shared experiences of pushing their recovery time by going back to work too soon, exercising to build up their newly contoured (yet unhealed) chest, or prematurely using their new sexual equipment. Time off, particularly from work, will be more challenging for some people than others based on financial resources. However, it is important to keep in mind that complications in the healing process may compromise our long-term outcomes and, depending on the complication, may require additional surgery or lengthen our overall healing process even further.

Having a well-planned support team in place to welcome us home can make the healing process smoother, both physically and emotionally. We may require assistance with some of our basic daily activities, such as cooking, bathing (we may not be able to shower for up to a period of weeks), using the bathroom, getting around, and performing basic household tasks. Our support people should include whoever makes most sense for us—friends, family, partners, community members—and ideally people who we would feel comfortable having help from in vulnerable situations (i.e., using the bathroom, sponge baths, etc.). Some people choose to preplan caretaking shifts to ensure that help is always available and that primary caretakers have added support as well. Support people can also provide us with the invaluable resources of love and affirmation, which are just as critical in the healing process.

Before surgery, some people choose to “surgery proof” their living space. Depending on the type of surgery we plan to have, we may have limited mobility or range of motion of particular body parts for a period of time. For example, after top surgery, lifting the arms up overhead or bearing weight with them may not be possible. Placing necessary items at a level easily reachable for our postsurgery selves may increase our independence and physical comfort. Many people also choose to invest in or borrow pillows to prop themselves up while resting. Something else to consider is how we might occupy our time while letting our body recuperate. We may or may not have a lot of mental capacity in the days after surgery, so movies, easy reading material, and good company are good investments.

After surgery is complete, and we have been cleared by the surgeon to go home, we will require follow-up medical care. The particular surgeries, surgeon, and any complications that arise will determine the specifics of this care. If our surgeon happens to be within reasonable travel distance, they may be the one to continue caring for us. For many people, however, their surgeons of choice are in another state or country, and accommodations must be made to have access to another provider. If we had not previously found a trans-friendly and knowledgeable medical provider prior to surgery, it is imperative that we find someone who can monitor our progress and help distinguish between a normal healing process and complications.

We may also require follow-up procedures. For example, some surgeries require the placement of drains to collect blood and other fluid that our body naturally produces as a response to the trauma of surgery. Excess fluid collections can cause hematomas (collections of blood) and seromas (collections of plasma without the presence of blood cells). A portion of the drain is placed inside the body, which connects to collecting bulbs outside the body that are secured with stitches. The drains will remain in place until a time specified by the surgeon and then must be removed by a medical professional. It is a good idea to know before surgery who will be removing the drains. Leaving them in for too long can open the door to additional complications, and medical providers unfamiliar with the procedure or surgeon may hesitate to touch the work of a surgeon unfamiliar to them.

To receive the best follow-up care possible, it is also beneficial to be informed about the type of surgical procedure we had. The more information we can provide, the more our medical providers will know what kind of care we require. We may even choose to bring copies of our medical records to show new medical providers.

Knowing the details of our surgery will also ensure that we get the best preventive medical care, even after we have healed. For example, after a vaginoplasty, we likely still have a prostate and will need appropriate cancer screening. Or, if we have had our uterus removed, it is important to know whether we still have a cervix, which may also require proper cancer screenings with Pap smears.

In addition to finding a competent local medical provider to oversee our follow-up care, we should not hesitate to contact our surgeon if we have any questions at all regarding the recovery process. Ideally, the surgeon and their staff should be available for questions. Because they were the ones who performed our surgeries (and likely hundreds or even thousands like them before), they will be most familiar with what was done and with any potential complications.

Before leaving the surgeon’s office after surgery, we should also be given a written set of postsurgical instructions. This might include a timeline for removal of bandages or drains, when we may start activities again, how to use our dilators (if applicable), possible complications, and signs/symptoms that should prompt us to seek medical attention. It is important to read, completely understand, and follow these instructions. It is the surgeon’s responsibility to make sure we have all the information we need for as successful a recovery as possible, and it is our job to ask for clarification if we need it.

In addition to following up with an appropriate medical provider, it is a good idea to keep ourselves as healthy as possible throughout the healing process to boost our body’s natural ability to repair itself. This means getting enough sleep, staying well hydrated, and having the proper nutritional intake. Healing after any type of surgery requires additional energy and nutrients. In particular, adequate protein, vitamin A, vitamin C, B vitamins, and zinc are known to be important in healing. It is also important to refrain from activities that will actively slow down healing, such as smoking cigarettes.

Some people also choose to use “complementary” health modalities to assist in the healing process, such as acupuncture. Massage therapy has also been shown to decrease inflammatory chemicals in the body, and it has been used successfully to improve the appearance and functional movement of scar tissue. Consult your surgeon about when in the healing process it is appropriate to utilize massage or other modalities involving direct contact with the postsurgical areas of the body.

Billy J. L. Scott, LAc, Dipl. OM (NCCAOM), is an acupuncturist working in both Philadelphia and Austin, with a focus on providing affordable, quality care in the LGBT community.

Acupuncture is the insertion of thin solid needles into energetic points in one’s body, in order to treat illnesses and restore balance. Postsurgical acupuncture can reduce healing time and benefit cosmetic results, particularly in combination with pharmaceutical and/or herbal medicine. It has been shown to relieve inflammation, promote circulation, decrease pain and swelling, and reduce scarring. In addition, it can address other issues that may be exacerbated by surgery, such as sleep disturbances, digestive issues, and anxiety and depression.

The setting and style of acupuncture you receive can vary from clinic to clinic. In general, a private acupuncture setting involves receiving treatment in your own room. These treatments can provide more privacy and one-on-one time with the practitioner. Community acupuncture involves receiving treatment in a room with others. These treatments are more affordable than private acupuncture, which can allow for more frequent treatments and possibly faster results. Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), Japanese style, Tan/Tong’s balance method, and Five Element are just a few of the styles of acupuncture. The differences between these styles may be difficult to discern, and most acupuncturists use a hybrid of styles and techniques. Each style can achieve beneficial results when performed by a skilled practitioner.

You can locate an acupuncturist in your area by visiting the Web site for the National Certification Commission for Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine. Community acupuncture clinics can be found through the People’s Organization of Community Acupuncture.