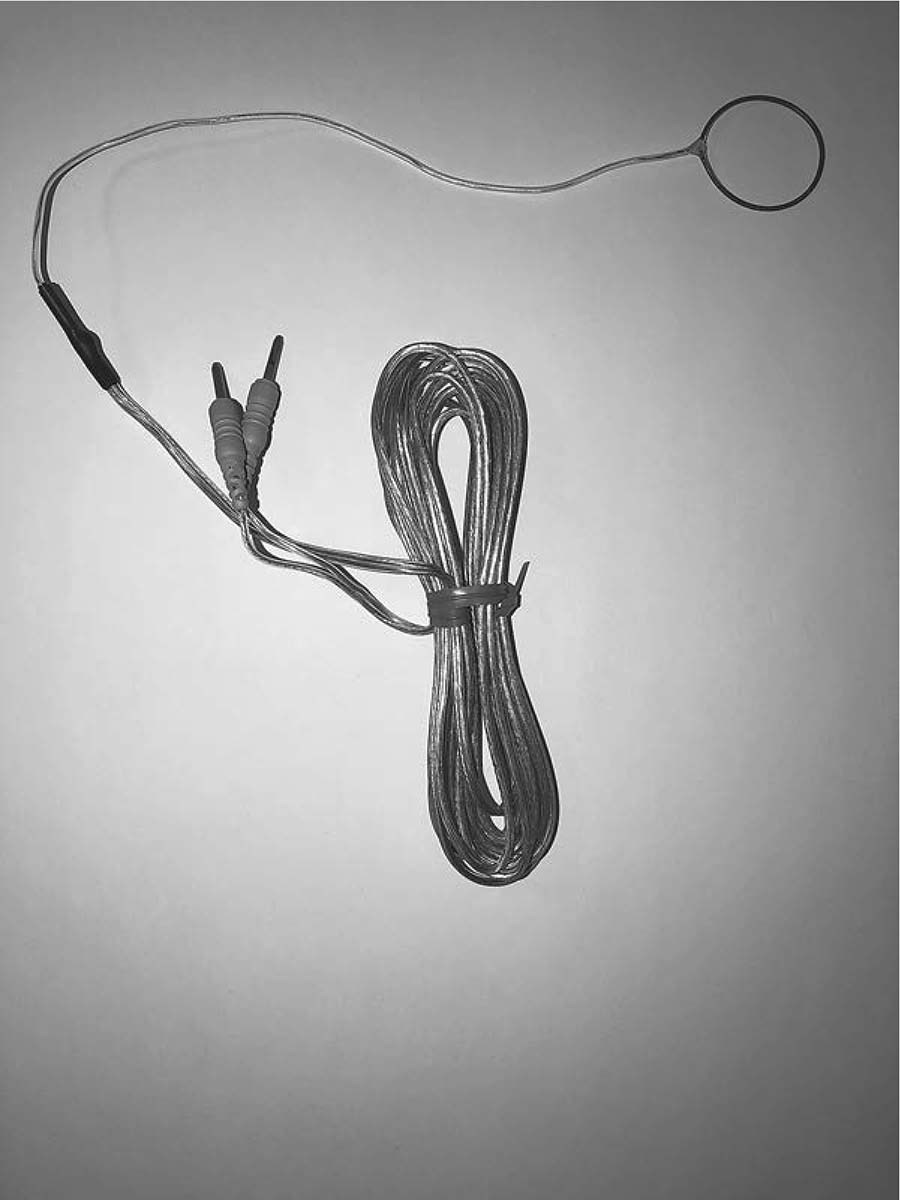

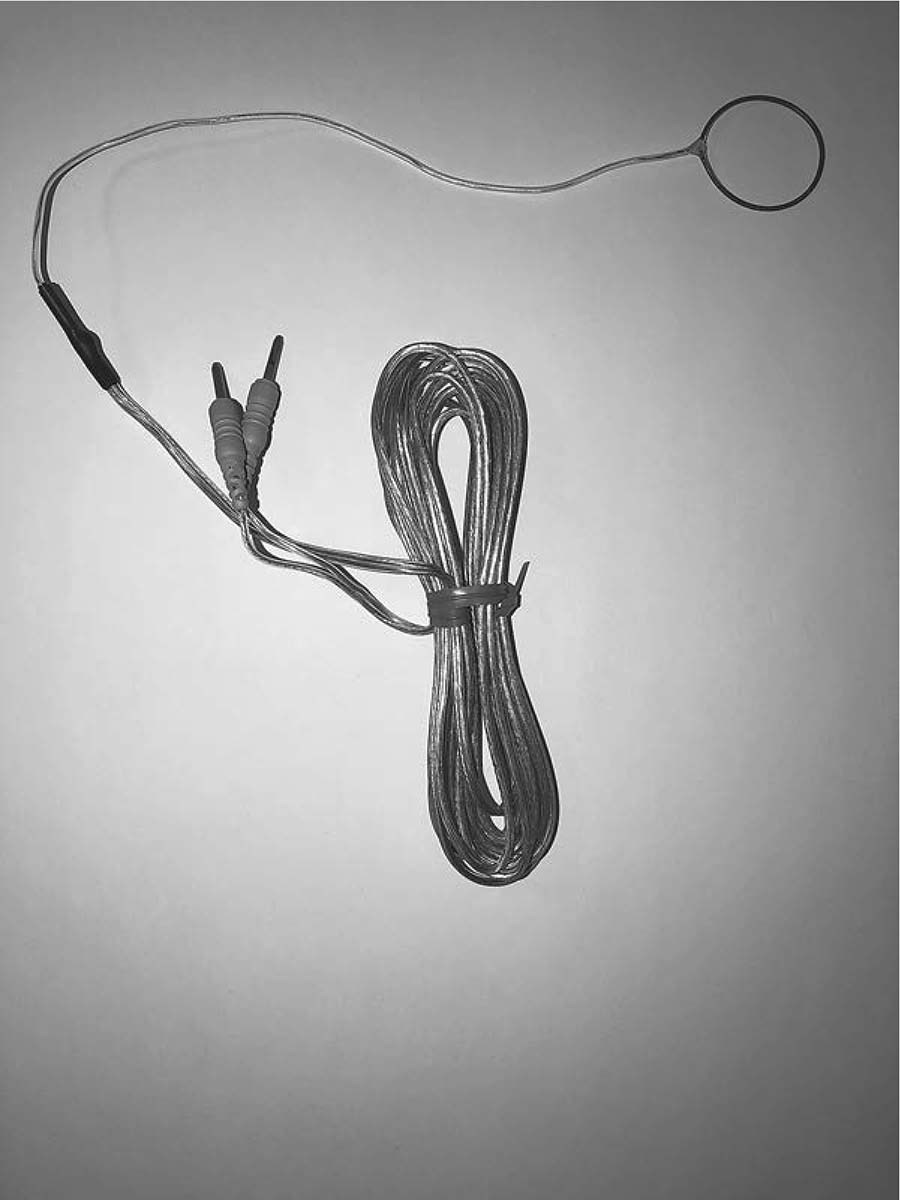

Figure 2.2.

Circumferential gauge for phallometric testing. From the Kurt Freund Phallometric Laboratory, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Copyright 2017 by the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. Reprinted with permission.

Relative rather than absolute phallometric responses are the most useful for analysis and interpretation because they take individual differences in penis size and responsivity into account (Harris, Rice, Quinsey, Chaplin, & Earls, 1992; Lykins et al., 2010). Responsivity can vary because of age, health, and other factors, such as time since last ejaculation. To illustrate, imagine someone who shows a 10-mm increase in penile circumference when he sees images of children: The meaning of this absolute change is clearer when one knows whether he shows a 5- or 20-mm increase in response to pictures of adults. The first pattern of responses is from someone who is more sexually aroused by children than by adults, and thus might be indicative of pedophilia. The second pattern is someone who is more sexually aroused by adults than by children but is overall more responsive in the phallometric laboratory.

As an assessment method that has been around for over half a century, there is substantial research on the discriminative, criterion-related and predictive validity of phallometric testing. As already noted, indices of relative phallometrically assessed sexual arousal to children significantly distinguish sex offenders against children from other men, wherein the offenders with child victims respond relatively more to children (e.g., Freund & Blanchard, 1989; Quinsey, Steinman, Bergersen, & Holmes, 1975). Phallometrically assessed sexual arousal to children is still the most reliably identified characteristic distinguishing sex offenders with child victims from other men.

Sensitivity and Specificity

At the level of individual diagnosis, well-known tests have demonstrated sensitivity and specificity at specified cutoffs, where

sensitivity

reflects the proportion of sex offenders against children who are correctly identified by having higher scores on the phallometric index, and

specificity

reflects the proportion of the nonpedophilic comparison group who are correctly identified by having lower scores on the phallometric index. An intuitive cutoff is a standardized index score of zero, which indicates when someone responds equally to children and adults. The phallometric lab at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (the source of many important phallometric studies) uses a more conservative cutoff of .25, which means only those who show a clear preference for children over adults would be considered to show a pedophilic sexual arousal pattern (Blanchard et al., 2001). The sensitivity and specificity of phallometric testing vary across laboratory and procedures, so results obtained at one laboratory may not reflect what would have been found in other labs (McGrath et al., 2010). Estimates of sensitivity are underestimates of diagnostic performance because not all offenders with child victims are expected to have pedophilia (or hebephilia); only some offenders have a child-focused chronophilia, with others committing offenses for nonpedophilic motivations, such as high sex drive or antisocial opportunism (see

Chapter 4

, this volume). For example, a study may find that 60% of a sample of sex offenders against children show a pedophilic sexual arousal pattern when assessed phallometrically, producing a sensitivity of 60%; however, the sensitivity is actually 66% if 90% of the sample was truly pedophilic, which is what Freund and Watson (1991) estimated on the basis of their clinical experiences in a forensic sexology service. The actual proportion that is pedophilic will in turn depend on the setting and sample selection criteria. For example, one might imagine a higher proportion of pedophilic sex offenders in a prison-based program for repeat offenders compared with a community assessment clinic for first-time incest offenders.

There is no accepted gold standard against which to evaluate phallometric testing. One option is to look at the sensitivity of the test among individuals who admit being sexually attracted to prepubescent children. Among this subgroup, sensitivity is very high. Across a series of three studies, Freund and colleagues examined the phallometric test results of 137 sex offenders against children who admitted to having pedophilia, and they found that sensitivity was 92% (Freund & Blanchard, 1989; Freund, Chan, & Coulthard, 1979; Freund & Watson, 1991). What researchers do not yet know is how well phallometric testing performs with nonoffending, self-identified persons with pedophilia.

Because of the clinical and forensic interest in phallometric test results, the greater interest is in how the test performs with offenders who deny having pedophilia. Another approach is looking at a selected sample of individuals who are likely to be pedophilic; this is the approach that Blanchard (2011) took, reporting the sensitivity and specificity across groups defined by number of child victims. Lykins et al. (2010) found the reliability of a phallometric diagnosis went up with overall arousal level, and results were therefore stronger if interpreting scores of 2.5cc or higher, corresponding to approximately 10% of the average full erection of 25 mm shown by 42 volunteers in Kuban, Barbaree, and Blanchard (1999). Because of the highly negative consequences—especially in legal proceedings—and stigma of being identified as having pedophilia (Jahnke, Imhoff, & Hoyer, 2015), cutoff scores are usually set so that the specificity is high (i.e., the inherent trade-off between specificity and sensitivity—a higher cutoff ensures higher specificity and lower sensitivity, and a lower cutoff ensures the converse).

To further illustrate the performance of phallometric testing, Freund and Watson (1991) found sensitivity of 50% at a cutoff score that produced 98% specificity in a sample of 147 sex offenders with unrelated child victims. Blanchard et al. (2001) found sensitivity of 61% among offenders with three or more child victims, at a cutoff that produced 96% specificity. Because specificity is predetermined to be higher than sensitivity, the presence of pedophilic sexual arousal is more informative than its absence. One can be confident that someone who shows this pattern of sexual arousal is likely to have pedophilia, whereas someone who shows an unremarkable pattern of sexual arousal might be truly teleiophilic or might be a false negative.

Cantor and McPhail (2015) reported on the sensitivity and specificity of phallometric testing specifically for hebephilia in a sample of 996 offenders with one or more extrafamilial child victims age 14 or younger—all of whom reported greater sexual interest in adults than in minors and denied pedophilia or hebephilia—and a comparison group of 239 offenders against adults only. Using the same volumetric phallometry procedure as reported by Blanchard et al. (2001) and Freund and Watson (1991), Cantor and McPhail found a sensitivity of 70% and specificity of 91% for hebephilia, compared with 47% sensitivity and 100% specificity for pedophilia. The latter was 72% sensitivity and 95% specificity when using a cutoff score of 0 as opposed to .25 as in previous studies. The authors interpreted these results as evidence that phallometry has diagnostic utility among individuals who have committed offenses against children between the ages of 11 and 14 but who deny hebephilia.

Using the clinic’s standard cutoff of a .25 standard deviation greater response to child than to adult stimuli, sensitivity was 75% and specificity was 91% for pedohebephilia in Cantor and McPhail (2015), which might be the more germane classification because interest in either prepubescent or pubescent children is a concern and the overlap between these two chronophilias is high (Stephens, 2015). Sensitivity increased as number of extrafamilial child victims increased, from 36% for those with one such victim to 46% for two or three such victims to 75% for those with five or more child victims. It should be noted that Cantor and McPhail did not include offenders with intrafamilial victims only and did not include intrafamilial child victims in the victim counts. This could influence their sensitivity and specificity estimates given pedohebephilia is less common in intrafamilial offenders (see Barbaree & Marshall, 1989, and

Chapter 6

, this volume). At the same time, the victim counts included noncontact victims, where some of the motivation might involve exhibitionism or voyeurism rather than pedophilia, where the activity paraphilia may “overwhelm” age preferences (e.g., exposing to a 11-year-old girl even though the perpetrator prefers adult women).

Sensitivity and specificity estimates might be affected by other factors as well, including the type of penile measure used and the quality and number of stimuli used. Discrimination is probably highest with moderately intense sexual stimuli, because highly intense stimuli, such as sexually explicit videos with sound, can produce high responses from everyone, resulting in a statistical ceiling effect, whereas weak stimuli, such as nonexplicit erotic stories, can produce low responses that lead to a statistical basement effect. Images of real children are illegal in the United States under current child pornography laws (Canada has an exemption for clinical purposes), and some clinicians may object to the use of such stimuli for ethical reasons.

Criterion-Related Validity

I noted earlier that phallometrically assessed sexual arousal to children is related to child victim characteristics, such as gender, number, age, and relatedness, both in the SSPI studies and in previous studies. These associations have specificity: For example, offenders with boy victims respond more to stimuli depicting boys and offenders with girl victims respond more to girls (G. T. Harris, Rice, Quinsey, & Chaplin, 1996; Quinsey et al., 1975). Evidence also indicates that phallometric testing has validity for other paraphilias, including biastophilia (coercive sex; G. T. Harris, Lalumière, Seto, Rice, & Chaplin, 2012; Lalumière, Quinsey, Harris, Rice, & Trautrimas, 2003), sexual sadism (Seto, Lalumière, Harris, & Chivers, 2012), sexual masochism (Chivers, Roy, Grimbos, Cantor, & Seto, 2014; Seto & Kuban, 1996), and exhibitionism (W. L. Marshall, Payne, Barbaree, & Eccles, 1991). In principle, a phallometric test could be designed for any paraphilia, if the right stimuli were created and presented to the appropriate target and comparison groups, using validated assessment procedures.

Predictive Validity

Phallometrically assessed sexual arousal to children is one of the strongest predictors of sexual recidivism among sex offenders, producing a correlation similar to that found for psychopathy among sex offenders or for prior criminal history and general recidivism in other offenders (Gendreau, Little, & Goggin, 1996; Hanson & Morton-Bourgon, 2004, 2005). However, not all studies find this effect, and Stephens (2015) suggested that it may be tests that include violent sexual stimuli involving children that produce larger effects. In Stephens, Cantor, et al. (2017), we found a significant predictive effect for phallometrically assessed sexual arousal to children but only for noncontact sexual recidivism in a mixed sample of contact and noncontact offenders. We looked specifically at sexual arousal to prepubescent children, pubescent children, and the combination, and found no difference.

Criticisms of Phallometry

Despite the advantages of phallometry as an objective measure of pedophilic sexual interests that has discriminative, criterion-related and predictive validity, phallometry has been criticized for practical and ethical reasons.

Methodological Objections.

These objections include the lack of standardization in equipment, procedures, stimuli, and analysis that I noted above, although this is more a criticism of practitioners rather than of the method itself. A big problem for interpreting phallometric data, both clinically and for research, is this lack of standardization. A lack of significant findings might reflect the absence of a real effect, but it also might reflect poor phallometric procedures. Many laboratories do not use validated procedures and scoring methods, and this should be kept in mind when considering phallometric test results. Some procedures have been validated and so the reliability and validity of the results are known. Despite repeated calls for standardization in the field, little progress has been made. Evidence-based guidelines address many of these concerns, such as the number and type of stimuli to use and optimal transformations of phallometric data for interpretation (Lalumière & Harris, 1998; Quinsey & Lalumière, 2001).

Phallometric testing has been criticized because traditional internal consistency and test–retest reliability analyses suggest it is moderately reliable, at best (Barbaree, Baxter, & Marshall, 1989; Davidson & Malcolm, 1985; Fernandez, 2002; but see Gaither, 2001, for an opposing view). Given validity is constrained by reliability, and evidence that phallometric testing has validity, then it must be the case that traditional reliability analyses do not accurately reflect the psychometric properties of this method. It also suggests that increasing the reliability of phallometric testing would increase the validity effects that have been obtained.

It is true that phallometry is intrusive, given it requires participants to partially undress, place a device on or around their penis, and have their erectile responses recorded while a laboratory technician monitors the session. In some labs, the participant is observed using a camera trained on the upper part of their body, to reduce attempts to fake responses by looking away or tampering with the equipment.

Phallometric testing is clearly more intrusive than self-report or measures based on sexual victim or other offense history. But my view is still that phallometric testing provides valuable information that cannot otherwise be obtained. It can identify pedophilia in men who deny any sexual interest in children or have no known history of child pornography viewing or sexual contacts with children, and it is not redundant with admission of pedophilia because phallometric scores—reflecting the relative strength of the interest—are predictive of sexual recidivism and thus important for risk assessment and treatment (see

Chapters 7

and

8

, this volume). For example, two sex offenders with child victims may both admit to having sexual fantasies about prepubescent children, but only one of these men shows substantially more sexual arousal to children than to adults when assessed phallometrically: All other things being equal, the man who shows relatively more sexual arousal to children is at higher risk to sexually offend again.

Ethical Objections.

The first of two main ethical objections to the use of phallometry is that presenting stimuli depicting real children is unethical because the children usually did not provide informed consent (as in the case where some labs use child pornography images seized by police), and the second is that exposure to such images may have adverse effects on the participants, such as providing new content for sexual fantasies and rumination, particularly for adolescents who have sexually offended or first-time offenders. This first objection can be addressed by the use of created content, as in audiorecorded stories or the use of virtual child images such as the Not Real People set (Banse et al., 2010; Laws & Gress, 2004; Mokros et al., 2010). This is required in the United States because current child pornography laws do not exempt clinicians or other professionals from possessing content depicting real children, whereas in Canada, possession of child pornography is permitted under a clinical or research exemption.

Regarding the second ethical objection, my view continues to be that even first-time offenders who are clinically assessed using phallometry have already engaged in illegal sexual behavior and the potential benefit of the information obtained is greater than the possible cost. Moreover, any costs would be expected to be ameliorated in subsequent treatment participation or even a short debriefing. Although comparable studies have not been conducted with offenders, research on the sexual arousal of nonoffending volunteers has shown that any negative effects of exposure to stimuli depicting rape is offset by debriefing (Malamuth & Check, 1984).

Researchers have greater reluctance about using phallometry for adolescents who have sexually offended than for adults, usually expressed as concern about putting adolescents through the procedure, exposing them to sexually explicit stimuli, or negotiating assent and parent/guardian consent for younger adolescents. I still think phallometry is valuable for older adolescents who can consent to the procedure. Although limited, phallometric research on adolescents suggests fewer show “pedophilic” sexual arousal than their adult counterparts but some show a distinctive pattern of greater sexual arousal to children than to adolescents or adults (M. C. Robinson, Rouleau, & Madrigrano, 1997; Seto, Lalumière, & Blanchard, 2000). Moreover, phallometric responding is related to sexual victim history and to sexual recidivism in expected ways among adolescents who have sexually offended (Clift, Rajlic, & Gretton, 2009; Seto et al., 2003).

Neuroscanning

An interesting avenue to pursue in foundational research—if not yet practical for clinical uses in terms of access or cost—is the use of neuroscanning methods, such as computerized tomography (CT), positron emission tomography (PET), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or electroencephalography (EEG). Neuroscanning research in pedophilia and sexual offending against children builds on earlier work showing differential responding for sexual versus nonsexual activity (e.g., Karama et al., 2002; Park et al., 2001; Redouté et al., 2000; Stoléru et al., 1999) or distinguishing straight and gay male participants (Ponseti et al., 2006).

A number of teams have explored the possibility of finding structural (CT, MRI) or functional differences (PET; functional MRI [fMRI], EEG) in individuals who are pedophilic versus those who are not. Some researchers have a particular interest in testing neurobiological hypotheses about the etiology of pedophilia or the origins of sexual offending against children (see

Chapters 4

and

5

, this volume). Neuroscanning methods could provide an assessment that is harder to fake than phallometry or cognitive science tasks and is less dependent on sexual offense history or self-report bias. Ponseti et al. (2015, 2016) have recently suggested that face processing can distinguish offenders from nonoffenders with high sensitivity and specificity, obviating the need to show the nude bodies of children. This kind of assessment method is not practical for routine clinical use at this time, given costs and the need to validate these findings, but it suggests a promising direction for further research to understand the neurobiological substrates of pedophilia and as a potential option as the technology evolves and becomes more affordable.

A more affordable and therefore potentially more scalable approach involves the use of EEG. Prior studies have been conducted to see whether sex offenders and controls showed activity differences (e.g., Flor-Henry, Lang, Koles, & Frenzel, 1991). A recent study examined the potential of using EEG to record event-related potentials (ERPs) when exposed to sexual versus neutral stimuli (Knott, Impey, Fisher, Delpero, & Fedoroff, 2016). In this study, 22 pedophilic men were compared with 22 controls in their ERPs to images drawn from the International Affective Picture System (Lang, Bradley, & Cuthbert, 2008), not images involving children or images involving sexually explicit content. ERPs between the two groups had no differences except for a significantly attenuated and slower early frontal positive (P2) component that can start as early as 185 ms after stimulus onset. This ERP was not correlated with the arousal ratings of pedophilic participants but did correlate negatively with their scores on a measure of attitudes about children and sex.

DIAGNOSIS OF PEDOPHILIC DISORDER

The next issue to consider is how to use assessment information in the diagnosis of pedophilic disorder under

DSM–5

or the diagnosis of pedophilia under

International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problem

(10th rev. [ICD–10]), soon to be revised with ICD–11. Although some methods for assessing pedophilia are reliable and valid, surprisingly little research has been conducted on the reliability and validity of the diagnosis. Blanchard (2011) reviewed this literature as part of his contributions to the

DSM–5

paraphilias workgroup and found few studies on the reliability of the diagnostic criteria for pedophilia in the

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

(fourth ed., text rev. [

DSM–IV–TR

]; American Psychiatric Association, 2000) and none for proposed

DSM–5

criteria. As noted in

Chapter 1

, the

DSM–IV–TR

criteria were retained in

DSM–5

, except for a distinction between ascertaining pedophilia and diagnosing pedophilic disorder, where the diagnosis involves the presence of significant distress or impairment because of the sexual interest in children.

Reliability of Diagnosis

Levenson (2004a) found the interrater reliability for the diagnosis of pedophilia was acceptable in a sample of 295 adult male sex offenders, three quarters of whom had committed sexual offenses against minors. In an extension of this work, Packard and Levenson (2006) found better interrater reliability (kappa

1

of .65, 85% agreement) in

DSM–IV–TR

diagnosis of pedophilia in a sample of 277 sex offenders assessed in high-stakes, adversarial legal proceedings. A more recent study found similar diagnostic agreement (kappa of .72, 88% agreement) across clinicians for 25 sex offenders with child victims (R. J. Wilson, Abracen, Looman, Picheca, & Ferguson, 2011). Seto, Fedoroff, et al. (2016) examined the interrater reliability and criterion-related validity of the

DSM–IV–TR

and proposed

DSM–5

criteria (at the time the study was initiated) in a sample of 79 men assessed because of concern about their sexual interest in children, most because of criminal charges or convictions for contact sexual offenses against children and/or child pornography offenses. Kappa was .59 (81% agreement) for the

DSM–IV–TR

criteria and .52 (76% agreement) for the proposed

DSM–5

criteria.

Validity of Diagnosis

R. J. Wilson et al. (2011) found weak associations across different methods of assessing pedophilia—sexual history, checklist of

DSM–IV–TR

criteria, phallometric testing, and expert diagnosis—in a sample of sex offenders against children. Similarly, Moulden et al. (2009) examined

DSM

diagnosis, phallometric test results,

DSM

diagnosis plus phallometric results, and sexual victim history using the SSPI (Seto & Lalumière, 2001) in a sample of 206 men who had sexually offended against an unrelated child. Only phallometric test results involving sexual arousal to depictions of sexual assaults against children were significantly associated with sexual recidivism. Moreover,

DSM

diagnosis was not significantly correlated with sexual victim history or phallometric results. In a more recent study of 130 sex offenders with child victims, R. J. Wilson et al. found that

DSM–IV–TR

pedophilia diagnosis was not significantly correlated with phallometric results or with sexual recidivism. In our recent field trial,

DSM–IV–TR

diagnosis of pedophilia (i.e., pedophilic disorder in

DSM–5

) was significantly and positively associated, as expected, with a phallometric index of sexual arousal to children and to viewing-time results.

CHAPTER SUMMARY

The major assessment approaches, and their advantages and disadvantages, are summarized in

Table 2.2

. Although pedophilia can most easily be assessed through self-report, people have obvious reasons to deny or minimize sexual interest in children, especially because of legal or other consequences of self-identifying as having pedophilia (e.g., Jahnke, Schmidt, Geradt, & Hoyer, 2015). Because of this self-report bias, admission of sexual thoughts, fantasies, urges, arousal, or behavior involving prepubescent children is informative, whereas denial of such is less so. Other assessment methods have been developed because of the vulnerability of self-report. Polygraph interviewing can increase disclosures, likely because of the bogus pipeline effect, but the potential for false disclosures as a result is unknown.