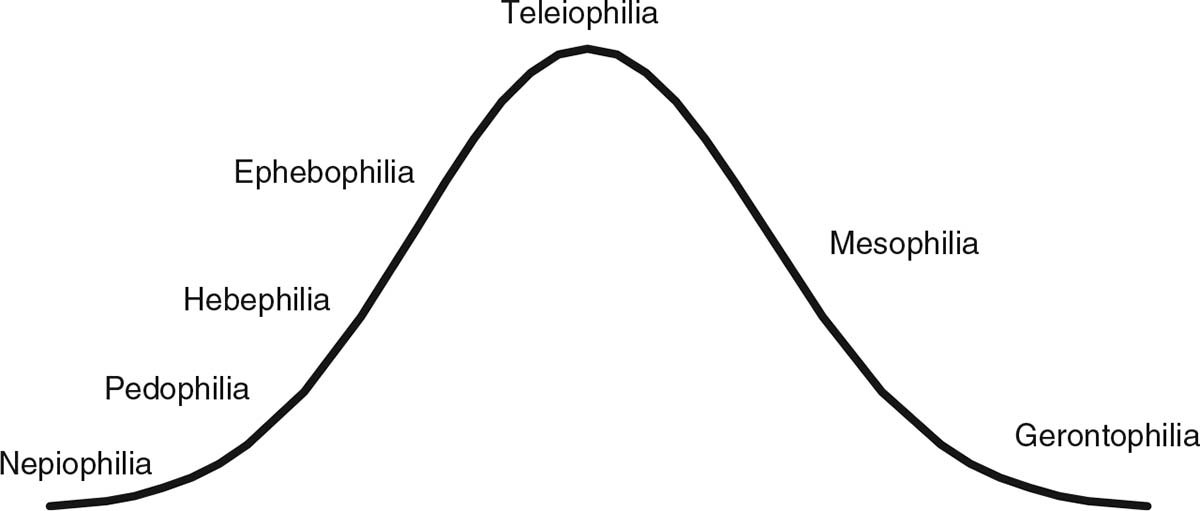

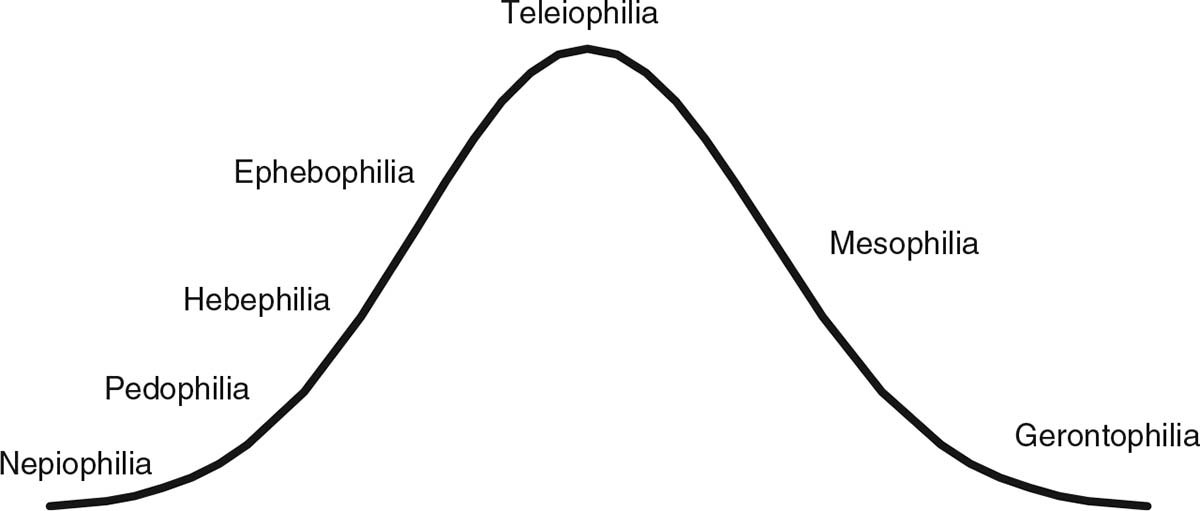

Figure 1.1.

Hypothetical relative frequency distribution of chronophilias among men. The actual frequency of chronophilias is unknown; existing evidence suggests most women are teleiophilic. From “The Puzzle of Male Chronophilias,” by M. C. Seto, 2017, Archives of Sexual Behavior

, 46

, p. 7. Copyright 2017 by Springer. Reprinted with permission.

CRITERIA FOR PEDOPHILIA

The following criteria from the

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

(fifth ed. [

DSM–5

]; American Psychiatric Association, 2013) for ascertaining pedophilia were in effect when I wrote this text in May 2016, unchanged from the previous version of the

DSM

(i.e.,

DSM–IV–TR

; American Psychiatric Association, 2000) except to make the distinction between ascertaining a paraphilia and diagnosing a paraphilic disorder. The latter, diagnosing a paraphilic disorder, involves evidence of clinically significant distress or impairment: (a) over a period of at least 6 months, recurrent, intense sexually arousing fantasies, sexual urges, or behaviors involving sexual activity with a prepubescent child or children (generally age 13 years or younger) and (b) the person has acted on these sexual urges, or the sexual urges or fantasies cause marked distress or interpersonal difficulty (American Psychiatric Association, 2000, 2013).

The World Health Organization’s (2016)

International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems

(10th rev.; ICD–10) has similar criteria: (a) The general criteria for disorders of sexual preference must be met, including recurrent, intense sexual urges and fantasies involving unusual objects or activities, acts on the urges or is markedly distressed by them, and the preference has been present for at least 6 months; (b) a persistent or a predominant preference for sexual activity with a prepubescent child or children; and (c) the person is at least 16 years old and at least 5 years older than the child or children in Criterion b. The World Health Organization is now working on the 11th version of the ICD (ICD–11), with a proposed deadline of 2018 (

http://www.who.int/classifications/icd/revision/en

). At the time of this writing, the draft ICD–11 criteria for pedophilic disorder are

Pedophilic disorder is characterized by a sustained, focused, and intense pattern of sexual arousal—as manifested by persistent sexual thoughts, fantasies, urges, or behaviours—involving pre-pubertal children. In addition, in order for Pedophilic Disorder to be diagnosed, the individual must have acted on these thoughts, fantasies or urges or be markedly distressed by them. (ICD–11, 7D72)

Krueger et al. (2017) described the revision process and explained the rationale for the proposed ICD–11 criteria for paraphilic disorders, including pedophilic disorder (following the distinction made in

DSM–5

). They noted that the criteria were intended to rule out sexual behaviors involving children with similar-aged peers. Krueger et al. also noted that a history of sexual behavior involving children was not sufficient to establish the diagnosis, because of the possibility of nonsexual or other explanations for this behavior; evaluators needed to consider whether sexual behavior with children reflected a sustained, focused and intense pattern of sexual arousal to prepubescent children. The authors urged caution in considering the diagnosis for adolescents who had engaged in sexual behavior with children, unless evidence indicated that this behavior was persistent and reflected a sustained, focused, and intense pattern of sexual arousal to prepubescent children.

Sexual offenses are defined by law and vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. However, most jurisdictions, especially the English-speaking countries where this book is likely to be read, share commonalities. First, sexual contacts or attempted contacts with children under a legally defined age of consent is prohibited. The age of consent is 16 in Canada and in many of the American states. It is lower in some countries (e.g., 14 in Austria, Germany, Italy, and Portugal), but given that the average age of onset of puberty for girls is 12 and boys is 13, it is still the case that sexual contacts with most prepubescent children and many pubescent children are illegal. In the same countries, possession, distribution, and/or production of pornography depicting prepubescent or pubescent children is illegal, either in specific child pornography laws or more general obscenity laws (International Center for Missing and Exploited Children, 2016). Some nations have prohibited online sexual solicitations of minors.

Neither pedophilia nor hebephilia is synonymous with sexual offending against children, although these terms are often used interchangeably. But some persons with pedophilia or hebephilia are not known—despite thorough police investigations and pertinent questions—to have ever committed sexual offenses involving children, and a substantial proportion of identified sex offenders against children are motivated by reasons other than pedophilia or hebephilia. Nonoffending persons with pedophilia are likely to differ from pedophilic offenders in important ways, and pedophilic and nonpedophilic offenders differ in their risk to reoffend and in the interventions that have the best chance of preventing future crimes.

The assumption seems to be that someone who would engage in such sexual acts must be paraphilic, because it is otherwise incomprehensible behavior to most nonoffending, teleiophilic people (i.e., people with a species-typical interest in young, sexually mature adults). Public and media discussion of pedophilia and sexual offending shows a conflation of the two concepts, reflecting this intuition. But it is not correct: Some persons with pedophilia or hebephilia have not committed sexual offenses involving children, and a substantial number of identified sex offenders with child victims would not meet the classification criteria for pedophilia or hebephilia. Also, because of imprecise use of the term

pedophilia

in media and public discourses, offenders against legal minors, including postpubescent youth, are sometimes inaccurately referred to as persons with pedophilia. Similarly, offenders against sexually maturing adolescents under the legal age of consent (16 in Canada and across the United States, so offenses against 14- or 15-year-olds) are mistakenly referred to as persons with hebephilia in the clinical and research literatures.

Hebephilia as a clinical and sexological concept has been around for decades (see Cantor, n.d.). Stephens (2015) conducted the largest set of studies focusing on hebephilic sexual offending, including how well different indicators agree with each other (convergent validity), how distinctive they are from pedophilia indicators (divergent validity), and what hebephilia means for recidivism (predictive validity). She found good evidence for convergent validity, with expected associations between self-reported sexual interest in pubescent children, having victims ages 11 to 14, and sexual arousal to pubescent children in the lab. Evidence for divergent validity was mixed because hebephilia indicators were sometimes more strongly related to pedophilia indicators than to other hebephilia indicators. The evidence for predictive validity was mixed, with pedophilia or hebephilia indicators predicting noncontact but not contact sexual recidivism, despite prior studies showing phallometrically assessed sexual arousal to children is one of the strongest predictors of sexual recidivism among identified sex offenders (Hanson & Bussière, 1998).

Readers may be aware of the vigorous debate about the inclusion of hebephilia in

DSM–5

. Much of this debate did not focus on whether hebephilia represented a distinct chronophilia but instead whether it met the

DSM

definition of mental disorder and whether it would be (mis)used in legal proceedings as an additional justification for civil commitment of sex offenders in the United States (see Stephens & Seto, 2016). Important theoretical and clinical questions included whether hebephilia is a distinct chronophilia from pedophilia; whether hebephilia differs in terms of etiology, course, or prognosis; and whether it is valuable to consider hebephilia separately from pedophilia in terms of diagnosis and treatment. There is a reasonable argument for considering pedophilia and hebephilia together as

pedohebephilia

. Puberty is a liminal event and thus hard to capture in clinical or scientific measurement. For many practical purposes, it might not matter much whether an individual’s attraction is to prepubertal or pubertal children. It certainly would be hard to get it right without precisely knowing the Tanner (1990) stage of children for self-report, child pornography and contact offending history, and precise delineation of sexual stimuli in laboratory-based assessments. In other words, the distinction between pedophilia and hebephilia is real but might not be necessary for many practical purposes.

CHRONOPHILIAS

In Seto (2017b), I discussed pedophilia as one form of chronophilia. The youngest category is

nepiophilia

, referring to an even rarer preference for infants or toddlers (Greenberg, Bradford, & Curry, 1995). After

pedophilia

(prepubescent children) comes

hebephilia

(pubescent children) and

ephebophilia

(sexually maturing but not yet mature adolescents). Nepiophilia is sometimes included with pedophilia. Pedophilia is strongly correlated with hebephilia (Stephens, Seto, Goodwill, & Cantor, 2017a), and indeed hebephilia is associated with higher rates of nonexclusivity, probably because the age/maturity category is narrow, the narrowest of any chronophilia.

Teleiophilia

refers to the species-typical sexual interest in young adults. I coined the term

mesophilia

to refer to a sexual preference for middle-aged persons.

Gerontophilia

refers to a sexual preference for elderly persons.

Why do chronophilias matter? First, I believe any deep understanding of pedophilia is going to be connected to a better understanding of chronophilias. It would be surprising if etiology and development did not have commonalities. Most of the interest has been on pedophilia, for clinical and forensic reasons, but the research for the other chronophilias is open terrain. It might be particularly fruitful to explore those that are not illegal if acted upon, because self-report would not be subject to the same biases. Second, pedophilia and other chronophilias can be understood as variations in sexual orientation regarding age, just as hetero-, bi- or homosexuality are variations in sexual orientation regarding gender (where heterosexuality is species typical). This suggests pedophilia may manifest not only in sexual interest in children but also in sexual identity (how one labels and defines one’s sexuality), romantic attractions, and social behavior. It also suggests, although it is not required, that pedophilia emerges early in adolescence, with the onset of puberty, and is stable over time (see Seto, 2012). Consistent with this conceptualization of pedophilia, Tozdan and Briken (2015) examined 75 individuals reporting a sexual interest in children and found the age of reported onset ranged from 6 to 44, with a mean of 17 and a median of 15. The plurality was interested in both prepubescent and pubescent children, with 27% reporting an interest in prepubescent children; 31%, in pubescent children; and 43%, in both age/maturity groups. Age of onset was correlated with flexibility, such that those respondents who reported an earlier age of onset reported less change over time. In contrast to the large online sample described by Bailey et al. (2016), only 20% of this sample saw themselves as exclusively interested in children.

Describing the development of pedophilia and hebephilia, Bailey et al. (2016) found that the average age of awareness of sexual interest in children under the age of 14 in their online sample was 14.2 years; the average age when respondents suspected this was unusual was 16.1 years; and the average age of understanding that this was an atypical sexual interest was 18.1 years. In other words, it took time for individuals to realize their sexual interests were different from their adolescent peers: Their peers’ interests shifted with age, so that their peers continued to be attracted to similar-aged individuals; in contrast, the respondents continued to be attracted to children under age 14, and at some point, the age discrepancy became obvious.

B4U-ACT, an advocacy and education organization operating out of Maryland, conducted a survey in spring 2011 of 193 respondents (98% male) who reported their average age of awareness of their attraction to children was 14 (B4U-ACT, 2011a). The average age of first attraction to children was 12, which likely reflects peer attraction as the person began to undergo puberty. It would be 2 years later, on average, that the person might realize they continued to be attracted to younger children instead of their peers.

Grundmann, Krupp, Scherner, Amelung, and Beier (2016) reported data on the stability of self-reported sexual arousal and interests, from first attraction to prepubescent or pubescent children for 494 persons with pedophilia or hebephilia. The mean age of the sample was 38, and only 7% had never sexually offended: 31% had committed child pornography offenses, 44% had committed both child pornography and contact sexual offenses, and the rest had committed contact but not child pornography offenses. (These are not unbiased estimates of the association between pedophilia or hebephilia and sexual offending because the sample comprised help-seeking individuals, and one would expect that help-seeking would be related to distress or concern about sexual offending.) One third of the Grundmann et al. sample had been previously detected by authorities.

Examining retrospective data first, Grundmann et al. (2016) found that 58% of those who admitted sexual interest in prepubescent girls reported pubertal onset, compared with 72% for those who were attracted to prepubertal boys and 87% for those who were attracted to adult women as well. These values are not close to 100%, perhaps because our phenomenological understanding of our sexual attractions by puberty is incomplete. In the prospective analysis of 121 individuals who participated in treatment and were reassessed, rank-order correlations were moderate to high for median ratings of arousal to prepubescent girls or boys during masturbation, comparable to the correlations for arousal to women or to men. The sample had change in both directions, that is, some individuals showed increased rather than decreased sexual arousal to prepubescent girls or boys. Grundmann et al. also had data on reassessment without treatment, with similar stability estimates for prepubescent girls and for prepubescent boys; stability was higher for interest in boys.

Grundmann et al. (2016) interpreted their results as consistent with the idea that sexual arousal to prepubescent and pubescent children is stable over time, over a period of years in their retrospective study (from adolescence to adulthood) and over an average of 29 months in their prospective study (within adulthood). The stability coefficients might seem low, but Grundmann et al. made the helpful point that the values found for sexual arousal to prepubescent girls or boys during masturbation are comparable to those found in stability studies of major personality factors, such as extraversion or conscientiousness. It is not controversial to argue that personality represents a set of stable psychological traits that vary across situations but are nonetheless characteristic of persons over situations and over time; the same seems to be true for sexual arousal.

Grundmann et al. (2016) did not take measurement error into account in estimating stability, which could have an important effect on stability estimates (see Mokros & Habermeyer, 2016). The values for attraction to women or men were higher than for children, similar to what is found in the general population for stability of gender orientation, so it is consistent with the idea that gender is fixed before age in terms of sexual preference structure and also with the idea that pedophilia and hebephilia have more room for change (Diamond, Dickenson, & Blair, 2017; Seto, 2017b).

THE IMPORTANCE OF PUBERTY

As already noted, an essential element in understanding pedophilia and hebephilia is pubertal status. Sexual contacts with postpubertal adolescents are legally prohibited in many nations, but these prohibitions are arbitrary in the sense that they differ from country to country, and from state to state in the United States. In contrast to the legally determined age of consent, puberty and the concomitant development of secondary sexual characteristics is objective and biologically relevant. Postpubescent individuals are potentially fertile and thus are potential reproductive partners from a biological perspective, notwithstanding legal and social objections. On the other hand, being sexually attracted to nonfertile prepubescent children (pedophilia) would be biologically maladaptive and likely to meet a Darwinian definition of disorder that requires a malfunction of a mechanism as designed, as well as distress or impairment (Wakefield, 1992).

For pedophilia and hebephilia, pubertal status rather than the specific age is critical because the age at which puberty begins varies because of nutrition, health, exposure to exogenous hormones, and other factors. Indeed, the average age of puberty for both girls and boys has declined over the past century in industrialized nations (Herman-Giddens et al., 1997; Herman-Giddens, Wang, & Koch, 2001). Many young girls show some signs of secondary sexual development by the age of 12 or 13. Adults who seek pornography or sexual contacts with girls age 12 or 13 would violate age of consent laws in most jurisdictions but are probably not exhibiting pedophilia (but possibly are exhibiting hebephilia).

DSM

suggests age 11 or younger, but age is an imperfect proxy. Historical accounts of sexual contacts with girls between the ages of 12 and 13, however, may indeed represent pedophilic sexual behavior.

A reliable system for determination of pubertal stage was described by Tanner (1990; see

Figures 1.2

and

1.3

). Tanner Stage 1 is relevant to pedophilia; Tanner Stages 2 and 3, to hebephilia; Tanner Stage 4, to ephebophilia; and Tanner Stage 5, to teleiophilia. Nepiophilia, mesophilia, and gerontophilia are not explicitly included in the Tanner system. For girls, Tanner stages are based on pubic hair, appearance of the vulva, emergence of breasts, and axillary hair. For boys, Tanner scores are based on the appearance of the penis and scrotum. The Tanner system does not consider other physical features that are also likely to be relevant to pedophilic attraction, particularly body size and shape.