ON OCCASION, threats against foreign cities or nations have been communicated directly to the U.S. government, including the threats against Tel Aviv, Moscow, and Murmansk mentioned earlier. But in other instances terrorists or extortionists have not bothered to “cc” the United States.

Between 1993 and 1995 alone, the German federal criminal police, the Bundeskriminalamt (BKA), recorded sixteen threats to spread radioactive materials for political or financial objectives. In one instance, an extortionist threatened to destroy four German cities by detonating “thermonuclear warheads” unless the State Lottery Administration paid him 100 million deutsche marks (about $62 million during that period). Then there was the letter signed “The Russian Mafia.” It demanded a mere 250,000 deutsche marks from a German casino and threatened to detonate a nuclear device in its neighborhood unless the casino paid up. In addition, a caller, who understandably declined to give his name, claimed there was a Serbian plan to launch a grenade filled with radioactive waste in Munich if German troops were deployed to Bosnia.1

A group calling itself the “German People’s Liberation Army” also issued a threat. The previously unheard-of group demanded that Poland evacuate former German territories that it had held since the end of World War I. Failure to comply, the liberation army warned, would result in Poland’s president and parliament being exposed to more than two pounds of plutonium allegedly concealed somewhere in Warsaw. In a fifth instance, an anonymous caller warned a German government department that six nuclear warheads were buried in eastern Germany, and offered, for one million deutsche marks, to reveal their location. In a second call he threatened to detonate one device by satellite. Eventually, the extortionist was identified and arrested in Italy. But he never went to trial, hanging himself while he was in detention.2

Subsequent to the arrest in Prague in December 1994 of a Czech nuclear scientist, a Russian, and a Belorussian—apparently while they were waiting in their car to meet a prospective buyer of the nuclear material in their possession—the investigating officer in the case received a threatening letter. The officer wasn’t the target of the threat but only the channel through which it was passed. The writer warned that unless the three were released, a small nuclear device would be detonated somewhere in Prague.3

In November 1995, a bit farther to the east of Germany, Shamil Basayev, leader of the Chechen separatists, threatened the population of Moscow with a radiological attack. Before being killed in July 2006, Basayev would direct the sieges of a Moscow theater in 2002 (which resulted in the death of more than a hundred hostages when Russian forces raided the theater) and a Beslan school in 2005, as well as the assassination of the Russian-backed Chechen president, Akhmad Kadyrov, also in 2005. But he first became well known in June 1995 when he led a raid against a hospital in Budennovsk, Russia, seizing the hospital and 1,600 people inside for several days. Before the siege ended, at least 129 civilians died and 415 were wounded in the fighting.4

In November, Basayev claimed that four radioactive packages had been smuggled into Russia, that at least two were hidden in Moscow, and that they could be detonated at any time he wished. To prove that the packages were not simply a figment of his imagination, the terrorist leader told Russian reporters where at least one parcel could be found. And a thirty-pound box containing radioactive cesium was found buried under the snow near the entrance to Izmailovsky Park, one of Moscow’s most popular recreation areas whose main attraction is Pokhorovoskiy Cathedral. Russian officials tried to reassure residents that there was nothing dangerous in the radioactive container, with one stating that “the first tests showed that beyond one meter from the package there was no threat to health. Initial tests show that the package does not pose a serious threat to the environment or health.”5

In March 2006, seven men were on trial in Britain, accused of having links to Al-Qaeda and plotting to carry out bomb attacks there. According to prosecuting attorney David Waters, one of those men, Salahuddin Amin, age thirty, had inquired about purchasing an atomic bomb from Russian Mafia figures in Belgium. Amin had allegedly been asked by a man he met at a mosque in Luton, his hometown, to contact another individual, Abu Annis, about a “radioisotope bomb.”6

More recently, in November 2006, British intelligence officials reportedly believed that Al-Qaeda was determined to detonate a nuclear weapon on British soil. At that time, Dhiren Barot, a senior Al-Qaeda member, was jailed for conspiring to kill hundreds of thousands of individuals in the United Kingdom and the United States. His plans included blowing up public buildings using gas cylinders in limousines, launching a gas attack on the Heathrow Express rail shuttle, and rupturing the walls under the Thames that keep the river from swamping the train that travels underneath. In the notebooks they seized, the police found details concerning the construction of a chemical laboratory, along with poison recipes as well as plans to use radiation to generate illness, panic, and death.7

Barot, a Hindu who had converted to Islam, had been communicating with Al-Qaeda about detonating a dirty bomb in Britain. Part of his research involved close examination of an unclassified report written by Charles Ferguson, a former nuclear submarine officer with training in physics. After leaving the Navy, Ferguson entered the world of security studies, coauthoring a book on nuclear terrorism while with the Center for Nonproliferation Studies in Monterey, California, and then becoming a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations. Ferguson’s report, Commercial Radioactive Sources: Surveying the Security Risks, appeared in 2003, and a printout with various portions highlighted was among the materials seized from Barot. Influenced by the report, Barot told Al-Qaeda that he was contemplating purchasing ten thousand smoke detectors, some of which contain small amounts of americium-241, as raw material for his bomb.8

Also occurring overseas are events—including athletic competitions—comparable to national special security events in the United States. In December 2001, in the wake of 9/11 and the recognition of the attractiveness of such events to terrorist groups, which had been demonstrated almost three decades earlier in Munich, the United States established an interagency committee, the International Athletic Events Security Coordination Group, chaired by a representative of the State Department. Members come from the Intelligence Community and several departments, including Defense, Energy, Justice, Homeland Security, and Health and Human Services. The group’s mission is to coordinate U.S. efforts in support of foreign government and U.S. embassy operations to protect international sporting events from terrorist attacks.9

The most prominent of international athletic events is, of course, the Olympics. The first post-9/11 Summer Olympics took place in Athens, Greece, starting on August 13, 2004. By the time of the closing ceremony on August 29, which was attended by 70,000 fans, 10,625 athletes from 202 nations had participated in 301 events in twenty-eight different sports. Also participating or attending were approximately 5,500 team officials, 45,000 volunteers, and 21,500 media, in addition to the huge number of people who showed up to watch the competition.10

The combination of explicit threats and attractive targets suggests an overseas role for NEST and other radiation-monitoring elements of the Department of Energy in searching for possible nuclear or radiological dispersal devices as well as assisting the nuclear detection efforts of foreign governments. Indeed, almost one week before the beginning of the Athens games, the State Department produced a document titled Strategic Plan for Interagency Coordination of U.S. Government Nuclear Detection Assistance Overseas, in cooperation with elements of the departments of Commerce, Defense, Energy, and Homeland Security.11

The plan envisions distributing four types of radiation detection equipment to a variety of nations. One type involves pedestrian, vehicle, and portal monitors. Another is handheld radiation detection devices, the kind that NEST members might use while covertly searching for nuclear material. Third are isotope identifiers. Also included is equipment needed to support the operation of portal monitors and collection of data from the detection efforts.12

The plan links distribution of the equipment to four goals, one being to permit nations receiving the equipment to possess a comprehensive capability to detect and intercept illicit special nuclear or radiological material. Two additional objectives focus on ensuring that the equipment would be used to maximum effect: getting senior government leaders in recipient countries to commit to a continuing and comprehensive detection effort, and helping those countries establish the legal authorities that will allow them to search traffickers and seize illicit material. The final goal is to get countries receiving detection equipment, in cooperation with international organizations such as the International Atomic Energy Agency and the governments providing the equipment, to establish effective radiation detection standards and deploy the equipment.13

Four departments—State, Defense, Homeland Security, and Energy—are responsible for implementing the plan. The Energy Department’s Second Line of Defense (SLD) program places nuclear and radiological detection equipment at international border crossings. Since 2002, the Energy Department has also been responsible for maintaining the equipment provided to twenty-one countries. The plan further notes that the SLD program “can capitalize on [the Energy Department’s] inherent technical expertise and recommend best specifications and manufacturers for radiation detection equipment.”14 Clearly, much of that technical expertise resides with NEST.

While the 2004 Strategic Plan did not explicitly refer to an overseas role for NEST, another, older document does. The October 1993 NEST Energy Senior Official’s Reference Manual notes that “NEST capabilities are also available to foreign governments as arranged by the [Department of State] in conjunction with the [Department of Energy] and [Department of Defense].” It also includes a security plan for protecting classified material “during a Nuclear Emergency Search Team (NEST) International Deployment,” which prohibits classified data from being left unattended.15

Some of NEST’s capabilities might have been provided to Greece during the 2004 Olympics, although they might not have been acknowledged as coming from NEST. The Greek government had established an Olympic Games Security Division of its Ministry of Public Order. In an effort to protect the games from terrorists, the division developed a comprehensive plan to deal with the full range of WMD threats—nuclear, radiological, biological, and chemical—called the NRBC Threat National Emergency Plan. A critical organization in carrying out the nuclear portion of the plan was the Greek Atomic Energy Commission.16

The commission’s capabilities included two 6-man teams—a Response Team and a Support Team—composed mainly of scientists available during eight-hour shifts around the clock for a three-month period. The Response Team’s duties involved on-scene monitoring, identifying and measuring radiological contamination, and recovering radioactive sources. Another NEST-type activity carried out by “mobile expert support teams” of the Greek Atomic Energy Commission were radiation surveys of Olympic venues, including the Olympic village, conducted one to two days before the games started.17

For these surveys, the Greek teams employed a variety of equipment. Among the devices they used in their patrols were sensitive neutron search detectors, a highly portable gamma spectrometer, portable plastic scintillation detectors (scintillation is a disturbance in the atmosphere), radionuclide identification devices, and a scintillation detector carried on the roof of a vehicle. Such equipment was probably very familiar to members of NEST, which might even have provided some of it or given advice on its operation, at Olympic and other sites. Certainly, one organization providing assistance to the Greek detection effort was the Department of Energy, which signed a declaration of intent with the Greek Atomic Energy Commission and the Greek customs service. A study by the Government Accountability Office reported that Department of Energy programs “provided expertise and equipment to enhance Greece’s capability to detect nuclear devices and materials at certain land borders and a major port.” It also informed its readers that a Foreign Emergency Support Team, the overall framework under which NEST provides support to foreign governments, was deployed to the Athens Olympics.18

In July 2008, the People’s Republic of China spent $2.5 million to buy portable radiation sensors—ICx Technologies’ identiFINDER radiosotope detectors—from an American firm to protect against a dirty bomb attack at the August Olympics. Help also came from the United States in the form of a contingent of NEST members, who first arrived in Beijing in June. Deployment was reportedly a response to Chinese intelligence “indicating that any attack likely would involve a radiological [dispersal] device.”19

Members might also have been involved in a cooperative effort with Russian nuclear detection and response personnel. An early November 2007 press release from the National Nuclear Security Administration trumpeted a field training exercise held in St. Petersburg from October 29 to November 2. In the exercise, according to the release, “emergency responders from the NNSA teamed up with their counterparts from the Russian Atomic Energy Agency (RORSATOM) for the first-ever joint radiological emergency response field training.” The exercise was the consequence of the 2005 Bratislava agreement on nuclear security, signed by Presidents George W. Bush and Vladimir Putin.20

The week included two small-scale exercises to test responses to the dispersal of radioactive material. It concluded with a day-long exercise that involved notification and alert procedures, mission planning, deployment of response personnel, field operations, and resolution of the crisis. The week also included discussions on the theory of radiation detection, detection equipment uses, and real-world responses to terrorism situations—topics in which NEST has a great deal of expertise.21

The nuclear security administration promised that such exercises and cooperation would continue—with regular joint training exercises to follow, including a second one in the United States to which a Russian team had already been invited.22

NEST’s major foreign operation—Morning Light—took place three decades ago. And NEST has not been called into action since then to help other countries deal with actual nuclear threats, at least as far as is known. But recently it was called into action on the high seas.

The island of Sri Lanka, officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is a bit larger than the state of West Virginia and is located southeast of India, between the Bay of Bengal and Gulf of Mannar. It has been the site of a long-running civil war between the government and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, better known as the Tamil Tigers—a group whose objectives include the creation of a separate Tamil state in the northern and eastern provinces of Sri Lanka and the elimination of moderate Tamils.

In October 2005, a radiation sensor at the Port of Colombo in Sri Lanka indicated the presence of radioactive material in an outbound shipping container. But because the port’s surveillance system, which was being funded by the NNSA, had not become operational, the container was loaded and at sea before it could be identified. As a result, American and Sri Lankan inspectors were forced to quickly examine the camera images at the port, which led them to conclude that the suspicious crate could be on any of five ships, two of which were headed toward New York.23

The container that set off the radiation sensor was, potentially, according to Vayl Oxford, director of the Department of Homeland Security’s Domestic Nuclear Detection Office, on a “pariah ship.” It was possible, even if unlikely, that the radiation came from a nuclear device loaded onto the ship by Al-Qaeda or rogue members of Pakistan’s armed forces. That mandated that the U.S. Intelligence Community make a concerted effort to find each of the five ships that could be carrying the container. Within five days, probably relying on a combination of imagery satellites and electronic intelligence satellites used to track ships, and possibly underseas sensors, the Intelligence Community settled the question of location. While the search for the ships was on, intelligence analysts examined the ships’ manifests.24

One ship, it was discovered, was bound for Canada, while another was headed for Hamburg, Germany. Following up on the intelligence provided by the spy satellites and analysts was a team at the National Security Council. The White House decided to call on NEST. One team, probably a Search Response Team, flew to Canada, while another headed to Europe. After the Hamburg-bound ship was intercepted, NEST personnel in Europe turned their radiation detection gear loose on the cargo—and found nothing.25

The two ships headed for New York were stopped by the U.S. Coast Guard in territorial waters, about ten miles off shore—far enough so that any nuclear explosion might wipe out some members of the Coast Guard and the NEST contingent but would at least leave the city of New York relatively unscathed. Members of NEST boarded the vessels, armed with their diagnostic equipment, and—no doubt to their great relief—found no indications that nuclear or radioactive cargo was on board.26

The ship that did carry the container turned out to be on an Asian route. And what it was carrying was nothing more than scrap metal mixed with radioactive materials that had been improperly dumped. The whole episode was over in two weeks, and its end result was the disposal of some radioactive waste.27

Helping a foreign government locate radioactive material, or find a nuclear device or dirty bomb in the hands of a terrorist or extortionist, and checking for radioactive material on a ship passing through a port with the government’s consent, are operations in which members of NEST would be welcomed. But there is another scenario involving NEST in which its members could be flying into extreme danger.

On one occasion, when Pakistan and India appeared to be approaching war, the United States and Pakistan discussed the possibility of U.S. forces evacuating Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal, which some analysts believe would be the only situation in which U.S. efforts to sequester or seize the arsenal would be anything “but impractical to the point of absurdity.”28 But if the country were plunged into internal chaos, the U.S. president and his senior advisors might decide to keep Pakistan’s nuclear devices out of the hands of Al-Qaeda or a radical Islamist regime.

Indeed, in the 2006 National Military Strategy to Combat Weapons of Mass Destruction, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff discusses two types of operations in which U.S. military forces would seek to keep nuclear weapons out of the hands of Osama bin Laden and his lieutenants. One is designated “elimination operations,” defined as “operations systematically to locate, characterize, secure, disable, and/or destroy a State or non-State actor’s WMD programs and related capabilities.” Finding, seizing, and disabling Pakistan’s nuclear weapons to keep them out of Al-Qaeda’s hands would seem to fit the description.29

The chairman also included “interdiction operations” as a means of keeping nuclear weapons out of Al-Qaeda’s control. Specifically, he characterized such operations as being “designed to stop the proliferation of WMD, delivery systems, associated and dual-use technologies, materials, and expertise from transiting between States of concern and between State and non-State actors, whether undertaken by the military or by other agencies of government.” In simpler terms, such operations would include finding and seizing nuclear devices or nuclear material after they have been removed from a nation’s holdings but before they can be delivered to a terrorist group.30

Such operations were also envisioned in a briefing by the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Special Operations and Low-Intensity Conflict. One briefing slide refers to “clandestine or other low visibility special operations taken to: locate, seize, destroy, capture, recover, or render safe WMD.” It suggests that such operations could take place on land or at sea. Those views were echoed by the Defense Science Board in an August 2002 briefing, which noted that a top priority for special operations forces was “Detecting, Identifying, and Localizing WMD.”31

At least one strategic analyst has argued publicly that such operations might be necessary with respect to Pakistan’s arsenal, which may consist of as many as 115 warheads: “To guard against the worst possibility—Pakistani weapons in the hands of our enemies—America should have plans ready to provide security without Pakistan’s permission, if emergency circumstances dictate, and even to take Pakistan’s weapons out of the country if the need arises. Special operations forces in the region should be kept on high alert for quick, covert incursions to disable or even relocate the weapons to prevent their capture by unauthorized people.”32

The focus on Pakistan is the result of its being both the least stable of the nine nuclear weapons states and one where there has been significant support for Osama bin Laden and Al-Qaeda, not only among the general population but also within the military and intelligence services. Pakistan has experienced four military coups. The most recent perpetrator of a coup was Pervez Musharraf, who resigned as president in August 2008. Musharraf walked a fine line since 9/11, trying to satisfy the United States that he was doing enough in the war on terror, but not doing so much that extremists found his rule intolerable. Despite those efforts, in 2003 he was the target of two assassination attempts in one week, apparently engineered by military officers with links to Al-Qaeda.33

In early November 2007, when the Pakistani Supreme Court was in the process of ruling on the constitutionality of Musharraf’s reelection while he still served as armed forces chief of staff, he declared a state of emergency, suspended the constitution, and ordered the arrest of hundreds of political opposition leaders, lawyers, and members of the media. Arrests extended across the political spectrum and included not only Aitzaz Ahsan, the president of Pakistan’s Supreme Court Bar Association, but also Hamid Gul, a former director of the Inter-Services Intelligence Directorate and architect of the Taliban.34

The turmoil surrounding Musharraf’s reelection was followed by the crisis triggered by the assassination of Benazir Bhutto on December 27, 2007, during her campaign to be elected prime minister. Just twelve days earlier Musharraf had lifted his emergency order. Ultimately, the prime minister’s job went to Syed Yousaf Raza Gillani, setting the stage for potential future clashes between the prime minister and president.35 And Musharraf’s resignation certainly does not preclude future turmoil.

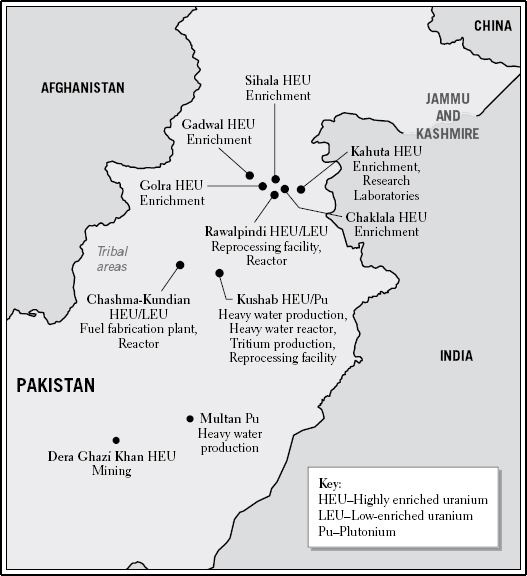

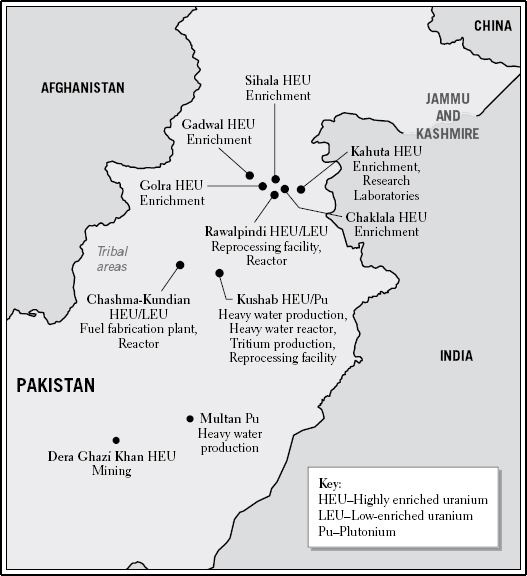

Such turmoil can be a threat to Pakistan’s political stability as well as to the security of the nation’s nuclear weapons and fissile material. Key elements of the U.S. Intelligence Community, including the CIA, the Defense Intelligence Agency, the eavesdroppers of the NSA, and the National Reconnaissance Office, which operates both imagery and communications intelligence satellites, devote significant attention to monitoring the sites known to be associated with Pakistan’s nuclear program as well as to determining where the nuclear components that make up the nation’s 80 to 115 nuclear weapons are stored. That scrutiny was stepped up after Musharraf’s declaration of emergency rule. Admiral Mike Mullen, in a mid-November 2007 Pentagon news conference, said, “I don’t see any indication right now that security of those weapons is in jeopardy, but clearly we are very watchful, as we should be.”36

But despite that effort, the U.S. government doesn’t know “with absolute certainty . . . where they all are,” according to a former U.S. official. Pakistan’s desire to keep the United States in the dark about the locations was illustrated by its refusal to allow U.S. experts direct access to the bunkers where the components were stored, even though the United States provided almost $100 million in aid since 2001 to enhance Pakistan’s nuclear security. That money purchased helicopters, night vision goggles, nuclear detection equipment, the construction of a nuclear security training center, fencing, and surveillance systems. It also included intrusion detectors and identification systems. On its own, Pakistan may have developed some form of permissive action links. But rather than permitting U.S. experts to visit Pakistani nuclear sites to install the equipment and instruct the Pakistanis on its operation, Pakistan sent its technicians to the United States for training. Nor have the Pakistanis been willing to show the equipment in action for fear of revealing too much about the locations of weapons bunkers and stored fissile material. To further complicate matters, the Pakistani military may have established phony bunkers that contain dummy warheads.37

Pakistani Nuclear Sites (Sources: David E. Sanger, “So, What About Those Nukes?,” New York Times, November 11, 2007, p. 8; Rodney W. Jones, Mark G. McDonough, with Toby F. Dalton, and Gregory D. Koblentz, Tracking Nuclear Proliferation: A Guide in Maps and Charts [Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 1998])

Of course, Pakistani officials express confidence that the arsenal is secure. In a June 2007 briefing, Naeem Salik, an officer from the Strategic Plans Division, described security measures, including perimeter security (e.g., with closed-circuit TV cameras), transportation security, materiel control, and the Personnel Reliability Program. He also addressed the “perceptions and misperceptions” concerning Pakistan’s arsenal such as worries about nuclear assets falling into the hands of “rogue generals” or “rogue scientists,” an Islamist takeover, and the assassination or elimination of key leaders.38

Musharraf himself has claimed that the nation’s arsenal is secure. In 2006, he appeared in a New York Times documentary, commenting that there was “no doubt” in his mind that Pakistan’s nuclear weapons could “ever fall into the hands of extremists.” He had previously claimed that his nation’s nuclear protections “are already the best in the world.” Those protections included restricting to a small group of senior officials—Musharraf and men he trusted—the authority toa move or employ a nuclear device. In addition, he established within the National Command Authority the Strategic Plans Division, which is responsible for nuclear weapons operations and security.39

More recently, retired Lt. Gen. Khalid Kidwai, the division chief, stated that Pakistan’s nuclear security apparatus is “second to none”—and includes a strictly controlled military chain of command, checks and balances, and the monitoring of scientists. He told foreign journalists, “There is no conceivable way Pakistan’s military weapons are going to fall into the hands of extremists.” Kidwai’s position and that of the Strategic Plans Division were confirmed by an April 2008 announcement that the command-and-control system established under Musharraf would be maintained under the parliamentary coalition led by Syed Gillani.40

The division’s senior officers are screened to eliminate candidates who are sympathetic to Islamic militants. Its Security Division is responsible for the Personnel Reliability Program, which monitors the activities of employees to uncover security risks. One employee was fired for passing out political pamphlets of an ultraconservative Islamic party and for encouraging colleagues to join him at a local mosque for party rallies. Kidwai is reported to have close ties to U.S. military officials. It was Kidwai who upgraded and expanded the Security Division. One American South Asia expert described him as “very impressive . . . Smart. Level-headed. Extremely competent in every respect” and in whom he had “a great deal of confidence in him as a wise custodian.”41

In addition, Pakistan’s practice of storing warheads, triggering devices, and delivery systems in different locales provides additional problems for those who might seek to seize them. Thieves, remarked Matthew Bunn of Harvard’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, would have to “knock over two buildings to get a complete bomb.” He also noted that “theft would be more difficult to pull off, though presumably in a crisis that might change.”42

Some U.S. officials have expressed confidence in Pakistan’s ability to maintain control of its nuclear weapons. One U.S. officer told Reuters, a week after Musharaff’s declaration that he had high confidence in the nation’s military to maintain control, that “there has been no break.” The New York Times reported that officials were relatively confident that even if Musharraf lost power or was killed, Pakistan still had reliable safeguards. Leonard Spector, a former Energy Department official and currently with the Monterey Institute of International Studies, believes that “only if there’s a complete breakdown in society, would there be an issue,” adding, “Even then, I think you’ll find a cadre who protect the assets because it’s the patrimony of the country.” And according to Neil Joeck, an expert on Pakistan with the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, around 2000 “the military realized that they didn’t have the sophisticated command and control they need.” In addition, Joeck observed, the military’s protections were strong and Pakistan’s nuclear labs “very professional.” John Brennan, a retired CIA official and former director of the National Counterterrorism Center, commented that Pakistan’s nuclear safeguards are sufficient to resist “a fair amount of political commotion.”43

Current government officials who appear to be satisfied with the state of Pakistan’s nuclear security include State Department counterterrorism chief Dell Dailey and Deputy Director of National Intelligence for Analysis Thomas Fingar. Dailey told reporters that “the security of [Pakistan’s] nuclear weapons has been first rate before, during and after the crisis the Pakistanis had.” In congressional testimony he said that while “vulnerabilities exist,” the Intelligence Community believed that “the ongoing political uncertainty in Pakistan has not seriously threatened the military’s control of the nuclear arsenal.”44

But others remain concerned, including David Albright, a physicist and former IAEA weapons inspector. “The control system is only as good as its weakest link,” he observed. He also noted that “if there is [further] instability, Musharraf is going to have less ability to exercise control. . . . With tight controls and a strong leader you are OK. But if it becomes less stable, you could have fewer constraints and someone may grab an opportunity to steal something and sell it.”45

He also commented that even if the military does not fragment and the components remain in their bunkers, there is a danger if the country is in chaos. “If stability doesn’t return, you do have to worry about the thinking of the people with access to these things,” he said. “As loyalties break down, they may look for an opportunity to make a quick buck. You may not be able to get the whole weapon, but maybe you can get the core.”46

Matthew Bunn, who noted the difficulty of outside theft, still wonders about the reliability of some of the officers guarding the weapons. Referring to the 2003 assassination attempts, and the belief that there was inside support from Pakistani military officers, he wondered, “If that’s what’s going on with the military guarding the president, you have to wonder about what’s going on with the military officers guarding the weapons.”47

And Brennan himself noted that if the country goes beyond political commotion into civil war or anarchy, it would be impossible to reliably predict what would happen. “There are some scenarios in which the country slides into a situation of anarchy in which some of the more radical elements may be ascendant,” he said. “If there is a collapse in the command-and-control structure—or if the armed forces fragment—that’s a nightmare scenario. If there are different power centers within the army, they will each see the strategic arsenal as a real prize.”48

Some analysts question whether there is anything the United States can do without Pakistani cooperation to secure those weapons. Pakistan, not surprisingly, has pledged to resist any attempt to seize its weapons. In December 2007, Gen. Tariq Majid, chairman of Pakistan’s Joint Chiefs of Staff, objected to reports by “vested and hostile elements of the international media” about the security of the nation’s nuclear weapons. “Suggestions have been made that our assets could either be neutralized or taken away towards [a] safer place to prevent them from falling into [the] wrong hands,” reads a statement attributed to Majid. It also claimed that Pakistan’s nuclear assets are very safe and secure, and the nation need not worry on that account. “There is a security system in place, which can ward off all threats, internal as well as external.”49

Daniel Markey, a former State Department official who subsequently joined the Council on Foreign Relations, believes that “there is no good military option at all” and that any U.S. military operation to forcibly extract the weapons would lead to an “incredibly ugly scenario.” A classified war game in 2006 revealed it to be an “unbelievably daunting problem,” according to one participant.50

But U.S. officials may feel that it would be an even uglier scenario if Pakistan’s nuclear weapons and fissile material fell into the hands of a government dominated by Islamic extremists sympathetic to Al-Qaeda or became vulnerable to seizure by the terrorist group. Two analysts have argued that the “United States could simply not stand by as a nuclear-armed Pakistan descended into the abyss.” Danger would come in the event of “a complete collapse of Pakistani government control,” with the vacuum being filled by Islamic extremist forces. One of those analysts also wrote that “were parts of Pakistan’s arsenal to ever fall into the wrong hands, Al Qaeda could conceivably gain access to a nuclear device with terrifying results.”51

There was, one official told NBC News, “a high degree of angst that the government would fall into the hands of bad guys and they would be in charge,” who added that there were “some in the program who are sympathetic to the radicals.” And former deputy director of central intelligence John McLaughlin noted, “I am confident of two things. That the Pakistanis are very serious about securing this material, but that someone in Pakistan is very intent on getting their hands on it.” Thus, during her January 2005 confirmation hearings, Condoleezza Rice, when questioned about the issue, responded, “We have noted this problem, and we are prepared to try to deal with it. I would prefer not in open session to talk about this particular issue.” Such contingency plans exist at the headquarters of the U.S. Central Command in Tampa, and such plans are “really, really black SAPs [Special Access Programs],” according to one expert on Pakistani terrorism—in a reference to “above top secret” programs.52

If U.S. officials do launch an operation to recover Pakistani nuclear weapons, without cooperation from that country’s military, NEST may be a key component of that effort. Strategic analyst Bruce Blair wrote that “nuclear emergency search teams, which are trained in bomb detection and dismantling, should be ready to accompany such military operations. The teams, some from Nellis Air Force Base, in Nevada, know the basic design of Pakistani weapons from defectors’ reports and could devise disabling procedures on the spot.”53

Either scenario—one in which weapons wind up in the hands of Al-Qaeda or a takeover of the Pakistani government, the locations of nuclear devices not being known with certainty in both situations—could require NEST’s search capabilities to locate them, and the capabilities of the Joint Technical Operations Team and Lincoln Gold Augmentation Team to help prepare the weapons for shipment to a safe location.

But if NEST personnel are sent into harm’s way in Pakistan or elsewhere, they will need an escort. That escort may consist of a large-scale deployment of Army forces or a much smaller deployment involving one or more special units from the Joint Special Operations Command—Delta Force, the Naval Special Warfare Development Group (formerly Seal Team 6), the Intelligence Support Activity (Gray Fox). Also along might be members of the Army’s 52nd Ordnance Group, whose insignia contains the words “Defusing Danger,” or the Defense Technical Response Group, part of the Navy EOD Technical Division.

If U.S. Special Forces were to arrive as part of a cooperative operation with the Pakistanis to relocate or protect the arsenal, NEST might not be needed. Under other circumstances, such an operation would almost certainly be NEST’s most dangerous deployment.