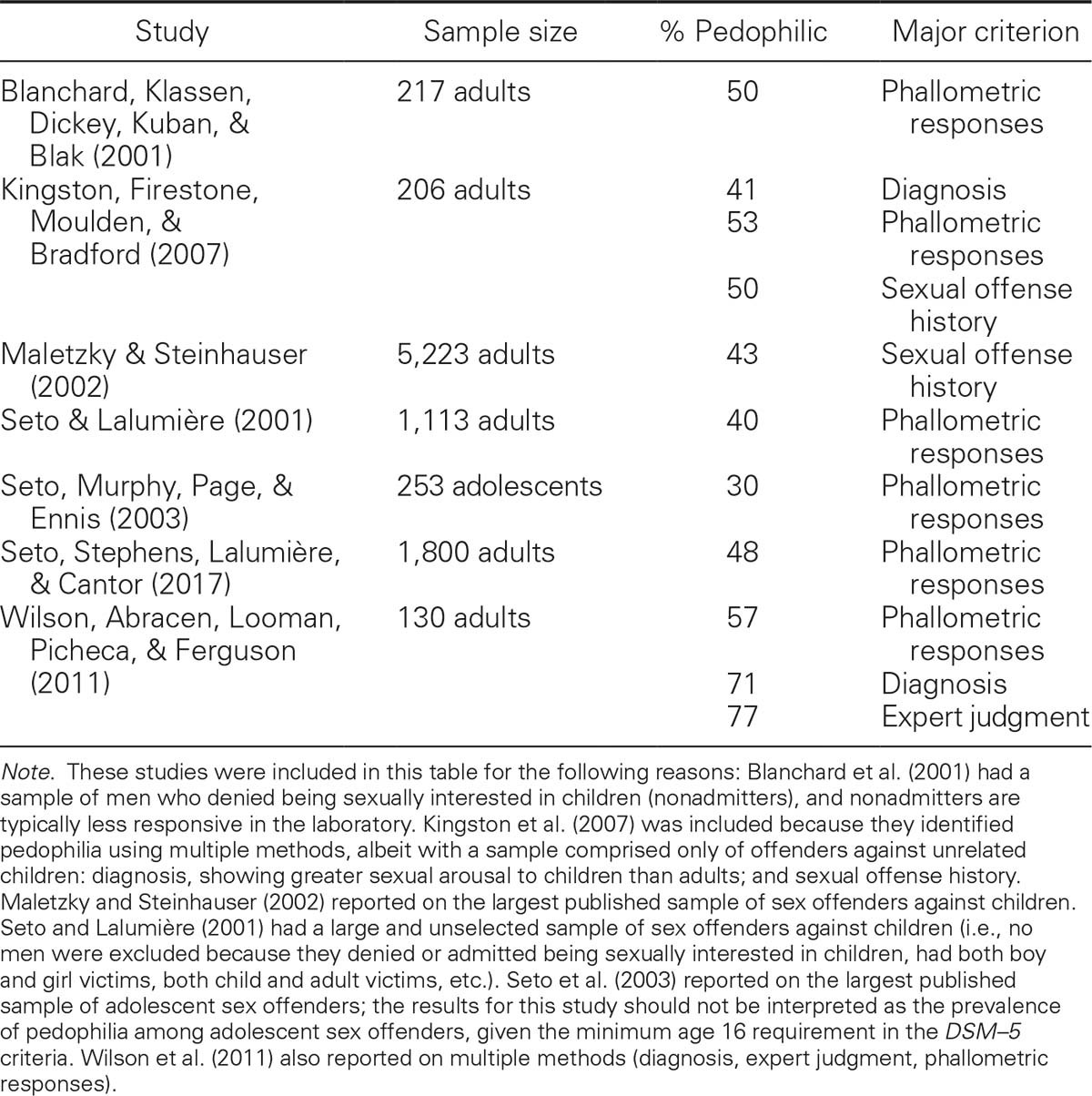

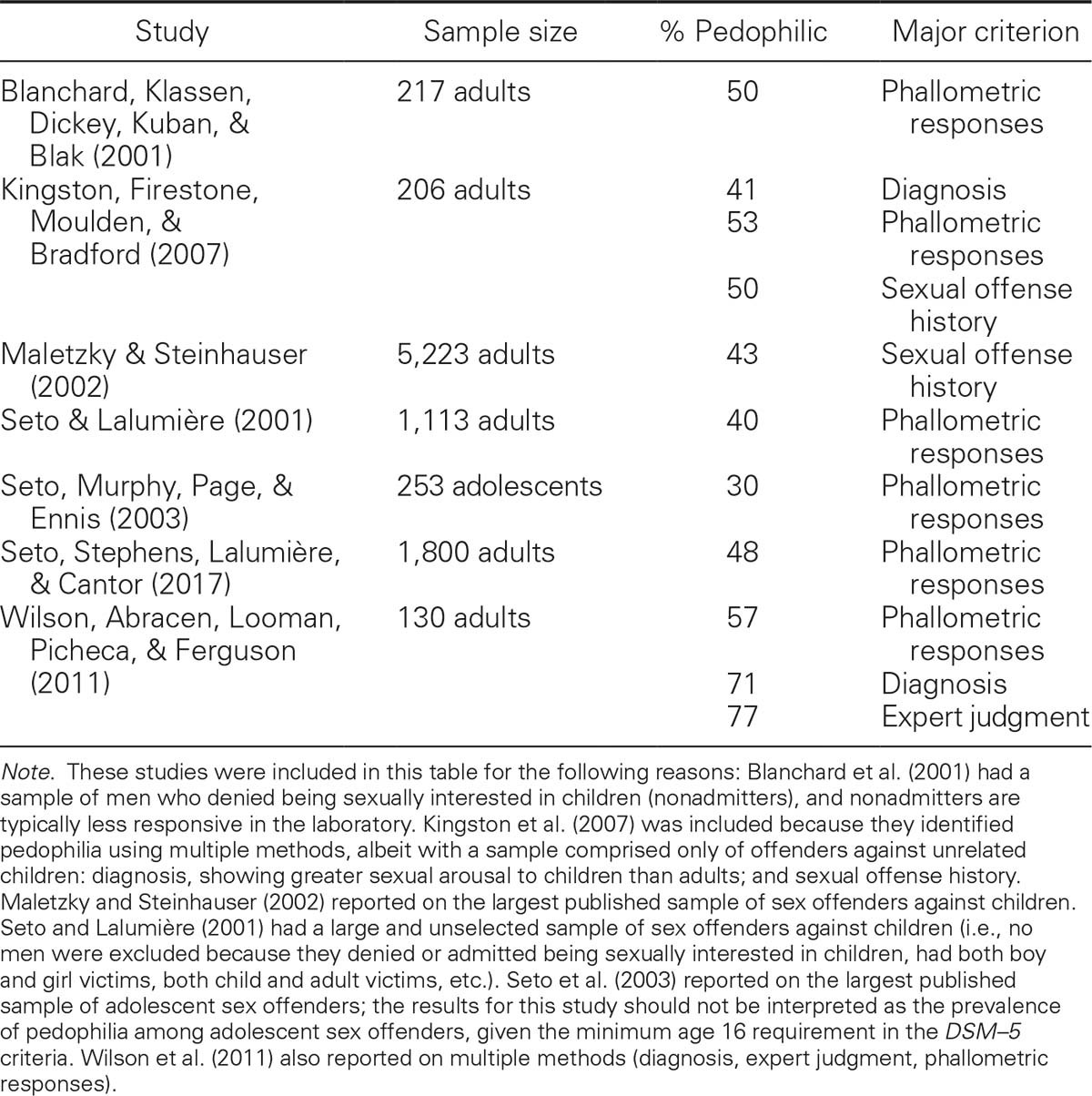

TABLE 1.4

Percentage of Sex Offenders With Child Victims Who Are Likely To Be Pedophilic (Selected Samples)

In the next two sections, I review the historical and cross-cultural evidence about adult–child sex to examine the extent to which this behavior has appeared across time and across cultures and to provide a context for thinking about pedophilia and sexual offending against children in modern societies. Some of these historical or cross-cultural examples are clearly relevant to pedophilia, involving prepubescent children, whereas others are less so, referring to adult sexual contacts with adolescent boys or girls.

Historical Evidence

Quinsey (1986) provided an early review of historical data on adult–child sex, and Killias (1991) described the Western history of laws against adult–child sex; for example, Roman law fixed the minimum age for marriage as 12 for girls and 14 for boys. Many of these girls and boys might have been prepubertal or pubertal in status in that age range. It should be noted, however, that many marriages took place to build family alliances and for financial/resource decisions, not necessarily for love or sexual desire (Clancy, 2012). An adult man might marry a 12- or 13-year-old girl for these nonsexual reasons rather than because he desired girls in that maturity range. In his review, Killias claimed the Middle Ages had no minimum age for marriage and that marital availability was instead based on physical maturity.

Probably the best-known historical example of adult–child sex was the custom in Ancient Greece of men taking young adolescent boys as lovers, as part of a mentoring relationship that Killias (1991) suggested was socially expected. Relationships with prepubescent boys were severely punished, suggesting that pubescent and postpubescent features were idealized. Some examples of child prostitution and adult–child sex date from the Byzantine and Roman Empires (Lascaratos & Poulakou-Rebelakou, 2000). Marriages involving children were frequently arranged for political and social reasons, but the couple was supposed to wait until the younger person had turned 12 to begin having sex.

In addition, some historical references to adult–child sex are non-Western. Lloyd (1976) and Ng (2002) noted ancient Chinese references to men having sex with boys (ages or pubertal status are unspecified), with a preference for effeminate boys rather than the masculine, athletic boys idealized by ancient Greek writers. Schild (1988) described Arabic literary references to sexual relationships between adult men and male youths as an alternative sexual outlet for men who were married and suggested that “the irresistible seductive power of beautiful youths is an often-repeated theme in Arabian and Persian poetry and literature” (p. 40). Again, puberty was an important demarcation because the sexual attractiveness of boys was considered to wane once boys had reached a certain degree of physical maturity.

One of the first clinical sexology descriptions of men who were sexually attracted to children was provided by von Krafft-Ebing (1906/1999). For example, Case 228 was a man who was sexually attracted to boys between the ages of 10 and 15, with no attraction to girls or to adults of either sex. This could represent pedophilia, hebephilia, or pedohebephilia. Von Krafft-Ebing thought pedophilia was rare because he had only seen four cases, all male, who he believed had a primary sexual interest in children. Anticipating the current understanding of nonpedophilic sexual offending against children, he thought that many cases of sexual contacts with children could be explained by boredom (e.g., hypersexual men seeking novelty), interpersonal deficits (e.g., men who were afraid of women or anxious about their sexual performance), or disinhibition because of intoxication or cognitive impairment (see

Chapter 4

, this volume).

Cross-Cultural Evidence

Most scientific evidence on pedophilia, hebephilia, and sexual offending against children has been gathered from Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, and some Western European countries. Much less is known about these topics from other countries. However, reliable data on rates of sexual offenses against children—a relevant behavioral indicator—have been gathered across all continents, including studies of Asia, Africa, and South America (Stoltenborgh, van IJzendoorn, Euser, & Bakermans-Kranenburg, 2011). The data showed substantial variation, with Africa producing the highest rates (eight samples of girls, five samples of boys) and Asia having the lowest rates (11 samples of girls, eight samples of boys). This indicates cross-cultural variation in the incidence of child sexual abuse and reporting practices.

Rind and Yuill (2012) reviewed ethnographic evidence on adult–youth sex, focusing on data involving pubescent children and adolescents because they were using these data to criticize the idea of including hebephilia in the

DSM–5

. They went into particular detail regarding evidence of sex between adult men and male youth, with 20th-century data from Albania, Libya, and tribal societies in Africa. Clear evidence indicates marriages of men with pubescent girls in the ethnographic record. It is also clear from Rind and Yuill’s review that adult interactions with prepubescent children are much less common, with exceptions being the Sambia in New Guinea, the Bossi of Burkina Faso, Javanese, and East Bay Islanders (Santa Cruz Islands). This again suggests that puberty is an important liminal event, marking the biological threshold for potential reproduction. Finally, Graupner (2000) claimed age of sexual consent laws are a recent invention, although he also claimed that sex with a prepubescent child has always been prohibited, whereas the legality of sex with postpubescent youth varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. I am not aware of any modern jurisdiction that has a legal age of consent lower than 12.

CHAPTER SUMMARY

The extent to which a phenomenon appears across time and across cultures says something about its universality and perhaps its origins as well. The available evidence suggests that adult–child sex has occurred historically and cross-culturally but is much more likely to involve pubescent or postpubescent youth. Puberty is critical, as indicated by minimum marriage ages and the punishment of sex with prepubescent children in many societies. Societies where sex with prepubescent children does take place involve delineated cultural practices, such as the Sambian practice of initiating boys into manhood through the ingestion of semen (Herdt, 1981).

A challenge is that adult interest or behavior involving prepubescent or pubescent children could exist but not be recorded because it is shameful or illegal, and thus hidden from historians or ethnographers. There is no theoretical or empirical reason, however, for expecting pedophilia, hebephilia, or sexual offending against children to be temporally or culturally bound, although it clearly varies as a result of environmental and other parameters; consider the cross-cultural variation in child sexual abuse rates reported by Stoltenborgh et al. (2011).

Pedophilia can be seen as a disturbance in the mechanisms underlying sexual age preferences, that is, as a maladaptive exaggeration of the male-typical preference for youthful features in potential sexual partners. Quinsey and Lalumière (1995) suggested pedophilia may represent a disorder, consistent with the definition by Wakefield (1992), in the mechanisms that regulate men’s sexual preferences for youthfulness. In other words, persons with pedophilia pay attention to youthfulness cues such as smooth skin and neotenous facial features, as other men do, but they do not attend to fertility cues such as a waist-to-hip ratio around .67 or firm breasts and buttocks. I further discuss this idea about the critical cues underlying pedophilic sexual interests in

Chapter 5

, this volume. Knowledge about the important psychological and physical cues of attractiveness could greatly inform efforts to understand pedophilia and hebephilia.

The second diagnostic criterion in

DSM–5

is substantial distress or impairment because of pedophilia. This distress or impairment can be the result of multiple factors, including personal distress at having an unwanted sexual interest in children; stress and psychopathology because of having a highly stigmatized sexual interest and thus having the burden of hiding one’s sexual interest; and getting into social or legal trouble as a result of acting on the interest, for example, by accessing child pornography or having sexual contacts with young children.

The argument about maladaptiveness is less clear for hebephilia (Spitzer & Wakefield, 2002), which is less rare than pedophilia. Rind and Yuill (2012) argued that cross-cultural and historical evidence of marriage to pubertal girls and sex between men and pubescent boys as a means of social bonding and mentoring argument suggests that the potential to sexually respond to pubescent children has adaptive functions. On the other hand, Hames and Blanchard (2012) reviewed evidence to suggest that having hebephilia is associated with lower reproduction (although see Rind, 2013, 2017), and I have suggested that the potential to sexually respond to pubescent children does not negate the possibility that individuals who have an exclusive or preferential attraction to pubescent children over sexually mature adults do show evidence of Wakefieldian dysfunction (Seto, 2017b). The evidence regarding marriage or other socially prescribed adult–pubescent-child sex is evidence of hebephilic behavior but is not necessarily evidence of hebephilic sexual preferences. Indeed, I think the key test of someone’s sexual attraction is choice: Would the person choose a prepubescent or pubescent child if a sexually mature person was available?

1

The ratio of waist and hip measurements.

2

A word from German authors who used it to describe pedophilic or hebephilic sexual behavior, respectively, which could include viewing relevant child pornography, masturbating to sexual fantasies about prepubescent or pubescent children, and engaging in sexual contacts with children in these maturity groups.