Bitterroot Grizzly Bear Reintroduction Management by Citizen Committee?

In their expedition across the newly acquired lands of the United States in 1803–1805, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark encountered numerous grizzly bears. Lewis described one of the first grizzlies he saw as “verry large and a turrible looking animal, which we found verry hard to kill.” Nonetheless, the party killed quite a few grizzlies during their journey, including at least 7 while camped in the Bitterroot Mountains that today form the border between Idaho and Montana. There were as many as 50,000 grizzlies living in what is now the continental United States prior to European settlement.

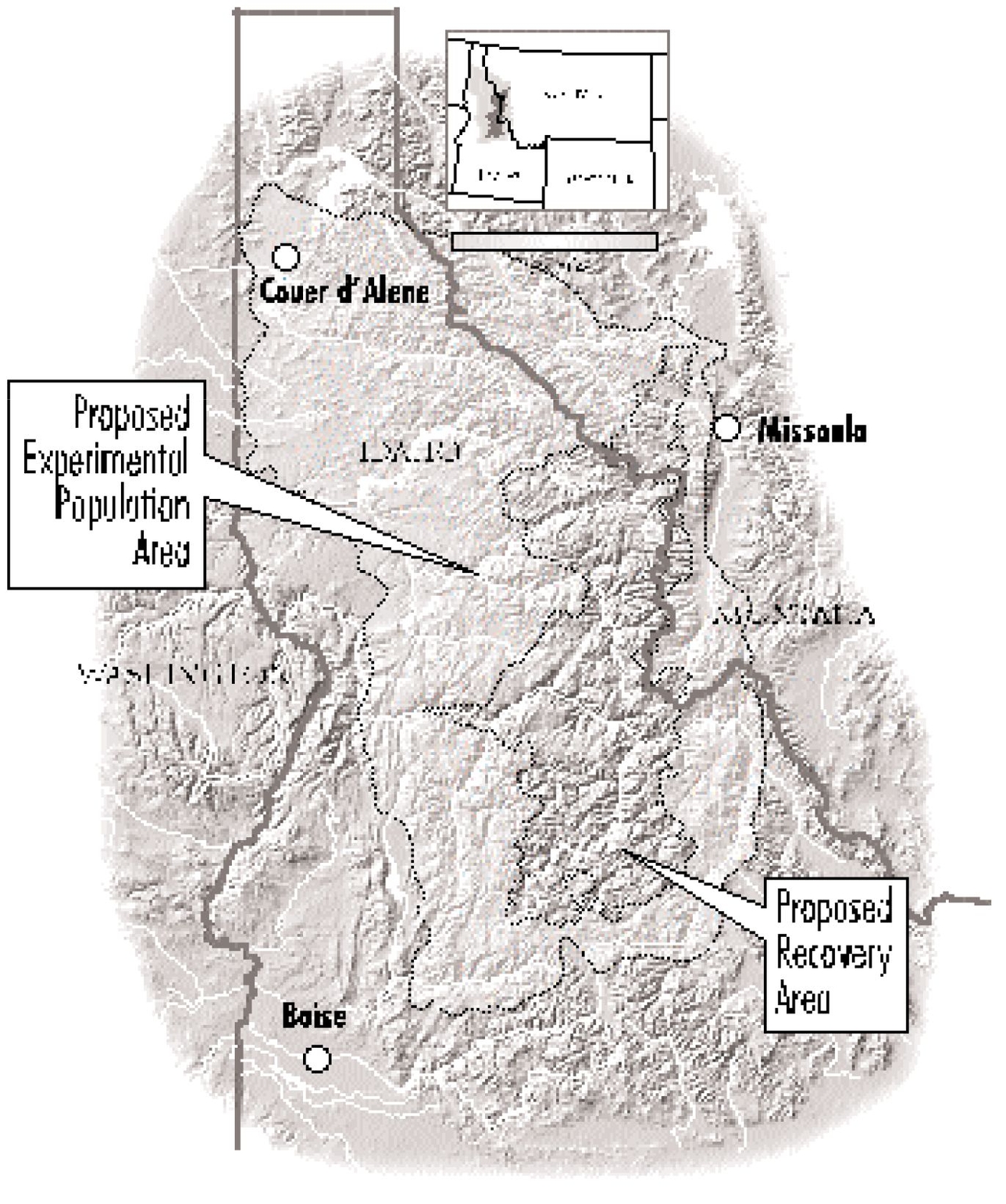

Today, there are between 800 and 1,000 grizzly bears in the lower forty-eight states, concentrated in a few isolated populations in Montana, Idaho, Washington, and Wyoming. By the end of the nineteenth century, grizzly bears in the Bitterroot Mountains had been decimated by hunting, trapping, and predator control projects. Although persistent reported sightings have led some biologists to conclude that at least a few grizzlies remain in the area, federal scientists are operating on the assumption that the grizzly is completely absent from the Bitterroot ecosystem. The nearest recognized populations are in the Cabinet-Yaak ecosystem in the northwestern corner of Montana and not far to the east of that, in the Glacier National Park–Bob Marshall Wilderness ecosystem.

Grizzly bear survival is complicated by the species’ own characteristics. Thomas McNamee, in his book The Grizzly Bear, described the bear’s survival as “a fragile thing indeed . . . the grizzly’s needs intersect (or interfere) with so many of an expanding human population’s needs or desires, and like all complex systems it is highly vulnerable to breakdown.”

Such a breakdown may occur at any of a number of vulnerable points in a bear’s lifetime. According to research summarized in the recently released Bitterroot draft environmental impact statement (EIS), female grizzlies do not mature sexually until they are four or five years old; then they take two years to raise each litter (the typical litter size is two cubs). With such a long reproductive cycle, the loss of a single female bear is a significant event in the species’ survival, and population numbers are replenished slowly.

The draft EIS also describes how adult grizzlies range over large areas and typically do not tolerate human development. Any proximity of bear habitat and human development can lead to conflicts, injury, or death—usually to the offending bear, although there is always some risk to humans. Forest roads can be a problem for bears either by discouraging their use of adjacent habitat or by leading to their death from vehicle collisions.

The largely roadless and undeveloped Bitterroot ecosystem offers the opportunity to anchor a new population of grizzlies, potentially boosting the species’ total in the lower forty-eight states by as much as a third. Many have pointed out that the Bitterroot ecosystem today lacks the abundant salmon and whitebark pine that once apparently comprised a large part of the Bitterroot grizzlies’ diet. But the bear is a notoriously adaptable omnivore, feeding on a wide variety of plants, animals, and insects, depending on seasonal abundance. The Bitterroot draft EIS concludes that, “Most authors . . . agree that successful bear recovery will be determined by the level of human-caused mortality. Grizzly bears can live within the boundaries of the [Bitterroot ecosystem], but their densities will likely be less than what could have been supported when both salmon and whitebark pine were common.”

Protection . . . Required by Law

In 1975, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) listed the grizzly bear as a “threatened” species in the lower forty-eight states after determining that although the grizzly is not yet “endangered” as defined by federal law, it is heading toward that status throughout all or most of its range. Once a species has been so listed, the Endangered Species Act requires the FWS to designate habitat critical to its survival, make sure that federal activities do not degrade the critical habitat, and write and enforce a detailed recovery plan.

The main objectives of the grizzly recovery plan, released in 1982, were (1) identify existing grizzly populations in the lower forty-eight states and establish viable population sizes for each; (2) identify the factors that could limit populations and habitats; (3) propose recovery methods; and (4) achieve recovery in at least three of the six identified populations. The ultimate goal is to reach a point at which the grizzly can be removed from the ESA list of threatened species. Of the six potential recovery areas identified in the plan, the Bitterroot is the only one not presently occupied by grizzly bears.

Biologists embarked on a number of habitat studies, taking about a decade to start getting specific about how to bring the bears back to the Bitterroot ecosystem. At that point, the FWS prepared a list of preliminary alternatives, including a proposed plan of action for the Bitterroot ecosystem. According to the plan announced in 1993, the agency expected to obtain twenty to thirty grizzly bears from British Columbia (and perhaps from established populations in Yellowstone or Glacier) and release them into the designated wilderness areas in the Bitterroot ecosystem. After the initial five-year reintroduction period, the grizzly population was projected to grow to a target of about two hundred in forty to sixty years.

Controversy began bubbling up as soon as the FWS began holding public information meetings to describe this proposal and to gather public comments. Dan Johnson, of the timber group ROOTS (Resource Organization on Timber Supply), recalls the public meetings in 1993 as “disastrous.” “People were arguing with each other, and each meeting brought new people to start the fight all over again.”

Tom France, with the National Wildlife Federation, describes widespread fears that a herd of grizzlies was figuratively poised at the U.S.-Canada border, ready to descend into Idaho and Montana and wreak havoc along the way.

It was not exactly a time of rational discourse.

Getting Beyond “No, Hell No”

After the controversy helped to force the FWS to delay publishing its Bitterroot chapter, some of the key players attended the winter meeting of the Interagency Grizzly Bear Committee at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Regional Office in Denver in December 1993. Dan Johnson was there. So were Tom France, and Defenders of Wildlife representative Hank Fischer.

Dan Johnson remembers feeling like a stranger as he walked through the halls of the FWS office. “Service employees were greeting France and Fischer by their first names. They didn’t know who I was. And France and Fischer were pursued by the press. The press showed no interest in my representation.” Both experiences reinforced Johnson’s perception that the whole recovery effort was being run in cahoots with the conservation groups.

When he had his turn to speak at the meeting, Johnson reiterated the timber industry’s position: “We don’t want any damn bears.” But, perhaps feeling the press of opinion in that room, he went on to add that if bears were going to be reintroduced, then groups like his wanted a voice in how it was going to be done.

Tom France and Hank Fischer—veterans of the acrimonious war over wolf reintroduction in the Northern Rockies—heard the “but” in Johnson’s comments. They sought him out that evening during the social hour and suggested that there might be some common ground to work from. Warily, Johnson agreed to bring some of his cohorts to meet with them. And thus a rather unlikely partnership began.

One of the early meetings took place in a small conference room at the National Wildlife Federation office in downtown Missoula. “Dan [Johnson] brought all these millworkers, who crowded around our table,” Tom France recalls. “It was big labor at its most literal.” They didn’t make any decisions except to keep meeting. And they did, driving back and forth between Idaho and Montana many times for the next year. They brought others to the table, including the late Seth Diamond (of the Intermountain Forest Industry Association) and Bill Mulligan (owner of the Three Rivers Timber mill in Idaho).

Among the most contentious issues was how to involve local interests in the grizzly management decision process. The conservationists suggested a citizen advisory committee, similar to those already used in other areas of federal land and resource management. The timber folks said no: such committees (in their experience) were often little more than window dressing and seldom influenced policy decisions. They wanted a committee that actually made decisions, which would be carried out by federal agency officials.

This had never been done, so far as anyone knew. That meant there were no models for designing the committee, although state wildlife commissions offer a rough comparison. There were questions about whether it was legal for the secretary of the interior to share management authority with a group of citizens. And the proposal raised all kinds of concerns about who would serve on the committee and under what conditions.

The group pressed on. With the help of attorney Wayne Phillips (counsel to the Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks), it drafted a detailed plan for Bitterroot grizzly reintroduction. The plan depended on the flexibility made possible by a special provision of the Endangered Species Act (ESA), commonly referred to as Section 10(j). Pursuant to 1982 amendments to the ESA, the agency is allowed (but not required) to designate reintroduced bears as nonessential (a population whose loss would not be likely to appreciably reduce the likelihood of the species survival in the wild) and experimental (a population wholly isolated from naturally occurring populations of the same species).

The “nonessential experimental” designation gives managers considerable flexibility. As explained in Appendix 12 to the Bitterroot draft EIS, Section 10(j) exempts the reintroduced population from the normal requirements of federal consultation and critical habitat designation and allows the FWS to write special rules “to tailor the reintroduction of an experimental population to specific areas and specific local conditions, including specific opposition.”

Section 10(j) does not expressly authorize the creation of a citizen management committee, but such authority reasonably may be read into the secretary’s broad regulatory authority to conserve threatened species, together with the encouragement to adapt recovery efforts of experimental populations to meet local concerns.

The coalition presented the plan to the FWS for its consideration as a new alternative. The agency ran it by attorney Margot Zallen at the Interior Solicitor’s Office in Denver. As she explained it recently, the key to keeping such a committee within the bounds of the law is to make sure the secretary of the interior retains ultimate decision-making authority. “It’s not really delegating authority,” she noted, but rather “authorizing” the committee to make certain types of decisions under the secretary’s supervision. She made a number of changes, but concluded that the basic proposal was legal.

By July 1997, when the FWS published the draft EIS, the agency’s preferred alternative included a detailed proposal for grizzly bear management by citizen management committee—in its key elements, the very plan cooked up by the conservationist-timber coalition.

Alternative One

The draft EIS for Bitterroot grizzly bear reintroduction sets out four alternative approaches. Alternative One, sometimes dubbed the “Citizen Management Alternative,” is the proposed action, the alternative currently preferred by the FWS. Its key points are the legal status of the reintroduced grizzlies (“nonessential experimental,” as described previously) and their management by local citizens.

If implemented as currently proposed, Alternative One would authorize the secretary of the interior to appoint a fifteen-member Citizen Management Committee (CMC). Committee members would include seven individuals recommended by the governor of Idaho, five recommended by the governor of Montana, one recommended by the Nez Perce Tribe, one representative of the U.S. Forest Service (appointed by the secretary of agriculture), and one representative of the Fish and Wildlife Service. Among the state-recommended members there must be a representative from each state’s fish and game agency.

The proposal requires that the CMC members “shall consist of a cross-section of interests reflecting a balance of viewpoints, be selected for their diversity of knowledge and experience in natural resource issues, and for their commitment to collaborative decision making.” Moreover, CMC members “shall be selected from communities within and adjacent to the Recovery and Experimental areas”—respectively, the 5,785 square miles of designated wilderness where the bears would be released and the 25,140 square miles of public lands in central Idaho and western Montana within which the bears might be expected to roam.

The CMC would be required to prepare two-year work plans for the secretary of the interior’s review, outlining directions for the Bitterroot reintroduction effort. The CMC’s most important responsibility is to develop plans and policies to manage the bears in the Experimental area, where grizzly occupancy is to be “accommodated” with human uses.

Above all, the committee would operate under this mandate: “All decisions . . . must lead toward recovery of the grizzly bear and minimize social and economic impacts.” If the CMC’s actions do not result in recovery, the secretary may disband the committee and resume lead management implementation for the Bitterroot grizzlies. The proposal spells out a six-month-long process by which the secretary and the CMC are to try to resolve differences.

The draft EIS was released in July 1997. The Fish and Wildlife Service hosted a series of public meetings in Idaho and Montana, which demonstrated the great divide in public opinion concerning the bear. Nearly every speaker in Salmon, Idaho, for example, expressed outright opposition to the return of the grizzly. The opposite was true in Missoula, Montana, where most speakers favored full protection for the grizzly and broader habitat designation.

Alternative One, setting forth the idea of the CMC, seemed to be left hanging in the void between these two ends of the opinion spectrum. And, while the CMC component of the proposal has attracted some support in written comments (ranging from the Missoula County Commissioners to the national AFL-CIO), coalition members have generally found their collaborative approach a hard sell.

In light of the contentious public comment period, the Forest Service decided to cast its vote in favor of a time-out. A letter from the regional foresters in the two regions affected by the decision concluded that “the success of this endeavor hinges upon broad public acceptance of a method for bear recovery. The decision-making process should allow more time for an active public outreach program that reaches down to county and local groups, elected officials, and concerned individuals.” The regional foresters suggested that the EIS be rewritten to better reflect public concerns and to “fashion a more supportable alternative.”

The Radical Center Draws Fire

“Committees are only as good as the people who create them,” says Mike Bader, executive director of the Alliance for the Wild Rockies, when asked about the Citizen Management Committee. “What do you think you’re going to get with the governors of Idaho and Montana charged with appointing committee members? Each has a track record of making timber industry appointments to sensitive positions like this.”

Most people expressing reservations about the CMC repeat this point. How can we trust the management of a sensitive species like the grizzly to a politically appointed committee, especially when its members are drawn from the communities in which opposition to the grizzly is most virulent? (Conversely, one opponent of grizzly reintroduction expressed a fear that the CMC “gives control of land management to the special interest groups supporting the proposal.”)

While efforts at sabotaging through hostile appointments are possible, CMC supporters believe that reason will prevail both in the appointments and the committee’s work. “It should be in the best interests of the governors’ offices to recommend people who can best support the goals of recovery while minimizing social and economic impacts,” points out Dan Johnson. And, adds Hank Fischer, the fact that all parties have so much at stake means that “people serving on the committee will feel that they have a lot of responsibility.”

Tom France agrees, pointing out that the timber industry has a lot riding on this proposal, and thus will pressure the governors to appoint people who will help make it succeed. As a practical matter, he does not believe that grizzly bear reintroduction is likely in the foreseeable future without the kind of local support the CMC is designed to build.

The proposed rule appears to allow the secretary of the interior to determine whether recommended committee members meet the criteria listed earlier. Thus, presumably, the secretary could nix any candidate who fails to demonstrate a “commitment to collaborative decision making” or a dedication to the committee’s goal of ensuring the grizzly’s full recovery in the area. But, other than a provision allowing the secretary to appoint committee members if a governor fails to recommend them, it’s not clear how such authority would work.

Beyond the initial question of committee membership, objections to the CMC fall into two categories, representing opposite ends of an ecopolitical spectrum. At one end are those who believe that the committee will work—too well—and will shift essential authority away from the Fish and Wildlife Service. Literature distributed by the Alliance for the Wild Rockies warns that the CMC “will run grizzly bear management, instead of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.” Alliance director Mike Bader says that the CMC is “improper because no group of local citizens can serve national interests.” People living close to natural resources, he adds, often make the worst decisions about their management.

Bader sees Alternative One as a ruse to loosen restrictions on logging and other development on federal lands throughout the 25,140-square-mile Experimental area. “It’s an end run around the courts, Congress, and public opinion,” he concludes.

Grizzly bear researcher John Craighead agrees that the CMC proposal is a dangerous precedent. In a Missoulian editorial dated August 18, 1997, he queried why the Fish & Wildlife Service “is willing to renege on its congressionally mandated responsibilities and hand them over to nonprofessionals.”

Brian Horejsi, a Canadian wildlife scientist and a board member of the Alliance for the Wild Rockies, has nothing good to say about the CMC proposal. In an editorial published in the Missoulian on October 16, 1997, he warned that devolution of land management in his country had “paralyzed democracy” by favoring special interests who benefit from resource development. “The Forest Service and FWS are by no means perfect,” he wrote, “but compared to management of local citizen committees and governor’s decree, they represent the end of the rainbow.”

Thus, in short, these objectors fear that the CMC will compromise the relatively straightforward and transparent process by which federal agency officials make decisions about grizzly management. They don’t want to lose the ability to influence these decisions at well-defined points—through comments, administrative appeals, or litigation. At the very least, the CMC represents a dilution of authority, and thus a fuzzier target for anyone seeking to challenge its decisions.

On the other hand, many voices have risen in opposition to the plan from those who fear that it represents more of the same—federal control—but in a deceptively shiny new package promising local influence. Idaho’s Governor Phil Batt, for example, told the U.S. House Subcommittee on Forests and Forest Health in June 1997 that he’s “skeptical of the Fish and Wildlife’s sincerity. . . . Make no mistake about it, this plan keeps Washington, D.C., in the driver’s seat.” Montana’s Senator Conrad Burns wrote in a July 1997 Missoulian editorial that he regards the CMC proposal as “little more than window dressing. This panel won’t have much real power.”

A representative of the wise-use group People for the West! stated in September 1997 that he liked the concept of citizen management, but that the secretary’s veto authority is “outrageous.” Instead, suggested Dave Skinner, the CMC’s decisions ought to be subject to review by the governors and secretary every fifteen or twenty years.

For his part, Montana’s Governor Racicot has conditioned his support for the plan on several additional provisions aimed at preventing the secretary from using “a pretext to reassume the authority granted to the CMC.” Among his suggestions, he recommended that the secretary and committee members submit any differences to a three-member scientific panel (essentially a nonbinding arbitration process) and that the secretary would consult with the governors of Montana and Idaho before making final decisions based on the panel’s recommendations.

The Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes, which support grizzly reintroduction, also expressed concern about the power of the CMC. Tribal Council Chairwoman Rhonda Swaney wrote in her comments that the tribes “are concerned about the potential lack of effectiveness of such a group if it does not have the ability, both real and legal, to institute its recommendations.”

These are divergent views, to be sure. They reflect a complementary pair of distrusts that pervade discussions of public resources: the distrust of rural westerners for most anything preceded by “federal,” and that of environmental activists for most anything preceded by “local.”

But these apparently divergent viewpoints are also, oddly enough, accurate reflections of the proposal’s ambiguities. It does not hand over day-today management authority to local citizens; that would continue to be the responsibility of federal and state resource managers. Conversely, it does limit the ability of the FWS to make policy decisions concerning the grizzly bears and their habitat; while retaining ultimate decision-making authority, the secretary of the interior must cooperate with local citizens.

Thus, in a sense, everyone’s fears are valid. The CMC relies on faith. Faith that the committee will be made up of competent people who sincerely want to make it work. Faith that the federal agencies will defer appropriately to the committee’s decisions but act decisively when necessary. Faith that the grizzly will benefit from all this cooperation.

And, in the end, that final article of faith may be the trickiest. As Thomas McNamee remarked in a recent telephone conversation, grizzly management is “such a piece of biopolitics.” The bears, he said, “are so extraordinarily sensitive to disturbance, and so slow to reproduce . . . their recovery is too precarious to trust to accommodating management.”

The flurry of talk has focused on how decisions will be made if and when the grizzly returns to the Bitterroot Mountains: Who will really be in charge? How will the various interested parties be able to influence decisions? And what will it mean for other reintroduced animals? The needs of the bear itself have received far less attention than the potential precedents that the plan might establish.

This is not uncommon for such high-stakes discussions. Collaborative approaches tend to be most promising when applied to solve problems among people with an incentive to develop and maintain relationships with one another. As issues become larger and involve more entrenched interests—the abortion debate and wilderness designation come to mind—the likelihood of cooperative solutions diminishes.

The citizen management proposal appears to be well crafted, solid in its legal authority, and impressive in its detail. It should and probably will serve as a model for other community-based conservation initiatives. If it is adopted, the CMC will be scrutinized at least as closely as the high-profile Quincy Library Group. And, as Quincy has demonstrated, the bright lights of public attention can be harsh indeed. The grizzly bear—that most charismatic of megafauna—may simply be too hot a subject for such innovative experimentation.

“Recovery of the grizzly bear is not a biological problem,” FWS grizzly bear coordinator Christopher Servheen remarked to Thomas McNamee, “it’s a social problem.”