2 Break the Bonds of Boredom

Let others bemoan the maliciousness of their age. What irks me is its pettiness, for ours is an age without passion …

My life comes out all one colour.

Kierkegaard

If contemporary science were more sophisticated and subtle, then I’m absolutely certain that it would rank boredom as one of the central killers in the modern world. The Belgian writer Raoul Vaneigem, one of those anarchic work-avoiders called the Situationists and a friend of Guy Debord, wrote in The Revolution of Everyday Life (1967), ‘People are dying of boredom,’ and I believe this quite literally to be true. Greyness and boredom are not only enemies of merry living, they are murderers. It would not surprise me one jot if boredom were one day revealed to be carcinogenic.

Boredom was invented in 1760. That is the year, according to academic Lars Svendsen in his excellent study A Philosophy of Boredom (2005), that the word was first used in English. The other great invention of the time was the Spinning Jenny, which heralded the start of the Industrial Revolution. In other words, boredom arrives with the division of labour and the transformation of enjoyable autonomous work into tedious slave-work.

And we are very bored. Go into chat rooms and forums on the Internet between three and five in the afternoon and you will find hundreds of posts from office workers reading, ‘Bored bored bored!’ These pleas for help, these desperate entreaties from trapped spirits, are like messages in a bottle, sent out into the ether, into the the oceans of cyberspace, in the hope that someone out there is listening and that someone out there may be able to do something to help. The odds, of course, are low.

I recently helped compile a book called Crap Jobs. We had asked readers of the Idler to send in their stories of workplace hell, and one thing that struck me was how many people cited boredom as one of the worst aspects of working. They found the boredom almost literally unbearable and would resort to all kinds of tactics to overcome it: office sabotage, crude banter with co-workers, irresponsible acts. One of the problems is that many modern jobs require just enough concentration to prevent you from going off into a dream but not enough really to occupy your mind. Jobs which are totally mechanical can be preferable, for example, to call-centre jobs. Call centres bore their customers to tears, and they bore their employees to death. Low pay is combined with the psychic torture of not knowing what fresh hell the next call is going to present you with.

Our other recent publication was called Crap Towns, and again what was striking was that the uniformity of the modern town was often cited as one of the reasons for it being crap. Something awful has happened, which is that giant retail chains have turned our towns – once so vibrant, teeming and various – into identikit retail centres peopled by shopping zombies. A town today is little more than a circle of flats gathered around a vast, airless shopping mall. Our hearts sink when we walk down the high street. We are assaulted with brand names, colourless institutions that have replaced all the fun and difference of the old stores, the grocers, haberdashers, fishmongers, bakers, florists, cobblers and apothecaries. The drive for growth and economies of scale has driven the independent spirit away. Almost. Occasionally an old Victorian shopfront survives, and its beauty, elegance and sense of fun shines out like a rainbow. There are other rays of hope: yesterday I saw a sign in the town nearest to me which cheered me. It was in the window of a TV repair shop, another dying breed of service. The sign said: ‘Old-fashioned service by the proprietor.’

To E. F. Schumacher’s notion that ‘Small is beautiful,’ we could certainly add ‘Big is boring,’ as it is the sheer scale of modern institutions which makes them so impersonal, alienating and exhausting to the spirit. McDonald’s is boring and my local Indian is not boring. Raoul Vaneigem wrote, also in The Revolution of Everyday Life, that quantity has conquered quality. We have become so obsessed by numbers and by bottom lines that beauty and truth have been knocked aside. Boredom is the very opposite of beauty and truth. Life has been sacrificed to profit, and the result is boredom on a mass scale.

One of the principal causes of boredom, it seems to me, is the removal of everyday creativity from the people. This was certainly the problem as William Morris saw it. In News From Nowhere, Morris paints a post-revolutionary society, in 2005, in which everyone is involved in some kind of freely chosen creative activity. There is no money, and Piccadilly Circus is covered with fields. This is how he saw the fourteenth century, and whether or not he romanticized the Middle Ages is not the point: it exists as a worthy ideal. The Puritan Revolution began to introduce boredom to the masses. Even religion and the path to salvation became boring. In the Middle Ages, religion had been full of blood and gore and death. Churches were centres of economic activity and partying as well as of worship. The Church was a patron of the arts and commissioned local craftsmen to make adornments for its properties. The sermons were attended largely for their entertainment value; they provided real theatre. In medieval Florence, people would queue all night to see a great preacher and would then stream out of the church after the service, weeping copiously. All this drama and theatre was removed by the Puritans, who labelled the ways of the old church ‘superstition’ and ‘idolatry’. In other words, all the pagan fun of the Catholic Church, which it had wisely kept, was taken away.

Politicians can also take a fair share of the blame for the perceived monotony of our lives. You don’t hear governments coming out with lines like ‘Tough on boredom. Tough on the causes of boredom.’ The most stupefyingly boring of all governments – and all governments are boring by their very nature – was the Nazis. Lines and rows and columns, the absence of individuality, the imposition of a bureaucratic order on things, the systematic removal of everything interesting – particularly Jews, but also gypsies, vagrants, the workshy and political dissidents. The Nazis loved sending memos, filling in forms, filing, cataloguing, keeping everything neat and tidy. What the Nazis attempted was a great big tidy-up, like the Puritans before them, and that is why excessive tidiness must be resisted.

The main reason that so many people are so desperately bored is that boring people are in charge. The money-makers, the profit-driven capitalists, high priests of utter dullness, run the business side of things. And the bureaucrats, the form-fillers and health-and-safety enthusiasts, are running the government. They actually like boredom. Being alive would scare them. But it hasn’t always been this way, and it need not always be this way. Once upon a time, not so very long ago, the boring people were sidelined as ungodly. In medieval times, particularly the earlier periods, those with bourgeois, money-making values were looked down upon by the warriors, clerics and peasants. ‘There is something disgraceful about trade, something sordid and shameful,’ wrote opinion-former St Thomas Aquinas. Happiness, he said, was to be found in reflection, not distraction:

So, if the ultimate felicity of man does not consist in external things which are called the goods of fortune, nor in the goods of the body, nor in the goods of the soul according to its sensitive part, nor as regards the intellective part according to the activity of the moral virtues, nor according to the intellectual virtues that are concerned with action, that is, art and prudence – we are left with the conclusion that the ultimate felicity of man lies in the contemplation of truth.

Boredom is a form of social control. Contemporaneous with the emergence of boredom in the late nineteenth century, we find an attack on the notion of the plebs organizing their own fun. As we all know, art and entertainment in previous ages was a bottom-up affair. All dramatics were amateur, mystery plays were performed by the craftsmen’s guilds; medieval artists were also craftsmen. But radical historian E. P. Thompson shows us how suspicious the authorities became of such democratic art production as the Industrial Age dawned and control of both work and leisure was taken from the people. He cites, in The Romantics, the well-meaning reply of a local posh liberal to an application by a factory man to put on a play in 1798: ‘The play,’ she worries, ‘might have a tendency to do you harm, and to prepare you for following scenes of riot and disorder at the alehouse.’ To Thompson, this anecdote proves the increasing ‘fear of an authentic popular culture beyond the contrivance and control of their betters’. Thompson also blames a centralized education system and cites a letter written in 1911, surprisingly, by a former chief inspector of schools, which criticizes the education system for being boring: ‘The aim of his teacher is to leave nothing to [the pupil’s] nature, nothing to his spontaneous life, nothing to his free activity; to repress all his natural impulses; to drill his energies into complete quiescence; to keep his whole being in a state of sustained and painful tension.’

Boredom is painful. For Vaneigem, the pressure to become the same as each other exhausts our spirit: ‘If hierarchical organization seizes control of nature, while itself undergoing transformation in the course of this struggle, the portion of liberty and creativity falling to the individual is drained away by the requirements of adaptation to social norms of various kinds.’

Lest we become too depressed, let us remember that the creative spirit lives on. On the Scottish Isle of Eigg near Skye, the whole island comes together for a drinking and music session every Saturday night. No one is paid; no one is hired. The music is performed for its own sake, not for profit. To fight boredom, we need to take control of our work and our leisure alike. The artist Jeremy Deller has spent many years travelling around the British Isles photographing examples of what he calls Folk Art. For Deller, this means acts of creativity which have been done more or less for their own sake created by ordinary people who would never consider themselves to be artists. This is art outside the art world, outside Cork Street galleries, museums, dealers and the Arts Council: outside, in other words, the worlds of money and bureaucracy. Examples include a giant owl made by a group of farmers, customized cars, doodles in the dust on the back of vans, a painting of Keith Richards on the back of a truck, a giant motorized elephant, gurning competitions. It’s a wonderful project, because what it proves is that the free spirit is very much alive. It means, actually, that against all the odds, boredom has not completely destroyed us.

What can we do to fight boredom? Well, the very same system that has created it also promises to relieve us of it. We are bored by work, and then advertising promises to take our boredom away, once we have handed over our cash. This is called leisure, and the word is derived from the Latin ‘licere’, meaning ‘to be permitted’. Leisure, then, is what we are allowed to do in our ‘spare time’. And it costs. In the UK, vast shops called Virgin Megastores sell piles and piles of prerecorded music and films. In their advertising, they claim to be mounting an attack on boredom. But we shouldn’t allow them to relieve our boredom for us. We have delegated the relief of boredom; we have shirked our responsibility for dealing with it. In other words, we hand over our creativity to the professional musician or film-maker. We pay someone else to alleviate our boredom. We bore ourselves in order to earn the money that we will later spend in trying to de-bore ourselves. That absurd modern trend called Extreme Sports springs to mind. In order to feel alive, because most of the year we feel dead, we hurl ourselves from a bridge every few months. Falling off a bridge, or a few seconds of thrills, is thus supposed to compensate for a whole year of boredom. And the freedom to hurl ourselves from a bridge while tied to an elastic band is held up as one of the great triumphs of modern capitalism.

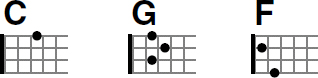

This whole universe of boredom is precisely what was being attacked by the Sex Pistols. I agree absolutely with Johnny Rotten – I don’t want a holiday in the sun. I refuse your paltry offer of two weeks on a beach (boring leisure) as a break from fifty weeks in the office (boring work). In Lipstick Traces, rock ’n’ roll critic Greil Marcus brilliantly relates the Dada movement to the Situationist movement, and both to punk. What they have in common is the rage against boredom, the desire, simply, to live. What all three movements share is the passionate belief that anyone can do it. We can all be creative and we can all be free. The first number of Internationale Situationiste announced in June 1958 that the world was about to change ‘because we don’t want to be bored … raging and ill-informed youth, well-off adolescent rebels lacking a point of view but far from lacking a cause – boredom is what they all have in common. The Situationists will execute the judgement contemporary leisure is pronouncing against itself.’ Punk was about putting creativity back into the hands of the people; anyone can do it, they said and, to prove it, here are the three chords you need to write a song: E, A and B7. Do it yourself.

Well, I can go one better than that. Instead of the guitar, I urge you to take up the ukulele. This four-stringed marvel is very cheap, very portable and very easy to play. It is therefore even more punk than the guitar. Here are the three chords you need to play most songs:

Get a uke and you will never be bored again. You could even make some extra cash by busking. The uke is freedom. Indeed, the Ukulele Orchestra of Great Britain’s first album is called Anarchy in the Ukulele, and aptly titled it is too.

Behind the attack on boredom is a radical desire to take control of our lives back from the giant organizations to whom we have more or less willingly entrusted ourselves. This is an act of gross irresponsibility on our part. But it is not too late. We simply need to discover our own creativity. The simple way to avoid boredom is to make stuff; already, there are the glimmerings of a new movement in this area, to which the success of US magazine Ready Made (www.readymademag.com) bears witness. My heart also soars when I see skateboarders. Having worked in a skateboarding shop for a year, I know what a radically creative and positive pursuit skateboarding is. It is a self-governing movement, a federation, with its own magazines, fanzines, competitions and businesses, all displaying a high level of ingenuity, independence and creativity. One of the latest companies on the scene is the brilliantly named Death Skateboards, who have the equally effective slogan, ‘Death to Boredom’, and three cheers for that.

PLAY THE UKULELE