14. SAM

Matsuyama, 1945–1948

“Lollipop,” I repeated, too shocked to do anything but comply with the order, not really processing how casually it had been delivered. What am I supposed to do? Two weeks ago, I was Lieutenant Senior Grade Imagawa of the Imperial Japanese Navy. And here I am standing in front of an American officer—a superior officer.

“Fine,” said the Colonel, “report for work tomorrow morning at eight a.m.” He turned around to talk to the sergeant who was standing behind him holding papers.

As I began to sputter, “But,” Yamamura-sensei elbowed me. “Yes, Sir,” I said as my teacher turned and led me back into the hallway.

“Let’s go,” said Yamamura-sensei. “We’ll stop at my house before I take you home.”

Sensei had shown up late that morning on his motorcycle, as positive as ever. I heard the engine sputtering and grinding long before I could see who it was. I went and stood outside the house, wondering if it could be him and was very pleased when he rolled up.

“Imagawa, welcome back! I’m so glad you’re home alive. I asked around in Yanai-machi, and some of your neighbors there said your family was out here at Ishii again. I’m lucky today to have enough fuel to come out here.”

“Welcome, Sensei,” said Mother, who had come to the entrance from the kitchen, “it is wonderful to see you again. It’s certainly been quite some time, hasn’t it?”

“Ah, Mrs. Imagawa, you’re fortunate to have your son back,” said Yamamura-sensei.

Where was talk of the war, talk of Japan’s failure, and talk of how I was back only because I somehow hadn’t been able to do my duty? Why weren’t my elders and those near and dear to me saying anything about what had kept me awake at night and fretting through the beautiful autumn days?

“When I heard you were here, Mrs. Imagawa, I of course wanted to see Isamu,” he said, “but I must also confess that I thought that coming out here would give me a chance to ask if you or your neighbors have any extra food. It’s quite difficult finding much in the city. My wife has been doing a tremendous job making do, but.…”

“Oh, Sensei,” said Mother, “I’m afraid we don’t have anything to spare ourselves, but let me go ask some of the neighbors.” As she ran off, she called over her shoulder, “Isamu, don’t forget your manners. Ask Sensei in and make him comfortable. I’ll be back as soon as I can.”

Yamamura-sensei and I did just that, sitting at the table, drinking tea. We hadn’t seen each other for two years. He had news of my Matsuchu classmates. I heard with sorrow the names of my classmates who were dead: Suzuki, Mitsui, Yanagibachi, as well as Sakuragi, who was the bugler in the class behind mine.

“Yes,” he said, “there has been much too much death, Isamu, and we are going to have to live with this sorrow for the rest of our lives. For the young ones like you who were lucky enough to survive, there’s a great deal of work to be done to assure a different future.”

I was wondering how to say that the future was the one thing I couldn’t imagine when we heard the door open and Mother’s wooden sandals clattering in the genkan. She rushed into the room where we were sitting, her face flushed, and her apron filled with wrinkled sweet potatoes.

“Our neighbor, Farmer Morita had these extras, Sensei,” she said. “I brought as many as I could carry for you. It’s not much, but.…”

“Mrs. Imagawa, that’s not at all the case. It’s sheer delight to see such abundance. I’m sure that my wife can feed the family for weeks. My deepest thanks.”

As Mother knelt and began wrapping the sweet potatoes in a furoshiki, Yamamura-sensei said, “Mrs. Imagawa, can I impose on your further and borrow Isamu for the afternoon?”

“Of course, Sensei,” said Mother. “If there’s anything he can do to help you, please—”

“Well, I’d like him to come into the city with me. He can hold the sweet potatoes. I want to be sure to get this precious cargo back in good order. And I’ll take him to Yanai-machi. He hasn’t seen the changes in the neighborhood.”

Mother insisted that Yamamura-sensei stay for lunch. She had prepared my lunch and hers when she packed Father’s lunch box early in the morning. I’m not sure how she stretched what she had for the two of us, but we had a good lunch. Yamamura-sensei told Mother stories about his Matsuchu music students. It was fascinating to hear the familiar stories from the teacher’s point of view.

“Well, Mrs. Imagawa, I’m sure you never suspected how much behind-the-scenes comedy there was as we prepared for those glorious parades of the troops to the station,” he said, as he finished the last of his rice.

“I still remember the first parade we saw when we arrived home from San Francisco,” said Mother, “and how proud I was the first time Isamu marched as a musician in one himself.”

“And I will always remember how heavy my heart was last year when we accompanied the last group to the station. I thought of how many of my students I had seen off. Of course, we didn’t know at the time that it was the last group, but everything did get smaller and smaller and harder and harder, didn’t it?”

Mother smiled and bowed. Sensei suddenly became his energetic self again. Jumping up, he said, “Well, off we go. I’ll get him back before nightfall, Mrs. Imagawa. Thank you again for your hospitality and for these wonderful sweet potatoes.”

I had been on Sensei’s old scooter years before, but his new motorcycle was bigger and much older; the fifteen-minute ride into the city on the rackety bike was harrowing. While I was wondering if the sweet potatoes and I would survive, I was also steeling myself for the sad sight of the wide street and the empty space where the Yanai-machi house had stood. I had thought about it often in the last year and remembered staring at the dull gray of the Japan Sea on the long train trip from the north, wondering what home would be like with Yanai-machi obliterated.

When Yamamura-sensei stopped and I stepped off the motorcycle, it was worse, much worse than I had imagined. The house was gone; the street was unnaturally wide—about three or four times what it had been, and the new ugly street slashed diagonally through the neighborhood. It wasn’t just our house that was gone—all our neighbors’ houses were gone too. My eleven years there had vanished without a trace. The past was gone, the future still unimaginable.

“Had enough of this?” asked Yamamura-sensei. “Let’s go. I have one more place I need to take you.”

Rather than heading for his house, he turned the bike and headed in the opposite direction. “Where are we going?” I asked.

“You’ll see,” he yelled over his shoulder. I soon concluded that we were headed for Bancho Elementary School, but he stopped in front of the Ehime Prefectural Library building opposite the school and down the street from the house where the Grahams had lived.

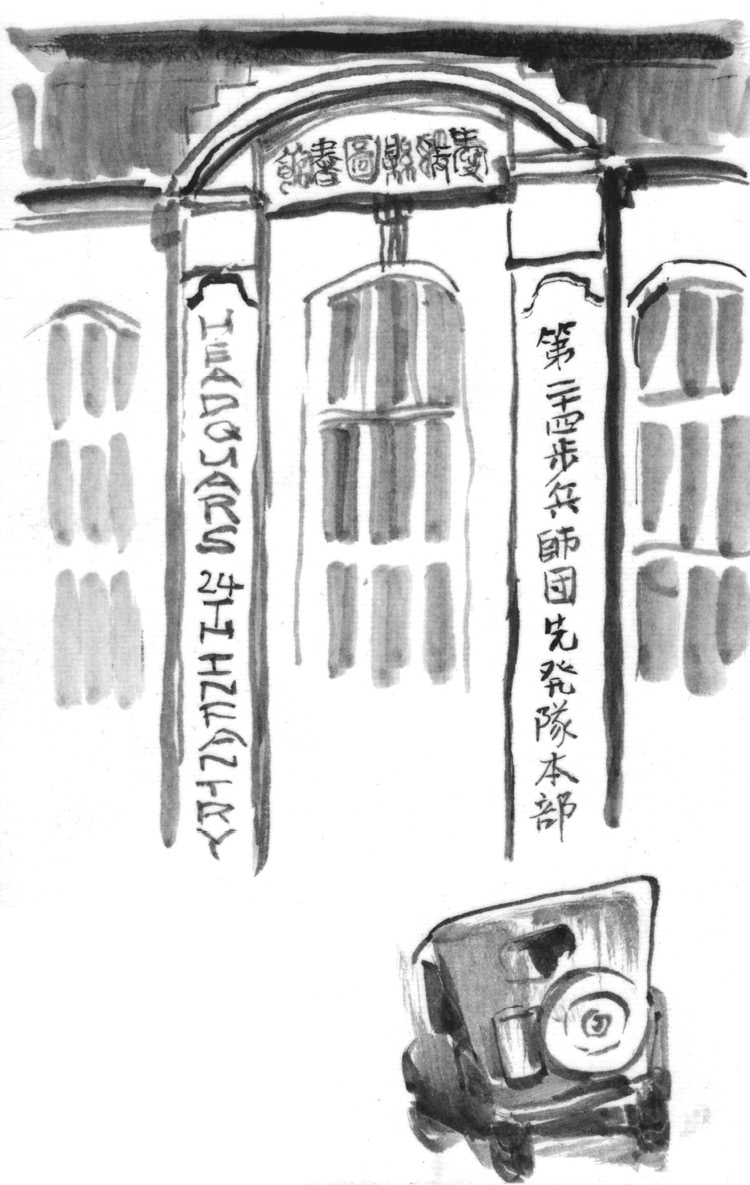

With his usual confident walk, Sensei started toward the Library. “Sensei,” I called, wondering if he didn’t see the big sign in English and Japanese that now hung above the entrance, HEADQUARTERS, ADVANCE PARTY, 24TH INFANTRY.

“Come on, come on, don’t dawdle, Isamu,” he called. “They won’t hurt you.”

He was my teacher. I had to do as he said.

Once we were inside, Yamamura-sensei headed straight for the first room with an open door. I was scrambling to keep up with him. There was a uniformed American sitting behind the desk.

“Good afternoon, Colonel,” said Yamamura-sensei in his lovely, precise English. “This young man was born in San Francisco and can speak English. His name is Isamu Imagawa.”

The officer looked from Yamamura-sensei to me. I stumbled sideways and took a step back. The scrutiny was excruciating. Time stretched as he sized me up. I was shocked when all he did was tell me to repeat the English word for a treat I remembered from San Francisco.

I entered the building with great trepidation. There was no Sensei to push me along. Only my sense of duty, my obligation of obedience. But I was obeying reluctantly. Why should I work for people I had fought against only a month before? What could Yamamura-sensei possibly have been thinking?

My fear was almost immediately replaced with surprise and then, eventually, with curiosity about what my future could hold.

And it was that morning that my future began. Those who survived the kamikaze corps and wrote their memoirs all focused on their wartime experiences—as well they should. The Great Pacific War, as it is called in Japanese, was the defining event for those my age—on both sides of the Pacific as well as in Europe. We came of age with our military service and what we experienced during the war shaped our characters for the rest of our lives, even if most of us rarely, if ever, talked about it. But for me, my dual background, my roots in both my Mother and Father Countries, and my English language abilities also changed and shaped my life after the war. I had joy and sorrow, satisfaction and disappointment, struggle and triumph, with the good always outweighing the bad. To complete my story I have to and want to write about my life after the war—the life that began that day—a life that gave me the chance to do some good, and, even though this is a rather grandiose sentiment that I’d never express aloud, a chance to promote international understanding and peace. It has also been a life I’ve shared with my beloved wife. It is a story I want to write. I’ve known for almost two decades that I should tell my story. And now I’m finally fulfilling that promise to myself.

It was in Ohio that I first decided I had to put pen to paper.

I think there was so much press fuss because the student reporter’s article about the “Kamikaze Professor” was published in December 1978 just a few weeks after the news of the mass suicide in Guyana. I don’t know who was more surprised, me or the young girl my colleague Lloyd had sent over from the journalism school for a practice interview. With the camera crews and the wire service reports, we both had our full fifteen minutes. Interesting, and even a bit entertaining.

Memories of the war were already sketchy then, so now in 1994, almost another twenty years later, I’m glad I’m putting the whole story of “the American Kamikaze” down on paper. Americans have never had any clue about these kinds of things, and now, having been back in Japan for so many years, I see knowledge of the war fading away here. The young people are now like the Americans I taught for twenty years. It’s not just a matter of knowing more about computers and anime than abacuses and shamisen. They don’t understand how we let ourselves be led into a ruinous and doomed misadventure, nor do they remember or mourn the dead or regret the folly that took so many young lives.

My dearest Akiko thinks that I don’t realize it, but I know time is short. I keep up my part of our charade by demanding the second glass of scotch and pestering her for fried chicken as if I didn’t know what the doctors think—and what I’m sure they’ve told her. One of the sweet secrets of a long-married couple: what we pretend we don’t know. Like how relieved she is that we ended up here in this small city with the beautiful castle rather than “home” in Matsuyama. I still can’t help myself—sometimes I still talk about it—all those places of my childhood still call me, just as the even earlier places in San Francisco’s Japantown still call too.

I started writing in English because the Mother Country tongue comes easier, especially because I started at the beginning, with San Francisco. Next year the Father Country will take over and I’ll translate into Japanese.

I haven’t done any serious research—it’s been enough to look through my own materials and leaf through a few books over the last months. I’m sure I’ll misremember some of the details and horrify any historian who may read my memoir. But I have my photographs—from San Francisco, from Matsuyama, and even the ones from the bases at Mie, Izumi, Wonson, Haneda, and Chitose that we were supposed to burn. The pictures have helped me remember so much that what I’ve forgotten won’t matter.

I only have one goal. It is my hope that my story will help others realize that what they strongly believe in at one point in life, even to the point that they’re willing to sacrifice their lives for it, may ring completely hollow in later life. No disagreements, no differences of opinion—political, economic, social, religious, or otherwise—are worth the sacrifice of human life, including one’s own. If this message gets through, I will have succeeded. Writing my story will be worth it.

The Colonel was in the center hallway outside his office and saw me as soon as I came through the front entrance. He was obviously on his way somewhere, but stopped and said, “Good morning, Mr. Imagawa.” Turning back to his office, he called, “Sergeant, take this gentleman to the Translation Section and introduce him to Lieutenant Elmenhall.” Turning again and looking at me, he said, “Good luck. Do well,” and went off down the hall.

The sergeant I had seen the day before came into the hall and said, “Come with me.” I climbed the steps behind him. Gentleman? The enemy is referring to me as a gentleman? How can that be?

The sergeant led me into a high-ceilinged room, where I saw a tall man with sandy hair, a sprinkling of freckles, and greenish-blue eyes. At first glance he reminded me of Morgan, and I realized that I hadn’t thought of my friend for years. Had he lived to have post-war experiences as strange as what I was experiencing that morning?

“Sir, here’s the new translator,” said the sergeant, saluting before he turned to go back downstairs. The tall fellow looked me over and smiled.

“I understand you’ve passed the Colonel’s famous English proficiency test,” he said. “So you can obviously manage my name. I’m Lieutenant Gregory Elmenhall, and I run this section.”

“Yes, Sir,” I said. The office was reassuring. It looked orderly and the four Japanese working at the desks looked fine. Okay. This tall American is going to be my boss.

With great kindness Lieutenant Elmenhall explained that I was to join four others and work at translating Japanese newspaper articles into English. Lieutenant Elmenhall told me we would sometimes have to work as interpreters as well. The others were American-born nisei just like me, but I had never met any of them before. The two I remember best were the Sawada twins—Carol and Louise.

The Americans were serious about their work, but very casual in their interactions. Almost immediately I was Sam again to everyone. After the first week, I lost both my impulse to salute and my horror that I was inclined to salute Americans, the enemy. Every so often I still bristled inwardly at taking orders from an enlisted man younger than myself, but slowly, slowly I recovered a civilian mentality.

I came to realize that the Americans were the people I remembered from my childhood, not the devilish barbarians that had been the staples of the wartime propaganda. All that rhetoric, all that ugliness, had vanished like spring snow. It disappeared, of course, because of the Occupation. But it wasn’t just me—my colleagues had come to terms with the Americans, and slowly, and sometimes in small bursts of joy, people began to relax. But there were long-term effects of the rhetoric of the war—we weren’t left with memories of beautiful spring snow. No, even as we began to rediscover joy, we Japanese were left with shame and confusion and having to live with the knowledge that we had wholeheartedly participated in the folly of the war.

I plunged into the work. It was good to have something to do, and I enjoyed it a great deal. Like the others, I found the official documents troublesome. We often pored over our dictionaries. I was shocked at how rusty my English had become. For the two years I was in the military, I neither spoke nor read a word of English. And my command of English had always been colloquial, the language of a kid in San Francisco. I did a lot of studying in my hours away from the office, teaching myself the terminology for civil engineering, plant pathology, and medicine. It took a while, but eventually I mastered the bureaucratic jargon and was happy to learn a bit of substance in a number of different areas.

In October, the entire 24th Infantry moved into Matsuyama. Its nickname, the Taro Leaf Division, was a tribute to its home base of Hawaii. The U.S. soldiers camped on the grounds of the former Matsuyama Naval Air Base, set up checkpoints, and dispatched patrols all over Shikoku Island. All the activity caused a fair amount of local consternation, but it didn’t take long for everyone to reach the same conclusion that Yamamura-sensei had known, instinctively, was correct and that I had come to in my month of working for the Occupation—they were not going to do us any harm.

Like Yamamura-sensei, Father came to this conclusion early. After my trip to the city with Sensei, he brought me back to Ishii and dropped me off with a cheery wave to Mother and shouted, “Thanks again for the sweet potatoes. My wife loved them when we dropped them off. Isamu has some interesting news for you.”

When Father arrived home from work, Mother and I were anxiously discussing the afternoon’s events. After he listened to the lollipop story, Father laughed, and said, “Son, I think it’ll be fine. You’ll be a natural. And you need to stop moping around the house. Time to move forward.”

I watched Mother swallow her worries and decide to agree with Father. The next thing she said was, “A bit of chicken and some sweet potatoes,” in response to Father’s inquiry about dinner.

He laughed again, “Ah, the infamous trouble-making sweet potatoes. I’m looking forward to an interesting chat with Yamamura-sensei the next time I see him. I think, Isamu, that I should thank him. I know you don’t think that’s appropriate, but I have a little bet with myself that you will eventually.” Turning to Mother, he said, “Let’s have a taste of those sweet potatoes, and I do believe we still have a bit of shochu in the back of the kitchen cupboard, dear. Let’s drink a toast to our son’s new work.”

Late one night I arrived home after interpreting during a meeting of the civic officials in Tobe with the Division representative; the trip from the far suburb had taken much longer than I expected. I found Mother and Father laughing at the table, waiting for me before starting dinner. They looked lighthearted and younger than they had in a long while. “Isamu, come listen to the funny story your father has to tell you.”

“Yes, my son the translator should be proud of me,” said Father as he made space for me at the table. “I got home early from work today and decided to do a little weeding in the vegetable garden. And from there I went to see Farmer Morita. I was walking back along the road. I still had my hoe with me—but mind you, no sweet potatoes,” he laughed. “I must have looked the complete country bumpkin. I went past an American soldier—Isamu, he was no more than eighteen—a baby compared even to you—who was standing sentry at the checkpoint. I did the polite Japanese thing and smiled.

“When the soldier saw, me he said—in English of course—‘Hi there, old man. How are you today?’”

“‘Well, I’m just fine thank you,’ I replied. ‘How are you?’”

“‘Did you just speak English?’ he said. I don’t think he could believe his ears. I guess English-speaking old Japanese farmers weren’t what this kid was expecting. So I stopped and explained why I knew English. He was from Pennsylvania, and San Francisco is, I think, as unimaginable to him as I’m sure Matsuyama was just a few weeks ago. It was a pleasant chat. I wish you could have been there.”

Not only were they not going to do us any harm, they were determined to improve things. A few weeks after all the excitement of the full occupation—and after the patrols had become nominal at best, small teams of U.S. Army personnel moved into the capital cities of all four of Shikoku’s prefectures.

The Ehime Prefecture Military Government Team (MGT) was stationed in Matsuyama. The MGT took over civil administration from the Division, and the translators were reassigned to the team. And soon thereafter the entire Division moved off Shikoku and set up operations in Okayama. The teams were then the only military presence. In each prefecture, the teams were divided into four administrative functions: a Civil Information and Education Section (CI&E), an Economic and Labor Section, a Legal and Government Section, and a Medical and Social Section. I was assigned to the CI&E Section, and with the new assignment, I moved to an office on the fourth floor of the Prefectural Library building. I found it ironic that CI&E was occupying this space.

The large room where we were working had been a ceremonial space, and it was there that the Prefectural Governor had bowed to the Imperial portraits before and after he read official decrees, including the one that supplemented the Emperor’s speech and formally ended the war. The portraits were still there. Looking at them the first day I worked in that room, I remembered my first experience with Japanese official ceremonies and remembered how alien and fascinating it all had been to the out-of-place little American gentlemen with his neat suit and long hair.

All of us translators started our new assignments with considerably more confidence than we had had in our first days working for the Division. And at this time my life began to shift—inexorably, I now realize—toward English. I was using my English every day. Of course, everyone in Ishii Village knew where I was working and what I was doing. And now everyone remembered that Mother and Father had lived in San Francisco, that I was born there, and that I still spoke English.

First two, then four of the Ishii Village children knocked on our door and asked about English lessons. Soon I lost track of how many had asked, and I was teaching free classes two nights a week. Mother joked about her son following in Yamamura-sensei’s footsteps, and Father sometimes poked his head in and helped me demonstrate simple phrases. The children sometimes brought little offerings—vegetables, some rice or barley, a piece of cloth, some charcoal. Mother and Father would make sure that they sorted these things out, and redistributed any extras we had to neighbors with too many mouths to feed.

My new job at CI&E was to travel as a translator-interpreter throughout the prefecture with Captain Roger Rudolph. Our job was to make sure that local schools were complying with the educational directives from General Headquarters (GHQ) in Tokyo that were promulgated through the Ministry of Education. The specifics of this mandate included checking to be sure that the new textbooks were in use and that there were no remnants of the old imperialistic, militaristic slant that had dominated education during the war.

CI&E also had the duty of checking to be sure that no weapons were stored in the schools or hidden on their grounds—it had been common in the last months of the war to bury caches of weapons for use during the final battle the government expected on the homeland. The plan was to distribute them to all civilians when the fateful day arrived. All weapons should have been surrendered to the Americans during the first days of the occupation, but rumors circulated about caches that were still hidden. Given how peaceful everything had quickly become, I found it hard to take this seriously, but it was still, officially, part of the job.

Captain Rudolph and I got along well, and I became quite fond of Roger, as I believe he did of me. We started with the schools in Matsuyama, which were all relatively large. We then progressed to the suburbs, like Tobe. Finally all that was left were the schools in the remote villages at the far reaches of the prefecture. We went by jeep. Captain Rudolph drove and I was the passenger. In the out-of-the-way places, the small fishing villages or the farming towns way up in the mountain valleys, our arrival invariably caused a great stir. Captain Rudolph’s large body, big round eyes and—as we say in Japanese—his “high” nose, made him scary to the folks in these isolated places. Many of them had never actually seen any foreigners, but he fit the image of the “foreign devil” they had been told about endlessly during the war.

Not surprisingly, we often got lost on these excursions. On several occasions, we would see villagers far ahead on the road and were relieved that there would be someone to ask for directions. But by the time the jeep reached the place where we had seen them, they would have disappeared, scampering into hiding, like children playing hide and seek. After this happened a few times, we figured out how to deal with it. Roger would drop me off and drive on ahead. I would stand in the road and wait until the villagers felt safe enough to come out of hiding. Once they were convinced that we were there only to visit the school, they were happy to give directions.

Our reception at the schools was an entirely different matter. Usually the children ran out of their classrooms as soon as the jeep pulled up. They kids were full of curiosity and somehow convinced that this big funny-looking foreigner would have treats. As they surrounded the jeep, the teachers stood sheepishly in the background. Our usual drill was to send everyone back to the classrooms. Captain Rudolph would meet with the principal in his office and then tour the school, being introduced to each teacher, asking the questions, and making the inspections he was there for in the most casual way imaginable. We virtually never found anything out of line. At the end of his tour, he would ask the teachers to assemble the students in the playground. By now, the teachers were able to reassert control, and they lined the students up neatly. And this was where Captain Rudolph always had the most fun. He did indeed have treats, usually candy and sometimes small notepads or supplies of pencils. Discipline was destroyed again as he distributed the candy to the children, who were usually literally jumping with joy. The teachers were always especially grateful for the supplies, and they would be bowing deeply as we left, as the children ran alongside the jeep, begging for even more candy, and yelling a chorus of “Hallo! Good-bye!” or whatever other tiny scraps of English they knew.

Only one of our excursions had no lighthearted elements at all. CI&E received an anonymous letter saying that army rifles were buried in the sandbox in the playground of a junior high school in the suburbs. Captain Rudolph and I went to the school to investigate. The principal met us at the entrance, pale as a ghost. He had clearly ordered that the students be kept indoors and seemed to know exactly why we were there; when we asked him to have the school custodian dig up the sandbox, he began trembling. “But, Sir,” he said, “there were some rifles there, and they might still be there. The neighborhood association folks came the week the war ended. They didn’t really ask. They just buried the box. But they were just wooden dummy rifles. They were used when they held the training sessions for all the civilians in this area here in this playground.”

“Well, let’s see,” said Captain Rudolph. “Please call the custodian.”

The principal was still agitated, but he walked off and came back with the custodian, who had a shovel over his shoulder. As the custodian went to work digging, the principal stood by the side of the sandbox. He nervously pushed his hair back from his forehead, and then reached in his pocket. He must have been looking for a handkerchief, but didn’t seen to have one. He finally used his hands to wipe the perspiration from his forehead. When he finished, he didn’t seem to know what to do with his hands, and eventually starting wringing them. I had never seen anyone do that—I learned that day that people actually do that under stress; it’s not just a dramatic detail added to stories. Every time Captain Rudolph said something to me in English, the principal looked even more anxious. I really wanted to say something to him, but there was nothing for me to translate, and I knew that anything I’d say would be improper interference.

The custodian grunted when his shovel thudded against something. Captain Rudolph and I helped him push off the last of the sand from the top of the box and wrestle it out. We lifted it out of the sandbox and stepped back as Roger leaned over and opened the latch. The principal stood behind him, still wringing his hands. About twenty wooden rifles were shoved every which way into the box. Roger and I upended the box and dumped them—just to make sure they were all just dummies. As we bent over them, Captain Rudolph looked over his shoulder at the principal. “Well, Sir, you were absolutely correct. Thanks for letting us take a look.” Even before I could translate, the principal was sagging with relief.

He hung his head as he apologized and thanked Captain Rudolph for being so understanding. As he spoke, the custodian started quickly dumping the wooden rifles back into the box. He finished as Captain Rudolph and I were walking back to the jeep. My last memory of this episode was hearing the custodian ask the principal, “So what should I do with these damn things now? Bury them again?”

I got married on December 14, just four months after the war ended. The bride? Kayoko, of course; the wedding was the culmination of the omiai meeting the year before. Mother started pushing the arrangements to their final, unavoidable conclusion the week after I arrived home.

I had the day off from work. Mother, Father, and I walked to Ishii Station, took the train to Matsuyama City Station, where we changed trains and headed to a small town called Gunchu out in the far suburbs on the other side of the city. As I walked through Matsuyama City Station with my parents, all of us dressed in the best outfits we could patch together from our sparse wardrobes, I imagined myself slipping away. I thought about how quickly I could be at the office, doing my interesting work in English. Somehow, Mother and Father wouldn’t notice and wouldn’t care.

Mother chose Gunchu for the wedding because that was where her younger brother, a successful doctor, lived. His house was large, the rooms spacious. When we arrived the Shinto priest was already there, waiting rather impatiently. The wedding began almost immediately. The bride entered, in full traditional Japanese wedding dress. Looking at her, all I could think was that she was not my type at all. The ceremony was soon over, and the priest, with his cash envelope from my uncle discreetly pocketed, was on his way. The twenty or so guests—all close relatives of my family and Kayoko’s—sat in the spacious tatami room chatting. I sat with them, but had nothing to say.

Kayoko went off with her mother to change. When she reappeared, she was wearing an obviously high quality Western-style dress. As she walked back into the room, I thought this outfit’s no improvement. She absolutely is not my type. The entire wedding party then walked to a local inn for dinner. It was a feast—the best food I had had in years. After dinner, everyone left, but Kayoko and I stayed the night at the inn. The next morning, I awoke, and lay still as she slept. I tried to think, to reason myself into accepting my marriage to the woman beside me, but I couldn’t get very far because I was overwhelmed by the knowledge deep in my being that Kayoko was not my type.

The two of us took the train trip back to Ishii Village. I provided the only conversation, announcing the travel directions, “We’ll stay on this train for six stops.”…“The next stop will be Matsuyama City Station. We’ll change trains there.”…“Now we’re at Ishii Station. It will only take ten minutes to walk home.”

It was with great relief that I crossed the threshold into our Ishii Village house and called, “Mother, we’re back,” and with even greater relief that I left for work as soon as we all finished the lunch that Mother had prepared.

Only Mother had talked during lunch, chattering on and on about how well everyone looked at the wedding, how nicely everyone had managed to dress, how kind her brother had been to lend his house for the ceremony, when would be the best time to go to Ishii Town Hall to record the wedding in our family register, how nice the plates and bowls were that the inn used in the place settings for our lunch, how delicious the food had been, how our lunch was so poor in comparison, but at least we had some delicious local sweet potatoes from our neighbor and tenant farmer Morita. “Have Isamu tell you why sweet potatoes are such a big joke in this household,” she said to Kayoko. “And of course he’ll tell you all about that dear man Yamamura-sensei, the teacher at Matsuchu.” Kayoko gave her usual response: Nothing!

Finally, even Mother seemed to give up and said, “Kayoko, dear, let’s clear these lunch dishes and get them washed. I want to make sure you know how the kitchen is laid out and where everything is stored.” I made my escape.

When I got to the Prefectural Library, a peaceful early afternoon quiet filled the wide entrance corridor, and I didn’t meet anyone as I climbed the wide stairs to the fourth floor. I savored being truly by myself for a few moments and inhaled the kerosene fumes from the heaters and the familiar wintertime wet wool smell. The kettle was bubbling on the top of the heater when I walked into our big work space on the fourth floor. Carol and Louise were eating their lunches at their desks. Everyone else had disappeared. “You missed everyone, and so did we,” said Louise. “When we got back late from going with the Colonel to see that visiting general off at the station, everyone else was gone. There was a last-minute translation job at the Regiment. I think the schedules were confused because everyone was busy thinking about the general.”

“Congratulations,” said Carol. “Welcome back.”

“Yes,” said Louise, “we’re very happy for you.”

“I guess,” I said, hoping I didn’t sound as ungrateful as I felt, and added, “Thanks a lot, actually,” in English, because we all liked using the easy, casual phrases of our childhood. I then switched back, into work mode, “Is there anything for me to do?”

Carol laughed and said, “The Captain has a big report on his desk from the Education Ministry. He said he wanted it summarized and that whoever had the most free time should start the project. Isn’t that you, Sam?”

“Yes, today that’s me, most assuredly,” I said, as I picked up the report. This dull work would be fine for the afternoon. The first afternoon that my mother and my wife, my wife, were at home, getting to know each other. I turned to the statistics on textbook inventory.

Captain Rudolph left the next week. “If I’m lucky, I’ll catch the right flights that will get me home to Seattle by Christmas Eve. My first order of business after hugging my mom and dad is proposing to Evelyn. I hope she’ll still have me. I hope to have the same sort of happiness in front of me that you have now that you’re married, Sam. All the best of luck to you,” he said. “I wish you well in everything that lies before you.”

I had heard a lot of stories about Evelyn, a grade school teacher, as we drove around looking for those country schools. I imagined the tinsel shining on a Christmas tree in the living room of his parents’ home and pictured Roger and Evelyn sitting with his parents, opening presents, and admiring the ring shining on her finger. I wondered if he thought it was odd that I had never spoken to him about Kayoko. My wife.

“I’m so grateful for all you’ve taught me. I wish you a safe trip and a long and happy life with Evelyn. Take care of yourself, Roger.”

By this point, although I was a little surprised at myself for using his first name to his face, I wasn’t at all surprised at my impulse to do so. I was comfortable with the Americans, happy to be speaking English so much, my mother tongue, as I was now thinking of it, and taking pleasure and a sense of accomplishment from my work. I had begun reading everything I could get my hands on about language teaching.

Roger’s successor was John Bolunkly, a civilian on temporary assignment. I did the same job with him, but his style was even more casual than Roger’s. After a few months, he was replaced by Bill Scott, another civilian. Bill was a little less than a year younger than I was. He had majored in psychology and joined the Navy immediately upon graduation. The Navy sent him to its language program in Boulder. His Japanese was already fluent when he arrived in Matsuyama, and got better with each passing day. So my job was much easier—except when it was harder. Because Bill wanted what he said in public officially to be flawless, he still had me translate. Occasionally, after I finished, he would look at me, give me his special wry smile, and say, as quickly as he could so no one else would understand, “Hey, Sam, that’s not what I said.”

I spent a fair amount of time studying up on the educational terminology we worked with every day. And I continued to read as much as I could on language training. Bill was very helpful. He shared everything he had learned from the Navy, made sure I knew about everything published by the Occupation on language education, and lent me all of his books. I still have some books on language pedagogy that he had his sister send us from Berkeley, where she was studying. Working with Bill, I was sure that I had found my life’s work. Teaching language was, for me, challenging and thrilling. Watching my students realize that they were not just memorizing dull formulas and phrases, but acquiring and mastering the skills to actually communicate with other humans, was a great joy. Giving them the confidence to do well was my challenge.

With Bill, I also worked on the comprehensive reorganization of the Japanese education system. The work we began that year, under the direction of General HQ in Tokyo, became part of the complete reform of the system that went into effect in 1948. Japan adopted an American-style system of six years elementary school, three years junior high school, and three years high school, followed by four years of higher education. New school buildings were built all over the country; textbooks were completely rewritten. English became an elective starting at the junior high level. It was a time of change, creativity, and a certain amount of turmoil. I loved it.

It was about the time that Bill arrived that things changed at home. I arrived home from work one night and was surprised to find Mother was waiting in the genkan. She took my arm and walked me up and down the road in front of the house. “Isamu, darling,” she said, “I have the most wonderful news.”

The whole situation had me unsettled. Mother’s obvious excitement was making me apprehensive. “Yes,” I said hesitantly.

“It’s Kayoko. She’s pregnant. It’s such wonderful news for our family.”

I was searching for the appropriate response when she continued, “I guessed. She wasn’t ready to tell you—or anyone—and she is very nervous and worried, but it’s such wonderful news. Everything will be fine. She’ll start feeling better soon, and then she’ll look forward to the baby as much as I’m looking forward to being a grandmother.”

By the time we walked back into the house, I realized that Mother was right. I was thrilled at the prospect of a son. Mother and Father joined in my excitement, but Kayoko was adamant. When we were alone she stubbornly insisted that she wanted an abortion. “There’s not enough room in this Ishii house,” she said. “How am I supposed to raise a child here? There are only two rooms plus that antiquated kitchen. I won’t do it.”

The topic was still under unpleasant discussion when I got an urgent call at work one afternoon. Mother was calling from an obstetrician’s office downtown, and told me that Kayoko had had a miscarriage. Mother found her bleeding and in great pain that morning. Mother’s nursing skills and her resourcefulness were both on display that day. She took care of Kayoko and wangled a ride into town from the only neighbor who owned a car. When Mother brought her home, Kayoko was even quieter than usual. I sometimes wondered what went on in her head, but there was no way for me to know or to figure out what had really happened. Her only topic of conversation was the impossibility of our living conditions; it was all she ever talked to me about.

Events far beyond our control were pushing us in directions we could never have anticipated. Land reform was Kayoko’s unexpected salvation. The new Agriculture Reform Laws required absentee landlords to surrender their lands to the new agricultural cooperatives, so Father was forced to sell the lands he owned to the Ishii Village tenants. The proceeds were just enough to finance a new house in town. It was our final farewell to Ishii. For many years I would mourn the loss of the old house with the thatched roof, the soft, warm tatami, the vegetable garden, the fields, and the stream. My life was to be in cities, but memories of the sweet country ways of Ishii were always with me.

Father and I went to see my friend Maki, who was in the construction business. We arranged for a new Yanai-machi house to be built. Maki assured us that our plot there, where reconstruction was now allowed, could accommodate a two-story house. He went to work, and about six months later we all moved into our new home. There were four tatami rooms, a dining room, a study, a bath, and a large kitchen where the two housewives could work together.

But part of Ishii came with us to the city. The children I had been teaching were not going to be deterred just because I was moving away. Nor were they deterred when I told them I had to start charging. They were willing to travel almost a half-hour by bike into the city for their lessons, and they were willing to pay. So my evening classes after my days at Ehime MGT continued, two sessions an evening, three evenings a week. The extra income was good as we pieced together a new life in the city. I had no idea at the time that this was probably the real beginning of my career, the beginning of work I would do for half a century.

Bill Scott went home early in the summer of 1947. He had been accepted in a graduate program at the University of Michigan. As summer turned to fall, it made me smile to think of him crossing the campus kicking the autumn leaves, carrying his books, back to being a student. I knew he would be happy and successful. I wondered if he found anyone in Michigan to speak Japanese to.

Bill’s replacement was Captain Shirley Schneider. Captain Schneider was much older than I and a rather stern personality. When I learned that she had been a high school principal in Saint Louis before she joined the army, I was not surprised. It was the first time I had ever had a woman boss, and they were rare enough even in the U.S. military, but I found working for her and following her orders easy. She was an expert school administrator and made great contributions to education in Ehime and neighboring prefectures. The improvements she put into effect earned her my respect, and the respect, even though it was sometimes grudging, of all the local Japanese officials.

Once we had moved to Yanai-machi, things settled down at home. Kayoko seemed happier, but never said anything, one way or the other, to me. She and Mother grew even closer. I missed my own closeness to Mother, but I was so busy with work and with my nighttime teaching that I didn’t have much time to dwell on it. About this time, I found a book by Dr. Charles C. Fries of the University of Michigan entitled The Teaching and Learning of English as a Foreign Language. I was enthralled. Dr. Fries’ book supported many of the ideas I was developing on my own with my Ishii students. Persuading my students that learning English was the key to communication across cultures was easy to do at that point; watching the light in their eyes when one of my explanations made sense, when one of our drills gave them the confidence to speak to the Americans, was a great thrill for me, and Dr. Fries’ book made me, I believe, a better teacher. On the evenings when the students and I were working in the study, Mother or Kayoko would come in halfway through the lesson with a tray, a big tea kettle, and a supply of cups. Mother would say, in English, “Good evening, everyone,” and would sometimes add “Gambatte” in Japanese, and “Good luck with your studies,” in English. Kayoko would just put the kettle and the tea cups down on the table, smile slightly, and leave. She never asked a single question about English, about teaching, about my interests. And her attitude made it clear that she had no interest in studying herself.

Captain Schneider and I continued our work, and I had no idea of doing anything else. It was still interesting, and I was learning a great deal about education. However, one day early in 1948, officials of a school called Nitta Gakuen in the Matsuyama suburbs approached me. They were working on establishing a new institution to be called Matsuyama Junior College of Foreign Languages and invited me to join the faculty and teach English. I was flattered and interested in the job, but I told the officials that I couldn’t leave my job with MGT. They pressed. Finally, although I was sure the answer would be no, I promised to ask the U.S. military if they would let me take on the teaching as a second job. To my surprise, the answer was yes. Their theory was that the classroom work would make me a better translator-interpreter for educational matters. With this endorsement and with the confidence I took from Dr. Fries’s book, I began my work. My students at the Junior College were quite enthusiastic. My class was their first opportunity to learn spoken English. As I ran my students through drills and guided them through conversations, I often thought of Suzuki-sensei from Matsuchu and how thoroughly I had disgraced myself by embarrassing him. I looked back with the sympathy I had been too young and too naïve to have at the time.