IN THE MID-1970S, NEST began to take form. Central direction would come from the Nevada Operations Office, in the persons of Mahlon Gates and his deputy, Troy Wade. Wade, described in one account as “a thin, athletic-looking man with a rather serene, narrow face trimmed by a small, black goatee,” had joined the weapons test program at the Nevada Test Site in 1958 as an employee of Reynolds Electrical & Engineering. He went to work for Lawrence Radiation Laboratory in 1961 and the AEC in 1968. In 1974, Wade was the assistant manager of the Nevada Operations Office.1

NEST headquarters, or at least the repository of much of its equipment, was the Remote Sensing Laboratory at Nellis Air Force Base. For each laboratory or contractor that was part of the program, there was a senior representative to the search team. At Los Alamos it was William Chambers, while Bill Myre and Duane C. Sewell held those positions at Sandia and Lawrence Livermore, respectively. Sewell had entered the nuclear field in 1940 when, as a graduate student at the University of California at Berkeley, he began working for Ernest Lawrence. After the United States was dragged into World War II, Sewell went to work on uranium enrichment, separating U-235 from natural uranium. From Berkeley, he moved to Oak Ridge for the remainder of the war. At war’s end Sewell headed back to Berkeley, where he was asked to manage the assembly and initial startup of the 184-inch cyclotron. In 1952 Lawrence requested that Sewell, Herbert York, and a small group of physicists start a branch laboratory at Livermore, California, which would eventually become Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. While at Livermore, Sewell helped develop the capability to respond to nuclear accidents, such as Project Crested Ice in 1968.2

EG&G’s senior representatives were Jack Doyle and Harold “Hap” Lamonds. Doyle, about thirty-five years old at the time, had left Texas for Las Vegas in 1964 to work on computer applications in an effort to employ nuclear power to propel American rockets to other planets. After that program was terminated, he moved over to EG&G, where he managed the company’s emerging effort to utilize aerial measuring systems to map the natural radioactivity of the earth’s surface. It was Doyle’s aircraft that was used to locate the Athena missile in Mexico. Lamonds, the former head of the Nuclear Engineering Department at North Carolina State University, had designed and built most of the instrumentation for the nuclear reactor at N.C. State–the first reactor on a college campus. Of even more relevance for an organization such as NEST, he had designed and built a very advanced radiation counting device.3

Participating in NEST, for both the senior representatives and other personnel, did not mean giving up their day jobs. Those at the labs and EG&G who were asked and accepted the offer to become part of the team continued their daily work in weapons design, health physics, or some other discipline, knowing that they might be told to pack a bag and head off for some distant location from which they might never return.

But their first call-out would be relatively close to home, especially for those at Livermore, and involved no real risk. It was the first NEST exercise, held at San Francisco International Airport and designed to test the group’s ability to operate in a real working environment without “letting anyone know you were there,” recalls William Chambers. Care was taken to be sure that if a detection device was hidden in a tool box, the person carrying it had to look like a workman, whereas if the device was in a briefcase, it had to be in the hands of a “staff man.”4

The suitably disguised NEST personnel patrolled the airport terminals and ramps. It was done with the knowledge of airport officials, because, as Chambers recalls, “even in those days you couldn’t just wander around.” What team members were looking for were actual radiation sources that had been placed in the airport, not the plutonium or enriched uranium that would be employed in a nuclear device but very weak sources that would not pose health and safety problems.5

In the mid-1970s, as NEST was just beginning to coalesce, the threats of nuclear extortion and nuclear terrorism were topics of concern to many in the U.S. government and the think tanks it funded. One issue was whether extortionists or terrorists could acquire a sufficient amount of plutonium or highly enriched uranium (HEU) and build a bomb. Potential material for a bomb could be acquired in a variety of ways.

Weapons-grade highly enriched uranium, consisting of at least 80 percent U-235, is the most likely fissile material to be used, or least desired, for building a homemade bomb. It allows for the simplest design—a gun-type weapon in which one subcritical mass of HEU is fired into a target mass, resulting in a nuclear detonation. Plutonium is an alternative but would require construction of a more sophisticated implosion weapon, since a gun-type weapon employing plutonium would likely set off only a messy fizzle, owing to the rate of spontaneous neutron emission from plutonium.6

Fissile material could be covertly siphoned off from reactors or overtly hijacked during transportation (which would increase the credibility of the threats that followed). As Robert Selden of Lawrence Livermore Laboratory, and one of the participants in the Nth Country Experiment, explained to the unpleasantly surprised representatives of several foreign atomic energy authorities in November 1976, reactor-grade plutonium would be highly useful in building a bomb.7

Of course, without the ability to build either a gun-type weapon or an implosion device, stolen fissile material could still be used in a far less dangerous dirty bomb. But some experts believed that a privately built atomic bomb was by no means impossible. The Special Safeguards Study, directed by David Rosenbaum for the Nuclear Regulatory Commission in 1974, noted the “slow but continuing movement of personnel in and out of the areas of weapons design and manufacturing” and that forced departures “can create very strong resentments in the people involved.” And Ted Taylor, the former Los Alamos physicist who was the primary subject of John McPhee’s The Curve of Binding Energy, believed that there was sufficient information in the public domain—works such as The Los Alamos Primer and the Sourcebook on Atomic Energy—that clandestine manufacture of a nuclear bomb was possible and a bigger threat than reactor accidents or nuclear war. Robert H. Kupperman, the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency’s chief scientist, offered his opinion that “there is no doubt that mass annihilation is feasible, and resourceful, technically-oriented thugs are capable of doing it.”8

In April 1976 the Energy Research and Development Administration (ERDA), which had replaced the Atomic Energy Commission that year, released a fact sheet on the results of a study it had conducted along with its weapon laboratories. The fact sheet reported that “the conclusion reached was that it would be FOOLHARDY FOR ANY PERSON OR GROUP TO TRY TO MAKE A ‘BASEMENT ATOMIC BOMB.’ ” The fact sheet went on to state, “It is unlikely that an inexperienced group, however determined, could succeed in making a crude nuclear explosive device in a few weeks, or even in a few months” and “The more hurried the effort, the greater would be the risk of a fatal accident.” The challenges faced by a group seeking to build a nuclear device would include obtaining the critical mass of fissionable material, the need for individuals with “more than elemental knowledge of physics, mechanical skills, and high explosives,” and good machine shop facilities. The members of the group would also “be exposed to great danger” from the nuclear materials, the risk of a criticality accident, and the handling of high explosives. It was an attempt, recalls Victor Gilinsky, who at the time was an official at the NRC, “to scare bomb makers.”9

Others wondered whether terrorists would bother, whether even if they could build a bomb it would suit their plans to build and use one. In 1975, one of those skeptics was Brian Jenkins, a thirty-three-year-old analyst with the RAND Corporation in Santa Monica, California. RAND could trace its origins back to 1946, when it grew out of Douglas Aircraft’s Santa Monica research laboratories. Jenkins was four years old at the time, living in Chicago. By 1975 he was working at RAND, after graduating from high school at age fifteen, entering UCLA as a gifted student, and joining the Green Berets in 1965. Service in the special forces took him to the Dominican Republic and Vietnam.10

Jenkins would go on to become a well-known expert on terrorism, producing book chapters and reports for RAND and commercial publishers, appearing on television, working as an officer of the investigative firm Kroll Associates, as well as serving on or working for the White House Commission on Aviation Safety and Security and the National Commission on Terrorism and, eventually, consulting for NEST. His interest in terrorism began no later than January 25, 1968, when he started entering data on three-by five-inch index cards about an anti-Castro group’s terrorist attack. Eventually, his data base would fill hard drives.11

By 1975 the threat of nuclear terrorism had attracted his attention. In November he testified before the California State Assembly and turned his testimony into a RAND paper: “Will Terrorists Go Nuclear?” Jenkins characterized potential nuclear terrorists as including extortionists, fanatical environmentalists, and disgruntled employees, and their actions as encompassing the spreading of radioactive material, attacks on nuclear reactors, as well as detonation of a nuclear device. However, part of his analysis focused on terrorists with a political agenda, and the possibility of their seeking to destroy large numbers of people via an atomic explosion. Jenkins concluded that this did not seem to be a very likely scenario.12

He argued that “terrorism for the most part is not mindless violence” but “a campaign of violence designed to inspire fear, to create an atmosphere of alarm which causes people to exaggerate the strength and importance of the terrorist movement.” He went on to explain that “since most terrorist groups are small and have few resources, the violence they carry out must be deliberately shocking . . . Terrorism is violence for effect . . . Terrorism is theater.”13

Jenkins argued that it would be relatively rare for terrorists to try to kill large numbers of people or cause widespread damage. “Terrorists,” he wrote “want a lot of people watching, not a lot of people dead.” That might explain, Jenkins thought, why, aside from potential technical difficulties, they had not already used chemical or biological weapons or even conventional explosives in a manner that would produce mass casualties: “mass casualties simply may not serve the terrorists’ goals and could alienate the population.” Therefore, Jenkins believed that “the assembly and detonation of a nuclear bomb appears to be the least likely terrorist threat.”14

Jenkins also was skeptical that terrorists would be interested in the deliberate dispersal of radioactive material, by detonation of a dirty bomb or another device. Many of the consequences of such an attack—more serious and protracted illnesses, a statistical rise in the mortality rate, and, in the end, an increase in the number of birth defects—did not fit the pattern of terrorist attacks. Terrorists wanted immediate and dramatic effects from a handful of violent deaths, “not a population of terminally ill, vengeance-seeking victims.”15

Jenkins’s views were echoed, to a certain extent, by the authors of a study from the U.S. Congress’s Office of Technology Assessment (OTA) in 1977. They noted that no single terrorist incident in the previous fifty years had killed more than 150 people, and that “incidents involving more than 20 deaths are rare.” They also commented that “on the basis of the historical record and the theory of terrorism, it is not clear that causing mass casualties or widespread damage is attractive to a terrorist group.”16

At the same time, the congressional authors noted that there was substantial disagreement among experts concerning the likelihood that terrorists would seek to acquire a nuclear capability. In addition, they commented that there was no assurance that terrorists would continue to behave in the future as they had in the past. With regard to nuclear terrorism, they concluded that if “non-state adversary groups with the will to threaten or carry out large-scale violence do appear, they may choose nuclear means, even if it is somewhat more difficult, because they understand the public fascination and fear, and know that the nuclear threat or act will have the greatest impact.”17

But while experts were debating whether terrorists and extortionists could build a nuclear bomb and whether terrorists would use one, people continued to claim to have such weapons and be willing to employ them unless their demands were met. Ten months before Jenkins’s testimony, Los Angeles received a threat in writing, including a drawing of a one-megaton hydrogen bomb (which Ted Taylor believed would be impossible for a non-government organization to build) supposedly from the radical Weather Underground. The letter accompanying the drawing claimed that bombs had been planted in three buildings. But nothing was found and nothing exploded.18

Six months later, in July 1975, there was another threat to kill a large number of people using a nuclear weapon. This one came not from politically motivated terrorists but from apparent extortionists. The letter claimed, “We have successfully designed and built an atomic bomb. It is somewhere on Manhattan Island,” and offered proof in the form of an accompanying one-eighth-scale drawing. Then came the threat and the warning: “We have enough plutonium and explosives for the bomb to function. This device will be used at 6:00 P.M. July 10 unless our demands are met. Do not notify the public. This will result in hysteria and the use of the bomb.”19

The fourteen-year-old who threatened Orlando wanted only $1 million, and those threatening Boston asked for a mere $200,000. Whoever was threatening New York seemed to be aiming for a far greater payoff: the price to avoid a nuclear detonation in Manhattan was $30 million. The money was to be paid in small, unmarked bills, out of sequence, drawn from twelve Federal Reserve banks.20

But it wasn’t the amount of money that concerned federal officials—it was the drawing. It was “sophisticated, precise, and obviously made by someone who had more than a passing acquaintance with nuclear physics,” according to one account of the episode. In compliance with instructions, the FBI placed an announcement about a truck accident in Vermont on the radio news to let the extortionists know that their demands would be met. A package large enough to contain the $30 million was placed at the drop site, in Northampton, Massachusetts, that had been specified in the note.21

As in Boston, a year earlier, the FBI did not use real money. The package was a dummy. And as in Boston, no one ever came to pick it up. Whether the letter represented a serious attempt to become rich through nuclear blackmail remains a mystery. The extortionists, or hoaxers, were never heard from again.22

During the very month that Jenkins appeared before the state assembly in Sacramento, a note threatening to detonate a nuclear bomb unless a large sum of money was given to the extortionist was delivered a few hundred miles to the south. The recipient was Fred L. Hartley, the chairman and president of Union Oil Company of California. Union Oil had been created in October 1890 from the mergers of three California oil companies: Sespe Oil, Torrey Canyon Oil, and Hardison & Stewart Oil. Hartley, a native of Vancouver, British Columbia, came on the scene in 1939, not as an executive but as a refinery maintenance worker with only $25 in his pocket, a “cast-iron will,” and a knack for chemical engineering. By the 1950s he was moving the company into the business of geothermal power and the refining of oil from crushed shale. In 1964 he became president and chief executive officer, positions that he would hold for twenty-four years. During that time, he initiated a merger between Union Oil and Pure Oil of Illinois as well as expanded the company’s operations to South Korea, Thailand, and the North Sea.23

In June 1974 the New York Times reported that Hartley’s company had developed a new process for extracting oil and gas from shale, a process expected to increase the company’s reserves by 15 percent. Later that year the paper also reported that California Attorney General Evelle Younger filed an antitrust suit against the company, which charged it with restraint of trade for allegedly threatening to cancel a franchise of two service station operators unless they stopped selling products not purchased from Union Oil.24 But the threat from the state of California was nothing compared to the one in the letter that arrived in the fall of 1975.

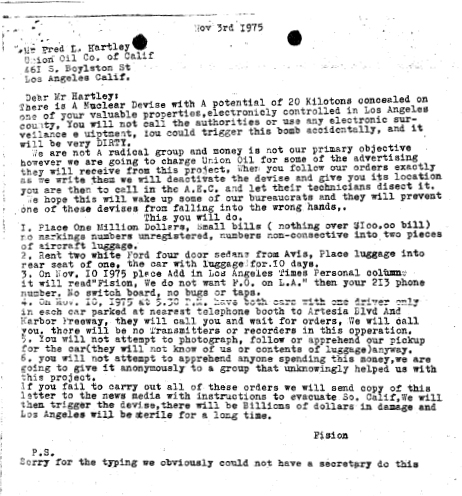

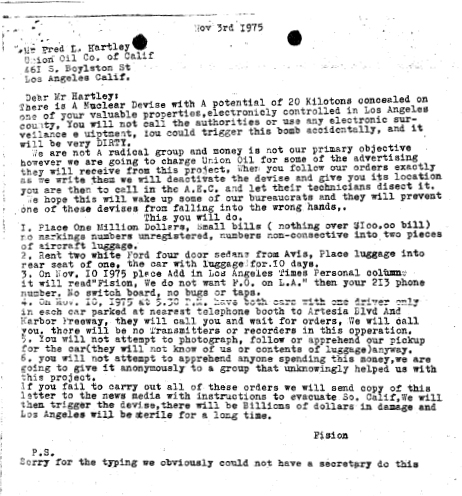

On November 4, Hartley received a special delivery letter marked “PERSONAL,” and subsequently determined to have been mailed from Long Beach, at the company’s office on South Boylston Street in downtown Los Angeles. The typed letter, slightly less than a page in length and dated November 3, claimed, “There is a Nuclear Device with a potential of 20 kilotons concealed on one of your valuable properties, electronically controlled in Los Angeles County.” It also told Hartley, “You will not call the authorities or use any electronic surveillance e[q]uipment, You could trigger this bomb accidentally, and it will be very DIRTY.”25

Extortion Letter to Fred Hartley (Source: Federal Bureau of Investigation)

The author, who used the designation “Fision [sic],” went on to explain: “We are not A radical group and money is not our primary objective” but “we are going to charge Union Oil for some of the advertising they will receive from this project.” The author promised that if Hartley’s company followed orders precisely, “we will deactivate the devise [sic] and give you its location.” Union Oil was to then call the AEC and “let their technicians disect [sic] it.” To add to the confusion, prior to the payoff instructions, Fision wrote, “We hope this will wake up some of our bureaucrats and they will prevent one of these devises from falling into the wrong hands.”26

What followed were five-part instructions. Union Oil representatives were ordered to place $1 million in small bills in two pieces of airport luggage, rent two white Ford four-door sedans from Avis, and purchase an ad in the November 10 Los Angeles Times personal column reading, “Fision, We do not want F.O. on L.A.” and providing a direct 213 phone number through which to reach Hartley. Then on November 10, the representatives were to drive the rental cars to a specific telephone booth to await instructions. The instructions included the usual boiler-plate language from extortionists and kidnappers about no use of surveillance equipment and no attempts to follow or apprehend.27

The author also instructed Hartley that no attempt should be made to arrest anyone spending the money, as “we are going to give it anonymously to a group that unknowingly helped us with this project.” Fision warned that if the instructions were not followed, “we” would send a copy of the letter to the news media “with instructions to evacuate So. Calif” and “then trigger the devise [sic].” The results, the author warned, would be “billions of dollars of damage” and “Los Angeles will be sterile for a long time.” In a postscript, Fision offered an apology of sorts for the poorly punctuated, frequently misspelled letter: “Sorry for the typing we obviously could not have a secretary do this.”28

What Hartley’s immediate response was is not known, but given that he was described as a “gruff-barrel-chested man” whose yacht was named “My Way” and who told reporters that his retirement plans were “none of your damn business,” it was probably unprintable in the New York Times or any other family newspaper.29

Union Oil’s security office alerted the FBI on November 4, which called NEST. Altogether, forty NEST members along with search equipment headed to Los Angeles. Dressed in business suits and carrying radiation detection devices in ordinary briefcases, some of the NEST personnel searched on the ground and from the air six major Union Oil installations—including oil plants and offices—in the Los Angeles area, beginning on November 6. Included were the Los Angeles Refinery, a 450-acre complex in Wilmington, California; the Los Angeles Terminal, a 30-acre site in Los Angeles; the 94-acre Torrance Tank Farm, also in Los Angeles; the 15-acre Harbor Tank Farm in San Pedro; and Union’s home office building on South Boylston. They also checked Hartley’s home. The searches took three days. They did turn up a small chunk of raw uranium that a company official kept in his desk as a souvenir.30

But there was a brief period when the team thought they might have located something that could cause serious harm. NEST official Jack Doyle recalled that “the guys were out there in their trucks listening to their earpieces. Suddenly one got an intensive reading, looked up and there, about 50 yards away, was a big bulky, unidentified wooden crate resting by a refinery fence. There was a moment of real panic.” However, what the team found was not a nuclear device but a box some repairmen had left behind, sitting atop soil that was emitting natural radioactivity. Before they realized it was nothing threatening, “the searchers had plenty of time to think about the implications of their job,” according to an early account of NEST’s activities.31

Despite NEST personnel not having found any devices, or maybe because they did not, Union Oil placed the requested personal message in the Los Angeles Times on November 10. Rather than using the number in the ad, Fision phoned the pay phone specified in the November 4 letter sometime after 3:30 in the afternoon. Two bureau cars equipped with radios and containing dummy payoff packages were waiting. The FBI agents were ordered to another pay phone, where they received a second call. This one instructed that the vehicle with the payoff money be left in a parking lot at the California Yacht Anchorage in San Pedro, which was done at about 7:05 that evening. During the second call, the agents noted that an individual at a nearby phone booth concluded a phone call at the same time as Fision. Ignoring Fision’s instructions, they trailed the suspect, who was driving a new car without license plates or a temporary operating permit, first to the Black Forest Restaurant on Pacific Coast Highway and then to the same parking lot where the bureau left the car with the dummy payoff. That car was then placed under “discreet surveillance.”32

The driver, according to an FBI account, “disappeared into the boat storage area of the harbor” where he “was presumed to have boarded one of the hundreds of luxury boats stored in this area.” The next morning the bureau was able to determine that the car was owned by a leasing company and used by one of its salesmen—Frank James, who was sixty-two years old at the time. When the agents, including one who had observed the driver of the license plate–free car and the one who had received both phone calls from Fision, confronted James on his boat, he denied any involvement. Both concluded he was lying.33

James did agree to let the agents search his boat and car, which yielded a typewriter, and turned over the clothes he claimed to be wearing the previous evening. He also agreed to have his fingerprints taken. A search of the clothes failed to reveal anything of interest to the agents. They also sent samples of two pages, typed by James on the typewriter, to the FBI laboratory. The lab tried but failed to match latent prints from the pay phone where agents believed Fision made his calls and from the extortion letter and envelope to those of James.34

While waiting to be fingerprinted at the local FBI office, James would tell the special agent-in-charge, Elmer F. Linberg, that he realized he was in serious trouble. And indeed he was—but not immediately. Although he denied that the voice on the tape made of Fision’s February 10 phone calls to the FBI agents was his, the bureau found others who believed the voice did or might belong to Frank James. However, after reviewing the case against James in late January 1976, the Indictment Committee of the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Los Angeles declined to prosecute.35

But the FBI effort to link James to the extortion attempt continued, including lining up more associates of James who believed that the voice of the extortionist sounded like that of James. One, after hearing the tape recordings, told the FBI, “It sounds like Frank James to me.” Bureau interviews also began to reveal possible motivations for James’s actions. A relative of James reported that the suspect was in financial difficulty and worried by his wife’s medical problems.36

Eventually the bureau’s efforts led to a three-count indictment of James, charging him with having sent the extortion letter and making the two telephone calls threatening nuclear destruction if the demand for $1 million was not met. Shortly after the indictment was issued, an official of the Union Oil security department provided the FBI a package of news articles and documents suggesting an additional motive: a conflict between Union Oil and the residents near the Union Oil tank farm on 22nd Street in San Pedro.37

On October 8, 1976, in U.S. District Court in Los Angeles, James was found guilty on all three counts of the indictment. On November 1, the presiding judge, William Gray, sentenced James to a remarkably light sentence: six months in jail, followed by three years of probation. In September 18, 1978, after Gray denied two motions on behalf of James, he ordered the convicted extortionist to report in one week to begin serving his sentence.38

In July 1976 the United States observed its bicentennial. Events commemorating the signing of the Declaration of Independence and the War of Independence actually started on April 18, 1975, when President Gerald Ford arrived in Boston to light a third lantern at the city’s Old North Church, to symbolize the beginning of America’s third century. The following day he delivered a speech commemorating the 200th anniversary of the battles—of Lexington and Concord—that launched the American Revolution, and the Post Office issued a “US Bicentennial” postage stamp.39

But the major celebrations took place on Saturday and Sunday, July 3 and 4, 1976. Coverage, in the pre–cable news era, was limited to the three major networks and local stations, but it was extensive. CBS Evening News anchor Walter Cronkite hosted fourteen hours of coverage called “In Celebration of US,” while NBC devoted ten hours to the “Glorious Fourth” along with other programs. Viewers could also watch the “Great American Birthday Party” on ABC. On July 4, a substantial fleet of tall-masted sailing ships gathered in New York City. The celebration also included fireworks in the skies over several major American cities, including the nation’s capital. President Ford presided over the nationally televised Washington fireworks.40

The ceremonies went off without incident. But there had been concern inside the national security establishment that individuals or groups far less enthusiastic about America’s history might be planning their own fireworks display, one that might involve a nuclear device and result in mass mourning rather than celebration. In an April 1976 assessment of nuclear terrorism, analysts at the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) wrote, “The prospect of nuclear-armed terrorists can, in fact, no longer be dismissed.” The same analysts also noted that there would be “major problems . . . involved in the acquisition, storage, transport, and employment of a nuclear device.” Thus, the prospect of a dirty bomb was considered greater.41

There was no hard evidence that such a plan was in the works, but just to be on the safe side, NEST was called upon to provide some reassurance. During June 1976, team members conducted a survey of central Washington, D.C., to measure background radiation, since detecting threatening levels required knowledge of how much and what kind of natural radiation was present on an everyday basis—radiation that might come from Vermont granite, soil, or even a truckload of bananas. Their evaluation of several key facilities produced data that “would have been invaluable in the event of a nuclear extortion threat in the Washington area during the Bicentennial celebration,” according to an official Department of Energy publication.42

If events followed the “Nest Operations Plan” for surveying Washington, D.C., three technicians arrived on June 3 to equip a rented utility van with power and communications systems for the operation. The van was to be used to obtain representative gamma and neutron background data. Any strong gamma signals obtained would be analyzed “to determine principal gamma contributors.” The remaining crew and large detector equipment arrived on Sunday, June 6, on a Martin 404 aircraft.43

Altogether the NEST field detachment consisted of twelve people—the ERDA Nevada on-site manager; a scientific advisor; the NEST logistics officer (Jack Doyle); physicists from Los Alamos, Lawrence Livermore, and EG&G; as well as two pilots, two technical specialists, a communications engineer, and a logistics specialist.44

The drive around downtown Washington, which apparently began on June 8, covered areas around the city’s monuments and memorials—the Washington Monument, Jefferson Memorial, and Lincoln Memorial. The unobtrusive van drove along the Potomac, along North Carolina Avenue, Highway 95, and along Pennsylvania Avenue. The next day, the van targeted New Hampshire, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts avenues. On June 10, the focus was on “special areas” designated by the FBI’s Washington field office, and the following day was devoted to “selected typical dwelling areas.” On June 12, the NEST detachment was to pack up its equipment and return to Las Vegas on the Martin 404.45

The Energy Department had made the operation easier by its decision to establish a NEST presence closer to the nation’s capital, and undoubtedly New York and Boston, a presence that could at least provide a quick reaction force in the event of any future nuclear threat to those cities. As a result, NEST-East had been established at Andrews Air Force Base in Maryland, best known as the site from which Air Force One departs and lands.46

Washington was not the only city where NEST deployed in 1976. It responded to another threat to Boston. A small NEST contingent also went to Spokane, Washington, after the police there received a message on November 23, 1976, threatening ten explosions, each one dispersing ten pounds of radioactive material, and demanding $560,000 in small bills. But there would be no arrests, no payoffs, and no damage.47

When members of NEST patrolled the streets of Washington in June 1976 to measure radiation levels, not only did they do it in secret, they did it as members of a secret organization, for NEST’s very existence was classified. That changed in 1977. During a closed session of the House Armed Services Committee, the panel’s members were told of the team and, presumably, some of what it had done. That was followed by public disclosure in the form of a double-spaced, one-and-a-half-page fact sheet. According to one government official, it “was dropped quietly into a table in the press room at midnight on a Sunday night” in the hope no one would notice.48

However, according to William Chambers the announcement followed the conclusion that “we, the FBI would have to work with local government.” It was apparent, Chambers recalls, that it would not be possible to keep NEST activities classified if the team was called out, since both the local government and police would have to be notified. NEST would have to do some of its work at the unclassified level, and thus they “succumbed to the obvious.”49

The fact sheet announced that “a special group of scientists, engineers, and technicians has been formed by the Energy Research and Development Administration to provide technical assistance to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) in responding to nuclear threats” and that “the group is called the Nuclear Emergency Search Team (NEST).” It went on to inform any readers that the FBI had overall jurisdiction at the federal level, and the Department of Defense was responsible for explosive ordnance disposal.50

It also enumerated six missions for NEST personnel and equipment. They could evaluate the technical credibility of the threat, search for radioactive material, identify the isotope and quantity of radioactive material, assess the probability of nuclear yield or spread of radioactive material, assess the potential for personnel injury and property damage in the event that the device detonated, and assist in the render-safe and disposal operations.51

The fact sheet noted that in addition to ERDA, Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory, Lawrence Livermore Laboratory, Sandia Laboratories, and EG&G were “conducting continuing research and study projects to improve ERDA capabilities in this area.”52

Among the contributions being made at Livermore, starting in 1977, was the Nuclear Assessment Program. Technical and behavioral experts at the lab would assess the nuclear threats—concerning stolen weapons, improvised nuclear devices (INDs), radiological dispersal devices (RDDs), and nuclear reactors—for the Energy Department, NRC, and FBI, and report their conclusions, their rationale, and recommendations. The information they were to provide would cover credibility of the threat, assessment of the device, technical and behavioral profiles, the hazards involved, the urgency of a response, and investigative leads. The assessors at Livermore would check to see if the threat was lifted from some novel or perhaps a work of nonfiction. They also would examine writing style, look for misspelled words, and check for references that would eliminate or enhance their credibility.53

This team was capable of deploying with other NEST personnel, bringing along all known data, critiquing disablement options, and providing updates as the situation changed. It also relied on outside help, such as Dr. Murray Miron, a professor psychology at Syracuse University who specialized in psycholinguistics, specifically “in the language of those men who would use language to threaten others.”54

Scientists at Los Alamos contributed by designing a portable suitcase that could be carried in a car or van and used to detect the neutrons emitted by radioactive material, which along with gamma rays are the only emissions from radioactive material detectable at a distance. The aluminum suitcase, with approximate dimensions of eighteen by twenty-six by twelve inches, and weighing seventy pounds, contained detectors, amplifiers, discriminators, power supplies, batteries, a battery charger, and detection logic circuitry. An alarm system, based on the amount of time between incoming neutron pulses, rather than the number of pulses within a given time period, would alert NEST technicians to the presence of nuclear material.55

In 1978 a second wave of lab and contractor personnel signed up for NEST. One of those was Alan V. Mode, who grew up just outside of Tacoma, Washington, a city of about 145,000 people, and traveled downstate, to attend Whitman College in Walla Walla. His 1962 degree from Whitman was followed by a doctorate in 1965 from the “infamous” chemistry department at the University of Illinois, which turned out three hundred newly minted Ph.D.’s each year. Of the three graduate programs Mode had to choose from, Illinois offered him the most money. He joined Livermore in August 1965, specializing in organic and nuclear chemistry, and began over thirty years of work in nuclear weapons diagnostics. During the course of his nuclear chemistry work, he met NEST members, which eventually led to an invitation to join.56

In October 1978, a congressional office received a package containing a dry brown substance, with a note claiming that it was radioactive. NEST was called in and examined the material. It was dirt. That was only one of several NEST deployments for the year, which had included visits to Buffalo, New York, and Miamisburg, Ohio, in January, May, and August, respectively.57

During that year, the concern for nuclear terrorism reached the highest levels of the Intelligence Community and executive branch. In July, the national intelligence officer for nonproliferation was preparing a presidential briefing on nuclear terrorist threats, and in December the director of central intelligence issued the still-secret Special National Intelligence Estimate 6-78, Likelihood of Attempted Acquisition of Nuclear Weapons or Materials by Foreign Terrorist Groups for Use Against the United States.58

Wilmington, North Carolina, whose population even today is only about 100,000, was the childhood home to many who went on to become famous—most prominently, basketball superstar Michael Jordan. Others who merited the tag “famous” and called Wilmington home as children include the late journalists David Brinkley and Charles Kuralt, boxer Sugar Ray Leonard, Los Angeles Rams quarterback Roman Gabriel, and country music star Charlie Daniels.59

In contrast, among those who have lived or worked in Wilmington who would qualify for the description “infamous” is David Learned Dale, described as five feet ten inches tall, weighing about 180 pounds, with collar-length blond hair, a mustache, and a tan. Many of the one-time residents of Wilmington may have demanded a large sum of money (usually in exchange for their talents), but none, other than Dale, did so in exchange for the return of a hundred pounds of stolen uranium, an act that would result in a call asking for NEST’s help.

On Friday, January 26, 1979, Dale was working as a temporary contractor employee at the General Electric low-enriched-uranium plant located about five miles north of Wilmington on approximately 800,000 square feet of land. The plant employed about sixteen hundred people and operated around the clock between 11:00 p.m. Sunday and midnight Friday. Unlike other days, Dale did more than work the day shift that Friday. At 10:50 that night he returned and entered the plant along with the night shift. Instead of showing his yellow contractor badge to gain admittance, he used his Florida driver’s license, with its blue background. Dale believed that to gain access to the area of the plant he wanted to penetrate, he needed a picture badge with a blue background. His previous successful attempts to enter using his driver’s license had established that plant security was less than the best.60

Once inside the plant, Dale ordinarily would have been guided by gates and fences into a parking area, except that one gate had been removed to allow the installation of truck scales. He was able to continue down the unprotected road to an area next to the building he wanted to penetrate. After entry, he continued on to his usual work area, the Chem Tech Lab, and used his own key to enter. Once in the lab he gathered his protective clothing, a two-wheel cart used to move 55-gallon drums, and a container for shipping chemicals. The container could hold two 5-gallon cans. He then headed for a door leading to a stairwell into the plant’s radiation-controlled area.61

Although the door was normally locked, even though regulations did not require it to be, on the night of January 26 it was slightly open because the locking mechanism had malfunctioned. Once inside, Dale put on his protective clothing and climbed the stairs to the Blend Queue Area. He remove two 5-gallon cans of uranium oxide, carried them down the stairs, and placed them in the shipping container. He then removed his protective garments and retraced his steps back to the Chem Tech Lab. Once back in the lab, he opened a can and removed some of the material he intended to use for his extortion effort. With the two-wheel cart, he transported the remaining material to his car and loaded it in his trunk. He retraced his steps and left the plant just before midnight along with the departing shift, in time to avoid the requirement to sign out if leaving the plant after midnight.62

On Monday, January 29, Randall Alkema, the plant’s general manager, arrived at work sometime after 8:00 a.m. Waiting for him in his office was a letter, marked “personal and private,” that had been found outside by a cleaning woman, and a vial containing, it would subsequently be determined, 2.6 percent uranium oxide.63

The letter, hand-printed in capital letters, ran six pages long. It began by informing its reader that the “vial you are looking at contains a sample of uranium abstracted from your stock in Wilmington” and continued, “We are in possession of 66.350 kilograms. It consists of containers #2602 MO 1024 (35.350 KG) and #2602 MO 1017 (31.000 KG).” The writer went on to explain “Plan A”: on February 1 similar vials would be sent to the NRC, the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS), a variety of antinuclear groups, Ralph Nader, every major newspaper in the country, the White House, “and every Senator or Congressman who has ever expressed doubt about nuclear power.” The result would be “a massive outcry from all quarters” that would force the NRC to order “an immediate shutdown of your plant.” The author went on for another two pages, describing the specific reactions expected from groups such as the UCS and Clamshell Alliance, how the release would destroy the goodwill anticipated from the national conference on energy advocacy set to start on February 2 and would help turn the public against nuclear power. It would be “a resounding defeat for the industry, a disaster for GE in particular, and will destroy your career.”64

But there was “one way and only one way that this can be avoided.” That way involved GE assembling, within forty-eight hours, $100,000 in nonconsecutively numbered used bills—in ten-, twenty-, and fifty-dollar denominations. After the money was delivered, in compliance with the instructions that would follow, the uranium would be returned to Wilmington, the letter promised. The author also warned that the uranium had already been transported a thousand miles away from Wilmington and that “if you make even so much as an attempt to bring in the police . . . Plan B will be implemented automatically.” Plan B involved everything threatened in Plan A, plus the contents of one can would be spread throughout the downtown area of a major city. In addition, the price of the remaining can would increase to $200,000.65

After checking that the containers identified by the extortionist were indeed missing, the general manager notified higher-level GE officials, who passed on the information to the NRC and the FBI’s Atlanta office, which turned the case over to the bureau’s Charlotte office on January 29. The special agent-in-charge in Charlotte requested that the bureau’s Behavioral Science Unit prepare a personality profile, that the letter’s writing style be compared with the writing in the anonymous question/suggestion forms that employees left for management as well as with the style of any previous extortion letters held by the FBI’s laboratory, and that the letter be examined by the lab’s Latent Fingerprint Section.66

A copy of the letter was also sent to Murray Miron, who would try to extract details about an anonymous author from what he or she had written. Miron apparently contacted the Energy Department’s Nuclear Threat Credibility Assessment Group at Lawrence Livermore, the key element of the Nuclear Assessment Program, to obtain additional data to help in his evaluation.67

Miron provided a demographic profile of the “UNSUB” (unknown subject)—a college-educated Caucasian male, between twenty-five and thirty years old, with an interest in commercial activities, the stock market, and corporate affairs—and noted that he accurately assessed the commercial value of the stolen material, “which would not be generally known to the general public.” Miron also concluded that his failure to provide data on the composition of the uranium hexafluoride or indication of its enrichment implied that he “is not trained in nuclear technology or engineering.” He also concluded that “the consistent use of the GE acronym over that of the full name of the company and the absence of justification of choosing the Wilmington plant as the target indicates that UNSUB is employed at that facility” and that the motivational factors did not suggest that the UNSUB was “acting out of resentment or vengeful impulses” and that the “UNSUB is still employed in that facility with a good fitness record.”68

Miron also concluded that despite the letter’s claim that the theft was a group action, “the message content reflects content indicators which point to this as the act of a single perpetrator.” In addition, he considered the assertion that the nuclear material was moved to a distant location improbable and “falsely designated to conceal the fact that the material is, in fact, close by.” Indeed, Miron suggested that the material might be hidden in the plant, with the perpetrator having changed labels and serial numbers on the cans.69

The UNSUB, Miron believed, was above average in intelligence and dedication and “without a doubt a psychopath” who attributes “venal, solely commercial motivations to the officials of GE and the government.” “There is not,” Miron noted, “a single reference to principle or morality within the message.” And there is “no indication that the scheme indicates political activism.” Rather, the plan “is entirely motivated by instrumental monetary considerations.” He doubted that the subject would dispose of the material in the way he threatened, although he might send one or two additional samples to one of the groups named.70

Miron was not the only individual charged with trying to assess the credibility of the threat and determine the identity of the perpetrator. According to one assessment, completed by a staff member of the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory within an hour of the discovery of the note, the threat to distribute samples to Ralph Nader and others was feasible—particularly since the managing editor of the Wilmington Star had already received a plastic vial sealed with duct tape with a skull and crossbones and the word “poison” written in red. The assessment also concluded that the threat probably came from an employee at the plant who was working alone (because of the small amount of money being demanded) and motivated solely by financial gain.71

Several staffers from Lawrence Livermore also produced analyses between January 30 and February 1. A January 30 assessment reported the threat to have a high technical credibility owing to the accurate description of the missing containers and the isotopic assay of the sample. It also suggested that use of the phrase “the bomb to drop” in the extortion letter could imply the nuclear material might be dispersed via an airplane or from a high-rise building. An “operations practicality assessment,” however, completed by an analyst that same day classified the threat as a moderate-confidence hoax because of the apparent flaws in the plan. It was not clear, according to the Livermore analyst, that distribution of samples would force a plant shutdown or result in damage to the industry. In addition, the analyst did not think much of the extortionist’s demand that the money be paid in forty-eight hours or of the threatened consequences of bringing in the police.72

The judgment that the threat could well be a hoax, involving the theft of only a small amount of material, was echoed, to some extent, in the four-hour response by four other analysts from Livermore on January 30. They noted that while “the author of the threat appears to be disposed to carry out the threatened actions . . . his message also contains elements that are consistent with hoaxes—attempting to create a powerful threat from a weak position.” Thus, they concluded that the author was willing to carry out the threat, but they also believed, “with moderate to high confidence,” that “he does not have uranium oxide in more than gram quantities and therefore could not contaminate entire cities as threatened.” The assessment’s authors also agreed with Miron and the Los Alamos assessment that the threatener was probably a plant employee (since he could specify the missing containers, knew the name and phone number of the plant manager, and was able to slide his note under the manager’s door) and was acting alone.73

Such analyses helped narrow the list of suspects—although a review of the credibility assessment effort by Livermore apparently contained a number of criticisms.* In any case, on February 1, the director of the FBI, informed the White House Situation Room that a number of possible suspects had been identified but that the “investigation was now focusing on one prime suspect.” That suspect was David Learned Dale, whose handwriting was judged to match that of the extortion note. That, and other factors, led to his arrest at 3:30 that afternoon for violation of the Hobbs Act—for committing an act of extortion. Dale quickly admitted his guilt and told the FBI that the two missing containers were in a nearby field about three miles from the GE plant. On May 7, 1979, Dale was given a fifteen-year sentence, to be served at the Federal Correctional Center in Butler, North Carolina.74

NEST’s involvement extended beyond helping Murray Miron analyze the content of the extortion letter. On January 31, 1979, NEST representatives were dispatched from NEST-East at the request of the FBI’s Charlotte office. They traveled to North Carolina on their own plane, with a physicist serving as the head of the team. At about 7:30 that evening they arrived at the Wilmington General Electric plant to calibrate assorted radiation detection equipment as well as establish liaison with company personnel and representatives from the Atlanta region of the NRC.75

Starting about 8:00 a.m. on February 1, NEST personnel conducted a sweep of all parking areas at the GE plant, which produced no hits. In addition, they set up a discreet radiation detection checkpoint in the area of the gate controlling access to employees’ vehicles. No unusual levels of radiation were detected. A helicopter equipped with radiation detection equipment arrived in Wilmington too but was not used because of the amount of background radiation present.76

NEST personnel also examined, for signs of radioactive contamination, Dale’s residence and its immediate vicinity, the site where the containers were recovered, the personnel who recovered the containers, and the containers themselves. The containers were checked for alpha-beta contamination as well as gamma radiation.77

NEST’s failure to find the missing uranium did not greatly concern its leaders, since they believed the team would have discovered the stash within forty-eight hours and that discovery was only preempted by the FBI’s quick apprehension of Dale. What was disturbing to NEST officials such as Jack Doyle was that the incident was “a real step up the ladder,” for never before had an extortionist actually possessed nuclear materials. “We began with paper threats that really had no basis in fact in them,” Doyle observed in 1980. “Then we got into a generation of paper threats on which people had really done their homework and turned in some damn credible material. Next we had a couple of incidents where some hardware got out and some garbage men found a couple of homemade plutonium 239 containers—dead ringers for Government issue—in a garbage dump. Then Wilmington. What’s the next step up the ladder? I hate to think.”78

Less than two months after Dale was apprehended, NEST personnel returned to a middle Atlantic state to deal with a nuclear threat. However, the threat came from neither terrorists nor extortionists. Less than a minute after 4:00 a.m. on Wednesday, March 28, 1979, when about 50 to 60 of the plant’s 525 employees were present, several water pumps in Unit 2 of the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant, ten miles southeast of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, stopped working. In the days that followed, equipment failures, inappropriate procedures, human error, and ignorance produced what a presidential commission characterized as the “worst crisis yet experienced by the nation’s nuclear power industry.”79

At 6:30 a.m. that Wednesday, Mike Janowski, a radiation/chemistry technician, walked through the Unit 2 auxiliary building with a portable beta-gamma survey meter and detected rapidly rising radiation levels, the result of a partially uncovered reactor core. Soon he was running down the hall yelling, “Get the hell out!” Shortly before 7:00 a.m. a “site emergency” was declared and the process of notifying state and federal emergency agencies began. What the consequences would be were not clear. Would damage and radiation be confined to the plant or would threatening radiation spread to the surrounding area, putting citizens at risk and requiring evacuation?80

NEST resources had been committed to answering such questions even before the incident occurred. A March 8, 1977, agreement between the ERDA and the NRC called for NEST team personnel and equipment to respond to an emergency involving “NRC licensees,” which included the nation’s nuclear power plants. Before two o’clock on the afternoon of March 28, a Hughes H-500 helicopter, with sophisticated monitoring equipment, landed at the Capital City airport, the command post for emergency operations, with an advance NEST party.81

The particular element of NEST’s capabilities that was needed at Three Mile Island was its aerial measurement system, which could determine how much radioactivity had been emitted into the atmosphere and where it was headed. About an hour later, team member Bob Shipman set out to find out some answers. After he took some background readings, his helicopter began a slow circle toward the plant. It was not long before Shipman’s instruments began to go crazy, and the needles on the meters hit their limits. Shipman shouted to the copter’s pilot to get out of the area.82

Shipman and his pilot began to fly in and out of the invisible plume emanating from the nuclear power plant, the boundaries of which they could identify by the change in readings. In addition, when the helicopter headed back to the airport and away from the plume, the instruments showed only background radiation, indicating the radiation came from noble gases such as xenon, and not the more dangerous fission products such as cesium, iodine, and strontium, which would have stuck to the helicopter.83

The initial NEST contingent would be supplemented with additional personnel flying in from Nevada and replacements for the advance party arriving from NEST-East. Over a dozen NEST personnel would continue to monitor the radiation levels in the vicinity of the power plant and would be able to provide the good news that there was little threat to public safety.84

In the summer of 1979, a NEST team traveled to Idaho—not in response to an extortion or terrorist threat but for one of the many exercises it would take part in over the years. It had been in Idaho two years earlier, at the Idaho National Engineering and Environmental Laboratory, which occupied about 890 square miles in the southeastern Idaho desert. The lab had been established in 1949 as the National Reactor Testing Station, and in 1975 it became the nation’s second largest National Environmental Research Park.85

The Idaho laboratory had been the host for a NEST exercise in August 1977 designated NEST-77. The exercise had been conducted in cooperation with the FBI and Defense Department, which had the primary responsibility for explosive ordnance disposal, and involved about 150 individuals—either participants or observers—at a cost of about $200,000. All NEST would say about the exercise was that it was designed to “evaluate techniques and sensitive radiation detection and other special equipment.” It was somewhat more specific in its “Observer Plan,” which stated that the purpose of the exercise was to focus on “developing the technical aspects of improvised nuclear device (IND) diagnostics and rendering safe, and not serve as a full operational evaluation.” In plainer language, the exercise focused on determining specifics of the device and disabling it.* It was prepared to assure the press and public that “there is no danger to any of the participants, [lab] employees or the public.” The actual exercise involved explosive ordnance personnel neutralizing booby traps and a NEST diagnostic team removing a nuclear source located in a van.86

Two years later, NEST had a new partner for the exercise, the 1st Special Forces Operational Detachment–Delta, better known as Delta Force. Delta had been created in 1977 to give the United States a dedicated counterterrorist unit. While NEST’s scientists could detect the presence of a nuclear device and help disassemble it, they were not expected to forcibly recover it. That could be Delta’s job. Eric L. Haney, a founding Delta Force member, recalls that the unit spent the week prior to the exercise in Idaho Falls, twenty-five miles east of the desert site, where the lab’s Science and Technology Campus was located, “learning about reactors, nuclear materials, and atomic weapons.”87

According to Haney, the exercise involved recovering a stolen nuclear device held by a group of terrorists who were also holding a group of American scientists. He also recalls that “working on this nuclear exercise, we got a bit of start. We found out that our normal rules of engagement didn’t necessarily apply to nuclear materials.” In contrast to Delta’s philosophy that “we would go to any extremes to avoid harming a hostage . . . national policy dictated that when nuclear materials were involved, hostage lives were of secondary importance.” But according to Haney, “we were confident that even in a nuclear incident, we could still save hostages.”88

The decade ended in 1980 with an incident in Washington, D.C., that required NEST’s attention. That event was the work of Tom Falvey and Patti Hutchinson of Greenpeace, the environmental and political organization created by a group of Canadian and expatriate American peace activists in Vancouver in 1970 and originally called the Don’t Make a Wave Committee. In May 1972 it became the Greenpeace Foundation. From the beginning, the foundation’s activities extended beyond protest, the dissemination of information, and peaceful political action. In 1978 and 1979, with a crew of twenty volunteers, the Rainbow Warrior, a ship purchased by Greenpeace in 1978, challenged Icelandic whaling in the north Atlantic. In September 1979, the ship was captured by an Icelandic gunboat. In early 1980 the ship was again detained, off the French port of Cherbourg, while trying to disrupt the transportation of nuclear waste to a reprocessing plant.89

According to a former Greenpeace official, Falvey and Hutchinson arranged to have uranium mine tailings picked up, he believes, from the side of Interstate 80 in South Dakota. Such tailings are by-products of uranium processing and can be obtained at abandoned mine sites. The radioactive material was placed inside a red 55-gallon drum packed in concrete. Also inside the concrete was the sensor from a single geiger counter, whose ticking was amplified through a sound system in the truck.90

During the afternoon of August 21, 1980, four representatives of Greenpeace held an antinuclear demonstration on the sidewalk in front of the White House. They left behind the drum, with its ticking geiger counter, to emphasize nuclear waste piles that it claimed were contaminating the western United States. U.S. Army explosive ordnance personnel carted the barrel off to Kingman Island, in the middle of the Anacostia River and near Washington’s RFK Memorial Stadium. Meanwhile, the FBI called NEST, which dispatched a team to examine the barrel and dismantle it. At 6:45 that evening, NEST advised the FBI by phone that the “device was a hoax,” according to an FBI memo, which also reported that “at no time did this device present a threat to the health of the individuals in the vicinity of the White House.” Another memo reported that NEST advised that “no radioactive material or any other dangerous substance whatsoever was found.”91

Somewhere along the way, possibly as early as the day of the demonstration, some officials apparently came to believe that Greenpeace had claimed to have placed a nuclear bomb in front of the White House—hence the reference to a “device.” Further, several years later, Herb Hahn, program administrator of NEST at Andrews Air Force Base, was quoted in the Washington Post as saying, “They said it was a nuclear bomb, but it was really a recording device.” According to former Greenpeace executive director Steve Sawyer, “We described it as what it was, i.e. radioactive waste. We sued the Post over that particular story, and by way of recompense they printed a very nice feature on us sometime later in their Sunday magazine.”92

*A letter from an official of the Energy Department’s Office of Safeguards and Security to a special agent of the FBI’s Criminal Intelligence Division noted that on page 65 of a Livermore report on the Wilmington, North Carolina, extortion incident, “the continuing problem of credibility assessment communications is identified,” and that his office is “presently considering a proposal associated with improving upon the credibility assessment system.” See Martin J. Dowd, Assistant Director for Security Affairs, Office of Safeguards and Security, Department of Energy, to Special Agent Robert Satkowski, Criminal Investigation Division, Federal Bureau of Investigation, March 2, 1979.

*William Chambers recalls it differently. He described it as the “first field exercise to test operationally all technical functions from search techniques to IND disablement in an integrated way with joint lab/EOD teams.” William Chambers, “Summary: A Brief History of NEST,” October 24, 1995, p. 2.