2

![]()

Escaping Palmyra and Copying Characters from the Gold Plates

Just weeks after Joseph Smith retrieved the gold plates, rumors about them spread like wildfire in and around Palmyra. Most viewed the reports of the gold plates with skepticism, if not ridicule. Many, however, were deeply interested in finally making sense of the stories that had circulated. Some even hoped to see or hold the plates in order to judge their value or share in the profits they might generate. This interest quickly turned to harassment that lasted for weeks before Joseph and Emma Smith moved to Harmony, Pennsylvania, in December 1827.

Lucy Mack Smith recorded much of what happened during this period in her 1844 – 45 history. Her recollection for this period focuses on Martin and Lucy Harris, particularly the latter. It presents Lucy Harris as a person to whom God gave an undeniable witness of the plates, yet who dismissed the witness with little regard for its value. The problem with Lucy Smith’s account is that she was not fond of Lucy Harris and seems to paint her in the worst light possible, making it difficult to understand Lucy Harris’s real intentions. This same problem of negative bias is also apparent in the way Lucy Smith treats other figures in later chapters of her history. Nonetheless, statements from Martin Harris confirm some of the details in Lucy Smith’s history, and though we only have a negative view of Lucy Harris, Lucy Smith’s history develops Joseph Smith’s relationship with Martin Harris well during this period.

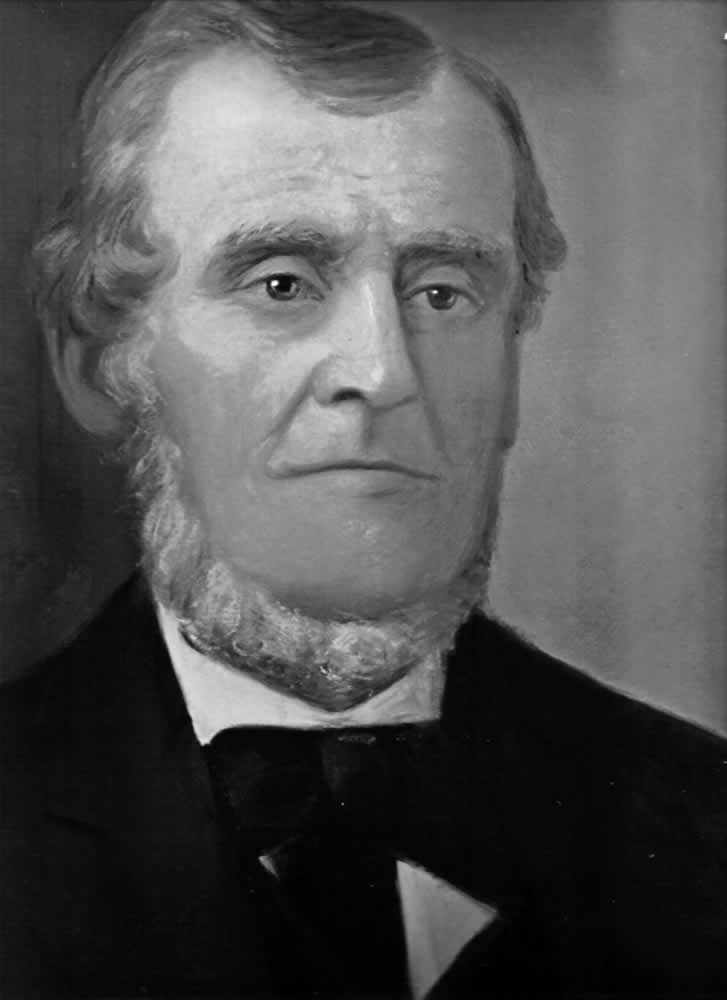

Portrait of Martin Harris. Painting by Lewis A. Ramsey.

Embracing an accurate view of the Harris family is extraordinarily important to the coming forth of the Book of Mormon. They became keenly interested in what Joseph Smith had unearthed that fall, which led to years of involvement in translating and publishing the Book of Mormon.1 Martin Harris’s brother Preserved had gone to the village and heard the rumors and stories of the plates, likely from some of the money diggers with whom Joseph had previously worked.2 Martin, who was in a position to help Joseph translate and find funding to print the Book of Mormon, knew the Smith family well and knew about Joseph’s visionary background.3

When Martin heard about the plates, presumably from his brother, he thought nothing of the matter, considering the stories to be just some of the many tales current among the various hired hands who had searched the hills and caves of Palmyra and Manchester for buried treasure. He thought that Joseph Smith and his fellow treasure seekers had likely uncovered an “old brass Kettle” rather than a set of ancient plates.4 Likely in early October, not long after he had heard about Joseph’s discovery, Martin visited Palmyra village and was asked by one intrigued resident what he thought about the rumors. According to Martin’s recollection, he was initially open to the idea that Joseph Smith had in fact retrieved gold plates from the local hill. Unknown to Martin at the time, Joseph had apparently already seen Martin in the spectacles and knew that God had chosen him to help bring forth the Book of Mormon.5 Possibly after hearing about Martin’s interest in the plates, Joseph Smith sent his mother, Lucy Mack Smith, to visit with Martin to find out if he would help Joseph translate the plates.

After traveling from the border of Manchester up through the town of Palmyra and across the Erie Canal, Lucy Smith arrived on the doorstep of Martin Harris’s house. Lucy Harris, Martin’s wife, answered the door. Joseph’s mother explained the purpose of her visit and recounted the details of the discovery of the plates “in order to satisfy” Lucy Harris’s curiosity.6 While Latter-day Saint literature often portrays Lucy Harris as an inveterate enemy of Joseph Smith and his claims to divine revelation, Lucy Mack Smith remembered that Lucy Harris was initially excited about the plates and eagerly discussed them with her visitor (admittedly, this may have been a way for Lucy Smith to emphasize Lucy Harris’s dismissal of the plates later). Lucy Smith remembered that Harris “did not wait for me to get through with my story” before responding by offering money to assist Joseph in his efforts to translate. Lucy Smith wrote, “She commenced urging me to receive a considerable amount of money which she had at her own command a kind of private purse which her husband permitted her to keep.” Lucy Harris’s sister also offered money during the same visit for the project, but Lucy Smith refused both offers, unwilling to commit herself to anything without Joseph’s approval. Lucy Harris persisted, however, and was “determined to assist in the business for she knew that he [Joseph] would want money and she could spare $200.” Despite the considerable offer, Lucy Smith again demurred and asked instead if Lucy Harris would kindly take her, as she had asked earlier, to visit with her husband, Martin.7

Lucy Mack Smith. Sketch by Fred Piercy. © Church History Museum.

At last, Lucy Harris guided Lucy Smith through the house to the fireplace, where Martin Harris was setting the bricks for a new hearth. When Lucy Smith approached the fireplace, Martin declared that he wanted to speak to Joseph and also explained that he would be leaving Palmyra for twelve months. He was desperately working to prepare his farm for his long absence, intending to have a hired hand care for his property while he was gone. Martin told Lucy Smith, “I [have] not time to spare,” but “[you] might talk with my wife [while you wait]” because, as he explained, he would not be finished until that evening.8 Once Harris completed his work, he finally met with Lucy Smith. Martin remembered her telling him that Joseph had brought “home the plates . . . and . . . that Joseph had sent her” to recruit his support. Harris explained that he had already planned to go to the Smiths’ Manchester home to meet with Joseph after hearing the rumors about the plates, but that he could not go at that time. Harris asked his son “to harness [his] horse and take her [Lucy Smith] home.”9 Joseph’s mother recalled that Lucy Harris insisted, “I am coming to see him too and I will be there Tuesday afternoon and stop overnight accordingly.”10

Lucy Harris lived up to her promise and traveled to the Smiths’ Manchester home with her daughter to speak with Joseph, hoping to see the plates before she or her husband offered any support for the translation project. Lucy Smith remembered that as soon as Lucy Harris arrived and sat down with Joseph, “she began to importune my son as to the truth of what he said.” She questioned whether Joseph had the plates, and she demanded to see them, believing that she could bargain with Joseph by offering him money to publish the translation of the plates. Joseph explained that the angel who had entrusted the plates into his care forbade him to exhibit the plates to anyone “except those whom the Lord will appoint to testify of them.” After discussing the plates with Joseph again that evening, Lucy Harris made one final plea before she retired to bed, stating, “Now Joseph, . . . I will tell [you] what I will do. If I can get a witness that you do speak the truth I will believe it and I want to do something about the translation and I mean to help you any way.”11

Lucy Mack Smith remembered Lucy Harris having a “remarkable dream” that evening. When she awoke the next morning, she declared that a “personage had appeared to her the night before and said to her that in as much as she had disputed the servant of the Lord and said that his word was not to be believed and asked him many improper questions that she had done that which was not right in the sight of God.” However, after the chastisement from the personage, she was shown the plates in her dream and in the morning she was able to describe the record in detail to her daughter and the Smith family. After discussing the dream and pondering its meaning, Joseph handed Lucy Harris and her daughter the wooden box containing the plates.12 The physicality of the item and sheer weight of the plates served as the evidence that Lucy Harris needed to begin believing that the plates were real. The sound of the plates inside the box may have been partially convincing to the Harrises if the plates shifted inside the box while they held them. Martin Harris remembered that his “daughter said, they were about as much as she could lift. . . . [His] wife said they were very heavy.”13 Even though she knew that Joseph possessed what seemed to be a set of plates, Lucy Harris’s experiences slowly faded from her mind, and she eventually discounted her evening at the Smiths’ as evidence that the plates existed.

His wife’s experience sparked Martin’s interest again. Possibly within days of Lucy Smith’s visit to his home, he traveled to the Smith home to speak with Joseph Smith and to inquire about seeing the gold plates. Harris was surprised to find that Joseph had already planned to include him in the forthcoming effort to translate the plates.14 As Harris later explained, Joseph had seen him in his seer stone after an angel had told Joseph that he would identify “the man that would assist him.” Martin, like his daughter and wife, lifted the box with the plates inside. As some object shifted back and forth in the box, Martin concluded that the object was a set of plates and that their weight indicated that they could have been made of gold. Like a child investigating a wrapped gift, Harris surmised the contents. He knew that Joseph “had not credit enough to buy so much lead,” let alone gold or some other expensive metal. Harris realized that Joseph Smith neither had the means to fabricate nor purchase metal plates. In fact, so destitute were the Smiths, the family had struggled to supply Joseph even with a wooden box. Harris calculated that the plates must have weighed around sixty pounds, which made him believe that, given the size of the box, the plates must have been “lead or gold.”15

Harris approached the situation very skeptically that day. He prepared a plan to interrogate each member of the Smith family separately to uncover any inconsistencies in the stories they told. When he arrived, Joseph was apparently working for Peter Ingersoll as a laborer, which provided Harris a perfect opportunity to talk with the rest of the family without Joseph’s influence. Harris remembered interrogating Emma and other members of the Smith family to try to catch them in a lie. Once Joseph returned, Martin Harris carefully listened as Joseph told the story of the angel and the retrieval of the plates. Joseph also told Martin that God had chosen him to assist in the translation. Knowing that Joseph’s version of the story was in line with the versions his family members had recounted, Martin declared, “If it is the Lord’s, you can have all the money necessary to bring it before the world.”16

One of the more interesting points about these few months between September and November 1827 is how Lucy Mack Smith and Martin Harris remembered these events later. In each of their accounts, they focused on the initial skepticism of Lucy and Martin Harris but quickly turned to the Harrises’ reaction to both spiritual and physical evidence of the plates. Each of them apparently had a vision, and both of them interrogated the Smith family, felt the weight of the plates, and likely heard them move about in the box. Lucy Mack Smith and Martin Harris remembered these early events as proof for why they believed and why others should believe.

Moving to Harmony

While Martin and Lucy Harris were now convinced, not all Palmyra residents reacted so positively. Joseph had worked with many of the laborers in the village digging wells, searching for buried items, and hoping that they would find something in their work that would free them from their daily labors. Moroni had warned Joseph about those who would use the plates to obtain riches and forbade him from showing the plates to any of them. This exclusion provoked those who wanted to profit from the plates. Many were apparently planning to force Joseph to show them the plates, but Harris heard the rumors and warned Joseph before it was too late.17 As Harris later remembered, “The excitement in the village upon the subject had become such that some had threatened to mob Joseph, and also to tar and feather him.” They further declared, “He should never leave until he had shown [them] the plates.”18

Joseph and Emma Smith’s home in Harmony, Pennsylvania. Photo by George Edward Anderson. Courtesy of Church History Library.

With the growing threats from angry residents, Joseph needed a way to leave Palmyra quickly to live with Emma’s family in Harmony, Pennsylvania. Though he did not own a farm, he likely had other things tying him to Palmyra—namely, numerous accounts on credit to pay for his living expenses. Most shopkeepers worked on credit instead of exchanging bills or notes, binding individuals to their local market. As they acquired goods from the shops on credit, they later replenished the shop inventory with their own stock of goods produced on their farms or from their trade. If Joseph had attempted to leave before satisfying his debts, a disgruntled creditor could have demanded a warrant for his arrest. In a local tavern, Martin presented Joseph with fifty dollars so Joseph could settle his debts and do the work of the Lord. Harris declared his intention publicly to “give the money to the Lord and called upon all present to witness to the fact that he gave it freely and did not demand any compensation or return.”19

His debts settled, Joseph “was ready to set out for Penn[sylvania].” A large group of antagonists, however, met to persuade a local physician, Dr. Alexander McIntyre, to help them “follow Joe Smith and take his Gold Bible away from him.” Having served as the Smiths’ physician for some years, McIntyre refused and told the group that “they must be a pack of devilish fools.”20 Having been rejected by a prominent citizen of Palmyra, the disappointed mob subsequently disbanded.

Still fearing for the safety of the plates, Joseph went to great lengths to hide them. Emma’s brother Alva had come up from Harmony with his wagon to help Joseph and Emma move, and Joseph carefully concealed the plates for the several days’ journey to Harmony in the wagon. Evidence suggests that the plates had been transferred between at least three boxes before the group left for Harmony. Martin helped Joseph put the box containing the plates into a barrel, which was filled with beans and then was nailed shut.21 The efforts they made to hide the plates were soon rewarded. Not long after they left Palmyra, a man claiming to have a search warrant stopped them to search their wagon for the plates. After a thorough search, in which he may have even sifted through the barrel of beans, he did not find the plates and likely returned to the village to report that Smith did not have the plates. Soon after the first search was finished, a second man approached the wagon and conducted a search for the plates, again to no avail.22 Orson Pratt later highlighted this story in a popular Latter-day Saint pamphlet, An Interesting Account of Several Remarkable Visions (1840), which describes many of the miracles and angelic visitations from the founding period of the Church. Pratt included this story as just one example of how the Lord protected the plates.

On their way to Harmony, the Smiths stopped in Harpursville, near Colesville, New York, to see Emma’s sister Elizabeth Hale Wasson. According to one late account, while they were there Elizabeth’s husband helped Joseph by giving him a trunk where he could store the plates.23 While Joseph had been forced with previous boxes to nail the box shut to prevent people from looking at them, with this new box (possibly the fourth box in which Joseph had stored the plates), the plates were much more accessible, because it had a lock on the lid. It was also the last box used to store and protect the plates that is mentioned in the historical record. Once Joseph settled in his home in Harmony in late November or early December 1827, he only occasionally went to any length to hide the plates. Emma later recalled, “They lay under our bed for a few months but I never felt the liberty to look at them.”24 For her part, Emma explained, “The plates often lay on the table without any attempt at concealment, wrapped in a small linen table cloth.”25 Emma’s son Joseph Smith III also remembered, “My mother told me that she saw the plates in the sack, for they lay on a small table in their living room in their cabin on her father’s farm, and she would lift and move them when she swept and dusted the room and furniture. She even thumbed the leaves as one does the leaves of a book, and they rustled with a metallic sound.”26

When they arrived in Harmony, Joseph and Emma may have lived in her father’s house for a short time, but they soon moved onto the Hales’ adjoining property in 1828, which Emma’s brother Jesse had owned previously after receiving the property from their father.27 Emma was in her first trimester of pregnancy, and the opportunity to move back to Harmony offered them safety from the growing opposition in Palmyra. The property also gave Joseph the opportunity to start a new life as a farmer.28 The fourteen-acre farm included a frame home, a barn, and other improvements, which Joseph formally purchased from Isaac Hale on 6 April 1829.29

His arrival in Harmony did not come without problems, most of which were related to Emma’s family. Joseph had first met Emma while he boarded at the Hales’ house in the fall of 1825. Joseph and Emma went against Isaac Hale’s wishes when they eloped in January 1827. By August 1827, Joseph had apparently tried to make amends with his new father-in-law, who subsequently offered to help Joseph and Emma get started in their new life. Joseph had opted instead at that time to move to his parents’ house in Palmyra, awaiting the time when Moroni would finally allow him to take possession of the gold plates. Belatedly taking Isaac Hale up on his generous offer, Joseph began to live the life of a poor farmer. In fact, Isaac Hale insisted that the price of his arrangement was that Joseph would stop accepting work as a laborer digging for buried silver or gold.30 Hale was quickly disappointed to find that Joseph claimed he had brought with him from Palmyra a set of gold plates that had been buried in a hill. Hale received these claims with doubt and derision. To make matters worse, Joseph was still under the angelic injunction to show the plates to no one and could not therefore easily allay his father-in-law’s concerns. Attempting to convince Hale that the plates existed without showing him the actual plates, Joseph picked up the trunk in which he had deposited the plates and handed it to Hale. Hale remembered vividly the exercise: “I was allowed to feel the weight of the box and they gave me to understand, that the book of plates was then in the box—into which, however, I was not allowed to look.” As he had done months earlier with the Harrises, Joseph used this approach to avoid the consequences of showing the plates to others while also offering at least some physical evidence that the plates existed. The experience, however, did not make a believer of Isaac Hale the way it had Martin Harris. Given Hale’s willingness to forgive Joseph and Emma and give them favorable terms on his land, he expected Joseph to show him the plates out of respect. Infuriated with what he perceived as Joseph’s recalcitrance, Hale demanded that nothing be stored in his house if he could not see it.31

Hale’s experience illustrates the reluctance certain individuals had when they heard that Joseph Smith had a set of ancient gold plates. Joseph’s insistence on keeping the plates out of sight expressed his devotion to the translation and his promise to Moroni, but it also increased curiosity and doubt in the minds of skeptics. The weight of the plates and the fact that he likely heard the sound of metal moving in the trunk was evidence of something to Isaac Hale, but he wanted to hold the plates and inspect their inscriptions before he believed that the plates were not just a cheaply forged fabrication locked inside a trunk. Perhaps it was in part to try to satisfy Hale’s doubts that Joseph soon produced paper copies of the characters on the plates.

Characters on the Plates

Once Joseph and Emma were living in Jesse Hale’s former home, their separate living quarters on the property gave them enough autonomy to begin working on the plates. Still driven by Moroni’s commandment to translate the plates, Joseph began by doing what Isaac Hale had wanted to do—inspecting them and examining the characters inscribed on their pages. Joseph only had a rudimentary knowledge of written English and had never studied even Greek and Latin like university graduates would have done, let alone lesser-known ancient languages. Joseph had absolutely no ability to decipher any language other than English. He had told Joseph Knight Sr. soon after he had retrieved the plates from the hill that he “want[ed] them translated.” Once in Harmony, as Knight wrote, Joseph “began to be anxious to git them translated” and “with hist wife Drew of[f] the Caricters exactly like the ancient and [later] sent Martin Harris to see if he Could git them Translated.”32

Latter-day Saint historians have been well aware of these accounts, yet Joseph’s early attempts to find a translator of the transcribed characters has been almost completely lost to Latter-day Saint history.33 Without showing them the plates, Joseph had others help him duplicate some of the characters. Emma Smith, for instance, aided Joseph to make copies of the characters, but she never saw the plates herself. It is possible that Joseph was making copies of the characters by placing a paper over the plates and rubbing a piece of charcoal over the inscribed characters. Joseph may have created rubbings of dozens of the plates, then handed them over to Emma to trace or copy the characters onto another piece of paper. Emma would have done her best to replicate the rubbing (if that was how Joseph actually made the copies), but she did not copy characters directly from the plates.

Aside from his wife, Joseph apparently had others help him make copies of the characters from the pages. Late interviews of Harmony residents indicate that Reuben Hale, Emma’s brother, may have also helped create copies of the characters. One local historian reported that Reuben “assisted Joe Smith to fix up some characters such as Smith pretended were engraven on his book of plates.”34 Though the historian’s report was skeptical toward their authenticity, it pointed towards an additional person who may have helped Joseph make copies.35 If Joseph produced only one sheet of copied characters, as the history has traditionally been told, why would Joseph have employed two scribes in this period? Furthermore, if there was only one sample, and Joseph had already made the copy himself directly from the plates, why have any scribe at all? Yet there are records indicating not only that Joseph Smith used Emma and Reuben Hale as scribes, but also that he had Martin Harris create other copies of some characters, presumably after Emma and Reuben had assisted.36

Smith had the plates in his possession for over four months before Harris took copies of the characters to New York City in February 1828, allowing for the possibility that Joseph had, during that time, studied the characters and made numerous copies.37 The copies of these characters allowed Joseph Smith and his followers to provide physical evidence to doubters that the plates did exist.38 Safely living in Harmony, Pennsylvania, over one hundred miles from those who tried to take the plates from him in Palmyra, Joseph began a new era of working with the gold plates.

Notes

^1. See Richard L. Anderson, “Martin Harris, the Honorable New York Farmer,” Improvement Era, February 1969, 18–21.

^2. Tiffany, “Mormonism,” August 1859, 167–68. Harris stated, “The first time I heard of the matter, my brother Presarved Harris, who had been in the village of Palmyra, asked me if I had heard about Joseph Smith Jr., having a golden bible.” See Bushman, Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling, 48–52; Mark Ashurst-McGee, “Moroni as Angel and as Treasure Guardian,” FARMS Review 18, no. 1 (2006): 34–100; D. Michael Quinn, Early Mormonism and the Magic World View, rev. ed. (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1998), 30–65; Ronald W. Walker, “Joseph Smith: The Palmyra Seer,” BYU Studies 24, no. 4 (Fall 1984): 461–72; and Alan Taylor, “The Early Republic’s Supernatural Economy: Treasure Seeking in the American Northeast, 1780–1830,” American Quarterly 38 (Spring 1986): 6–33.

^3. Tiffany, “Mormonism,” August 1859, 163. Harris explained that he saw Joseph use the seer stone in the years before 1827.

^4. Tiffany, “Mormonism,” August 1859, 167. Joseph had by some accounts retrieved one of his seer stones buried underground, stored in a brass kettle. Brigham Young explained that Joseph’s seer stone was “obtained . . . in an Iron kettle 15 feet under ground. He saw it while looking in another seers stone which a person had. He went right to the spot & dug & found it.” Scott G. Kenney, ed., Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 1833–1898 Typescript (Midvale, UT: Signature Books, 1983–1991), 5:382–83; see also Howe, Mormonism Unvailed, 257–58; Wayne Sentinel, 27 December 1825, 2.

^5. Tiffany, “Mormonism,” August 1859, 18.

^6. Lucy Mack Smith, History, 1845, book 6. Compare Tiffany, “Mormonism,” August 1859, 168.

^7. Lucy Mack Smith, History, 1845, book 6, [4–7].

^8. Tiffany, “Mormonism,” August 1859, 168.

^9. Tiffany, “Mormonism,” August 1859, 168.

^10. Lucy Mack Smith, History, 1845, book 6, [4].

^11. Lucy Mack Smith, History, 1845, book 6, [5].

^12. Lucy Mack Smith, History, 1845, book 6, [5–7].

^13. Tiffany, “Mormonism,” August 1859, 168.

^14. Tiffany, “Mormonism,” August 1859, 168. Joseph apparently stated, “Well, I say [see] you standing before me as plainly as I do now” in the seer stone.

^15. Tiffany, “Mormonism,” August 1859, 168. Harris stated, “Wile at Mr. Smith’s I hefted the plates, and I knew from the heft that they were lead or gold, and I knew that Joseph had not credit enough to buy so much lead.”

^16. Tiffany, “Mormonism,” August 1859, 168–70.

^17. Tiffany, “Mormonism,” August 1859, 170.

^18. Tiffany, “Mormonism,” August 1859, 170.

^19. Lucy Mack Smith, History, 1845, book 6–7.

^20. Lucy Mack Smith, History, 1845, book 6–8.

^21. Lucy Smith wrote that the plates were “severely nailed up in a box and the box put into a strong cask made for the purpose the cask was then filled with beans and headed up as soon as it was ascertained.” Lucy Mack Smith, History, 1845, book 6–7. See also Howe, Mormonism Unvailed, 13–15, 18; Rhamanthus M. Stocker, Centennial History of Susquehanna County, Pennsylvania (Philadelphia: R. T. Peck, 1887), 554–55; Orson Pratt, A[n] Interesting Account of Several Remarkable Visions, 1840, in JSP, H2:13–14.

^22. Pratt, A[n] Interesting Account, 401.

^23. “The early Mormons,” Binghamton Republican, 29 July 1880.

^24. Emma Smith Bidamon Interview by Nels Madson and Parley P. Pratt, Church History Library, SLC, 1877.

^25. Joseph Smith III, “Last Testimony of Sister Emma,” Saints’ Herald, 1 October 1879, 289–90.

^26. Joseph Smith III to Mrs. E. Horton, 7 March 1900, CCLA, in Dan Vogel, Early Mormon Documents, 1:546–47.

^27. See Harmony Assessment Records, 1828–1831, court records, Susquehanna County Courthouse, Montrose, Pennsylvania, 10, 11, 13, and 14.

^28. Joseph Smith, History, 1834–1836, in JSP, H1:9; Joseph Smith III, “Last Testimony of Sister Emma,” Saints’ Herald, 1 October 1879, 289; “Mormonism,” Susquehanna Register (Montrose, PA), 1 May 1834, [1].

^29. Agreement with Isaac Hale, 6 April 1829, in JSP, D1:29; For the Harmony tax records, see Vogel, Early Mormon Documents, 4:421–31. The frame home was twenty-five by twenty feet and included a large cellar with windows, fenced in by a well-built stone wall. It also included a well in the front yard and a spring flowing from the hill behind the house. It is also likely that the property included plowed fields and a few orchards. The north end of the property had maple trees and sugar bushes for maple sugar. It was at the northern end of his property that Joseph likely kept the gold plates hidden away from the “abodes of men” once he removed them from the house.

^30. When Joseph faced charges of being a disorderly character in July 1830, Joseph’s use of a seer stone was discussed, with the court concluding that he had not searched for buried treasure for at the very least two years. Josiah Stowell believed that Joseph had not been actively involved in money digging since 1826. “Mormonism,” New England Christian Herald, 7 November 1832, 22–23.

^31. Howe, Mormonism Unvailed, 257–58.

^33. Michael Hubbard MacKay, Gerrit J. Dirkmaat, and Robin Scott Jensen, “The ‘Caractors’ Document: New Light on an Early Transcription of the Book of Mormon Characters,” Mormon Historical Studies 14, no. 1 (Spring 2014): 131–52; Michael Hubbard MacKay, “Git Them Translated,” in Approaching Antiquity: Joseph Smith’s Study of the Ancient World (forthcoming, paper presented at the 2013 Church History Symposium, Provo, UT, March 7, 2013).

^34. Blackman apparently interviewed a local resident, who stated that Reuben “assisted Joe Smith to fix up some characters such as Smith pretended were engraven on his book of plates.” Blackman, History of Susquehanna County, Pennsylvania, 104; Knight Sr., History, 3.

^35. Clearly, possibilities abound, because little is known about the origin of these documents. Joseph may have made rubbings and had scribes create handwritten copies, or he may have copied them and used scribal assistance to make better copies or multiple copies, but ultimately nothing is known about the creation of the documents.

^36. Joseph Smith, History, circa Summer 1832, in JSP, H1:15.

^37. See MacKay, Dirkmaat, and Jensen, “The ‘Caractors’ Document,” 131–40.

^38. Martin showed the characters he had copied from the plates to individuals throughout his lifetime. See John A. Clark, Gleanings by the Way (Philadelphia: W. J. & J. K. Simon, 1842), 217, 222–31. G. W. Stoddard, who was a farmer in Wayne County, New York, claimed Harris was a Universalist and a Methodist. See Howe, Mormonism Unvailed, 260–61; Orsamus Turner, History of the Pioneer Settlement of Phelp’s and Gorham’s Purchase and Morris’ Reserve (Rochester, NY: Erastus Darrow, 1851), 215; and Henry G. Tinsley, “Origin of Mormonism,” San Francisco Chronicle, 14 May 1893, 12. For accounts of others who claimed to see the characters from Harris, see Clark, “Gleanings By the Way”; Episcopal Recorder, 5 September 1840, 94; and Orsamus Turner’s recollection in Turner, History of the Pioneer Settlement, 215.