THE 1980S BEGAN with a rapid succession of nuclear threats, which undoubtedly meant a busy start to the year for the credibility assessment group at Livermore. On January 2, 1980, somebody threatened to detonate a low-yield nuclear bomb in San Francisco. The next two days brought nuclear threats to Buffalo, New York, and Indianapolis. The threat to the capital of Indiana was another one that Ted Taylor would have considered to be particularly implausible, since the author(s) of the threat claimed to have possession not just of a fission weapon but of a five-megaton thermonuclear device.1

Later that year, another threat would result in two members of NEST being called into action, although no one was claiming to have a nuclear device to detonate. The location was Stateline, Nevada, an “unincorporated town” on the eastern shore of the better-known Lake Tahoe. Stateline is known for its casinos, most of which qualify as resorts, and Nevada State Route 207, also known as Kingsbury Grade, which takes a driver up and over a mountain pass. In 1980, the town had at least three prominent resorts, including the Sahara Tahoe, where Elvis Presley performed from 1971 to 1976; Caesar’s Tahoe, which had opened in 1978, with a 40,000-square-foot casino; and the eleven-story Harvey’s Resort Hotel.2

The Wikipedia entry for Stateline lists five “notable” events associated with the town. One is the filming at the MontBleu Resort Casino and Spa, formerly Caesar’s Tahoe, of the 2007 movie Smokin’ Aces, described by the New York Times film critic as “a Viagra suppository for compulsive action fetishists and a movie that may not only be dumb in itself, but also the cause of dumbness in others.” There was even less for the community to be proud of with regard to the remaining four events. They involved an accident and three criminal acts: the death of musician and politician Sonny Bono in 1998 while skiing, the mutilation and murder of a nine-year-old girl in 2000, and the shootout that resulted in the death of one man and injuries to two sheriff deputies in 2005.3 But the most memorable of the notable events predated these, and it involved Harvey’s.

At 5:30 a.m. on August 26, 1980, two musicians and their girlfriends were crossing the parking lot at Harvey’s. In addition to seeing an apparently inebriated woman, they witnessed two men pushing a wheeled platform holding a large gray box with “IBM” stenciled, rather crudely, on its side. Still, despite the crude lettering, one of the musicians was impressed, commenting, “Wow, IBM delivers.”4

Sometime shortly before 6:00 a.m., Bob Vinson, the slot shift supervisor at Harvey’s, noticed what appeared to be a large gray metal box in the small anteroom on the second floor, next to the office for Harvey’s internal PBX (private branch exchange) telephone system, which at the time was valuable for saving money on internal phone calls. There were actually two boxes: a larger one and a smaller one on top, with some switches. All the switches on the top box, except one, were flipped in the same direction. Vinson, along with a janitor who had wandered by, then noticed an envelope addressed to “Harvey’s management.”5

Vinson left to find the shift sergeant for Harvey’s security detail, William Schonfeld, who would soon be ordering the other security guards to secure the second floor. The sergeant also called the hotel’s security chief, directed that the Douglas County sheriff and fire departments be notified, and then went back to the anteroom to examine the box. He later estimated the larger box at about three feet high and wide and more than three feet long, and the smaller box at about a foot square with twenty to twenty-three switches. On each corner of the box was a jack and levels, which showed that it was placed on four pieces of plywood. “It was,” Schonfeld would later remark, “a good piece of workmanship.”6

It was not long before Simon Caban, the security supervisor, and Wayne Watt, a Douglas County police officer, were examining the box and the envelope. After concluding that it was not a letter bomb, they opened the envelope, pulled out a three-page letter, and began to read it. It was only a few seconds after they started that Watt pointed to the box and stated, “That’s a bomb.”7

The two men who had delivered the package were at the back of the building, where a white van was parked behind a construction trailer. They were met by a man in his late fifties, a man with gray hair, a month-old beard, a prominent nose, and a receding hairline who was wearing a cowboy hat, glasses, and a ski jacket. He slid in behind the wheel and asked his two passengers, “How did it go?”8

The men at the receiving end of the question were Willis Brown and Terry Hall, who had no idea that they had just delivered a bomb as part of an extortion plot. The questioner, who had hatched the plot, was John Birges, who had employed Brown and Hall when he ran a landscaping company. Birges, sixty-one years old at the time, had spent nearly nine years in a Soviet hard-labor camp for political prisoners. After being released, he and his wife, Elizabet, had sneaked across the Hungarian border into Austria. They arrived in New Jersey in 1957, but soon were living in California. Birges was also a gambler, having dropped at least $750,000 in Harvey’s Casino. The bomb and extortion threat were his way of trying to recoup his losses and turn a nice profit in the process.9

The target of Birges’s threat was the owner of Harvey’s, seventy-five-year-old Harvey Gross, later characterized in his New York Times obituary as “a gambling pioneer who turned a tiny club into a multimillion-dollar casino empire.” Gross had opened Harvey’s Wagon Wheel in 1944 and then built the first high-rise hotel in Stateline in 1961. It became known as Harvey’s Resort Hotel.10

The three-page letter, written by Birges’s girlfriend, Ella Joan Williams, was a mixture of claims, promises, instructions, and threats—about what was in the large gray metal box, what to do, when to do it, and what not to do. It contained a “Stern warning to the management and bomb squads”:

Do not move or tilt the bomb, because the mechanism controlling the detonators in it will set it off at a movement of less than .01 of the open end of the Richter scale. Don’t try to flood or gas the bomb. Do not try to take it apart . . . In other words, this bomb is so sensitive that the slightest movement either inside or outside will cause it to explode.

This bomb can never be dismantled or disarmed without causing an explosion. Not even by the creator. Only by proper instruction can it be moved to a safe place where it can be deliberately exploded. Only if you comply with the instructions will you [learn] how to move the bomb to a place where it can be exploded safely.11

The letter also warned that the damage, if it were to detonate, would be very significant. “This bomb contains enough TNT to severely damage Harrah’s across the street,” it promised. “This should give you some idea of the amount of TNT contained within this box. It is full of TNT.” The author also suggested that an area within 1,200 feet, almost a quarter of a mile, be evacuated.12

Despite the suggestion that a significant piece of business property be cleared of people, the letter demanded no publicity: “all news media, local or nationwide, will be kept ignorant of the transactions between us and the casino management until the bomb is removed from the building.” What Birges did want was $3 million, and he wanted it within twenty-four hours—“there will be no extension or renegotiation,” the letter stated. It also warned Harvey Gross that “if you do not comply we will not contact you again and we will not answer any attempts to contact us. In the event of a double-cross there will be another time sometime in the future when another attempt will be made. We have the ways and means to get another bomb in.”13

The payoff, the letter directed, would be made by an unaccompanied helicopter pilot, who would receive his initial instructions at the Lake Tahoe Airport late that night—either from a cabdriver or by way of a call to a public telephone at the airport. He was to fly the route instructed and look for a strobe light, indicating where he was to land. There was also a promise if the casino paid the $3 million. The pledge was not to tell the bomb experts how to turn off the device, but how to safely move it to a remote area where it could be detonated without danger to life or property. There would be six sets of instructions, provided at different times: the first provided to the pilot, while the remaining sets could be picked up at the Kingsbury Post Office general delivery window.14

The battalion chief of the Tahoe Douglas Fire Protection District arrived at Harvey’s at 6:30 that morning and was met at the front entrance by his two captains. After reading the extortion letter, they concluded that it contained portions written for the sole purpose of impressing bomb experts such as themselves. A “float switch” was mentioned, along with “an atmospheric switch set at 26.00 to 33.0.” The letter also stated that there were three “automatic timers each set for three different explosion times.”15

The men gathered their diagnostic equipment and carried it upstairs. It included X-ray equipment, a tripod, and sensitive listening devices, which they could use to visualize the inside of the bomb so they could think of a way to disable it. The bomb, resting on the four small plywood squares and the wheels it had been rolled in on, had been cranked up off the floor.16

While the local bomb experts tried to figure out what to do with the bomb, hotel security began an evacuation, which, as might be expected, led to speculation and rumor. Somebody claimed that there was a bomb and it might be radioactive, an assertion based on having heard that a nuclear response team had been spotted going into the hotel. Somebody else pinned the threat on the Iranians, who had been holding U.S. diplomatic personnel captive since the seizure of the U.S. embassy in Tehran the previous November. A third claim was that the bomb was the work of a disgruntled employee, which was a lot closer to the truth, since Birges could be considered a disgruntled customer.17

The fear that the device was far more deadly than one containing only TNT extended beyond random spectators. NEST veteran Alan Mode recalls that there was “at first a strong concern that it was nuclear.” The initial feeling was, according to Mode, that a “NEST kind of response” was needed.18

The Nevada fire marshal was the catalyst in getting NEST involved. His subordinates contacted the Nevada Operations Office, informing its manager that they had what looked like a computer with an extortion note. The operations office told the fire marshal that they could provide X-ray devices that would be more effective than anything possessed by the fire marshal.19

The office also sent two members of NEST. William Nelson recalls that during the afternoon or early evening of August 26, he was informed that the fire marshal was interested in the use of NEST’s advanced X-ray equipment. Nelson, who belonged to a flying club near Livermore, climbed into a Cessna, along with a radiographic technician, and flew to the South Tahoe Airport.20

The two were met by a van and driver, who, according to Nelson, drove “on the sidewalks” to Harvey’s. When the van reached the front of the extortion target, the driver told Nelson and his colleague that the bomb was “right up the stairs” and that they should feel free to go take a look. Nelson, figuring that he had a reasonable chance of survival, took up the challenge. The technician and X-ray equipment followed. X-rays of the boxes showed circuits and relays, what might have been blasting caps, and what might have been a pressure switch. In addition, they showed wires running from the screws on the surface plate of the metal. If unscrewed by even a quarter of a turn, they would trigger the device. There were also trembler switches imbedded in the metal box that would produce a detonation if the bomb were tilted even slightly. Listening to the bomb with amplified stethoscopes revealed an “intermittent whirling noise.” The X-rays also showed a toilet float, which kept the bomb from being defeated by flooding. There seemed to be no way to take it apart, or move it, or flood it. There was no simple way to clip the “red wire” and disable the bomb, Nelson recalled. And the whirring sound might represent a timing device. It was the type of bomb that would become known as a “sophisticated improvised explosive device,” or SIED.21

That night, while experts were considering how to disarm the bomb without the extortionist’s cooperation, Joe Cook—FBI agent and helicopter pilot—took off with a package that appeared, in weight and volume, to consist of $3 million in bills but really contained only $1,000 in actual currency. The FBI also failed to comply with Birges’s demand in a second way: another of its agents was hidden on the helicopter to protect Cook. But there would be no payoff that night because Cook couldn’t locate the strobe light, the result of Birges’s belated acquisition of a battery to power the strobe—only one of several mishaps to befall Birges and the team he had assembled to help him collect his payoff. That team included Birges’s girlfriend and his two sons, John Jr., age nineteen, and Jimmy, age twenty. John Jr. and Jimmy had helped him steal the dynamite for the bomb from a nearby hydroelectric project and had been promised $100,000 to help pick up the money. They also were supposed to drop the bomb off at Harvey’s but backed out after an accident occurred while loading it into the van, forcing their father to recruit Brown and Hall as unwitting replacements.22

While the extortionists were frustrated by their failure to collect the $3 million payoff, the local authorities, Harvey’s management, and nearby casinos were running out of patience. The unresolved threat was driving away customers, both locals and tourists. On August 27 the fire marshal proposed to tie a rope around the device and pull it over. Another idea, proposed by Leonard Wolfson of the Navy’s Explosive Ordnance Disposal facility in Maryland, and which Nelson agreed to, was to build a linear-shaped charge, consisting of C-4 explosive taped to a two-by-four piece of lumber, which would be used to decapitate the bomb—virtually instantaneously separating the smaller box with all the switches from the actual explosive device.23

The C-4 was in stick form, so various technicians softened the material to make it sufficiently malleable to be placed in a shaped-charge liner, which was fabricated later in the morning in a Las Vegas plant. Wolfson and Army ordnance disposal personnel inserted the C-4 into the liner and taped the liner to the two-by-four. There was an inner liner, with an outer layer, made of brass material designed to generate a gas jet formation known as the “Munroe effect”—in which a hollow or void cut into a piece of explosive concentrates the explosive’s energy. A computer and outside experts determined that the standoff area—the distance between the charge and target that is required to allow room for the gas jet to form before it reaches the target—was 8.5 inches. The two-by-four also had to be tilted 1.6 inches to ensure that the gas jet wouldn’t slam into the lower box. The technicians calculated that they would amputate the top box of the bomb from the bottom box in .5 millisecond, cutting the trigger wires before an electrical charge could pass through to the explosives below.24

According to one account, Birges placed a couple of sticks of dynamite in the top box to wipe out any fingerprints he may have left behind while building the bomb. As a result, when the shaped charge was exploded at 3:43 that afternoon, the cumulative blast triggered the trembler switches and detonated the dynamite in the main box. (Nelson recalls that the firemen put the charge in backward.) In any case, the bomb exploded “with a thunderous blast . . . sending thick gray smoke streaming through the casino district and causing heavy damage to Harvey’s.” The explosion sent pieces of glass, concrete, and the casino’s neon sign flying across the border into California, although that was only four blocks away.25

A security guard at the nearby Sahara Tahoe Hotel told the New York Times that the “whole front went out.” The detonation gutted the second and third floors, blew out windows, and collapsed balconies. The damage came to $12 million.26

Once the bomb had gone off, the FBI’s full attention turned to finding out who was responsible and putting them behind bars. Harvey’s employees reported seeing the white van. Other witnesses came forward with memories of what they saw or might have seen that might be relevant to the investigation. Joseph Yablonsky, the FBI agent in charge of the investigation, told the press that an artist was compiling drawings of the three suspects—two men and a woman—with some of the descriptions provided as the result of hypnosis. Fingerprints were also reported to have been found on the bomb. In addition, the extortion letter was being studied, by NEST consultant Murray Miron among others, to produce a psychological profile of its author.27

In mid-September the FBI released sketches of two men, one said to be about five feet seven inches tall and twenty years old with sandy blond hair and a light mustache. The other was described as six feet tall, “a hayseed type with protruding ears,” and in his mid twenties. A little over a year later, in September 1981, after a tip from the boyfriend of a girl whom John Jr. had broken up with, the two brothers would be in court pleading guilty. They had agreed to testify against their father, reportedly in retaliation for the beatings they had received in earlier years and his treatment of their mother, who had committed suicide in 1975. As a result they escaped time in prison.28

Their father did not. On the stand Birges claimed that a man named “Charlie” warned him that if he didn’t bomb the hotel, he would cripple him. He further implied that the mastermind behind it all was Harvey Gross, who allegedly wanted to use the insurance money to renovate his hotel. He also apportioned some of the blame to his dead ex-wife for having given him $2,000 to gamble. It was a ploy to get him out of the house, he explained, so she could have sex with other men. The jury wasn’t convinced, and Birges spent the rest of his days behind bars, dying from liver cancer in 1996 at the Southern Nevada Correctional Center. His girlfriend, Ella Joan Williams, was also convicted, but her conviction was overturned in 1984.29

Almost all the damage that Birges’s bomb did was long ago swept up and either disposed of or used in the FBI’s investigation. But a piece of bent aluminum from one of Harvey’s windows is on a plaque in William Nelson’s home office, near Livermore. The inscription on the plaque is “win some, lose some.” This case was not a complete loss though. NEST did learn about how sophisticated homemade bombs could be, and about the booby traps one might contain. Nelson recalls that knowledge would have an impact on the program. It also led to an agreement between NEST and the FBI and the management of the national laboratories on how to respond to non-nuclear bomb threats.30

In 1981 there were three incidents. On January 9, Reno, Nevada, was threatened with plutonium dispersal. Seventeen days later, San Francisco was the target of a threat involving an alleged atomic device. On June 25, San Francisco was threatened again, but with even greater devastation. This time someone claimed to have a thermonuclear bomb ready to detonate in the city. A one-megaton device would level the city from downtown to Fisherman’s Warf.31

On April 10, 1982, President Ronald Reagan signed National Security Decision Directive (NSDD) 30, titled “Managing Terrorist Incidents.” Among its key provisions was its designation of the “lead agency”—the agency with the most direct operational role—in dealing with terrorist incidents. The Federal Aviation Administration was named the lead agency for “highjackings within the special jurisdiction of the United States,” while the Department of Justice was to take the lead for terrorist incidents within U.S. territory. But for international terrorist events, the State Department was to take charge.32

The directive was not very specific about the types of terrorist incidents that could occur, or what the State Department would do in the event of an international terrorist incident. A month later, Richard L. Wagner, the veteran of Morning Light who was representing the Department of Defense, signed a memorandum of understanding, originally completed in January, that had already been signed by representatives of the State and Energy departments. With Wagner’s signature, the memo took effect. It specified the role of the State as well as the Energy and Defense departments with regard to “malevolent nuclear incidents” outside the territory or possessions of the United States.33

By the time that memo was signed though, there had already been nuclear threats to several foreign nations, threats apparently conveyed to one or another component of the U.S. government and analyzed by the credibility assessment group at Livermore. On March 16, 1975, in addition to Washington, D.C., Beijing and Moscow were threatened with atomic destruction. During the first week of 1980, about two months after the U.S. embassy and staff in Tehran had been seized, Tehran was the target of a nuclear threat—the biggest and most implausible ever made, since it involved three 20- to 25-megaton bombs.34 Of course, neither China, the Soviet Union, nor Iran was likely to ask for U.S. assistance in evaluating the credibility of a threat or locating a nuclear device hidden on their territory. But one day, a nation with closer ties might ask for just such assistance or the United States might offer it unsolicited.

In such an instance, the State Department’s responsibilities would include obtaining the approvals necessary for U.S. aid, contacting other federal agencies, and requesting assistance from the Energy and Defense departments. Of course, many of the references to “Energy” in the memorandum were references to NEST. Thus, “Energy” would be expected to provide “scientific and technical support for assessment, search operations, identification, diagnostics, device access and deactivation, damage limitation,” and so on—exactly what NEST would be asked to do for domestic malevolent nuclear incidents. In such an event, the State Department was required to provide NEST with exact copies of any threat messages, drawings, and other relevant intelligence as well “as all available information pertinent to an assessment of a threat perpetrator’s technical capabilities to carry out a threat.”35 Thus, one day NEST personnel might find themselves boarding a plane to Ottawa, Sydney, Tokyo, Tel Aviv, or elsewhere in response to a credible threat to unleash atomic destruction.

While the memo concerned hypothetical nuclear threats, in 1982 there were real threats to a number of U.S. cities—“real” in the sense that someone communicated a threat by phone or letter. On May 16, twelve unidentified U.S. cities were threatened with nuclear warheads. On June 14, in a case of déjà vu, Boston was threatened with a nuclear detonation. Less than a month later, in very early July, Washington, D.C., was threatened with a radioactive device. The year’s threats concluded with two in October, on the other side of the country: Las Vegas on October 8 and Los Angeles on October 19. While Las Vegas faced only a ten-kiloton device, Los Angeles faced a thermonuclear detonation, according to the threatener. But, as usual, all the threats proved to be empty.36

Between the beginning of 1980 and the end of 1982, two significant exercises were carried out. The first one, Sundog, took place in the desert near Stallion Gate, the northern entrance to the White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico. In addition to the Delta special operations unit, this full field exercise involved NEST and included a “tactical air insertion of NEST assets.” It also entailed an assault on terrorist forces by Delta personnel, with the work of diagnosing and disabling a simulated nuclear device assigned to NEST personnel.37

The second exercise, designated Prince Sky, also involved NEST and Delta and took place not on some remote facility in the desert but in downtown Los Angeles. Local law enforcement participated, and, Chambers recalls, the exercise “was carried out without public or media attention.”38

At the very end of 1982, the State Department announced that NEST had been placed on alert, and it looked like NEST personnel might well be headed for some foreign business travel. But it wouldn’t be the result of any threat to detonate a nuclear weapon. Rather, the Soviet Union was having trouble with yet another of its nuclear-powered ocean surveillance satellites. This time it was Cosmos 1402, which was forty-six feet long, weighed 11,000 pounds, and had a thirty-foot radar antenna, and a nuclear reactor located in the satellite’s twenty-three-foot rear section.39

The problem with Cosmos 954 did not prevent eventual resumption of the Soviet Union’s RORSAT program. Launch activities resumed in late April 1980 with Cosmos 1176. In 1981, three of the nuclear-powered satellites were orbited. And in May and June 1982, RORSAT’s Cosmos 1365 and Cosmos 1372 were launched from Plesetsk to monitor naval developments during the short Falklands War between Britain and Argentina. They were followed by Cosmos 1402.40

Like Cosmos 954, Cosmos 1402 orbited at an inclination of 65 degrees, so that in the course of its revolutions around the earth it passed over all points between 65 degrees north latitude and 65 degrees south latitude, and thus could come down anywhere in between the Arctic and Antarctic circles. All the land in the Southern Hemisphere and the land in the Northern Hemisphere up to mid-Alaska and Scandinavia were included in that range. But almost 70 percent of what was under Cosmos 1402 was water.41

After it was launched in August 1982, Cosmos 1402 began orbiting at a maximum altitude (its apogee) of 173 miles and a minimum altitude (its perigee) of 157 miles. The satellite apparently operated normally until December 28. By early January 1983, the satellite trackers at the North American Aerospace Defense Command were tracking two objects associated with Cosmos 1402—the satellite with its reactor, and a fragment—and reporting that the satellite’s orbit had dipped to an apogee of 153 miles and a perigee of 145 miles. In addition to reporting that it was losing altitude, NORAD was telling its customers that the satellite was behaving erratically. Department of Defense analysts reportedly suspected a rocket-system malfunction, a faulty separation of satellite and reactor, or some combination of those problems.42

Rather than try to keep the possible demise of the Soviet spy satellite a secret, as with Cosmos 954, the Defense Department issued a statement revealing the apparent malfunction and predicting a probable return to earth in late January. Soviet spokesmen, at least initially, claimed that nothing was wrong. At a Moscow news conference, Vladimir A. Kotelnikov, a vice president of the Soviet Academy of Sciences, claimed that the changes in the satellite’s orbit were part of a “preplanned operation” and that “we have no worries about the fate of this Sputnik.”43

Some space experts suggested that such claims might mean that Moscow believed it would be able to command the satellite to lift its orbit to a higher, safer altitude or it would be able to guide the satellite’s reentry into the earth’s atmosphere so that any surviving fragments would fall into a remote ocean area. But Kotelnikov’s comments were not enough to convince the Defense and State departments that they were worrying needlessly. Spokesman Benjamin Welles responded, “We have no way of knowing if the Soviets have it under control. We hope so.” State Department spokesman John Hughes was even more skeptical, telling reporters, “Our information is different, and we want to talk about that with them, and, of course, we want to make known our concern.”44

In the meantime, NEST was placed on alert, in case it was needed anywhere in the United States. State Department spokesman Hughes also told the press that the United States was offering NEST’s services to other nations that might be hit with debris. Ira Morrison, a veteran of Operation Morning Light, carried a pager, as did all other NEST members, so that he could be called into action without delay. Morrison, whose day job was as a computer analyst with Lawrence Livermore’s Z Division, which analyzed sensitive intelligence about foreign nuclear weapons programs, was skeptical that the team would get any help from the Soviets. He recalled, while waiting for the Soviet satellite to come down to earth, that when Cosmos 954 was in trouble in 1978, “they really didn’t tell us anything that was useful.”45

In addition to placing people on alert, the Energy Department, around January 18, began loading three C-141 Starlifter cargo planes with equipment for NEST operations, including lead-lined containers for storing radioactive debris and the same type of equipment used in Operation Morning Light to detect radioactive satellite fragments from the air.46

By the time NEST had begun loading equipment onto the C-141s, the Soviet Union had acknowledged that all was not as it should be with Cosmos 1402. On January 15, Oleg M. Belotserkovsky, the longtime rector of the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology, often referred to as the “Russian M.I.T.,” spoke on Soviet national television for ten minutes. Belotserkovsky, an expert in mathematics and mechanics, told his audience that the satellite’s fuel core would reenter the earth’s atmosphere in mid-February, burn up, and be dispersed into “finely divided particles.” Any fallout, he reassured his listeners, would pose no health risks. He also acknowledged, unlike previous Soviet spokesmen, that the reactor and spent nuclear fuel should have been boosted to a higher, longer-lasting orbit.47

American experts were skeptical of Belotserkovsky’s claims that there were no health risks associated with the level of radioactive fallout expected from the satellite’s reentry. The State Department also questioned his prediction of a mid-February reentry for the fuel core. A spokeswoman said she had no reason to question earlier U.S. predictions that both the satellite and the reactor of Cosmos 1402 would return to earth in late January.48

Those predictions proved accurate, for at 5:21 p.m. Eastern Standard Time on January 24—almost exactly five years after Cosmos 954 reentered the earth’s atmosphere—Cosmos 1402 returned to earth. Members of the American military, serving on Diego Garcia, saw the burning satellite for forty seconds as it cut across the sky, while astronomers at the Royal Greenwich Observatory near London saw an object that looked like “a bright fast-moving star.” In contrast to 1978, the latest wayward Soviet spy satellite fell, without incident, into the Indian Ocean, in a part of the ocean far south of the Indian subcontinent and far west of Australia, where there was not even an island on which to scatter debris.49

The United States alerted facilities, including stations operated by the Air Force Technical Applications Center, used to monitor nuclear fallout to check for any increase in atmospheric radiation due to the satellite reentry. In addition, U.S. aircraft and ships patrolled the Indian Ocean, looking for any signs of radiation. Meanwhile, U.S. space trackers continued to watch the fragment of Cosmos 1402, weighing less than 1,000 pounds, that had remained in orbit.50

That fragment was the fuel core, which, on January 24, the Soviet space monitoring organization predicted would burn up in the atmosphere between February 3 and 8. At 6:10 a.m. on the morning of February 8, the final piece of Cosmos 1402 “vanished in a fiery plunge over the South Atlantic Ocean 1,100 miles east of Brazil.” According to a Pentagon spokesman, the 110-pound enriched-uranium core appeared to have “burned harmlessly.”51 On this occasion, the services of Ira Morrison and other members of NEST would not be needed.*

On February 2, about a week before the final piece of Cosmos 1402 reentered the atmosphere, the United States faced another nuclear threat, from someone claiming to have dispersed radioactive material in Tampa. Much later in the year, another threat occurred, and this one called for a significant federal response. At 2:00 a.m. on an October morning in 1983, the FBI’s new Hostage Rescue Team (HRT)—fifty agents who had been chosen out of the bureau’s pool of investigators—and a local SWAT team snuck into position. A few days earlier, a terrorist group with a nuclear weapon had promised to destroy Albuquerque, New Mexico, home of many members of NEST, if its demands were not met. In response, an HRT advance team soon arrived, established a tactical operations center, and began collecting intelligence on the suspected group. Not long afterward, the main HRT arrived in a C-130, which also carried vehicles and weapons.52

While negotiations dragged on for several days, the FBI believed it had located the nuclear weapons. A NEST helicopter, with a gamma-ray sensor, provided the confirmation. As the FBI suspected, the bomb was hidden in a building in downtown Albuquerque. The terrorists were hiding in a different location, not far away. Earlier surveillance work identified the terrorists and revealed all the booby traps at the terrorist hideout. Meanwhile, in the desert outside the city, the HRT constructed a duplicate of the hideaway and practiced for a possible raid.53

That night the HRT clandestinely approached the terrorist facility, while the local SWAT team gathered outside the building containing the nuclear weapon. The two commando units had arranged for a simultaneous attack. The terrorists had a remote detonator, but the FBI rescue team planned to block the terrorists’ signal by electronic jamming. Members of the HRT placed charges in two different locations and stormed the building, throwing flashbangs as they entered. Within thirty seconds, the terrorists were dead, and Albuquerque was still standing. NEST’s work had allowed the FBI and SWAT team to conduct the raid with confidence that they had located the nuclear device. Of course, it was only an exercise—one designated Equus Red.54

That exercise was “the first and last time,” according to William Chambers, that a major urban search was attempted employing local emergency service personnel who were recruited and trained in the midst of the exercise. The difficulty of turning firemen and paramedics into a NEST auxilliary force on the fly proved too much, leading to the idea of a periodically trained group of reserve searchers.55

The multitude of nuclear threats in 1984 did not appear to produce NEST deployments—but threats there were. In February, Hill Air Force Base in Utah was threatened with an atomic bomb. In October, Detroit was the target, and the instrument of destruction was a nuclear device. On November 7, as the nation went to the polls to choose between presidential candidates Ronald Reagan and Walter Mondale, someone claimed to have hidden a hydrogen bomb at an unspecified location. Then, nine days later, Fairfax County, Virginia, was threatened with a “small nuclear device.”56

There were also two threats to targets in California that year. On July 29 someone claimed to have a nuclear device and a willingness to detonate it in Covina. The following day, Los Angeles was threatened yet again, with an atomic bomb, but this time the city was in the midst of hosting the 1984 Summer Olympics—which the Soviet Union and thirteen other Eastern Bloc nations were boycotting in retaliation for the U.S. boycott of the 1980 Olympics in Moscow, a maneuver that meant more gold medals for the United States. President Reagan had mandated security preparations for the Olympics by his approval of NSDD 135, “Counterintelligence and Security Precautions for the Summer Olympic Games,” on March 30, 1984. Whether the directive directed a NEST deployment as a precaution is not clear, since almost all of the top-secret directive had been redacted prior to its public release.57

According to William Chambers, NEST did deploy to Los Angeles as a precaution, part of what would become ongoing cooperation with the FBI in dealing with what would years later be designated a National Special Security Event (NSSE).58

In the first four months of 1985 there were two threats. On March 14, Chicago was threatened with a five-kiloton bomb. Then, in April, a small contingent of NEST personnel descended on New York, the catalyst for their journey, strangely, being a subway shooting that had taken place late the previous year. On December 22, 1984, four young African-American men boarded a downtown No. 2 express train intent on stealing money from video arcade machines in Manhattan. It was their bad luck that Bernhard Goetz entered the same subway car at the 14th Street station and took a seat nearby. Almost immediately, one of the four, Troy Canty, age nineteen, told Goetz to give him five dollars, a demand that he repeated when Goetz asked him, “What did you say?”59

Goetz, who had turned twenty-seven the month before, held a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering from New York University and had already been mugged twice. In a moment similar to what millions had viewed in movie theaters when they attended screenings of the 1978 Charles Bronson film Death Wish, Goetz stood and fast-drew a .38 caliber Smith & Wesson and emptied its five-shot load into Canty and his three friends. Goetz would later tell the police that he had “snapped” and that his intention was to “murder them.”60

All four survived, but only because Goetz ran out of bullets. As a result Goetz was tried for attempted murder and assault, rather than murder. But while some considered him a racist, others considered him both a vigilante and a hero. His act came at a time when New York reported a crime rate that was 70 percent higher than the rest of the country. On an average day, the subways hosted thirty-eight crimes.61 And at least one or more of his admirers did not plan to sit idly by and wait to see how a jury of Goetz’s peers would judge him.

On April 4, 1985, while Goetz was still awaiting trial, Mayor Edward Koch received a hand-printed letter. It began, “unless all charges against berhard goetz [sic] are dismissed by 1700 hours, 11 april—and totally dismissed—a substantial quantity of plutonium trichloride . . . will be introduced at several locations into the water supply of new york city.” The writer also warned the mayor not to make the contents of the note public.62

The NEST team that arrived in New York shortly after Koch received the letter was part of a two-fold NEST response to the threat. Back at Livermore, analysts with the credibility assessment program examined the brief letter both to judge its technical accuracy and to search for any clues it might yield about the author’s willingness to carry out the threat. Meanwhile, the small contingent would check the water in New York’s reservoirs up to April 11 for any sign that it had been contaminated, and would survey areas in the city at four-hour intervals for signs of radioactivity.63

At first the team found nothing dangerous. Tests of the water indicated plutonium levels of 0.1 to 0.6 femtocurie per liter.* Tests on April 17 showed levels of 21 femtocuries per liter in a single sample—still well below the federal guidelines of 5,000 femtocuries per liter as the maximum level of plutonium safe for drinking water. The tests could not determine whether the plutonium had been introduced as part of a trichloride compound or had come from another source, but experts did rule out nuclear power plants or the fallout from atmospheric nuclear tests as causes. They could not rule out the possibility that the containers used to hold the water samples were contaminated with plutonium.64

Another incident occurred before the year was out. On November 22, someone claimed to have hidden three nuclear devices in Albuquerque. It is not known whether the threat was considered sufficiently credible to result in a deployment of NEST personnel.65

William Chambers recalls that in 1986 NEST “took an inward look at its progress over the prior decade through an independent review panel and found some reasons for both pride and despair.”66

In early December 1986 a large group of NEST personnel arrived at Camp Atterbury, Indiana. It was the base Chambers had traveled to be discharged from the military at the end of World War II. But the NEST contingent was there for an exercise that they certainly hoped would alleviate some of the despair. By that time there had been six nuclear threats for the year. In April, it was New York and Murmansk (atomic devices); in May, Reno (nuclear device); in September, Wisconsin (nuclear device); in October, Westminster, California (thermonuclear device), and Concord, California (six-megaton device); and in November, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania (americium-241 dispersal).67

Construction on the camp had begun shortly after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. During the war it was home to a number of Army divisions; the Wakeman General and Convalescent Hospital, the largest of its kind in the United States during the 1940s; and a prisoner-of-war camp for German and Italian soldiers. The Indiana National Guard established an air-to-ground gunnery range in 1958. The camp stretched about seven miles wide and twelve miles from north to south. Members of NEST were there for an exercise designated “Mighty Derringer.” The Pentagon—which sponsored the exercise—had generated the name, and, whether intentional or not, it was appropriate for an exercise concerning nuclear terrorism, since it conjured up an image of a small device with a deadly impact.68

While Camp Atterbury was the local command post for Mighty Derringer, the city of Indianapolis was the main site of the exercise, nuclear sources having been deposited in several locations. One objective was to determine if NEST could deploy, get to a target city, do its search, and detect hidden nuclear weapons.69

A more important objective was testing the ability of the multiple organizations involved in managing a nuclear extortion or terrorist incident to work together, including the FBI’s Hostage Rescue Team and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). The exercise was, according to former NEST official Alan Mode, “really, really big” with “all of the agencies and organizations involved” so that “hundreds and hundreds of people” participated.70

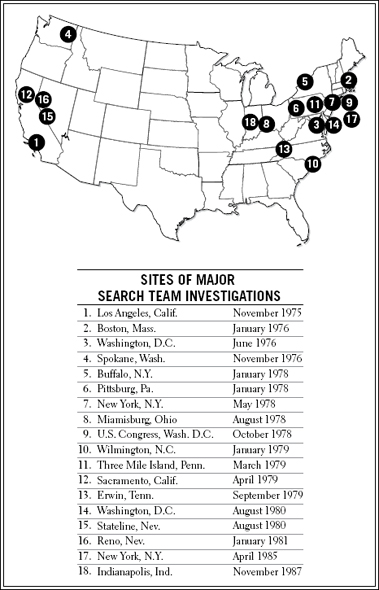

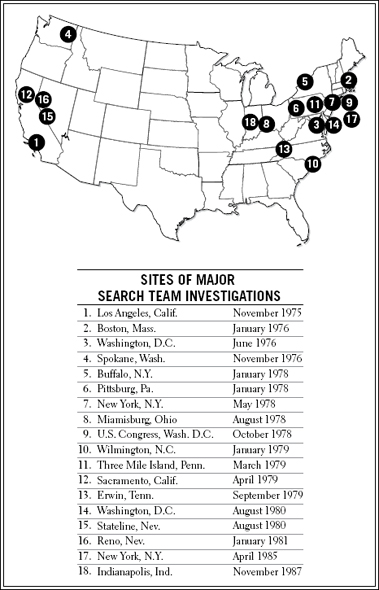

NEST Deployments 1975–1989 (Source: Judith Valente, “Secretive Federal Program Combats Terrorism,” Washington Post, June 21, 1983)

Part of the exercise also took place at the Nevada Test Site, where it was possible to “have real explosions,” according to former NEST official William Nelson. Participating along with NEST personnel were members of the Defense Department special operations forces.71

The exercise attracted high-level interest and involved high-level players. The State Department directed it from its Operations Center in Washington. William Nelson stressed its value in getting people and organizations, including the CIA and FBI, together so that if there was a real incident, they would have experience working together. But Alan Mode noted that NEST had some “difficulty with the exercise” and that it was too big, that everyone wanted to participate, and everyone wanted to use their “own gadget.”72 It was a problem that would recur a decade later.

In 1987 NEST returned to Indianapolis, although in much smaller numbers. And this time it was not an exercise. On November 27, a telephone caller made two claims: first, that he represented a Cuban political movement and second, that a nuclear device he had produced would detonate that night inside a bank building. NEST searched but found nothing.73

And, as might be expected, the threateners were not through for the decade. In June 1988 they claimed to have atom bombs in Washington, D.C., and Moscow. In January 1989, someone or some group claimed to have three nuclear bombs “somewhere in the USA,” and in April, Washington, D.C., was threatened yet again with another, apparently imaginary, atomic bomb.74

*Cosmos 1402 would not be the last encounter with a troubled Soviet nuclear-powered ocean surveillance satellite. In 1988, the Soviets lost control over Cosmos 1700 but were able to fire its reactor into a safe orbit. See William Harwood, “Crippled Soviet Satellite Fires Reactor into ‘Graveyard Orbit,’ ” Washington Post, October 2, 1988, p. A6.

*A femtocurie is one-millionth of one-billionth of a curie (Ci), where Ci = 3.7 × 1010 decays per second.