In This Chapter

Exploring what psychosis means

Exploring what psychosis means

Defusing from psychotic thoughts

Defusing from psychotic thoughts

Discovering how to accept the symptoms

Discovering how to accept the symptoms

Imagine thinking that people in your street are spying on you and telling the police about everything you do. When you meet them they take notes and pass them to the authorities. You don’t understand why they’re behaving in this way because you don’t think you’re doing anything wrong. It feels like everyone’s out to get you. Alternatively, you may hear voices in your head telling you to do things or saying nasty stuff about you or other people. No matter what you do, those voices are always with you, relentlessly dominating your thoughts.

If these things were happening to you, you’d probably find the world a scary and difficult place. These types of experience are the basis of psychosis and they can make the world seem very dark and disorientating indeed.

This chapter outlines the experience of psychosis from an Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) perspective and describes what can be done to support people struggling with it.

While we do present some proactive ideas and options, these shouldn’t be seen as an actual intervention programme for someone experiencing psychosis. If you need to access such a programme, seek advice from your GP.

While we do present some proactive ideas and options, these shouldn’t be seen as an actual intervention programme for someone experiencing psychosis. If you need to access such a programme, seek advice from your GP.

Understanding Psychosis

Psychosis describes a condition involving three related experiences:

Psychosis describes a condition involving three related experiences:

- Delusions: You believe something to be true when it’s actually false or highly unlikely. For example, believing your neighbour is conspiring to hurt you or MI5 is monitoring your phone calls.

- Hallucinations: You see or hear things that aren’t there. For example, seeing fairies at the bottom of the garden or hearing Napoleon talking to you.

- General confused and disturbed thinking: You’re unable to function because your thoughts are so jumbled up that nothing makes sense. These symptoms mean that psychosis can be a very frightening experience. You may feel very threatened when you’re experiencing psychosis, which can make you behave in bizarre and even dangerous ways.

Seek immediate specialist help if you or someone you know experiences these symptoms.

Seek immediate specialist help if you or someone you know experiences these symptoms.

The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) estimates that 1 per cent of the adult population will experience psychosis at some point in their lifetime. This may appear a small percentage, but it represents a great many people in distress. For approximately 20 per cent of people it will be a one-off event, a moment of crisis that they recover from. For others, psychosis can become a recurring pattern in their life. Evidence shows that specialist support after the first episode reduces the likelihood of future re-occurrence. To support these efforts, NICE has issued best practice guidance on how to respond to first- and multiple-episode psychosis (see clinical guideline 178 at www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg178 for advice).

Psychosis is a complex condition and the specific processes and mechanisms that underpin it are still mostly unknown. That said, two broad sets of circumstances are associated with an initial psychotic episode:

- Illnesses and health conditions: People can experience psychosis as a result of a stroke, a brain tumour, dementia or nutritional deficiencies, for example. Postpartum psychosis can also occur in women after childbirth.

- Environmental factors: Drug and alcohol use is a common precursor to psychosis. In addition, psychosis can occur after a traumatic event, such as a physical assault or the death of a loved one.

In many ways, the ACT model is well-matched to the challenge of psychosis. People with psychosis typically experience disturbing thoughts and feelings that can impair their functioning and everyday living. And ACT specifically targets disturbing thoughts and feelings to facilitate more meaningful and positive lifestyles. ACT works on the specific mental distress that people with psychosis experience by helping them develop psychological flexibility (Chapter 3 gives you all the details).

Psychological flexibility means being open to and accepting of unwanted negative internal events (such as thoughts, feelings and sensations) while continuing to engage in behaviour that reflects your values (that is, how you want to behave in life, such as being a kind person or raising your children with respect and compassion). When you’re more psychologically flexible, you’re more connected with the world and more able to do the things that matter to you. And this seems to be the key problem for people with psychosis — their troubling negative thoughts and emotions overwhelm them to such an extent that they become disconnected from the world.

Psychological flexibility means being open to and accepting of unwanted negative internal events (such as thoughts, feelings and sensations) while continuing to engage in behaviour that reflects your values (that is, how you want to behave in life, such as being a kind person or raising your children with respect and compassion). When you’re more psychologically flexible, you’re more connected with the world and more able to do the things that matter to you. And this seems to be the key problem for people with psychosis — their troubling negative thoughts and emotions overwhelm them to such an extent that they become disconnected from the world.

Many traditional pharmacological or psychotherapeutic interventions for psychosis target symptom reduction as their primary goal. The rationale is that because people are disturbed by their delusional thoughts and difficult emotions, removing or reducing these thoughts and emotions will end the disturbance. This is the medical model approach to psychosis: remove the negative symptoms and you’re once again healthy.

Instead of trying to control and reduce negative cognitions, memories or emotions, ACT focuses instead on changing your relationship with these events. As we discuss in Chapters 9 and 11, the nature of your thoughts and feelings means that trying to control them is doomed to failure. But that doesn’t mean you’re powerless in the face of disturbing psychological content. While you have little direct control over what you think and feel, you can change how you relate to those experiences and therefore what they mean to you (check out the nearby sidebar, ‘Decentring negative events’ for examples). ACT defusion and mindfulness processes are designed to help you do just that.

Applying an Acceptance-Based Intervention

Instead of trying to reduce unpleasant cognitions and psychotic symptoms, ACT works to build openness to and awareness of these experiences so that you can engage in value-based actions. There are good reasons for this. First, you can’t easily change these experiences and, second, it’s well-documented that the presence of psychotic symptoms doesn’t always lead to distress or disturbed behaviour. Psychotic-type thinking is actually quite common, but people don’t tend to talk about it. When surveyed, however, lots of people state that they believe in telepathy, ghosts and telekinesis (moving objects through the power of your mind), for example. Indeed, a survey conducted in the Netherlands found that 4 per cent of respondents regularly hear voices.

ACT uses a range of experiential exercises that help you develop a different relationship with your thoughts and feelings. Through these exercises you come to understand that your thoughts and feelings aren’t always what they seem. You discover that you don’t have to change or get rid of them to live your life. You can live with them rather than live in them. When you reduce the believability of your thoughts and the insistence of your feelings, you can begin to ask what you want to be doing with your life and to set value-based goals to steer you in the right direction.

ACT uses a range of experiential exercises that help you develop a different relationship with your thoughts and feelings. Through these exercises you come to understand that your thoughts and feelings aren’t always what they seem. You discover that you don’t have to change or get rid of them to live your life. You can live with them rather than live in them. When you reduce the believability of your thoughts and the insistence of your feelings, you can begin to ask what you want to be doing with your life and to set value-based goals to steer you in the right direction.

Two of the key focus areas for ACT-based interventions for psychosis are defusion and acceptance.

Defusing from your thoughts

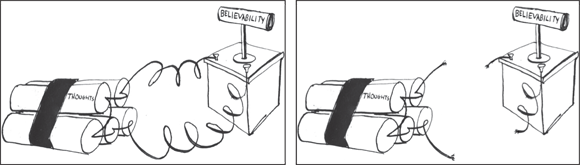

Nowhere is the idea of defusing thoughts more appropriate than in psychosis. People can experience truly explosive thoughts, and if these are allowed to ‘go off’ they can (and do) blow their lives apart. If you’re sitting with lots of little bombs in your head, defusing them is clearly a good idea.

Nowhere is the idea of defusing thoughts more appropriate than in psychosis. People can experience truly explosive thoughts, and if these are allowed to ‘go off’ they can (and do) blow their lives apart. If you’re sitting with lots of little bombs in your head, defusing them is clearly a good idea.

Thoughts aren’t dangerous on their own, however; they need a detonator to make them explode. And that detonator is their believability — check out Figure 19-1. When you believe your thoughts, you provide the detonation that allows them to explode. In contrast, when you take away the detonator of believability, they remain just thoughts — bits of language that float through your head from time to time.

People who experience psychotic-type events typically focus more strongly than normal on their internal world and are more aware of what they’re thinking. When you believe your thoughts to be literally true and to reflect the world as it really is, you’re fused with them. Fusing with your thoughts means you’re more likely to be influenced by their content (Chapter 6 covers fusion in detail). For example, if you fuse with the thought, ‘They’re trying to get me’, you may run away from people or attack them because you feel you really are at risk.

In contrast, if you’re able to defuse from your thoughts, you may simply think, ‘I’m having that thought again, that they’re trying to get me’. The meaning of the thought has now changed from being a supposedly accurate representation of the world to being just a thought. Having a defused relationship with your thoughts creates a small amount of space in which you can decide how you want to respond to them. This little bit of wriggle room is all you need. It creates just enough time to notice your thoughts and in that moment reduce their believability and avoid detonation.

Try the following exercise to experience directly noticing your thoughts and changing their meaning as a result of doing so.

Picture your mind as a bully who wants to be in charge. The more you struggle and push it away, the more it pushes back and tries to dominate you. This process is exhausting and even though you’ve tried so very hard to get rid of it over the years, it just won’t go. You’ve also tried a different approach: doing what it tells you and believing everything it says. However, while not fighting against it provides some relief, doing what it says can get you into serious trouble. You can find yourself doing things that you don’t really want to do and not doing things you actually do want to do.

Picture your mind as a bully who wants to be in charge. The more you struggle and push it away, the more it pushes back and tries to dominate you. This process is exhausting and even though you’ve tried so very hard to get rid of it over the years, it just won’t go. You’ve also tried a different approach: doing what it tells you and believing everything it says. However, while not fighting against it provides some relief, doing what it says can get you into serious trouble. You can find yourself doing things that you don’t really want to do and not doing things you actually do want to do.

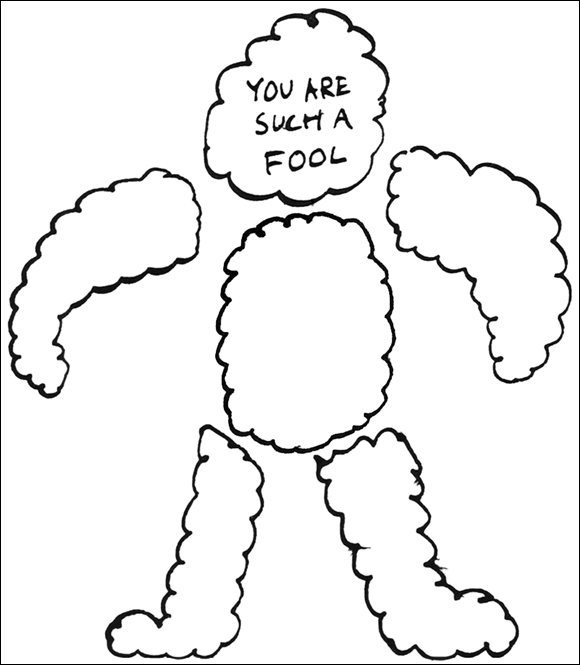

You can get so caught up trying to avoid, resist or fight against the content of your mind that you don’t notice what these experiences actually are — merely thoughts and images going through your head. Stop and take a closer look. The mind is like a monster containing speech and thought bubbles. As a whole, the bubble monster appears scary — but really it’s just a collection of words.

Take a look at your own bubble monster. Consider what words you’d write in Figure 19-2; we’ve filled in one bubble as an example.

How does looking at your bubble monster, who likes to bully you and push you around, make you feel? Do any thoughts come into your head? Are they the bubble monster’s thoughts or yours?

Now that you recognise that your mind is just a collection of words and phrases, sometimes saying nasty or strange things, you have a choice. You can do what you did before and go back to fighting and listening to it. Or you can simply let it be. You can’t actually get rid of your mind — and it’s often very useful! — but letting it be means you can now get on with doing what you want to do with your life.

This exercise enables you to no longer see thoughts, hallucinations and delusions as factual or real but instead as just language produced by your mind. Your mind will go on ‘talking’ (that is, thinking, evaluating, criticising and so on) because that’s what your mind does, but you can now choose whether or not to respond to the content of what’s said.

Being able to distance yourself from your own verbal content becomes an alternative to trying to stop, escape from or avoid it. As a result you can behave more flexibly in the presence of distressing thoughts, hallucinations and delusions, and spend your time getting on with value-based living.

Being able to distance yourself from your own verbal content becomes an alternative to trying to stop, escape from or avoid it. As a result you can behave more flexibly in the presence of distressing thoughts, hallucinations and delusions, and spend your time getting on with value-based living.

Accepting your feelings

Psychosis can also involve experiencing difficult feelings in your body or disturbing mental images and memories. The nature of these events means it’s quite natural that you want to avoid them. But being unwilling to remain in contact with unwanted internal events (memories, feelings and mental images) can lead to ultimately futile efforts to change or avoid them. That unwillingness is the basis of experiential avoidance, which we cover in Chapter 9.

Trying to avoid your thoughts, feelings, memories or bodily sensations is a waste of your time and energy because you don’t have enough control over them to make this strategy successful in the longer term. How you feel depends on your past, which means that you can’t change your emotional experience in the here and now. All you can do is give yourself new experiences so that you can feel differently in the future.

Trying to avoid your thoughts, feelings, memories or bodily sensations is a waste of your time and energy because you don’t have enough control over them to make this strategy successful in the longer term. How you feel depends on your past, which means that you can’t change your emotional experience in the here and now. All you can do is give yourself new experiences so that you can feel differently in the future.

The situation is similar for your memories and thoughts. These are linked via arbitrary relationships to things all around you over which you have little or no control, which means that your memories or mental images can be pulled into your consciousness at almost any time. Everyone’s experienced moments when things just pop into his mind. Sometimes you notice the event that led to it, but often not. When you notice the event that prompted a memory or thought, you may then want to avoid similar events in future. Unfortunately, you can’t shut out the world completely and memories, thoughts or images will always find a way to emerge in your life.

Sadly, even though we can’t avoid our internal psychological content, that doesn’t stop us from trying. We’re so culturally conditioned to believe that we can control how we think and feel that we battle on trying to do so even when we can see it isn’t working. When we fail to exert control we see it as something else we’re bad at and criticise ourselves for not being clever or strong-willed enough.

Not only is experiential avoidance ineffective, it actually makes things worse for two related reasons:

Not only is experiential avoidance ineffective, it actually makes things worse for two related reasons:

- Research indicates that the more you try to control your emotions and internal experiences, the more you focus on them and the more dominating they become.

- Every second that you spend trying to control your emotional and internal experiences can’t instead be used for doing the things you care about.

Rather than avoiding or rejecting what you feel and sense, ACT shows you how to accept these experiences. Not because you want to, but because when you’re willing to have them you’re no longer wasting time in a futile battle to be rid of them. In the same way that you can discover how to accept your thoughts, you can also develop the skill of remaining in contact with unwanted, negative and/or distressing emotions and sensations.

ACT uses a range of experiential and mindfulness exercises to help you develop this skill. Doing so isn’t easy, but evidence does show that it’s possible. Research conducted by Patty Bach at the University of Central Florida, for example, demonstrated a 50 per cent reduction in hospital readmissions for people with psychosis following engagement in an ACT programme. Even people with multiple, complex histories of psychosis can develop these skills so that they can come to relate differently to their thoughts and other internal experiences.

Try the following short mindfulness exercise to practise being present with difficult thoughts and feelings. Your task is to notice what you’re experiencing without trying to control or alter it in any way. While a simple idea, it can seem quite radical if you have a long history of trying to control or minimise unwanted cognitions and emotions. Remember that the ability to be present with your experiences is a skill that you need to practise in order to be good at. And the more you practise, the better you get.

This exercise takes about ten minutes, but you can speed it up or slow it down depending on how much time you have. Follow these steps:

This exercise takes about ten minutes, but you can speed it up or slow it down depending on how much time you have. Follow these steps:

- Find a quiet place to sit or lie down in a comfortable position, making sure that you’re not restricted by your clothing.

- Take a few deep breaths and, when you’re ready, close your eyes.

- Focusing on your feet, pay attention to any physical feelings you notice. Are you aware of pain, discomfort, coolness, warmth, tension, tightness, for example? Simply pay attention to what you can feel and any sensations you have.

- Be aware of your mind making judgements about how you’re doing, but don’t respond to them.

- Repeat this process for the rest of your body, moving slowly upwards through your thighs, stomach, back and so on until you reach your forehead.

- When you’ve finished concentrating on your forehead, work back down your body in reverse, noticing the sensations you experience and the judgements your mind makes until your awareness finally settles back on your feet.

How did you get on with this mindfulness exercise? Were you able to be present with your body and the sensations that arose within it? Did you find yourself struggling with them or being open and accepting of them?

Exercises like this help you notice and accept your experiences for what they are. They may not be pleasant and you may not want them, but they exist nonetheless. When you’re willing to accept all experiences, positive and negative, however, they’re no longer the basis for struggle and distress.

Exercises like this help you notice and accept your experiences for what they are. They may not be pleasant and you may not want them, but they exist nonetheless. When you’re willing to accept all experiences, positive and negative, however, they’re no longer the basis for struggle and distress.

Psychosis is a serious and frightening experience for individuals and their friends and family. ACT can support people experiencing delusions, hallucinations and confused thoughts by showing them how to defuse from them. It also helps them to accept difficult feelings so that they exert less influence over their behaviour.

Psychosis is a serious and frightening experience for individuals and their friends and family. ACT can support people experiencing delusions, hallucinations and confused thoughts by showing them how to defuse from them. It also helps them to accept difficult feelings so that they exert less influence over their behaviour.

Exploring what psychosis means

Exploring what psychosis means Defusing from psychotic thoughts

Defusing from psychotic thoughts Discovering how to accept the symptoms

Discovering how to accept the symptoms While we do present some proactive ideas and options, these shouldn’t be seen as an actual intervention programme for someone experiencing psychosis. If you need to access such a programme, seek advice from your GP.

While we do present some proactive ideas and options, these shouldn’t be seen as an actual intervention programme for someone experiencing psychosis. If you need to access such a programme, seek advice from your GP. Psychosis describes a condition involving three related experiences:

Psychosis describes a condition involving three related experiences: ACT uses a range of experiential exercises that help you develop a different relationship with your thoughts and feelings. Through these exercises you come to understand that your thoughts and feelings aren’t always what they seem. You discover that you don’t have to change or get rid of them to live your life. You can live with them rather than live in them. When you reduce the believability of your thoughts and the insistence of your feelings, you can begin to ask what you want to be doing with your life and to set value-based goals to steer you in the right direction.

ACT uses a range of experiential exercises that help you develop a different relationship with your thoughts and feelings. Through these exercises you come to understand that your thoughts and feelings aren’t always what they seem. You discover that you don’t have to change or get rid of them to live your life. You can live with them rather than live in them. When you reduce the believability of your thoughts and the insistence of your feelings, you can begin to ask what you want to be doing with your life and to set value-based goals to steer you in the right direction.

Picture your mind as a bully who wants to be in charge. The more you struggle and push it away, the more it pushes back and tries to dominate you. This process is exhausting and even though you’ve tried so very hard to get rid of it over the years, it just won’t go. You’ve also tried a different approach: doing what it tells you and believing everything it says. However, while not fighting against it provides some relief, doing what it says can get you into serious trouble. You can find yourself doing things that you don’t really want to do and not doing things you actually do want to do.

Picture your mind as a bully who wants to be in charge. The more you struggle and push it away, the more it pushes back and tries to dominate you. This process is exhausting and even though you’ve tried so very hard to get rid of it over the years, it just won’t go. You’ve also tried a different approach: doing what it tells you and believing everything it says. However, while not fighting against it provides some relief, doing what it says can get you into serious trouble. You can find yourself doing things that you don’t really want to do and not doing things you actually do want to do.