FORMER DIRECTOR of central intelligence George Tenet recalls that on December 3, 1998, he sat at home “and furiously drafted in longhand the memo . . . titled ‘We Are at War’ ” and told his staff that he “wanted no resources or people spared” in the effort to attack Al-Qaeda.1 That was one indication within the U.S. Intelligence Community of the growing attention to the terrorist organization.

Before and after that time, NEST continued to conduct exercises against a variety of possible threats as well as deploy in response to the occasional plausible threat. In addition, a directive signed by President Bill Clinton would establish a class of events that seemed to mandate precautionary deployments by a wide array of U.S. law enforcement and counterterrorist units—from the FBI and Secret Service to those consisting of scientists with radiation detection equipment or secret soldiers equipped with a variety of lethal weaponry.

On May 22, 1998, Clinton resorted to a measure he used sparingly during his administration—he signed a presidential decision directive. In contrast to his most recent two-term predecessor, Ronald Reagan, who signed more than 325 national security decision directives during his eight years in office, Clinton would only issue seventy-five. The one he signed that day, a few months into the sixth year of his presidency, was PDD 62, “Protection Against Unconventional Threats to the Homeland and Americans Overseas,” and the fifth that concerned nonproliferation or terrorism.2

The directive noted “that the destructive power available to terrorists is greater than ever. Adversaries may thus be tempted to use unconventional tools, such as weapons of mass destruction to target our cities and disrupt the operations of our government.” It also continued the practice of designating the State Department, FBI, and other agencies as the “lead” agencies in responding to certain types of terrorist events. In addition, the directive established a special class of events, designated National Special Security Events (NSSEs). The designation followed nomination by the National Security Council and certification by the attorney general and secretary of the treasury. An event could qualify as an NSSE based on at least one of several factors: anticipated attendance by U.S. officials or foreign dignitaries, its size, or its significance.3*

Senior officials believed such events warranted greater federal planning and protection than other special events, for the obvious reason that they were judged to be very attractive targets to terrorists. A successful attack would either kill a lot of people or kill some very important people, or both. The first national special security event would be the mid-September 1998 meeting of the World Energy Council in Houston, an event attended by more than eighty oil ministers and eight thousand officials and executives from at least eighty-two nations who were there to celebrate the council’s seventy-fifth anniversary as well as bemoan falling oil prices. By early February 2007 there had been twenty-seven special events, including a variety of international meetings, national political conventions, inaugurations and state of union addresses, the 2002 Winter Olympic Games in Salt Lake City, and six Super Bowls.4 One result of the creation of this new category of events was more work for NEST.

In the mid-1990s, before the signing of PDD 62, NEST personnel continued to participate in a variety of exercises, such as Mirrored Image in Atlanta in 1996 (which involved an improvised nuclear device), Jagged Wind in June 1996, Ellipse Charlie in September 1996, Action Warrior in December 1996, Patriot Pledge in January 1997, Patriot Finance in June 1997, Ellipse Foxtrot in June 1997, and Bright Victory in March 1998.5

The first post–PDD 62 exercise was Gauged Strength in June 1998. That was followed by Package Satyr, conducted between August 4 and 6 at Pease Air National Guard Base in Newington, New Hampshire. It involved seventy-five participants from the Justice, State, Defense, and Energy departments, with fifty-two from Energy. The exercise tested the ability of NEST and other government personnel who made up the Foreign Emergency Support Team (FEST) to promptly assemble and be deployed on a dedicated FEST aircraft to a “foreign” country, where they would assist the host government in searching for and locating missing special nuclear material.6

At the end of August, another exercise, Errant Foe, began. It kept some of NEST’s members busy from Saturday, August 29, to Wednesday, September 9. As with Package Satyr, NEST personnel, among the thirty-seven Energy Department members who participated, were engaged in an exercise that took place in a “foreign” locale, and it involved representatives of the U.S. Special Forces, probably Delta Force, and the Army Forces Command’s 52nd Ordnance Detachment.7

After participating in Lost Beacon in July 1999, NEST personnel could be found in Pennsylvania in September for yet another exercise—this one designated Vigilant Lion. The event was sponsored by the Pennsylvania Emergency Management Agency, in cooperation with the Energy Department. It was no small event, involving more than three hundred participants from forty local, state, and federal emergency response agencies whose missions included managing hazardous materials, explosive ordnance, emergency management, law enforcement, and emergency medical response.8

Initially, some of those agencies favored conducting the exercise in Hershey, an area with a population of nineteen thousand, with the state police academy and a major hospital nearby. But getting the necessary approvals would have proved difficult, and it was believed that a large-scale realistic exercise in public would have produced significant public concern, if not alarm. Instead, it was decided to approach the Fort Indiantown Gap Military Reservation, home of the Pennsylvania National Guard Civil Support Detachment, whose leadership agreed to host the exercise.9

The exercise began on the evening of September 27, when a disgruntled former employee placed a radiation dispersal device on the intake vent of the two-story “Fig County office building” (a vacant structure), where approximately 550 county and city employees worked. With a small fan connected to a timer, the device “spread” strontium-90, which is absorbed by the body as if it were calcium and can produce bone cancer, throughout the building. By the end of September 28, a multitude of federal and state agencies were on the scene: the Pennsylvania National Guard Civil Support Detachment, the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection, the FBI, and several Department of Energy organizations, including the Aerial Measurement System (AMS) and NEST.10

The FBI and AMS proved able to locate additional radiological substances in a residential area. But NEST’s more sensitive equipment proved vital in finding the precise location: a rundown two-story residence on Lazy Eye street. A vehicle-based search was used to identify the specific house, where the former employee resided. In a follow-on search on foot, NEST equipment detected high levels of radiation from material outside the house. Local, state, and federal law enforcement officials then raided the home, discovering additional conventional explosive devices inside, along with guides for building further bombs. NEST personnel also determined that there was a second radiological dispersal device in the dwelling with a two-hour timer that had been activated.11

In April 2001, NEST personnel were involved in an exercise designated Wasatch Rings, sponsored by the FBI and Utah Olympic Public Safety Command with a future national special security event in mind—the 2002 Olympic Winter Games in Salt Lake City. Despite the growing concern with Al-Qaeda and foreign terrorist groups, the exercise, staged at various Winter Olympic sites, revolved around a fictional radical domestic terrorist group. Scenarios included a plot to detonate an improvised explosive device during the games, an overland manhunt, a kidnapping incident, a hostage barricade situation, the detonation of a radiation-laced bomb, a train derailment that involved hazardous materials, and interception of an aircraft suspected of carrying radiological material by an FBI SWAT team (after it was identified, presumably by NEST sensors).12

NEST participation in the exercises came in a variety of forms, as the group’s varied responsibilities were divided among a number of different teams. Indeed, by the late 1990s NEST had become almost an umbrella term, particularly because some NEST elements had been established as a result of closer links between NEST and the military, particularly the secret warriors of the Joint Special Operations Command.

Some members from NEST might arrive in the form of an eight-man Nuclear/Radiological Advisory Team (NRAT), which supervises the activities of all Energy Department personnel deployed during an incident, and is prepared to gather nuclear/radiological data and provide technical advice and recommendations to the “Lead Federal Agency”—the FBI in domestic incidents and the State Department for foreign incidents. It also serves as the Department of Energy portion of the interagency advisory team, the Domestic Emergency Support Team (DEST).13

The two components of NEST most associated with the team—because they constitute the “S” activity—are those involved in actual search operations, employing handheld and vehicle-mounted detection equipment. The Search Response Team will be first on the scene in response to a nuclear threat. The seven-member team, whose members are on two-hour recall, provides a quick response and may arrive on commercial aircraft. Once it arrives, it can be set up and ready to go in three hours. It can also equip and train local personnel to become searchers.14

A larger contingent of searchers, thirty-one scientists and technicians, make up the Search Augmentation Team, which can be on site in twelve hours. The size of the group as well as the technical capability they bring with them, allows for a sustained, fully equipped search effort of larger areas. Both teams are based at the Remote Sensing Laboratory.15

Two additional teams made up of NEST personnel go into action when the searchers have located a nuclear device. The Joint Technical Operations Team (JTOT) supports Defense Department and FBI explosive ordnance personnel, possibly operating in a “non-permissive or hostile” environment. The team, consisting of twenty-one Energy Department and ten Defense Department representatives, provides the advanced technical capabilities needed to move or neutralize nuclear weapons. The team’s activities include reducing the yield of the device, rendering the device explosively and electrically safe, as well as performing demilitarization and disassembly operations needed to make the device nuclear safe—missions complicated by a lack of immediate knowledge of the design of an improvised nuclear device. As a result, the team’s first task is to determine how the weapon was put together and its capabilities, and its members include experts in developing, testing, and evaluating the tools crucial for that task. It all adds up to a “stimulating mental challenge,” according to one Los Alamos scientist.16

A JTOT deployment has two phases. During JTOT-1, personnel provide technical advice to Defense Department explosive ordnance disposal personnel to help them render safe a nuclear device. During JTOT-2 a joint NEST/Defense EOD team prepares the weapon for safe transport for final disposition.17

In addition to those working in the field, a JTOT home team—consisting of Los Alamos and Energy Department volunteers—provides the teams with access to additional experts who can respond to requirements from the teams in the field. At the site, JTOT members, using their laptop computers and stored data on more than a thousand U.S. nuclear tests, can run simulations of a device’s destructive capabilities. If more extensive simulations are required, they can transmit information back to the home team, which has access to the lab’s entire computing capability.18

If explosive ordnance personnel from Defense Department special mission units—such as Delta Force or the Naval Special Warfare Development Group (formerly Seal Team 6)—get involved, NEST personnel, acting as a five-man Lincoln Gold Augmentation Team (LGAT), can provide assistance. The augmentation team can provide advice concerning diagnostics, render-safe procedures, weapons analysis, device modeling, and effects prediction. Back at the labs, like the JTOT, the team is supported by a “home team”—in this case, the Lincoln Gold Home Team.19

In addition, the members of the Nuclear Assessment Program (NAP) may have been called upon to participate in various exercises in addition to responding to external nuclear threats. The director of the Lawrence Livermore laboratory described the members of the program as consisting of “a small group of professionals who are collectively knowledgeable in nuclear explosives design and fabrication, nuclear reactor operations and safeguards, radioactive materials and hazards, linguistic analysis, behavioral analysis and profiling, as well as terrorist tactics and operations.” He explained that assessor teams were organized into specialty teams and “operate in secure facilities” at three sites. The Assessment Coordinating Center at Livermore directs credibility assessment operations for the Energy Department and “provides a single point of contact for federal crisis managers during . . . emergency operations.”20

Jagged Wind involved members from the Search Response Team, Search Augmentation Team, and Nuclear/Radiological Advisory Team. Personnel from the same three teams participated in Package Satyr. In Vigilant Lion representatives of the Search Response Team helped locate the nuclear material on Lazy Eye Street. In contrast, during the Errant Foe exercise in late August and early September 1998, representatives of the Search Response Team and the Search Augmentation Team were absent, while members of the Lincoln Gold Augmentation, Lincoln Gold Home Team, and the JTOT did participate.21

In the midst of all the exercises there was an occasional threat not invented by the Scenario Working Group. In 1998, NEST member Darwin Morgan received a page while he was at the movies with his wife. It was from NEST and directed him to stop whatever he was doing and come to the office. The team had just received a tip alleging that a nuclear device was hidden on a train that was rumbling across South Dakota. A Search Response Team, with its suitcase radiation detectors, rushed to the site—and found nothing, apparently having wasted their time and taxpayers’ money checking out a hoax.22

NEST faced another threat about two years later, in May 2000, although it came not from a nuclear terrorist or extortionist but from the superintendent of the Bandelier National Monument in New Mexico. Superintendent Roy Weaver decided to start a fire on May 4 because he believed the conditions were just right for the park’s annual brush burning, which is intended to prevent a potentially disastrous fire. But when the winds turned out to be higher than expected, gusting at over fifty miles an hour, and the humidity did not rise as much as hoped, the brush fire became a wildfire that burned out of control.23

Among the consequences were the destruction of more than two hundred houses in Los Alamos and the forced evacuation of 25,000 people. The laboratory suffered too: damages amounted to several hundred million dollars, eight thousand acres were burned, along with thirty-nine temporary structures including trailers and storage units.24 The fire also led to what was feared for a while to be a serious compromise of some of the data needed by NEST personnel to help prevent the detonation of an improvised nuclear device.

On May 7, with the fire raging, two NEST members at the Los Alamos lab entered the high-security vault of X Division, the lab component responsible for nuclear weapons design. What they were looking for were two computer hard drives, each approximately the size of a pack of cards, that were supposed to be inside locked containers in the vault. The containers were there, but the drives were not. The drives were to be used in laptops of NEST personnel and contained the U.S. nuclear weapons design data, as well as data on Russian nuclear testing, that NEST would use if it ever located an improvised nuclear device. Members would enter the available information into classified software on the drives and would receive, in return, suggestions on how to disarm the weapon. In the hands of terrorists, it would help them defeat NEST efforts to disable a bomb. A terrorist group could put “an extra wire, or an extra bump, or an extra piece of metal where there isn’t supposed to be one,” a Pentagon official observed. The missing data could also help terrorists bypass the internal safety system of a stolen weapon, intended to prevent an unauthorized detonation.25

Rather than report that the drives were missing, the NEST members kept the information to themselves, hoping they could locate them quickly and avoid a public relations fiasco or, even worse, a criminal investigation. They also hoped that possibly in the chaotic situation created by the fire, the hard drives might be in the hands of authorized personnel and would be returned when the emergency concluded. But when the fire ended, there was still no sign of them and a search began. When that produced no results, on May 31, more than three weeks after the initial discovery that they were missing, lab director John C. Browne was alerted. The next day both the the FBI and the Energy Department received the bad news.26

The feared public relations nightmare soon followed. The missing hard drives made front-page news as well as provided grist for politicians, cartoonists, comedians, and writers of letters to the editor. Bart Stupak, a member of the Michigan congressional delegation, complained that “the Menominee [Michigan] public library has a more sophisticated tracking system for ‘Winnie the Pooh’ than Los Alamos has for highly classified nuclear weapons data.” And the author of a letter to the New York Times complained, “I cannot enter the local bank and remove $20 from an automated teller machine without being taped,” yet “more than two dozen people have unfettered access to a vault that holds this country’s nuclear secrets.”27

The FBI arrived on June 5 at X Division to look for the hard drives, and the ensuing investigation created growing tension. There were a number of NEST members to investigate, as eighty-six members of the team had access to the X Division vault. For twenty-six, the control was less strict than at the local public library. They could enter without an escort and remove the hard drives without signing them out. The physicists at the lab did not embrace the FBI’s late-night interviews and polygraph tests, accusing the G-men of Gestapo tactics, a point of view occasionally delivered to the agents on site by a physicist who would stop and give the unamused agent a “Heil Hitler!” salute.28 Whether they also clicked their heels together for effect has gone unreported.

Before the end of the month, part of the mystery would be solved. To the great relief of NEST and other government officials, the hard drives were not in the hands of a terrorist. Indeed, just as one Los Alamos employee discovered them missing, another discovered them behind an X Division copier on June 16. The discovery didn’t answer the question of how the drives had gotten from the vault to their temporary resting place behind the computer. And nobody was talking. In mid-January 2001 the Energy Department announced that the FBI had been unable to determine who was responsible for their disappearance.29

Energy Secretary Bill Richardson’s announcement also noted that the FBI had discovered no evidence that there was outside involvement in the disappearance of the hard drives or that the classified information on the drives had been compromised. He also informed the press that the FBI would be taking no further action and the matter was being turned over to the department’s Albuquerque Operations Office and the University of California (the contractor responsible for running the labs for the Energy Department).30

On September 10, 2001, elements of NEST were in the middle of another exercise, designated Jackal Cave, a U.S. Special Operations Command operation held at RAF Fairford, about one hundred miles west of London and forty miles south of Oxford, in the Cotswolds region of the United Kingdom—where John le Carré’s fictional spy George Smiley envisioned buying a cottage in which to spend his final years. The field had served as base for U.S. Air Force B-52s during the 1991 Gulf War as well as ones used to attack targets in Yugoslavia in 1999. U-2 spy planes flew from Fairford in 1995 as part of operations over Yugoslavia. It is also the only TransOceanic Abort Landing site in the United Kingdom for the NASA Space Shuttle.31

The entire exercise involved more than five hundred personnel, sixty-two aircraft, and 420 short tons of cargo. It was NEST’s first participation in an overseas exercise since 1998. Three NEST elements were involved: the Nuclear/Radiological Advisory Team, the Lincoln Gold Augmentation Team, and the Joint Technical Operations Team.32

The absence of representatives of the two search teams, the participation of LGAT and JTOT members, and the classification of the after-action report—Secret/Focal Point—indicate that the exercise also involved the CIA and a special missions unit such as Delta Force to kill terrorists and seize a mock nuclear device, which needed to be moved and/or disabled.* But on September 11, the European Command’s commander-in-chief cancelled the exercise. By September 15, all NEST and Energy Department members had arrived back in the United States, via military airlift.33

While NEST had been exercising against a hypothetical terrorist threat, a very real attack had occurred back home.

In the hour between 1:45 and 2:45 in the afternoon in England, probably in the midst of another day of the NEST exercise, the terrorist attacks of September 11 occurred. Al-Qaeda struck New York and Washington. It was only twenty seconds shy of 8:47 a.m. in New York when American Airlines Flight 11, which had taken off from Boston and was headed to Los Angeles, was flown into the World Trade Center’s North Tower. It was one of four planes hijacked by Al-Qaeda operatives that morning. When another hijacked aircraft, United Airlines Flight 175, also scheduled to fly from Boston to Los Angeles, crashed into the World Trade Center’s South Tower a few minutes after 9:00, it was clear that the United States was under attack.34

And there was more to come. American Airlines Flight 77, from Washington, D.C., to Los Angeles, had also been seized, probably between 8:51 and 8:54 a.m., a little over thirty minutes after takeoff. At 8:54, the plane made an unauthorized turn to the south, and shortly before 9:38 it slammed into the Pentagon. That left one plane, United Airlines Flight 93, which had departed Newark for San Francisco at 8:42. Within an hour it had been hijacked, and shortly before 10:00 a passenger revolt began. As a result, rather than smashing into Congress, the White House, or the CIA, all aboard died a few minutes later when the plane crashed into a field in Shanksville, Pennsylvania.35

The attacks would produce another “We Are at War” memo from Tenet, in which he told his employees, “We must all be passionate and driven—but not breathless. We must stay cool. We must keep our heads.”36 That advice certainly applied to people and agencies outside the CIA—and certainly to NEST.

By the time the Jackal Cave participants landed in the United States, NEST was in the midst of its first alert of a new era. Shortly after the attacks on New York and Washington, members of the team were “alerted they could potentially be called out [for duty] . . . so they were asked to be on standby,” according to Nevada Operations Office spokesman Kevin Rohrer. Indeed, one NEST member recalls, “I got my notification between the time the first tower fell and the second tower fell.” While there had been no specific nuclear threat, the alert was ordered as a precaution.37

NEST personnel had made it to New York, to the site where the World Trade Center towers had stood. At first, the NEST team was stranded in Las Vegas, but then it received clearance to fly its specially equipped plane to New York the next day. Officially, the team was searching for industrial radioactive sources and hot spots, fires under the rubble. It may also have been looking for evidence of a dirty bomb detonation.38

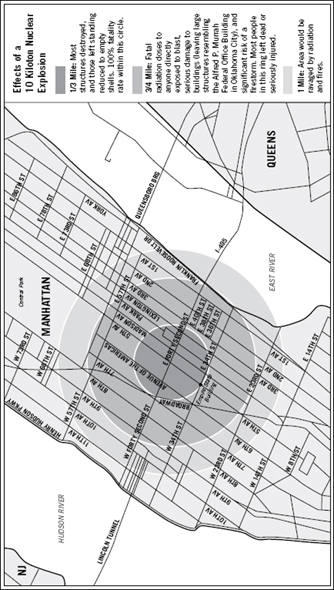

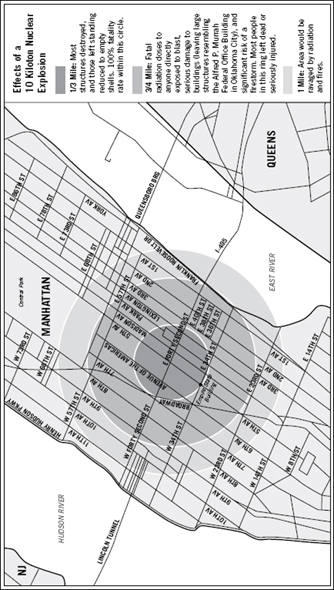

But the simple precautionary alert following 9/11 preceded what was feared to be a real threat. A Defense Intelligence Agency source code-named Dragonfire reported that a far more devastating attack might be in the works. His claims, which appeared in the Top Secret/Codeword Threat Matrix that was delivered to President George W. Bush on October 5, involved two frightening “mights.” Terrorists might have obtained a ten-kiloton nuclear weapon from the stockpile that survived the Soviet Union, and the device might be on its way to New York City. If it detonated at the intersection of Fifth Avenue and 42nd Street, it would destroy most buildings and kill every person within a third of a mile radius (from 34th Street to about 51st Street between Lexington Avenue and Seventh Avenue). Within three-quarters of a mile (stretching from 23rd Street to 59th Street between First and Ninth Avenues), people would be killed immediately or receive fatal radiation doses, and buildings would look like the Alfred P. Murrah building in Oklahoma City after the terrorist attack.39

The Threat Matrix questioned the credibility of the source, owing to errors in his reporting of technical details, and ultimately the report turned out to have no substance—the product of a U.S. citizen who claimed he had overhead some unidentified people discussing the possibility of a nuclear weapon in a Las Vegas casino. But it managed to “generate . . . weeks of terrifying uncertainty in the small circle of agencies that knew about it,” including director of central intelligence George Tenet and the White House Counterterrorism Security Group, according to Time magazine, partly because it was consistent with an intelligence report from a Russian general that his forces seemed to have lost a ten-kiloton weapon.40

Among those spared the terrifying uncertainty, in an effort to prevent a leak that might trigger mass panic among the city’s residents, were the mayor of New York, Rudolph Giuliani, his police commissioner and the rest of the New York Police Department, as well as senior FBI officials. After the media revealed the incident, Bernard Kerik, who was the police commissioner at the time, described the decision to withhold the information as “appalling.” Michael Bloomberg, Giuliani’s successor, commented, “I do believe that the New York City government should have been told.”41

Damage to New York City from Ten-Kiloton Weapon (Source: Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs/R7 Solutions)

By the time of Dragonfire’s warning, NEST was already engaged in precautionary operations. Members of NEST’s search teams were examining the readings of radiation detection equipment in helicopters hovering over New York City’s docks and bridges and over the Capitol and the White House in Washington. There is no certainty that they would have found a bomb had it been hidden below them. As one law enforcement official observed, “I don’t know how effective this would have been if there had been a bomb somewhere. You can’t search everything, and there are ways to shield nuclear materials from detectors. That fact is, we’re a wide-open society. We’re vulnerable. There’s only so much you can do, but you’ve got to do what you can.” As another official said about the effort, “But it’s better than having them sitting at home doing nothing.”42

After September 11, NEST precautionary patrols also drove around urban areas in vans known as “Hot Spot Mobile Labs” armed with instruments that detect alpha, beta, gamma, and neutron radiation. Other teams walked the streets equipped with backpacks holding smaller detectors. From the air, from roads, and on the street, NEST was conducting random weekly search missions focusing on ports, warehouse districts, and other sites where a smuggled nuclear weapon might be concealed.43

In January 2002, the administration ordered NEST to begin periodic searches for a “dirty bomb” in Washington and other large U.S. cities, even in the absence of a threat. Almost every week the FBI randomly selected several cities for sweeps by NEST. A team of six or fewer NEST scientists secretly prowled areas, such as docks in a coastal town, that local authorities considered most likely to have hidden contraband. Some NEST personnel operated in unmarked moving vans loaded with the sophisticated gamma and neutron detectors that are sensitive to the emission of radiation. Others traveled on foot with detectors concealed in briefcases, backpacks, or even beer coolers. In Manhattan, in October 2001, NEST personnel stood next to FBI agents and police, waving handheld detection equipment across thousands of trucks that were stopped and searched—looking for either a dirty bomb or Dragonfire’s ten-kiloton bomb. According to one law enforcement official, after the Dragonfire report, “we put a lot more hand-held detectors out on the streets.”44

The attacks prompted a number of other changes. The Energy Department put additional equipment in the field “so it’s much closer to the users,” Energy official John Gordon told a congressional committee, and created two more regional bases from which to operate. In 2005, NEST had twenty-nine teams in ten locations.45

NEST deployments in Washington, starting in late 2001, were part of a secret Bush administration initiative: the erection of a provisional defense against nuclear terrorism around the nation’s capital. Called the “Ring Around Washington,” its objective was to detect a nuclear or radiological bomb before the weapon could be detonated. The ring consisted of a grid of radiation sensors in the district and at major points of approach by river and road. It was still under development at the time of the 9/11 attacks, and not without its problems. Under some conditions the neutron and gamma-ray detectors failed to identify dangerous radiation signatures. In other conditions they raised false alarms over low-grade medical waste and the ordinary background emissions of stone monuments. But the attacks meant there was no time to wait—the system was pressed into service as a large-scale operational trial.46

Along with the Ring and the NEST-equipped vans patrolling Washington, a Joint Special Operations Command special missions unit, probably Delta Force, with personnel already trained to render safe a nuclear weapon or its components, moved to heightened alert at a staging area near the capital—possibly Fort Belvoir, which houses another secret JSOC unit, the Intelligence Support Activity.47

Washington was not the sole focus of increased U.S. nuclear detection efforts. Advanced detection sensors were deployed at U.S. borders and overseas facilities. They were deployed at the sites of national special security events, including the 2002 Winter Olympics in Utah—as were personnel from NEST. In addition, the detection equipment carried by Customs Service officers was upgraded to NEST standards. The geiger counters that were worn on belt clips and resembled pagers were replaced by devices—gamma-ray and neutron flux detectors—that previously had been carried only by NEST personnel.48

*Today, such events are designated by either the president or the Secretary of Homeland Security after consultation with the Homeland Security Council, an authority bestowed when President George W. Bush signed Homeland Security Presidential Directive (HSPD) 7, “Critical Infrastructure Identification, Prioritization, and Protection,” December 17, 2003, available at www.fas.org.

*The cover page to the after-action report indicates the document was classified Secret/Focal Point. Focal Point refers to “JCS information compartment dealing with CIA support to the military, special technical operations (STOs), and military-CIA operations.” See William Arkin, CODE NAMES: Deciphering US Military Plans, Programs, and Operations in the 9/11 World (Hanover, N.H.: Steerforth, 2005), p. 368.