ALL RIGHTS RKSHRVKI). NO PART OV THIS HOOK IN i XT I SS O I-' 1 IV V,

HUNDRED WORDS MAY Bh K I'P UODtlC. I-0 IN ANY I-OUM WITHOUT

PhRMlSSION IN" WRiriN'i; I ROM Tin. I'UIH.lSlll.tt

FIRST 1.1) IT ION

tmnttinMusly

in C f tinti(ht by hleCJefhind <//;<•/ tiffuwrt I JIM fed

K0 IN THK UNITKD STATICS Ol ; AKttJUt

This work as a whole is for

ELISABETH GIFFORD MALONE

This volume is for

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY

Home of the greatest edition of Jefferson's papers

and the Alma Mater of my son

Contents

Introduction xiii

Chronology xxv

I , (> \V V. S T <) K T 11 K DIPLOMA T I C T R I B K

I Introduction to Paris 3

II The Rebuffs of a Commissioner, 1784-1786 21

III At the Court of Versailles, 1785-1787 33

IV Confronting John Bull, I7H6 50

Til K K N O \V L K I) (; K 0 F A N <> T 11 K R W O R L I)

V Sentimental Adventure, 1786 67

VI Minister of Enlightenment 82

VII Traveling with ;i Purpose, 1787 112

VIII The Jetferson Circle, 1787-1788 131

THE RIGHTS OF M A N

IX Considering the American Constitution, 1786-1789 153

X In the Twilight of the Old Regime, 1787-1788 180

XI A Diplomat Awaits 11 is Leave, 1788-1789 203

XII Revolution Begins and a Mission Ends, 1789 214

IX T H K 11 A R N K S S 0 F S T A T E

XIII The Return of a Virginian 241

XIV New York and the Court of George Washington,

1790 * 256

XVI Working with Hamilton, 1790 286

XVII First Skirmishes over Foreign Policy 307

THE STRUGGLE WITHIN THK GOVERNMENT

XVIII Transition to Philadelphia J1 ( >

XIX Foreign Commerce Becomes an Issue, 1791 327

XX The Bank and the Constitution, 1791 337

XXI Storm over the Rights of Alan, 1791 35!

XXII Starting the Federal City 3 71

A F K U D B R E A K 8 () U T

XXIII New Actors on the Diplomatic Stage, 17 ( > 1-1792 391

XXIV An American Champion Meets Disappointments,

1792 406

XXV The Beginnings of Party Straggle, 1791-1792 420

XXVI The Causes of Discontent, 1792 443

XXVII Hamilton vs. Jefferson 457

XXVIII An Election and Its Promise, 1792 47K

Acknowledgments 4H9

List of Symbols and Short Titles Most Frequently

Used in Footnotes 492

Select Critical Bibliography 494

Long Notes so?

Index 509

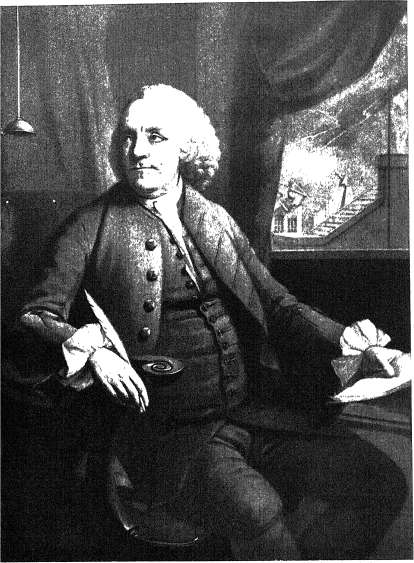

Jefferson at the Dawn of the French Revolution Frontispiece

The Grille de Chaillot 20

Benjamin Franklin 21

Maria Cosway 74

A Sample of Jefferson's Left-handed Writing 75

Jefferson as a Man of Fashion 144

The Marquis dc Lafayette 145

Angelica Church's Miniature of Jefferson 208

Jefferson in Profile 209

The Commander in Chief 262

I lamilton as a Man of Elegance 263

John Adams while Vice President 354

The Author of The Rights of Man 355

Congressman James Madison 432

Philadelphia Scene in the 1790's 433

Introduction

THIS book, which is a unit in itself, is the second volume in the scries 1 am writing under the general title, Jefferson and His Time, and a sequel to Jefferson the Virginian (1743-1784). That volume carried the story through the American Revolution, and ended with Jefferson's departure for France. The present one (1784-1792) includes his European mission, which lasted through the opening months of the French Revolution, and all but the final year of his service in his own country as the first secretary of state under the new Constitution. In the perspective of history the winning of American independence was a cosmic event, and Jefferson, during the period of his life that we have already described, proclaimed and sought to implement a philosophy which he regarded as timeless and universal, but the setting of the previous volume was chiefly local. To me the Virginia of his youth and early manhood will ever be a charming scene, but Paris and Versailles in the time of Louis XVI, London in the reign of George III, and New York and Philadelphia in the presidency of George Washington provided a far richer and more colorful background than Monticello and Williamsburg; and Jefferson participated in far more complicated movements and events in this second period of his public life than in his first. Furthermore, as the bibliography shows more specifically, the materials for these years, while sometimes disappointing, arc in general so extensive as to be positively embarrassing.

The complexity of the events and the vastness of the materials provide a sufficient explanation, I hope, for my inability to carry this volume as far in point of time as I formerly expected and indiscreetly predicted. When I wrote the introduction to the earlier book, assuming that four volumes would be all the publishers or public could be expected to stand for, I was planning to carry Jefferson to the presidency in the second. It became obvious, however, that this would be impossible if the scale of the first volume were maintained and the far more extensive materials were exploited to a comparable degree. Accordingly, with the generous concurrence of my publishers, I set out to find another logical terminal point.

Washington's unanimous re-election to the presidency at the end of

the year 1792 provides a good one. This is a convenient date in the domestic story, for a new chapter in the history of American political parties began thereafter. The period of eight and a half years that is covered in the present volume has biographical unity, since Jefferson was concerned primarily with foreign affairs throughout the whole of it. There was a marked change in the international situation early in the next year. Great Britain was then drawn into the European war and Jefferson was faced with a new set of problems as secretary of state. Some loose ends of diplomacy, left dangling in the summer of 1792, will need to be tied up in the third volume of the series, but to all practical purposes it will start with the year 1793 and extend to the beginning of Jefferson's presidency in March, 1801. That volume will trace the rise of political parties which existed in only rudimentary form in 1792, and it will be set on a background of world war and revolutionary violence, while the present one largely falls within a period of general peace and relatively philosophical revolution. It is unwise to make precise predictions in advance, but I see no reason why the presidency cannot be kept within the limits of a fourth volume, and the years of retirement covered by a fifth, if the strength of the author and the patience of the publishers and the public will hold out that long.

Throughout the months since I wrote the introduction to Jefferson the Virginian I have kept in mind the purposes that I stated there for the work as a whole, namely, that it be comprehensive and relate the man to his times and be true to his own chronology. A work of historical biography like this, predominantly narrative in form, does not lend itself to ready summary, but I will make a few observations in the light of these avowed purposes.

The goal of comprehensiveness, that is, of showing the whole man and not merely certain segments of him, is difficult of attainment at all stages of Jefferson's career and is specially so during his years in France. He was a public official, engaged in diplomatic activities which seemed relatively unrewarding at the time but are of genuine historical importance since they foreshadowed later policies and attitudes. I trust that I have treated these with sufficient fullness. His time was far less absorbed by routine tasks, however, than it was after he became secretary of state at home, and the vaunted scene of Europe offered this man of vast energy and curious mind personal opportunities such as he had never had before and was never to have again. Despite his nostalgia and his sense of the futility of Parisian life, it seems that in France

Jefferson was better able to do the sort of things he wanted to do, and to be the sort of man he wanted to be, than he ever was afterward while in public office. Never again did he live so well or indulge his tastes so freely. Never again, until his final retirement from public life, could he be to such an extent and for so long a time a detached philosopher. He may have preferred the rural atmosphere of Monti-cello, as he always said he did, but this highly cultivated man became well oriented in France, and he lived there a life of extraordinary intellectual and spiritual elevation,

He was well aware of the dangers implicit in the political and economic situation, but for him this was the hour of the full flowering of the Enlightenment, and he never gave clearer proof of his undying belief that men and society can be saved by means of knowledge. This faith, coupled with a "zeal to promote the general good of mankind by an interchange of useful things," provides the clue to his manifold activities. It was not merely that he loved music, though he said it was the favorite passion of his soul; it was not only that he gazed rapturously on beautiful buildings like the Maison Carree at Nimes; it was not merely that he found in scientific inquiry a supreme delight. He was primarily concerned with the uses of all these things. His spirit, as I understand it, is best set forth, perhaps, in the chapter entitled "Minister of Enlightenment," though there are plenty of clues and examples elsewhere in this book. He believed that men could become free and happy if they came to know more about everything, and there was a utilitarian cast to all his thinking. Thus when he spread Information in Europe about his own country, when he sent home books and architectural drawings, when he reported agricultural conditions in France and Italy and Germany, he was in the fullest sense a public servant.

At the same time, this was one of the richest periods of his life in private friendship. He had to argue with the officials of other countries in his efforts to open the channels of trade to his own country, but political controversy imposed no such barriers as it did afterwards at home and he was free to be what he liked to be - everybody's friend. He had contacts everywhere, though he set slight value on those with the world of fashion, and his most intimate associations, by and large, were with Americans. Without attempting the impossible task of describing all of his associations, I have tried to lay the emphasis where I believe he laid it: on his own domestic circle and the Americans who gathered round him as host, patron, and friend; on the little artistic group which included Maria Cosway, Angelica Church,

Xvl INTRODUCTION

and Madame de Corny; on Lafayette and liberal nobles like La Rochefoucauld and Condorcet, who were so close to him in political spirit; and on certain of the men of science and learning.

The most important single observation that should be made here about the relation of the man to his times Is that he continued to view his age as an enlightened liberal The best single clue to his political attitudes, as well as his intellectual activities, is to be found in his determination that men should be set free and kept free in order to move forward in the light of ever-expanding knowledge. Like other men of state he had secondary objectives, but he rarely if ever lost sight of his clear-purposed goal of human freedom and happiness or failed to reach his important judgments in the light of it. Among the statesmen of his time he was most notable for his high purposcfulness and it would be a grave fault in a biographer to minimize it. On the other hand, as one sees him in thoughtful action day by day, he seems to have been in the best sense an opportunist with respect to immediate ends and particular means. He was neither a doctrinaire philosopher nor a self-seeking politician, but a statesman who effected n. distinctive combination of idealism with common sense.

The two greatest events or series of events of this decade were the outbreak of the French Revolution and the establishment of a new government in the United States. One of these was a liberating movement which carried with it grave dangers of dcstructivcncss. The other was constructive, but seemed to many people to be moving toward centralized power and away from human rights. To say that Jefferson approved both developments sounds more paradoxical than it is. Actually, he approved them both 'with qualifications, and judged them both in terms of human values.

Highly exaggerated statements about his personal part in the preliminaries and first stages of the French Revolution were afterwards made by his political foes. In reality this personal part was slight, though the influence of the American example was great. As an observer he was by no means uncritical, and he reported to America with extraordinary fullness the course of events through the summer of 1789. Insofar as he exerted a direct personal influence he did so primarily on Lafayette and a few other kindred spirits. The record leaves no possible doubt that it was a moderating influence. No one was more aware than he of the imperative need for drastic reformation in France, but, despite certain stock quotations which keep reappearing in the history books, what he advocated can be much bet-

INTRODUCTION" XVli

ter described as "reformation" than as "revolution." He favored the rule of reason, not the rale of force.

He had strongly supported the successful movement for the political independence of his own country, and, in the Declaration of Independence, he had justified this revolt against what he regarded as tyranny on philosophical grounds which he deemed universal. «3kit *kis^djQ££jnotjn^ advocated the use of force to attain im-

mediate economic and social ehxis. He>^s no prophet of class warfare. He opposed all forms of political, military, and intellectual tyranny; and he championed self-government, believing that, after this had been considerably attained, economic and social ills would be progressively corrected by the orderly processes of legislation. "Rebellion to tyrants is obedience to God" — this was his motto, and he steadfastly hoped that the spirit of resistance would never die. That is the real meaning of his famous saying that is so often misapplied: -'"The tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants," In the light of previous and subsequent history, this statement may be regarded as th££ojighly realistic; but when viewed in its own setting of time and circumstance it was no invitation to bloodshed and certainly not to social revolution.! As any reader of Chapter IX in this volume caa sec, this was a private remark which was related, not to the French Revolution, but to the Shays Rebellion in the United States and to the repressive spirit which had been excited there before the constitutional convention met. Jefferson feared harsh repression at home because he had seen the results of it abroad; and he believed that traditional American freedom, even though it occasionally manifested itself in violence, was infinitely preferable to European tyranny. Many months before there were revolutionary excesses in France, he had concluded that his own free country was actually more orderly than that state was under absolutist rule.

His hope for France was not that the monarchy would be overthrown all of a sudden, but that it would assume a modified form, and head in the right direction — that is, toward individual freedom and self-government. He rejoiced when the government became committed to the fundamental and to his mind universal principles that were embodied in the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen. Beyond that point, however, he was an opportunist, and his optimistic philosophy enabled him to be patient when progress seemed slow. He was always fearful lest the impatient reformers would move too fast and create a reaction which would cause them to lose their gains. Furthermore, he saw clearly that the politically unschooled

XVlil INTRODUCTION

people of France were not ready for such a degree of self-government as Americans enjoyed. The combination in him — passionate and unyielding devotion to fundamental principles, with patience in the actual working out of reforms —was a rare one, and in it, perhaps, lies the major secret of his political success. It may be commended to our own generation as an alternative to violent revolution on the one hand and blind and stupid reaction on the other.

The Revolution developed faster than he expected or desired, but, while he was in France, the ills were less than he had feared. There were grave dangers on the horizon, a number of which he pointed out, but he viewed the situation with deep satisfaction. He approved the Revolution, on two main grounds. It marked the victory of reason over ignorance, superstition, and hereditary privilege. Furthermore, it represented the adoption by the French of principles which might be and often were called American. This was no triumph of a foreign ideology. It was a recognition of eternal truths which Americans had successfully proclaimed. The matter is summed up by a later saying of his which is so apt that I have used it more than once: "The appeal to the rights of man, which had been made in the United States, was taken up by France, first of the European nations." x He further summed up his own attitude as follows: "I considered a successful reformation of government in France, as ensuring a general reformation through Europe, and the resurrection, to a new life, of their people, now ground to dust by the abuses of the governing powers."~ His main concern, during his last months in France, was not that this "reformation" should be complete, but that it should be successfully begun.

The French Revolution did not become a major issue In American politics during the rest of the period covered by this book. It still seemed to him a "philosophical" revolution in 1791, when he was unwittingly involved in a controversy with his old friend John Adams growing out of the American publication of the first part of Painc's Rights of Man. (This is described in Chapter XXI.) He continued to support the rights of man against hereditary privilege— but so did the vast majority of the American people, and the forces of political reaction in his own country could not make much capital of the French situation as yet. They did exploit it afterwards, but most of that story belongs in another volume. The great political struggle of this period in the United States was fought on domestic lines, and the feud between Jefferson and Hamilton would have arisen if there

1 Ford, I, 147. 2 Ford, I, 129.

INTRODUCTION xlx

never had been a French Revolution. It could hardly have arisen, however, if one of the contestants had not been a champion of the rights of man, in the spirit of the Declaration of Independence. He was always that, through revolution and reaction, and more than anything else this attitude is the basis of his abiding fame.

His relation with the new American government is the major theme of the latter half of this book, and I deal in Chapter IX with his attitude toward the Constitution while he was in France. His fundamental sympathy with the constructive spirit of his friend Madison and others in their efforts to create a more effective government, and with the larger national purposes of George Washington, may be safely assumed from the fact that he himself took office as secretary of state. The best answer to the charges of disloyalty to the Constitution and Washington that were afterwards made by Hamilton and the latter's partisans is provided by Jefferson's own contemporary words and actions. Without attempting to summarize these here, I can at least say that he proved to be a devoted public servant in America, just as he had been in France, that his respect for the first President throughout this period amounted to reverence, and that he was so busy trying to make this political experiment a success that he seemed for a time almost to have forgotten the "reformation 7 ' in France. Coupled with the constructive spirit of so many of the leaders of the era, however, were certain political tendencies which he regarded as reactionary and he was deeply disturbed by these from the moment that he became fully aware of them. He summed them up in the term "monarchical," and In view of the persistence of the republican form of government in the United States this now sounds exaggerated. What he meant was that certain. American leaders, though not the people generally, wanted to turn back toward the system of hereditary privilege and oligarchic power from which the country had considerably escaped in 1776 and from which France was now struggling to emerge. He used the language of his day, not ours, opposing "monarchy" and "aristocracy," and he thought primarily in political terms, not economic.

In certain important respects the financial system which Hamilton was establishing was foreign to his thinking. Here the customary labels will not fit, for on financial questions Jefferson was characteristically conservative, while Hamilton, who was creating fluid capital by governmental act, was much more the innovator. The chapters that deal with the successive stages of Hamilton's financial policy and Jefferson's attitude toward it should leave no doubt that the sort of

property the latter understood best and valued most was real property, not securities. This lover of the land did not like the sort of financial and industrial economy that the Secretary of the Treasury was promoting, but, characteristically, he objected to his colleague's policies first and most on moral and political grounds. He deplored the mania of speculation which accompanied them and the "corruption" of the legislature by financial interest, and he deeply feared the "system" which Hamilton was building up, regarding this as potentially if not actually despotic. Yet he co-operated with his colleague cordially at first, and throughout his life he maintained a considerable degree of flexibility in economic matters. To describe him as an agrarian is to employ an Insufficient term and to rob him of part of his universality. The thread of consistency which runs through his entire career and unites him with lovers of liberty in all generations was not his attitude toward a specific economic system. It was his eternal faith in the right of men to rule themselves and his undying hostility to any sort of despotism. If we may use modern terms in this connection, he regarded the Hamiltonian system as tending toward totalitarianism.

This is the fundamental reason why he opposed it, but he first clashed with his historic rival over questions of foreign policy. The main lines of his own policy were worked out while he was in France on what he regarded as a realistic appraisal of the international situation, especially with respect to trade. Writers have often termed this policy pro-French, but it can be better described as anti-British and better still as pro-American. It antedated the French Revolution and was wholly independent of political ideology, since Jefferson distinctly preferred the British governmental system to the French at the time. Throughout his career his foreign policy was flexible — much more so than Hamilton's, I believe — and its consistency lay in his opposition, in varying degree, to those countries which, in his opinion, most threatened the security and prosperity of the United States. Throughout this period these were Great Britain and, to a lesser degree, Spain. The complications which arose from general European war belong chiefly in the next volume. The main points to be made here arc that Jefferson as secretary of state carried on the policy he had adopted while in France, and that Hamilton's interference with this, for political and economic reasons that seemed good to him, was probably the first cause of the personal feud between them.

In my opinion, Hamilton was clearly the earlier and much the greater offender against official proprieties, though he and his partisans sought to create a very different impression. The antagonism between the

two men was too deep-rooted to be explained primarily in terms of personality, but Jefferson's fears about his colleague's policies were unquestionably accentuated by his growing awareness of the powerful position which the Secretary of the Treasury had assumed in the new government and by the aggressiveness and imperiousness of the man himself.

In the effort to understand the clash within the government I have paid so much attention to the organization and operations of the executive departments that at times this work may read like the history of an administration. To me the study of the actual workings of the Washington government has been distinctly illuminating. In the footnotes and bibliography I have gratefully acknowledged some recent treatments of the subject, but scholars and writers have paid relatively little attention to it and I believe that I have corrected a number of continuing misapprehensions about the President's relations with the department heads and the actual formulation of policies. (This matter is dealt with in Chapter XV and elsewhere.) Jefferson performed services in the domestic sphere which deserve to be emphasized afresh, such as those connected with patents and the establishment of the new Federal City, and I have been impressed anew not only with the diversity of his talents but also with the closeness of his personal tie with George Washington. On the other hand, the Department of State was dwarfed by the Treasury as an administrative organization, and the procedure in these early years served to facilitate Hamilton's designs and to restrict Jefferson's influence in larger matters of policy to a degree which I did not realize before I began this book. Besides having no such access to Congress as the Secretary of the Treasury, the Secretary of State had no chance to pass on his colleague's legislative proposals before they were presented. Some of the implications of this situation, it seems to me, have been generally overlooked.

Besides seeking to understand governmental organization and procedure, I have tried to understand, not merely Jefferson, but Washington, Hamilton, and the other major actors on the scene. Others must judge whether or not there is any freshness in the interpretation of these men, but I can at least point out a few of the changes that this study has brought in my own mind. Washington, \vhom Jefferson and Madison admired so greatly and viewed so uncritically at this stage, emerges as an even more commanding and appealing figure than I had expected him to be. On the other hand, I am sorry to say, Hamilton comes out of my investigations worse than I had expected. No reader need accept any of my judgments, but they are based on the fairest reading that I could give the records of the time, including Hamilton's

Xxil INTRODUCTION

own writings. It has been said before now that he was his own worst enemy, and I believe that his own words, as cited in the last chapters of this book, clearly prove it. As I have lived through these events in spirit my wonderment has been, not that Jefferson resented the words and actions of his brilliant, egotistical, and overbearing colleague, but that he maintained so long an attitude of impersonality and was so slow to anger. I have tried to judge Hamilton's bold policies on their merits, but I cannot escape the conviction that he, more than any other major American statesman of his time, lusted for personal as well as national power. No doubt there was more personal charm in the man than appears in his writings. I may have missed something that I should have found, and it is partially for that reason that I am reproducing what I regard as the most charming of his portraits.

In this volume, as in the one that preceded it, I have tried to show the central figure as a living man and growing mind in a changing world, not as a statue in a niche or a portrait on the wall Jefferson was never static, and in this period of his life he had to adjust himself to momentous changes in external circumstances. This part of the story of his mind is essentially one of adjustment. His years in France were a time of extraordinary inquisitiveness, acquisitiveness, and intellectual stimulation, but they served to confirm him in the fundamental philosophy he had already adopted, not to give him a new one. Fie sounded more democratic in France than he ever had before, but his most striking utterances were made before the revolution and were based on the contrast between European absolutism and American freedom and self-government. The main political lesson that prc-rcvolutionary France taught him was what Americans should avoid; but, as we have already said, he recoiled against the dangers of sudden change in an old society and urged his liberal-minded friends to make haste slowly. Thus one gains an impression of unusual consistency in his basic thinking, coupled with a rare ability to adapt himself to the circumstances and conditions of the moment.

The importance of keeping the study of such a man true to his own chronology will be obvious, I believe, to any reader who has the patience to follow him step by step through this narrative. I don't try to sum him up completely anywhere and will certainly not do so here. I will say something, however, about the degree of my success or failure in determining when and how he first became a politician, in the sense that we now commonly use the term. He certainly did not become one while in France, where he was an appointed official who rejoiced that he could serve his constituency, the American people,

without being directly accountable to them or having to curry popular favor. He did not think of himself as a politician when he became secretary of state and was directly responsible to nobody but the President. Readers of this book may be surprised, as I myself was somewhat, to learn how little direct part he played in partisan politics at this stage. One reason is that the historic American parties had only begun to take form by the year 1792, when Washington was unanimously re-elected. Another is that, contrary to a very common tradition, Jefferson was extraordinarily scrupulous as an official and stuck closely to his own exacting business. By contrast, Hamilton was incessantly active in the elections of 1792, and if either of the two men should be described as a manipulator and intriguer, it was not Jefferson, but he. I am driven to the conclusion that the traditional picture of Jefferson the politician, which still lingers in the history books, is largely the creation of Hamilton and his partisans. As the latter chapters of this volume show, they also did much to establish him as a symbol of anti-Hamiltonianisni, building him up as a popular figure by the ferocity of their personal attacks. These were largely unwarranted except on the ground that the two men and their philosophies were fundamentally antagonistic. By the end of the year 1792 Jefferson was the first name in the political group which called itself republican. (I deliberately refrain from capitalizing the word as yet.) This was not because of his personal political activities, but because of what he stood for and what he was. I shall have to wait to see whether or not the statement will still seem true at the end of another volume.

To say just how Jefferson himself emerges from my investigations for the present volume would amount to retelling most of the story, but I can say that he has withstood microscopic examination even better than I expected. This is not to claim that his judgment was always right, but no one can read his voluminous state papers without gaining increased respect for his ability, and, considering the enormous body of personal papers he left, they show amazingly few spots on his character. His chief weakness, and up to this point he has not shown it often, was a defect of his politeness and amiability which caused him to seem deceptive. (See Chapter XXI and the Freneau episode.) This was also a reflection of an extreme distaste for personal controversy. With the possible exception of Washington, he was the most sensitive of the major public men of his era, and he was far more disposed to battle for principles and policies than for his own interests. Perhaps that is the real secret of his eventual political success, as it assuredly is of his enduring fame. He was a true and pure symbol

of the rights of man because, in his own mind, the cause was greater than himself.

Special acknowledgments for aid rendered me and kindnesses shown me in connection with this book are made elsewhere. At this point, therefore, I will content myself with expressing gratitude to Thomas Jefferson for the extraordinarily rich and incessantly useful life he lived and for the amazing records that he kept.

DUMAS IVI ALONE NEW YORK, June 1, 1951

Chronology

1784

July 5 TJ sails with his daughter Martha from Boston on the Ceres.

Aug. 6 TJ and his daughter arrive in Paris.

30 The commissioners (Franklin, Adams, and TJ) hold their first

meeting at Passy.

Oct. 16 TJ rents a house on the Cul-de-sac Taitbout.

Nov. 11 The commissioners make their first report to Congress.

29 William Short arrives by this date.

1785

Jan. 26 Lafayette brings TJ news of the death of his youngest daughter

in Virginia. May 2 TJ receives notification of his election by Congress to succeed

Franklin as the Minister to the French Court. 10 The first printing of the Notes on Virginia is completed. 23 The Adams family leave for London before this date. July /5 Franklin leaves Passy on his way home to America. Aug. 15 TJ proposes to Vergennes the abolition of the tobacco monopoly. Sept. 24 William Short is invited to become TJ's private secretary. Oct. 11 TJ moves to the Hotel de Langeac, where he lives during the rest of his stay in France.

1786

Jan. 7 TJ has conversed with Buifon by this time. Feb. 8 The French committee on American commerce has its first meeting. ^

Mar. 11 TJ arrives in London to join John Adams, Apr. 26 TJ sets out from London for Paris.

June 13 TJ has started the model of the Virginia Capitol on its way. Aug. 2 John Trumbull arrives in Paris and stays with TJ. Sept. 18 TJ sprains his wrist about this time.

Oct. 12 TJ writes his "My Head and My Heart" letter to Maria Cosway. 22 Calonne writes TJ about the dispositions taken to favor American commerce.

1787

January The Shays Rebellion occurs in Massachusetts. Feb. 13 Vergennes dies.

Feb 22 TJ attends the opening of the Assembly of Notables. 28 TJ sets out from Paris for the south of France.

June 10 TJ returns to Paris after his trip.

Julv 15 Polly Jefferson joins her father and sister.

August TJ writes Jay, Adams, and others about the prospects of European war. .

Sept 5 TJ takes possession of his retreat at Mont Calvairc.

Oct 12 TJ is elected as the Minister to France for three more years.

Nov. B TJ writes William S. Smith about supposed anarchy m America and the new Constitution.

Dec. 31 TJ learns that the substance of Calonne's letter of Oct. 22, 1786, has been incorporated in an arret.

1788

Mar. 4 TJ sets out from Paris to join John Adams in the Netherlands. 16 Adams and TJ complete financial negotiations in Amsterdam

about this time.

30 TJ sets out from Amsterdam for a trip up the Rhine. April 23 TJ returns to Paris and soon introduces the subject of a consular

convention to Montmorin.

June 19 TJ sends travel notes to Shippen and Rutledgc. July 30 TJ informs Montmorin of the ratification of the American Constitution.

Nov. 14 TJ and Montmorin sign the Consular Convention. 19 TJ asks a leave of absence.

1789

Feb. 23 Gouverneur Morris is in Paris by this date.

Apr. 30 George Washington is inaugurated as President in New York. May 5 TJ witnesses the opening of the Estates General. June 3 TJ sends Lafayette a proposed charter for France. July 4 TJ gives a dinner to Americans in Paris and receives a testimonial 6 TJ considers Lafayette's Declaration of Rights. 14 TJ learns of the storming of the Bastille from M. dc Corny. ,Aug. 26 The French Declaration of Rights is adopted. Leaders of the

Patriot party dine at TJ's house about this time. 27 TJ receives permission to return home on leave. Sept. 11 Alexander Hamilton is commissioned as secretary of the treasury. 26 The nomination of TJ as secretary of state is approved by the

Senate. TJ and his party leave Paris. Oct. 22 The Jeffersons embark on the Clermont. Nov. 23 The Jeffersons disembark at Norfolk. Dec. 9 TJ is welcomed by the Virginia Assembly in Richmond.

12 At Eppington, TJ receives Washington's offer of the secretaryship of state. 25 The Jeffersons arrive at Monticello,

1790

Jan. 14 Hamilton communicates to Congress his first Report on the

Public Credit. Feb. 11 Madison speaks in Congress on the funding proposals.

14 TJ accepts the appointment as secretary of state.

23 Martha Jefferson is married to Thomas Mann Randolph, Jr. Mar. 1 TJ leaves Monticello for Richmond.

21 TJ arrives in New York and reports to George Washington. Apr. 10 The first Patent Act is approved.

12 The Assumption measure is defeated in the House.

May 1 TJ begins to have a headache which largely incapacitates him for a month.

15 Washington's life is despaired of about this time. June 2 TJ removes to 57 Maiden Lane.

20 The Residence-Assumption "Bargain" is reached about this time. July 12 TJ outlines a policy in case of war between Great Britain and Spain over the Nootka Sound affair.

13 George Beckwith arrives in New York as an informal British

representative about this time.

TJ submits his Report on Coinage, Weights, and Measures. Aug. 12 Congress recesses.

15 TJ leaves for Rhode Island with the presidential party.

28 TJ replies to Washington's queries about the possible movement

of British troops through the United States. Sept. 1 TJ leaves New York for Monticello, arriving Sept. 19. Nov. 23 TJ arrives in Philadelphia to resume his duties, having left home

Nov. 8. Dec. 11 TJ begins to take possession of Thomas Leiper's house.

13 Hamilton presents his second Report on the Public Credit.

15 TJ reports to Washington on the mission of Gouverneur Morris

to Great Britain.

16 The Virginia Assembly adopts resolutions against Assumption.

1791

Jan. 19 Washington submits to the Senate TJ's Report on French protests against the Tonnage Laws.

24 TJ writes his first letters to the Commissioners of the Federal

District.

Feb. 4 TJ's Report on the cod and whale fisheries is submitted to Congress.

14 Washington reports to Congress on the Morris mission.

15 TJ gives Washington his opinion against the constitutionality of

the United States Bank.

23 Hamilton gives Washington his opinion upholding the constitutionality of the Bank.

The movement for commercial discrimination against the British is checked in Congress.

Feb. 28 TJ offers a clerkship to Freneau, who declines it.

Mar. 3 The last session of the First Congress ends.

May S TJ explains to Washington his connection with the publication of Paine's Rights of Man.

17 TJ leaves Philadelphia to join Madison on a Northern trip.

June S The first of the PUBLICOLA letters of John Quincy Adams appears.

19 TJ returns to Philadelphia after his Northern trip.

July 17 TJ writes John Adams about the episode of The Rights of Man.

19 Petit, TJ's maitre d'hotel, rejoins him.

Aug. 12 Ternant, the new French Minister, is received by the President.

16 TJ appoints Freneau as translator.

30 TJ again writes John Adams.

Sept. 8 TJ and Madison attend a meeting of the Commissioners, at which the decision is reached to give the name Washington to the Federal City and Columbia to the District. 12 TJ arrives at Monticello. Oct. 7 Hamilton has a conference with Ternant.

12 TJ leaves Monticello with his daughter Polly.

21 George Hammond, the first British Minister, arrives in Phila-

delphia.

22 TJ returns to Philadelphia.

24 The first session of the Second Congress begins.

31 The first number of Freneau's National Gazette appears. Nov. 4 St. Clair is defeated in the Northwest.

Dec. 5 Hamilton's Report on Manufactures is communicated to the

House. 15 TJ summarizes to Hammond the British actions contravening

the peace treaty. 19 Hammond reports his first "long and confidential" conversation

with Hamilton. 22 The nominations of Pinckney, Morris, and Short arc submitted

to the Senate.

1792

Jan. 11 TJ's Report on negotiations with Spain is submitted to the Senate, with the nominations of Carmichacl and Short as commissioners. IS TJ has decided to retire from office at the end of Washington's

first term. Feb. 21 TJ, acting for Washington, dismisses L'Enfant.

28 TJ and Washington talk about retirement. Mar. S Hammond presents the British case with respect to the peace

treaty. S Attack on Hamilton's special relations with Congress is narrowly

defeated. 9 William Duer suspends payment, in a time of financial panic,

and is soon arrested.

10 The House adopts resolutions regarding the new French Constitution,

Mar. 15 The National Gazette begins to attack Hamilton's policies more

vigorously. 18 TJ drafts instructions for Carmichael and Short regarding their

negotiations with Spain.

Apr. 4 TJ gives his opinion that the apportionment act is unconstitutional and Washington shortly vetoes it. May 5 Washington consults Madison about a farewell address.

23 TJ writes Washington about the causes of public discontent

and urges his continuance in office (letter received May 31).

26 Hamilton attacks TJ and Madison in a letter to Edward

Carrington.

29 TJ replies to Hammond.

July 10 TJ talks with Washington about the causes of discontent. 13 TJ leaves Philadelphia for Monticello.

25 Hamilton launches a newspaper attack on Freneau and TJ. Aug. 3 Hamilton receives Washington's letter of July 29, giving 21 objections to his "system" as reported by TJ.

18 Hamilton replies to the 21 objections.

23 y 26 Washington writes TJ and Hamilton, deploring dissensions.

Sept. 8 First ARISTIDES paper, defending TJ, appears.

9 TJ and Hamilton reply to Washington.

15 Hamilton publishes his first paper as CATULLUS.

22 First paper of TJ's "Vindication" (by Monroe and Madison) appears.

26 Madison publishes "A Candid State of Parties." Oct. 5 TJ returns to Philadelphia.

31 Pamphlet against TJ, Politicks and Views of a Certain Party, is

published by this time. It is generally assumed by the leaders that Washington will

accept re-election.

Nov. 16 By this date TJ is informed of republican gains in the congressional elections. Dec. 9 TJ informs Leiper that he will give up his house after three

months.

11 TJ makes a private note on the Reynolds affair. 19 TJ is sure of the re-election of Adams as vice president by now. 22 Hamilton's last paper as CATULLUS appears. 31 The last paper in TJ's "Vindication" appears.

s s

s s

s s

^ Lowest of the Diplomatic Tribe J

s s

s s

} j*».jT'f.^'*-jr*.jr f . J j'"t_ J s**^-f_^'m_jrt .ji»mJrt.j*m.*~t jf, JT-» ^»« s*».jr»^r*-jr-*^f*^-*J jr-*J jr»^f*

Introduction to Paris

EARLY in August, 1784, Thomas Jefferson and his daughter Martha — familiarly known as Patsy — arrived in Paris. It took them a month to get there from Boston, whence they had sailed somewhat by accident, and five and a half years to get back to their home in Virginia, where his dearest memories lay buried with his wife. He did not anticipate that long a stay in France, for he w r ent there on a special mission limited to two years, even though its objectives were as broad as the face of Europe. At this place, or any other that might seem appropriate, he and John Adams and Benjamin Franklin were to negotiate for the young American Republic as many treaties of amity and commerce as they could. The famous trio of the Declaration of Independence was reassembling in a far larger and more renowned city than Philadelphia.

The eldest commissioner, then much the most eminent of the three, had been serenely awaiting the coming of the others. The venerable Dr. Franklin was living in the village of Passy, west of the city and adjoining the Bois de Boulogne, and was fully entitled to rest on his bright laurels. Since he was seventy-eight years old, had "the stone" (in his bladder), and was pained by the jolting of a carriage, he remained as much as he could at Passy and let the world come to him. Jefferson promptly paid his respects to him after his own arrival, and when the commissioners began to hold formal sessions they did so at the old man's house. Franklin always liked his agreeable colleague from Virginia, and had wanted him to come to France with him eight years earlier; he was not at all displeased at the report already going the rounds that Jefferson would succeed him as minister to the Court of Versailles some day. 1

1 TJ's Account Book, Aug. 6, 10, 1784; Franklin to John Adams, July 4, 1784, in the latter's Works, VIII, 207.

NOTE. Explanation of the abbreviations used In the footnotes and further details concerning the works referred to may be found in "Symbols and Short Titles" and "Select Critical Biography" at the end of this book.

John Adams, who was also familiar with the French scene, was a week behind Jefferson in reaching the city. He had recently been in the United Netherlands with his son John Quincy, and had gone from there to London to meet his wife and daughter, whom he was hungry to see after more than four years' separation. Bringing his family with him to France, he took them to the village of Autcuil, beyond Passy and adjoining the Bois de Boulogne, where he loved to walk. It was here at Auteuil that he had recently recuperated after the peace negotiations which ended the American Revolution, and he regarded his house and garden, and his situation away from the "putrid streets" of Paris, as all that heart could wish. Jefferson liked both the place and the family and went there very often. 2

The secretary of the commission, Colonel David Humphreys of Connecticut, completed the little official circle. Jefferson had hoped that he and this recent aide of Washington could sail together, but Humphreys left New York on the Courier dc FEuropc ten clays after the Ceres lifted anchor in Boston Harbor, and arrived in Paris just about that long after Jefferson. A rather pretentious young man and a budding poet, he described, his voyage to the Old World and his own emotions in an epistle in verse addressed to his friend Timothy Dwight. 3

Jefferson, who sailed on the Ceres, left a prosaic and more precise record of his first crossing. Every day at noon he recorded in his account book the latitude and longitude, the distance covered, the winds, the reading of the thermometer; and he made observations about whales, sharks, and other strange creatures as he saw them, 4 Also, with the help of a grammar and a copy of Don Quixote,, he studied Spanish. Years later he remarked to John Quincy Adams that it was a very easy language since he had learned'it in a voyage of nineteen days. "But," said the serious son of his old friend, "Mr. Jefferson tells large stories." 5 Both of the Jeffersons enjoyed the voyage. Having favorable winds, they made an unusually quick passage and they were blessed with sunshine and smooth seas nearly all the way. Though an indifferent sailor, the father was hardly sick at all The passengers were few — six, Patsy said — but they were congenial The owner of the practically new ship, Nathaniel Tracy of Newburyport, was on board, ready to talk with the Virginian about the state of commerce,

2 John Adams, "Diary," Aug. 13, 17, 1784 (Workf, III, 389).

3 F. L. Humphreys, Life and Times of David Humphreys (1917), I, 307-309.

4 Account Book, July 5-25, 1784.

* Memoirs of J. Q. Adams, I (1874), 317; Nov. 23, 1804.

At the time this was a discouraging subject, and they may have regarded it as a portent that they ran into thick weather as they neared the European coast. 6

Jefferson had intended to transfer immediately to a vessel bound for France, without setting foot on England, but they fell in with none and at the end of the voyage Patsy was ill. They landed at West Cowes, and on her account they remained several days at Portsmouth, though her condition was not too serious to prevent her father from making a little trip inland and doing a bit of shopping. By the last day in July they were at Havre, after a brief but stormy passage of the Channel. The rain was violent and the cabin so small that they had to crawl into k. Patsy slept in her clothes on what she called a box, and in these cramped quarters her distinguished father must have regretted his long legs. They ran into further difficulties on landing at Havre, owing to their unfamiliarity with French as a spoken language and Jefferson's ignorance of the wiles of porters. One of the latter roundly cheated the gullible American, who kept his accounts carefully but never had any taste for haggling. As they followed the Seine to Paris during the first days of August, beggars surrounded their carriage wherever it stopped. They found this shocking, but both of them greatly admired the countryside. Patsy had never seen anything so beautiful; after the forests of Virginia it seemed a perfect garden. Jefferson himself reflected that no soil could be more fertile, better cultivated or more "elegantly" improved. It was not he but his daughter who wrote back to America about the fine churches and stained glass they saw on the way; he looked first at the land and pronounced it good. But he kept on regretting that they had not brought the bright skies of Virginia with them to France; it was more than a year before he could report a wholly cloudless day. 7 He liked neither Gothic arches nor shadows; he admired classic columns and loved the sun.

They lodged first at the Hotel d'Orleans in the Rue de Richelieu, near the Palais-Royal, moving four days later to a hostelry of the same name on the Left Bank in the Rue des Petits Augustins. Desiring to fit Patsy out in the Parisian manner, the widower — before proceeding upon official business — summoned staymaker, milliner, and shoemaker, meanwhile buying a sword and belt, buckles, and lace ruffles

6 The best accounts of the trip are in Jefferson's letter to Monroe, Nov. 11, 1784 (Ford, IV, 5), and in Martha's to Mrs. Elizabeth Trist, August, 1786 (Edgehill Randolph Papers, UVA). For all his travels, Edward Durnbauld, Thomas Jefferson, American Tourist (1946), referred to hereafter as Dumbauld, is invaluable.

7 Oct. 16, 1785; daily chart of temperatures in Account Book.

for himself; and, before the first formal meeting of the commissioners, he got his young daughter placed in school. This was at the Abbayc Royale de Panthemont, a convent much patronized by English people and considered the most genteel in Paris. It is said that no pupil was admitted except on the recommendation of a lady of rank, and that a friend of the Marquis de Lafayette sponsored Martha. 8 After three years' observation of the convent Jefferson termed it the best house of education in France, and he assured his sister in Virginia that no word was ever spoken to the Protestants on the subject of religion. 0 There were fifty or sixty pensioners when Patsy arrived, Including three princesses each of whom wore a blue ribbon over the shoulder, Her father visited her very frequently until she got oriented, and site fell into the life quickly and happily. She wore a crimson uniform, laced behind; she came to be known as "Jcfly" and soon could chatter like everybody else in French.

Her father said that he never became fluent in the language, though eventually he made himself understood; he even claimed that he could not write it, though there is plenty of record that he did. 10 His progress was naturally slow, since he was past forty and, his first associations being predominantly American, he rarely got beyond the sound of his native tongue. The Americans who happened to be this far from home sought each other out and constantly exchanged hospitalities; they comprised a close-knit group. Jefferson was one of the most honored members of this little band from the first, and after the departure of Adams and Franklin he became its acknowledged chief.

His closest personal relations during his early months in France were not with Franklin, who was nursing his gout and stone and already had as much social life as he could manage. The younger man heard a good many of the elder's bons mots and had the palate to relish them, and he picked up a number of stories about Franklin which have got into the biographies, but their meetings were chiefly official. Mutual cordiality marked their intercourse throughout life, but Jefferson was more intimate with John and Abigail Adams. They were much closer to him in age and less sought after by others, while their do-

8 Account Book, Aug. 26, 1784; later story by Virginia Trist (Eclgchill Randolph Papers, UVA). Lafayette was still in America at this time, but the tradition may be correct.

*To Mrs. Boiling, July 23, 1787 (Domestic life, p. 130). Other comments chiefly from Journal and Correspondence of Miss- Adorns (1841), p. 27 (hereafter referred to as Miss Adams}. See also Helen D. Bullock, My Head and My Mean (1945), pp. 5-6; and, for an account of the place, Thiery, Guide dcs Amatmrs ct des Strangers (Paris, 1787), II, 568-569.

10 The best discussion of his use of French that I have seen is by J, M. Carricrc, in French Review, XIX (May, 1946), 398-399.

mestic life was more to his taste than Franklin's less conventional menage.

Jefferson's appointment had given John great pleasure. "He is an old friend, with whom I have often had occasion to labor at many a knotty problem, and in whose abilities and steadiness I always found great cause to confide," he said. 11 His associate, younger by seven and a half years and taller by six inches or more, had not wounded his vanity as yet. Adams, also a very domestic being, was more fortunate in that his wife and two of his children were with him. John Quincy was already impressively learned at seventeen. Abigail, wife of John, was more than a year younger than Jefferson, and the daughter of the same name was nineteen. The girl was known as "Abby" in the family, but everybody else called her "Miss Adams." In that formal age Patsy was referred to by her elders as "Miss Jefferson," though she was only twelve.

The two families met almost immediately as the dinner guests of Thomas Barclay, the American consul general, and were on the friendliest terms thereafter. At first Jefferson dined more often at Auteuil than the Adamses did with him in Paris, for he was at a disadvantage as a host until he got a house. 12 But he maintained the balance in other ways and was specially agreeable to the children. Thus, after a dinner at Dr. Franklin's, he took Abby and young John to a concert at the Chateau of the Tuileries, where they saw the brother of the King of Prussia; and at his invitation the family went a few days later to Patsy's convent to see two nuns take the veil Miss Adams cried, like many others, but she was glad to learn from Miss Jefferson that ordinarily the place was not so sad. Most of these family memories were sweet and they survived the storms of controversy and ravages of time. Shortly before his son became the sixth President of the United States, aged John Adams wrote from Quincy to his somewhat less aged friend at Monticello: "I call him our John, because, when you were at the Cul de sac at Paris, he appeared to me to be almost as much your boy as mine." 13

Colonel Humphreys, whose stiff manner greatly puzzled young Abigail at first, generally accompanied the more agreeable Jefferson to dinners. Then thirty-two, he was a dark man of military bearing who did not look the part of a poet. Like his friend John Trumbull of Connecticut, he recognized Jefferson as a man who combined literary

11 Adams to James Warren, Aug. 27, 1784 (Works, IX, 524).

12 Early dinners are described in Miss Adams, pp. 14, 16, and Letters of Mrs. Adcmis (1848 edn.), p. 194 (hereafter referred to as Mrs. Adams).

ls Oct. 4, 14, 1784 (Miss Adams, pp. 20, 23-27); J. Adams to TJ, Jan. 22, 1825 (Works, X, 414).

merit with public virtues; he brought and presented to him with the author's compliments a copy of Trumbull's epic work, McFingaL" But the historic stature of the Secretary of the Commission is better reflected in his epitaph than in his own poetry:

To sum all titles to respect, in one —

There Humphreys rests — belov'd of Washington. 15

He stood next to Washington when the General resigned his commission at Annapolis, but he was a sort of protege of Jefferson in these Paris days, the first though not the most cherished of the young men who gathered about the generous Virginian and basked in the sunshine of his good will. Jefferson was only a little taller than this recent soldier, but he took him under his wing at once. I Ic engaged lodgings for him in advance, immediately invited him to live with him, and made him a member of the family from the time that he himself acquired a house. About the middle of October Jefferson rented one on the Cul-de-sac Taitbout (now the Rue du Ilcldcr) near the Opera. He kept it only a year, but this inveterate builder had two rooms remodeled while he was there. He assured Humphreys that he would really add nothing to the expense by moving in, and when William Short arrived late in the autumn said the same tiling to him."

Short was more than a protege; to all practical purposes he was a son. A Virginian and twenty-five years old, he had attended William and Mary, where he was one of the earliest members of Phi Beta Kappa. His acquaintance with Jefferson probably arose from his relationship with the Sldpwiths, with whom Jefferson was connected by marriage. The former Governor was one of Short's examiners when he was admitted to the bar — George Wythc being the other — and had guided him in his studies before that. But the young lawyer developed an insuperable aversion to practice, and was dissatisfied with the honorable position on the Virginia Council to which lie was elected at an unusually early age. Fie wanted to go abroad with Jefferson — as his private secretary if he should have one, but to go with him in any case. For various reasons they were unable to go at the same time, but Short followed his patron after a few weeks and made headquarters with him from the first. For a time he went into a French household at Saint-Germain to improve himself in the lan-

"Trumbull to Jefferson, June 21, 1784 (MHS). Truinbull, the poet and jurist, is not to be confused with the painter of the same name who became an intimate friend of Jefferson's a little later.

15 Humphreys, Humphreys, I, i,

16 Humphreys to Washington, Nov. 6, 1784 (ibid., I, 317).

guage, and not until summer could anything official be found for Mm to do. Soon after that, Jefferson made him his secretary; and if he did not already regard him as the greatest young man he knew, he soon came to. This slim Virginian had none of the stiffness or pomposity of the poetic Colonel; he had social grace and fell into the little American circle with ease. Miss Adams and her mother, who described him as modest and soft in manners, liked him from the start. Also, he formed intimate French connections — rather more intimate than his adopted father liked. 17

Jefferson was a generous host from the beginning, as his nature and tradition required, but he was junior to both Franklin and Adams and regarded his official position as obscure. The specific task he had assumed was formidable enough. As Franklin said, if they were to make twenty treaties they were not likely to eat the bread of idleness. 18 Idleness was the last thing on earth the youngest of the commissioners wanted, but these representatives of a feeble Republic had to play a waiting game. They met at Passy every day at first, and they dispatched many letters, but during the autumn and winter they saw no concrete results. Jefferson's reception by Vergennes and other officials was as polite as he could wish, but the fact was that he found himself to be a person of no particular importance, on the outskirts of a formal Court deeply engrossed in its own affairs. The political scene in the Monarchy was somnolent; and in a few months he described himself and his fellow commissioners as "the lowest and most obscure of the whole diplomatic tribe." Except in physical stature he was the lowest of the three.

Fie soon realized that he was going to run into financial difficulties. 19 When Franklin and Adams came over, actual expenses were paid

17 Short arrived by Nov. 29, 1784; Jefferson to Gov. Va., Jan. 12, 1785 (Ford, IV, 26). See also Miss Adams, Dec. 1, 1784, Jan. 27, 1785 (pp. 35, 45); Mrs. Adams, Dec. 3, 1784 (p. 207). He was born Sept. 30, 1759, the son of William Short and Elizabeth Skipwith (Family Chart in Short Papers, LC). The recommendation of Jefferson that he be admitted to the bar was on Sept. 30, 1781 (VSL, courtesy JP). Of several early letters from Short to Jefferson, those of May 8, 14, 1784, are most interesting (LC, 1689-1690, 1697-1699). See also O. M. Voorhees, History of Phi Beta Kappa (1945), ch. I; and A. B. Shepperson, John Paradise and Lucy Lftdwell (1942), pp. 308-309. There is further information in the useful master's essay of G. G. Shackelford, "The Youth and Early Career of William Short" (UVA, 1948).

18 Franklin to John Adams, Aug. 6, 1784; (Adams, Works, VIII, 208-209). Their official activities are described in the following chapter.

19 To Monroe, Nov. 11, 1784 (Ford, IV, 11-13). Good later summary in letter to Madison, May 25, 1788 (ibid., V, 12-16). See also TJ to Samuel Osgood, Oct. 5, 1785 (L.&B., V, 163-164).

by Congress, but the salary of a minister was afterwards fixed at 2500 guineas a year, and with Jefferson's appointment it was reduced to 2000. Franklin said that his American visitors would have to content themselves henceforth with plain beef and pudding; and in Jefferson's opinion, the reduction in the allowance was an important reason for the Doctor's insistence on a recall. 20 Franklin was less frugal in practice than in theory but he lived plainly, Jefferson said, increased debt was inevitable on a reduced stipend and Poor Richard was averse to that. Adams was no little mortified that a fifth of his salary had been cut off at the very time when the arrival of his family had added to his expenses. He realized that he must be less hospitable, though the interest of the United States would be better served by his entertaining more. 21 Jefferson regarded his friend Abigail as a most excellent "economist," but in spite of her care and their modest life, he doubted if the Adamses could make both ends meet. The financial problems of American diplomats were distinctly embarrassing at the beginning of the Republic — as they continued to he for generations.

Jefferson was granted an advance of two quarters' salary, but no provision whatever was made for his outfit. Soon after he moved into his first Paris house he wrote James Monroe, as a friend and a member of Congress, that his furnishings and equipment cost him nearly 1000 guineas and he would have to stay in debt to Congress for them. He afterwards revised his figures upward until they exceeded a year's salary; and, besides being unable to refund the advance, he went deeply into debt to private creditors. He continued to insist that an allowance of one year's salary for furnishings and equipment was necessary and proper, but not until after he had returned to America and been for some time secretary of state did he make his point. Throughout his entire stay in France he was in the dark about the intentions of an indifferent and impecunious Congress in this crucial personal matter. 22

The fundamental difficulty arose from no extravagance on his part; it grew out of the confusion of American finances and political affairs. He cannot be blamed for buying furniture rather than renting it at the exorbitant annual charge of 40 per cent. On the other hand, he was personally fastidious, adding to his financial difficulties by remodeling and redecorating houses in which he did not stay long,

20 Franklin to Adams, Aug. 6, 1784 (Adams, Works, VIII, 208-209); TJ to Madison, May 25, 1788 (Ford, V, 14-15); Carl Van Dorcn, Benjwmn Franklin (1945 edn.),pp. 636-637.

^ Adams to James Warren, Aug. 27, 1784 (Works, IX, 525-526).

23 For the final outcome, see pp. 204-205, this volume, csp. note 6.

and getting more and better furnishings than he needed. 25 During his first winter at Paris he told Monroe that he was living about as well as they did when they kept house together in Annapolis as members of Congress. He kept a hired carriage (buying one in the spring) and two horses, but at first he could not afford a riding horse. After he succeeded Franklin (in May, 1785) a better style of living was expected of him, he thought. "This rendered it constantly necessary to step neither to the right nor the left," he reported, and "called for an almost womanly attention to the details of the household." 24 From the beginning he had a full staff of servants, including a valet de chambre. 25 The well-known Petit came into his service in May, 1785, but left him after a time and did not become his maitre d'hotel until later. Humphreys and Short had servants of their own and paid them, but there were that many more mouths for Jefferson to feed. He could hardly have been happy in a small establishment; and his nature and habits demanded comfortable, agreeable, and hospitable living. He was probably the least thrifty of the three American ministers, and had the most expensive tastes; but by the standards of Versailles he was economy itself. In his first summer he wrote John Adams, then in London, that he could not follow the Court to Fontainebleau, though the season was a particularly good one for doing business with Vergennes. The rent of a house there for a month would have taken almost his entire salary, leaving him nothing to eat. Fie viewed without regret the departure of the beau monde from the city in summer. "We give and receive them you know in exchange for the swallows," he afterwards said. 20 Of his own longing for the country, however, there can be no doubt.

The first months of this transplanted Virginian in the French metropolis were relatively gloomy, partly because he was not well. Abigail Adams reported sympathetically in December that he had been confined to his house for six weeks and, though recovering, was still feeble. 27 Flis confinement actually extended through most of the winter. Such a "seasoning" was the common lot of strangers, he reflected, but

23 Items for wallpaper, carpentering, plastering, etc., in Account Book, Dec. 20, 30, 1784 and Jan. 15, 1785. The rent itself was supposed to be paid by Congress. For his purchases, see Marie Kimball, The Furnishings of Monticello (1940), pp, 5-6.

2 *To Madison, May 25, 1788 (Ford, V, 15-16).

25 The scale of his establishment from the beginning is suggested by the purchase on Oct. 22, 1784, of 6Yz doz. plates and 3 doz. carafes (Account Book).

26 TJ to John Adams, Aug. 10, 1785 (L. & B., V, 59); to Humphreys, Aug. 14, 1786 (zm, V, 401).

27 Dec. 9, 1784 (Mrs. Adams, p. 216).

he believed that his experience was more severe than the average. He particularly regretted the unwholesomeness of the water and the dampness of the air. Others condemned the climate even more roundly than he. Baron de Grimm reports a poem in a single verse written in dispraise of the four seasons by a gentleman of the Court;

Rain and wind, and wind and rain.

"At least you will not find it too long," the gallant author said to a friend. The friend replied, "Pardon me it is too long by half. Wind and rain would have said all" 2S The sun was Jefferson's great physician and by spring he regarded himself as almost re-established by it; in the middle of March he was walking four or five miles a day.

His moods always varied with the seasons, but he was never again so gloomy as in that first grim winter, when, besides being ill, he had devastating news from home. Patsy was in Paris enjoying perfect health, but he had left two daughters with Francis and Elizabeth Eppes in Southside Virginia, knowing that the little girls were much too young to travel and could not be in better hands. But in January, through letters brought from America by Lafayette, he learned that whooping cough, "most horrible of all disorders," had attacked the children at Eppington and carried off his youngest daughter, Lucy Elizabeth, then two and a half years old, and one of 'her little cousins. Polly Jefferson, now six, had coughed violently with the others but was quite recovered. Under the burden of double tragedy Elizabeth Kppcs regarded life as scarcely supportable. Jefferson wrote his brother-in-law, Francis Eppes, that since nothing could possibly describe his state of mind or bring any comfort, he would simply dismiss the deeply painful subject. To Dr. James Currie he wrote more freely, speaking morbidly of the "sun of happiness, clouded over, never again to brighten," and of "schemes of life shifted in one fatal moment." He was back in the mood of melancholy that had followed his wife's death, but his mind soon shifted to the future. Now having only two daughters, he was quite sure that he wanted both of them with him, and the effort to get Polly from Eppington to Paris became one of his major tasks from the time he knew that his own stay would be extended. The task required complicated planning, much persuasion, and some guile, and it consumed two more years. Not until the summer of 1787 was the circle of his little family completed, and not until then did the American Minister become fully reconciled to life in France. 29

28 Historical and Literary Memoirs . . . -from the Correspondence of Baron dc Grimrn> II (London, 1814), 123-124.

^Francis Eppes to TJ, fall of 1784, and Elizabeth Eppes to TJ, Oct. 13, 1784

By the spring of his first year, however, life was quickened by both the season and the march of events. The state of his health, combined with his grief, had caused him to forswear dining out for four or five months, and he did not think proper to make an exception even of the Adamses, though they occasionally dined with him. Late in March, John spent the evening with him, and on that very evening the Queen was delivered of a son. Lafayette told John Quincy the next day she was so large that they really expected twins; Calonne, the Comptroller General, had prepared two blue ribbons in case two princes should be born. A few days later Jefferson and the Adamses, on invitation of Madame de Lafayette, went to Notre Dame to hear the Te Dernn sung in thanks for the birth of a prince, the King himself assisting. All the polite world was there and Jefferson must have enjoyed the fine music. On the way he remarked to young Abigail — with a degree of exaggeration — that there were as many people on the streets as in the whole state of Massachusetts. 30

Within another month Jefferson was officially informed that he was to succeed Franklin, while John Adams learned with great satisfaction that he was going to England, where he was sure that he could accomplish much. A round of hospitalities was in order, and Jefferson gave a dinner. 31 The Marquis de Lafayette and his lady were guests, along with a few other nobles. The Adamses headed the American delegation and John Paul Jones was there, being addressed as Commodore. Abigail had previously noted that the famous sailor was not stout and warlike but small and soft-spoken, and that he understood the etiquette of a lady's toilet as perfectly as he did the rigging of his ship, Jefferson followed foreign dinner customs which seemed strange to the American matron. Before dinner the men stood or walked about, shutting off the fire from the seated ladies, and there was no general conversation at the table or afterwards but only tete-a-tete. A stranger would think everybody was transacting private business. Abigail was distinctly impressed by French politeness, nevertheless, and greatly liked this host, especially when he visited them in a friendly, informal way. "One of the choice ones of the earth," she

(Domestic Life, pp. 101-102); Dr. James Currie to TJ, Nov. 20, 1784 (LC, 1864); TJ to Francis Eppes, Feb. 5, 1785 (Randall, III, 588); Currie to TJ, Aug. 5, 1785 (LC, 12331). Jefferson got the news on Jan. 26. The next day young Abigail Adams noted in her diary that he was "a man of great sensibility and parental affection," and that he and Martha were greatly affected by the tragedy (Miss Adams, p. 45). The story of Polly's arrival is told in this volume, ch. VIII.

30 Memoirs of /. Q. Adams, Mar. 27, April 1, 1785 (I, 15-19); Miss Adams, April 1, 1785 (pp. 65-H58).

. Adams, May 7, 1785 (pp. 240-241; see also p. 208). '

called him, and when she went to England, after a succession of dinners, she was even more loath to leave him than she was her garden. She thought of him particularly when she heard the "Messiah" at Westminster Abbey. It was sublime beyond description, she said, and would have gratified his "favorite passion" to the highest degree. She started a correspondence with him which he was delighted to continue, and in their hands even purchasing commissions assumed charm and grace. 32

Shortly before the departure of the Adams family Jefferson went through certain ceremonies at Versailles. After communicating his appointment to Vergennes he delivered his letter of credence to the King in a private audience; then he had his first audience with Louis XVI, Marie Antoinette, and the Royal Family in his quality as minister plenipotentiary of the United States to the Court of Ills Most Christian Majesty. 33 He was not much impressed by these or any other ceremonies and he never admired this queen, but the numerous notes of congratulation he received — all phrased in formal but delightful terms of politeness — showed that he was now an official of established standing. Fie was entitled to attend the King's levee every Tuesday and dine with the whole diplomatic corps afterwards, but he was never so thrilled by this experience as was young David I him-phreys, and he had no high opinion of the diplomats generally. Toward the end of his ministry he told Gouvcrncur Morris that they were really not worth knowing. He made a slight exception of the Baron de Grimm, the minister of Saxe Gotha, whom he found the most pleasant and communicative member of the entire corps. Rousseau's biting anecdotes about him (in the latter part of the Confessions) appeared in print after Jefferson left Paris, and Grimm's famous Correspondmce was published after he had grown old. The American saw him as "a man of good fancy, acutcncss, irony, cunning and egoism," with no heart and not much science, but with enough of everything to speak its language. This oracle of society in letters and the arts might easily have introduced Jefferson to Diderot had the Encyclopedist lived a few months longer. Diderot died the week before the Virginian reached Paris. Rousseau, with whom he would have had much less in common, had been dead some six years by then; 54

a2 Mrs. Adams to TJ, June 6, 1785 (LC, 2136-2137); TJ to A/Irs. Adams, June 21, 1785 (Ford, IV, 60-64). See also Mrs. Adams, p. 248.

33 Account Book, May 17, 1785; documents, LC, 2082-2083.

34 Humphreys to Washington, July 17, 1785 (Humphreys, I, 32H); G. Morris, Diary of the French Revolution (1939), I, 135; comments on Grimm and the philosaphes in letter of Apr, 8, 1816, to Adams (L. & B., XJV, 468-469). See also,

Jefferson already knew a member of the French Academy in the person of the Marquis de Chastellux, whom he had entertained at Mon-ticello. Through John Adams, he became friends with the three abbes, Mably, Chalut, and Arnoux — though the eldest of these, Mably, a writer of some note, died that summer (1785). Lafayette opened many doors for Jefferson, including that of his aunt, Madame de Tesse, though the Marquis was not much in Paris until the autumn of 1785. Perhaps it was through him that Jefferson met the Due de la Rochefoucauld, who was almost exactly his age and had a like passion for the physical sciences, along with a deep concern for the freedom and happiness of man. The "curious" Virginian could not have failed to admire the cabinet of minerals which the Duke kept on the second floor of the Hotel de la Rochefoucauld and he must have seen there the Marquis de Condorcet, who of all the philosophes was probably the most like him in spirit and temperament. These friends — Lafayette, La Rochefoucauld, and Condorcet — constituted for him the triumvirate of liberal aristocrats throughout his stay in France. He and William Short soon began to visit the chateau of the Duke's mother, the old Duchess d'Anville: La Roche-Guy on, on the borders of Normandy, where the liberals and savants also assembled. Short kept his eyes mostly on the young Duchess, Alexandrine, familiarly known as Rosalie, who was the Duke's niece and incredibly young to be his wife, but Short's friendship with her was only in the bud as yet. 35

Jefferson had various letters of introduction, whether he needed them or not, and Franklin was certainly a natural link between him and the world of letters and philosophy. The story of the latter's most spectacular meeting with Voltaire was still current; in 1778 the two men had embraced publicly in the French manner at the Academy of Sciences, kissing each other on both cheeks to the delight of the assembled savants. The recognized high priest of philosophy after the passing of Voltaire, Franklin might have been expected to introduce the apostle of enlightenment from Virginia into the innermost circles. Probably there was little opportunity to do this during Jefferson's first winter, when both of them were so much confined, but before Franklin finally left Passy in the summer of 1785, in a litter furnished by the King, he

Aug. 1, 1816 (ibid., XV, 48); and Adams to TJ, Mar. 2, May 6, 1816 (Works, X, 213, 218). Jefferson met Grimm during his first winter in Paris.