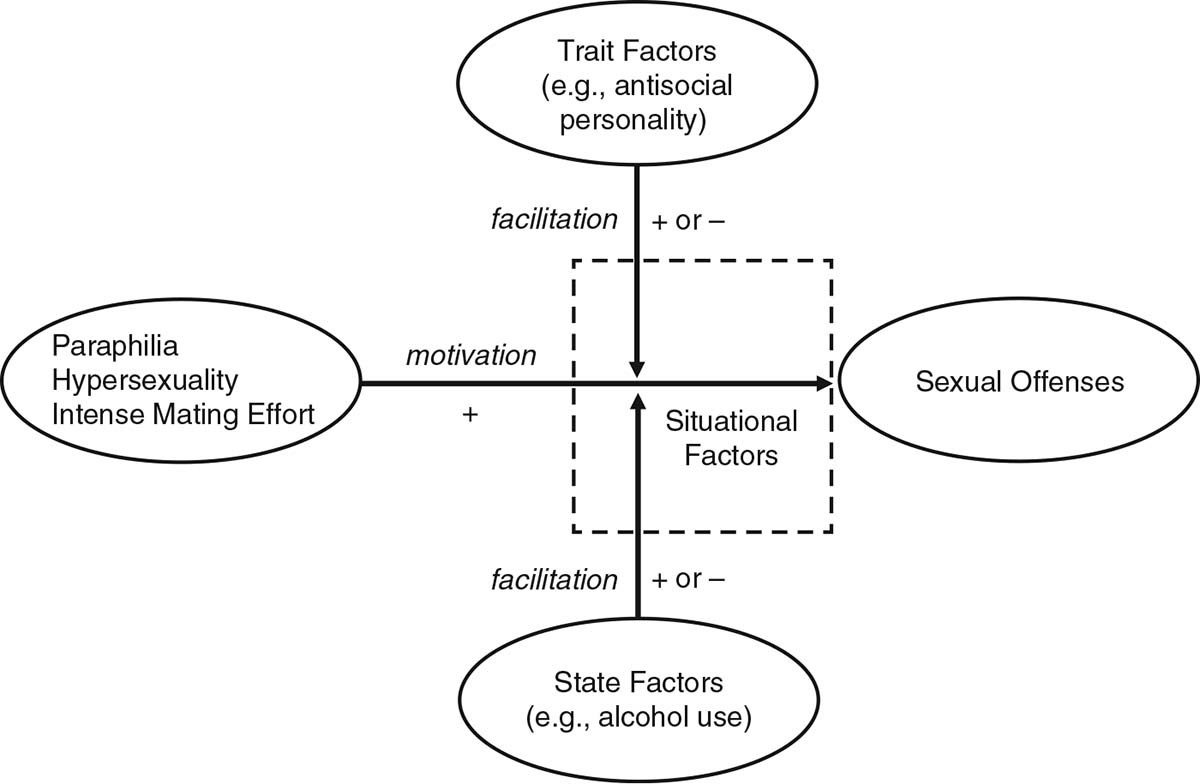

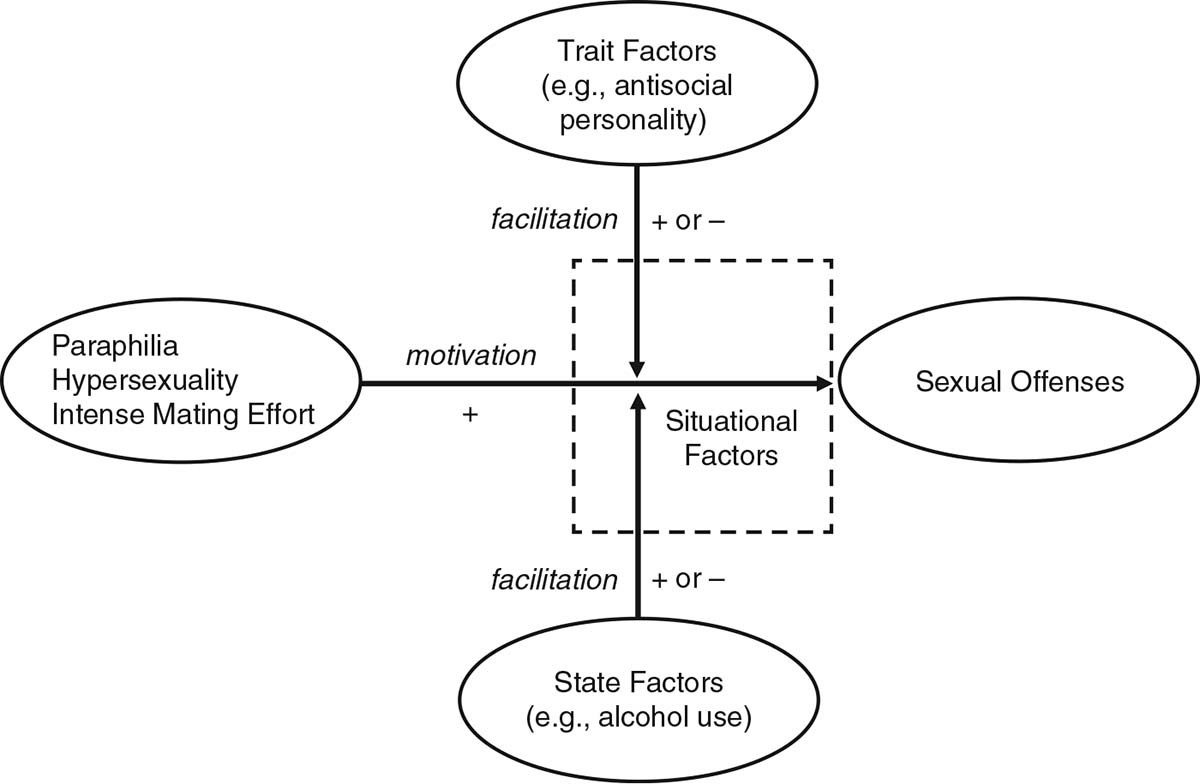

Figure 4.1.

The motivation facilitation model. From “The Motivation-Facilitation Model of Sexual Offending,” by M. C. Seto, 2017, Sexual Abuse

[advance online publication, p. 3]. Copyright 2017 by Sage. Adapted with permission.

ONSET VERSUS PERSISTENCE

An important question for this and all the other models described in this chapter is how well what researchers know about the factors associated with sexual reoffending by identified sex offenders reflects what distinguishes those who commit sexual offenses from those who do not. Different study designs are required: Onset research requires following (at-risk) individuals to see who commits sexual offenses in the first place and comparing sex offenders with other offenders and with nonoffenders, whereas persistence research involves following identified sex offenders to see who reoffends and comparing recidivists with nonrecidivists.

Motivations to sexually offend vary from offender to offender and sometimes even from offense to offense, but the motivation–facilitation model expects three major types of motivations: (a) paraphilic sexual interests, such as pedophilia, for many sexual offenses against children (see

Chapters 1

and

2

, this volume); (b) hypersexuality, as reflected in excessive sexual preoccupation and excessive engagement in fantasy, masturbation, and pornography use, as in the case of sexual solicitation offenders who approach both teens and adults online and also engage in many other forms of online sexual behavior (e.g., cybersex chats); and (c) intense mating effort, which reflects an exaggerated pursuit of novel and casual sexual liaisons that sometimes involve sexual coercion. Intense mating effort can account for many acquaintance sexual assaults against teens or adults.

The motivation–facilitation model does not specifically consider nonsexual motivations, such as anger against women or desire for control, unless these motivations are sexualized, for example, when anger against women is expressed through sexual arousal to women’s cues of nonconsent or physical suffering. Strictly nonsexual motivations, such as anger, are instead expected to be expressed as nonsexual behavior, such as nonsexual assaults or other aggression.

Paraphilic Motivations

Paraphilias were the first type of sexual motivation to be considered in the motivation–facilitation model, with pedophilia as the focus of Seto’s (2008) description. Since then, the paraphilias component has been expanded to include

hebephilia

(sexual interest in prepubescent children),

biastophilia

(coercive sex),

sexual sadism

(causing suffering or humiliation),

exhibitionism

(exposing one’s genitals to an unsuspecting stranger), and

voyeurism

(surreptitiously viewing an unsuspecting stranger undressing or engaging in other normally private behavior; Pullman et al., 2016).

Hypersexual Motivations

Not all sexual offenses are motivated by paraphilias. Some sexual offenses are explained instead by excessive or abnormally intense sexual preoccupation that is not satisfied by legal behavior, such as pornography use, masturbation, and pursuit of casual sex. Instead, the hypersexual person turns to criminal sexual behavior involving persons who do not consent or cannot legally consent, including paraphilia-like behavior involving exhibitionism, voyeurism, or pedohebephilia (see Kafka’s, 2003, notion of paraphilia-related disorders). Kuhle et al. (2017) found that sexual preoccupation distinguished self-identified pedophilic or hebephilic individuals who had committed both child pornography and contact sexual offenses from those who had committed child pornography offenses only.

Mating Effort Motivations

Mating effort is similar to hypersexuality in that it encompasses individuals who are not paraphilic but turn to criminal sexual behavior involving persons who do not consent or cannot legally consent. However, unlike

hypersexuality

, which refers to excessive or abnormally intense sexual preoccupation or sex drive,

mating effort

refers to how that sexual preoccupation or drive is directed. Hypersexuality could be directed toward both familiar and novel sexual partners; by definition, mating effort is directed toward novel sexual partners. Intense mating effort is implicated in a substantial proportion of offenses involving older adolescents and adults (Lalumière et al., 2005).

Facilitation

Facilitation factors increase the likelihood that a sexual motivation is acted upon. According to the motivation–facilitation model, motivation is a necessary but not sufficient condition for sexual offending, because individuals vary in their willingness or ability to act on those motivations. For example, pedophilic individuals high in self-control who are law abiding would resist their sexual attraction to a particular child, whereas someone who was more impulsive, more reckless, and less concerned about negative consequences would be more likely to act if given the opportunity. Facilitation usually plays some role because even the most chronically disinhibited individuals (e.g., because of serious, chronic cognitive impairment) do not act indiscriminately across time and space.

The motivation–facilitation model considers both trait and state facilitation factors.

Traits

are individual differences associated with the propensity to engage in antisocial behavior, such as antisocial personality traits, antisocial attitudes and beliefs, and poor self-regulation skills. These traits are stable over time, especially in terms of relative rank (e.g., someone who is at the 99th percentile on measures of antisocial personality might score lower as he ages, but he is still expected to have a much higher score than the average person).

State

facilitation factors are more dynamic over time, such as alcohol or drug intoxication or strong emotions (e.g., anger).

Individuals with pedophilia, hypersexuality, or intense mating effort and who are disinhibited are more likely to act on their sexual motivation to engage in sexual behavior directed toward children. Moreover, these motivations are not mutually exclusive: Someone could have pedophilia, hypersexuality, and intense mating effort; such a person might be at particularly high risk of sexually offending against children because of their attraction to children, excessive sexual preoccupation about children, and preference for child novelty.

Individuals who are high in motivation and who do not have sufficient trait or state inhibition are more likely to sexually offend when they have opportunities; they are also more likely to seek out opportunities to commit sexual offenses. At the same time, even strongly experienced motivations to sexual offend with ample opportunities to offend can be blocked if facilitation factors are absent or weak. The effects of motivation and facilitation factors might interact, such that individuals who are high in both are much more likely to sexually offend or reoffend (Hildebrand, de Ruiter, & de Vogel, 2004; Rice & Harris, 1997; Seto, Harris, Rice, & Barbaree, 2004; although see contrary results in Olver & Wong, 2006, and Serin, Mailloux, & Malcolm, 2001).

The motivation–facilitation model was built from research involving clinical and criminal justice samples but also includes research conducted with men in the community, including pioneering work by leading researchers, such as Antonia Abbey, Mary Koss, Martin Lalumière, and Neil Malamuth in explanations of sexual offending by men against women. A study by Klein, Schmidt, Turner, and Briken (2015) with a large German sample of men recruited by a marketing organization to be population representative in terms of their age and education found self-reported contact sexual offending against children was correlated with self-reported sexual fantasies about children and antisociality (as indicated by convictions for nonsexual offenses), as predicted by the motivation–facilitation model. Moreover, self-reported child pornography use was related to sexual fantasies about children, sex drive, and antisociality. Contact sexual offending was moderately correlated with pedophilic fantasies and less so with antisociality; similarly, child pornography offending was moderately correlated with pedophilic fantasies and weakly correlated with antisociality. The likelihood of contact sexual offending exceeded 15% when someone was both high in pedophilic fantasies and antisociality, compared with less than 2% for those low on both measures. These results can be compared with Duwe (2012), who found that antisociality predicted the onset of sexual offending among general offenders released from prison. However, the cross-sectional survey by Klein et al. (2015) cannot exclude the possibility that the sexual offenses occurred first, followed by fantasies regarding the experiences, because timing was not explicitly addressed.

Earlier Models, Revisited

I ended the last section with a summary of the similarities and differences across theories. All these theories recognize that sexual offending has motives, and all recognize factors that can facilitate acting on these motivations. Where the models differ includes whether motivations can be nonsexual in nature and whether paraphilias or hypersexuality are specifically included. Evaluations of the motivation–facilitation model and other models await longitudinal studies of general or at-risk cohorts of children and young adolescents, to see whether the model explains the onset of sexual offending (as opposed to the persistence of it). Such studies are very expensive and difficult to carry out, but they are essential to understand the origins of sexual offending.

Seto (2017a) reviewed the evidence for and against the motivation–facilitation model, with a particular emphasis on identifying major gaps. This review pointed to future research needed to test the model, possibly modify it, and to fill in those gaps. This includes research with self-identified perpetrators, using anonymous online surveys with community samples. A recent example was reported by Mitchell and Galupo (2016), who recruited 100 men admitting sexual interest in children for an online survey on protective factors. Most participants were primarily attracted to children between the ages of 7 and 13 (37% to boys, 43% to girls, 4% to both), whereas a minority were attracted to boys or girls under the age of 7. Of Mitchell and Galupo’s respondents, 69% reported they had never acted on their sexual interest in children. This group was compared with the 31 respondents who admitted acting on their sexual interest in children in their responses to questions about five brief vignettes describing sexual interactions with a child (age and gender ambiguous). Respondents were asked about their hypothetical sexual arousal to the description (“In this situation, how sexually aroused would you be?”), behavioral propensity (“In this situation, would you have fondled the child?”), and general enjoyment (“In this situation, how much would you enjoy getting your way?”) to scenarios differing in the amount of force described. Those who had never acted scored lower on behavioral propensity, which may reflect both lower motivation and lower facilitation.

Bailey, Bernhard, and Hsu (2016) conducted an online survey of 1,102 men who self-identified as being attracted to children with questions about adjudicated offenses involving child pornography or sexual contacts with children. They avoided questions about undetected sexual offenses, thereby avoiding the potential concern of self-incrimination. The base rate for being arrested of child pornography was 9%, and the corresponding rate for sexual contacts with children was 8%. Fifteen percent had been adjudicated for either sexual offense. It is safe to assume that the actual offending rates were higher because many offenses do not result in arrest. The strongest correlate of adjudicated offending was age, probably reflecting both opportunity to offend and opportunity for any offending to be detected. Indeed, the rate of being adjudicated for either sexual offense was over 40% in the oldest age group of men, age 56 or older, which could reflect cumulative opportunity and/or cohort effects in the likelihood of sexually offending. Controlling for age, being attracted to boys was also associated with a greater likelihood of sexually offending. Other correlates were being older, working with children, falling in love with a child, relative attraction to children versus adults, and struggling to refrain from offending. Having children of one’s own was significantly associated with adjudicated offending but not after controlling for age. This does not necessarily mean any sexual offenses involved participants’ children, as having children would also increase contacts with unrelated children. Consistent with the motivation–facilitation model, these can be understood as factors associated with motivation (relative attraction to children, attraction to boys), opportunity (age, working with children), or with facilitation (difficulties with self-control). Falling in love with a child could be seen as a correlate of sexual attraction to children. Surprisingly, permissive attitudes about adult–child sex and frequent sexual fantasies about children were not correlated with sexual offending, whereas sexual abuse history was.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of the motivation–facilitation model include parsimony, testability, and its integration of existing evidence regarding the onset or persistence of sexual offending. It is consistent with tenets of other major explanations of sexual offending against children but differs in its emphasis on sexual motivations and the facilitation of acting on those motivations. The most recent iteration also recognizes the role of situational factors having to do with opportunity and access to potential child victims (Seto, 2017a; Stephens, Reale, Goodwill, & Beauregard, 2017). The motivation–facilitation model can be viewed as an extension of low self-control theory and of Finkelhor’s (1984) preconditions model.

The motivation–facilitation model also has limitations. Most research on sexual motivations for sexual offending against children has specifically focused on pedophilia. However, hebephilia is a relevant and distinct sexual interest in pubescent children and is likely to play a major role in sexual offending against older but preadolescent children (Stephens, 2015). Indeed, there may be more hebephilic than pedophilic offenders (Seto, 2017b). Also, little work has examined the role that hypersexuality might play in offending against children. Some empirical support indicates the use of sex-drive-reducing medications for some pedophilic offenders with a history of feeling unable to control their sexual urges (Rice & Harris, 2011; Thibaut et al., 2010; see also

Chapter 8

, this volume), but this option does not require hypersexuality, as even turning down normal sex drive can reduce sexual fantasy and behavior.

Researchers do not have much empirical evidence regarding the motivation–facilitation model with adolescents who have sexually offended or with women sex offenders. The evidence is limited on the role of pedophilia, for example, with some case series for female sex offenders and some phallometric and viewing-time evidence that a minority of adolescents, particularly those who offend against younger boys, show relatively greater sexual interest in children than their adolescent counterparts (Seto, Lalumière, & Blanchard, 2000; Seto, Murphy, Page, & Ennis, 2003).

An important avenue to pursue is experimental work to manipulate motivation and facilitation factors to see what effects that might have on self-reported propensity to sexually offend or a behavioral proxy, for example, drawing from the cognitive science measures described in

Chapter 2

. There has been a relative dearth of experimental studies following up on early work from the 1970s and 1980s looking at factors such as the impact of preexposure to pornography or anger on subsequent sexual arousal to depictions of rape. A recent example is a mood induction study by Lalumière, Fairweather, Harris, Suschinsky, and Seto (2017), which found that induction of positive or negative mood facilitated sexual responding to depictions of sexual coercion in the lab. Concomitant work on what affects sexual arousal to children, self-reported propensity to view child pornography or seek sexual contacts with children, or implicit responses to child stimuli would be very informative.

DEVELOPMENTAL CRIMINOLOGY

As noted earlier, a relatively recent development in the sexual offending field is the emergence of developmental life course models and studies that incorporate evidence about criminal versatility, developmental trajectories in antisocial and criminal behavior, and factors identified in general criminology (Lussier & Cale, 2013; Smallbone & Cale, 2015). Evidence supports both generalization and specialization in sexual offending, wherein some sex offenders show a versatile criminal career and others are more specialized, for example, committing repeated noncontact sexual offenses, such as online child pornography (Howard, Barnett, & Mann, 2014) or repeated sexual offenses against children, especially boys (Butler & Seto, 2002; Hanson, Scott, & Steffy, 1995).

Several of the theories reviewed here share a developmental perspective (W. L. Marshall & Barbaree, 1990; W. L. Marshall & Marshall, 2000; Ward & Beech, 2006). The motivation–facilitation model is relatively silent about development, but the original articulation in Seto (2008) highlights potential factors in the etiology of pedophilia (see

next chapter

, this volume) and considers facilitation factors within developmental criminology, including Moffitt’s (1993) distinction of life-course-persistent and adolescence-limited delinquency and the cumulative risks toward antisocial and criminal behavior (Seto & Barbaree, 1997).

Although each developmental transition has substantial discontinuity, the associations are moderate to strong between childhood sexual behavior problems, adolescent sexual offending, and adult sexual offending, respectively. Retrospective studies suggest approximately half of adult sex offenders committed their first sexual offense as an adolescent; similarly, up to half of adolescent sex offenders have engaged in problematic sexual behavior as children under the age of 12 (Abel, Osborn, & Twigg, 1993; Burton, 2000; Zolondek, Abel, Northey, & Jordan, 2001). Prospective studies, however, show that only a minority of children with sexual behavior problems go on to commit sexual offenses as adolescents, and again a minority of adolescents who have sexually offended commit another sexual offense as an adult (Caldwell, 2016; Carpentier, Silovsky, & Chaffin, 2006). In other words, most children with sexual behavior problems and most adolescent sex offenders desist, although they may continue to engage in some nonsexual criminal or antisocial behavior. The majority of adult sex offenders desist too. However, a small group of individuals persist and sexually offend again.

For many children, their sexual behavior problems may represent a transient reaction to the sexual abuse they experienced (Salter et al., 2003). Other cases can be explained in terms of sexual precocity or normative sexual experimentation; for example, children sometimes expose their genitals in public, and whether this is labeled a sexual behavior problem depends in part on who detects them, where this takes place (e.g., school policies may oblige teachers to report genital exposure), and the child’s developmental history and family context. For many adolescents, their sexual offenses represent the confluence of adolescence-limited risk taking and delinquency, a rapid increase in sex drive accompanying the onset of puberty, and opportunism. Indeed, I and my colleagues have described a developmental model of sexual offending that draws heavily on Moffitt’s (1993) distinction between life-course-persistent and adolescence-limited trajectories (Lalumière et al., 2005; Quinsey, Skilling, Lalumière, & Craig, 2004; Seto & Barbaree, 1997).

Moffitt (1993) referred to a developmental taxonomy that distinguished between different groups of delinquents, each with different causes and developmental trajectories. As the label would imply, the life-course-persistent group engage in antisocial behavior early in life, continue through adolescence, and persist into adulthood. In contrast, the adolescence-limited group is much larger and most of its delinquency is restricted to the adolescent years, when risk taking, peer influences, and opportunities collide. The life-course-persistent group is characterized by neuropsychological difficulties and early adversities, such as family instability and abuse or neglect. Although they are a small minority of the population, perhaps 5%, they account for a disproportionate amount of crime because they start early, offend frequently, and persist over time. Moffitt (1993) suggested that this 5% of the population accounted for 50% of crime.

Early adversities may represent environmental effects that increase risk of life-course-persistence or heritable predispositions because life-course-persistent parents are more likely to have family instability and to commit acts of abuse or neglect. Whether environmental or genetic, the initial differences in neuropsychological functioning and family environment interact in cumulative processes that make it harder and harder to desist from antisocial behavior and to instead engage in prosocial behavior. For example, early peer rejection and academic failure reduce social and employment opportunities later in life, making a criminal life more likely.

The adolescence-limited group is much larger and does not have the same early risk factors; indeed, they are normative. They will mimic, however, the life-course-persistent individuals in their midst; although not necessarily liked, life-course-persistent individuals achieve status indicators that their peers do not yet have, including money (e.g., from stealing), independence from parents, and sexual opportunities. Moffitt (1993) suggested that adolescence-limited individuals desist from crime once this “maturity gap” closes, and they can achieve status through prosocial means, such as employment, moving out of the family home, and beginning sexual relationships in later adolescence. Only those who become trapped by the consequences of their criminal behavior—missed education, time in custody, lack of employment opportunities because of a criminal record, ostracism—might persist into adulthood for lack of better, prosocial options.

Predictions about the trajectories of these two groups have been supported by subsequent longitudinal follow-up research (e.g., Moffitt, Caspi, Harrington, & Milne, 2002), although some investigators have suggested that other trajectories exist, including a group that is persistent from childhood into adulthood but that then desists and a group that has a late and unexpected adult onset to criminal behavior (e.g., Laub & Sampson, 2003). Quinsey et al. (2004) suggested the possibility of two distinct life-course-persistent trajectories, the first as described by Moffitt (1993) and a second that does not show the same pattern of neuropsychological difficulties but instead shows a life history of persistent antisocial and criminal behavior as a result of psychopathy (Lalumière, Harris, & Rice, 2001). These two life-course-persistent trajectories may have different causes (Quinsey, 2002; Quinsey et al., 2004).

Applying this developmental trajectories perspective to sexual offending against children, life-course-persistent sex offenders are expected to be a small minority who account for a disproportionate number of sexual offenses. Life-course-persistent offenders would be more likely to nonsexually or sexually reoffend than the adolescence-limited sex offenders, who primarily offend because they temporarily lack other options. Linking this perspective back to the motivation–facilitation model, antisocial trajectories explain the relative strength of facilitation factors and can accommodate intense mating effort because intense mating effort is positively associated with antisociality (Lalumière & Quinsey, 1996; Lalumière et al., 2005).

This perspective does not explain paraphilic motivations. Some of the life-course-persistent and adolescence-limited offenders have pedophilia or hebephilia and thus are more motivated to seek out child pornography and sexual contacts with children. G. T. Harris, Rice, Hilton, Lalumière, and Quinsey (2007) suggested that, among the life-course-persistent offenders, psychopathic offenders will be less likely to be pedophilic than nonpsychopathic offenders, as it is the latter who are more likely to have the neuropsychological vulnerabilities that might be associated with the etiology of pedophilia. Psychopathic offenders will be more likely to seek out girls who are peri- and postpubescent, whereas nonpsychopathic offenders would be expected to be more likely to target younger children and boys. Life-course-persistent offenders who also have pedophilia or hebephilia are expected to be the highest risk group (see

Chapter 7

).

A developmental trajectories perspective is also compatible with other models described in this chapter. Antisociality is represented in Finkelhor’s (1984) disinhibition, W. L. Marshall and Barbaree’s (1990) self-regulation problems, G. C. N. Hall and Hirschman’s (1992) personality problems, and Ward and Siegert’s (2002) emotional regulation problems. Thus, sex-offender-specific explanations can be linked back to what researchers know about the onset and persistence of crime in general. Some unique factors still need to themselves be examined and, if they are indeed distinctive, they need to be explained. Here, I focus on those factors that cannot be subsumed under atypical sexual interests, antisociality, interpersonal deficits, or their combinations. For example, early exposure to sex or pornography might be associated with atypical sexual interests; offense-supportive attitudes and beliefs about children might reflect both atypical sexual interests and antisociality; empathy deficits may reflect antisociality; and emotional identification with children might reflect both atypical sexual interests and interpersonal deficits.

Factors are considered unique to the extent they distinguish sex offenders against children from other men. To illustrate this logic, all the theories reviewed earlier in this chapter would predict that male sex offenders, as a group, would differ on measures of pedophilia when compared with other sex offenders, non–sex offenders, or nonoffending men (see

Chapters 1

and

2

). Given that pedophilia is clearly very salient and the most distinctive factor regarding sexual offending against children, I devote the

next chapter

to discussing its etiology. I do not discuss antisociality on its own, because it distinguishes sex offenders against children but in an unexpected direction: Sex offenders against children score lower on measures of antisociality than other sex offenders or other offenders, although they are still more antisocial than their nonoffending counterparts. Although antisociality does appear in sex offenders against children and predicts sexual recidivism, it is not unique in the sense that its presence is distinctive. Later in this chapter, I provide a brief overview of emotional congruence with children as a factor that is likely related to pedophilia, supported by a recent meta-analysis clarifying the role this psychological construct plays. I also give special attention to childhood sexual abuse as a unique factor given the clinical and public interest in the notion of an abused–abuser link.

Some of the evidence I present next is from a meta-analysis of studies that compared adolescents who had sexually versus nonsexually offended (Seto & Lalumière, 2005, 2010). I also review studies that have compared adult sex offenders and other offenders. Where available, I review longitudinal data relevant to the onset of sexual offending against children.

PEDOPHILIA

One intuits that people will orient their sexual behavior toward persons they are sexually interested in: Straight men are oriented toward women, gay men are oriented toward other men, and pedophilic men are oriented toward children. This is an empirically supported association; as described in

Chapter 2

, men who sexually offend against children can be distinguished from other men on measures of their self-reported sexual interests, sexual arousal to children, and sexual behavior involving children (including child pornography viewing). Both adolescent and adult sex offenders with histories of sexual contacts with multiple children, younger children, and boys show greater sexual arousal to stimuli depicting children (Seto & Lalumière, 2001; Seto et al., 2003; Seto, Stephens, Lalumière, & Cantor, 2017). Last, as I discuss in more detail in

Chapter 7

, measures of pedophilia predict new sexual offenses among identified sex offenders (Hanson & Morton-Bourgon, 2004, 2005). Again, this does not imply that all persons with pedophilia have had, or will seek, sexual behavior with children, but this strong association cannot be ignored.

HYPERSEXUALITY

Hypersexuality is relevant to sexual offending; for example, measures of hypersexuality are higher in sex offender samples than in comparison groups (e.g., Knight & Sims-Knight, 2003), and excessive sexual preoccupation predicts sexual recidivism among identified sex offenders (Hanson & Morton-Bourgon, 2005; Kingston & Bradford, 2013; Lussier, Leclerc, Cale, & Proulx, 2007). However, it is less clear what role hypersexuality plays in sexual offending against children specifically; an exception is Kingston and Bradford (2013), who had a sample mostly composed of offenders against children (500 of 586 cases).

MATING EFFORT

Evidence from community samples indicates that intense mating effort—as reflected in number of sexual partners and a greater interest in partner novelty and variety—is relevant to sexual offending against peers or adults (Abbey, McAuslan, & Ross, 1998; Malamuth, Linz, Heavey, Barnes, & Acker, 1995). However, few studies have compared sex offenders against children to other groups in their noncriminal sexual histories or conventional sexual experiences, and some of these indicators are related to hypersexuality as well as mating effort. In their pioneering Kinsey Institute study, Gebhard, Gagnon, Pomeroy, and Christenson (1965) found that sex offenders against children were less conventionally experienced sexually than sex offenders against adults. Cortoni and Marshall (2001) compared 30 sex offenders against children and 29 sex offenders against adults: Those who victimized children reported a significantly later onset of first genital intercourse, but they did not significantly differ in the age of their first sexual partner, average number of sexual partners, or variety of sexual activities they had engaged in. The two groups also did not significantly differ in their self-reported use of pornography or frequency of masturbation. One possible explanation here is that sex offenders against children score higher on these indicators than nonoffending men but score lower than sex offenders against adults.

PSYCHOSEXUAL DEVELOPMENT

Separate from explanations focusing on paraphilias, hypersexuality or intense mating effort, some theorists have suggested that male sex offenders differ from other men in their psychosexual development, which could include childhood sexual abuse, early exposure to sex or pornography, and exposure to sexual violence (e.g., witnessing sexual abuse perpetrated by older sibling or parent; Beauregard, Lussier, & Proulx, 2004). Depending on individual differences and initial conditions, these disruptions in psychosexual development could increase the likelihood of paraphilic or hypersexual behavior and/or decrease the likelihood of conventional sexuality, such as age of onset of masturbation, onset of conventional sexual activities, or number of sexual partners.

CHILDHOOD SEXUAL ABUSE

One of the most frequently discussed unique explanations of sexual offending against children is the

abused–abuser hypothesis

, sometimes referred to as the

abuse cycle

or

intergenerational transmission of sexual abuse

(Johnson & Knight, 2000; Kobayashi, Sales, Becker, Figueredo, & Kaplan, 1995). The abused–abuser hypothesis suggests that boys who have been sexually abused are relatively more likely to sexually offend later in life, whether as an immediate reaction to the sexual abuse or because of a perturbed development resulting in poor attachment, social skills deficits, and maladaptive coping.

The logic underlying the hypothesis is that something about experiencing childhood sexual abuse increases the risk of sexually offending later in life. Both Ryan, Lane, Davis, and Isaac (1987) and W. L. Marshall and Marshall (2000) suggested that some young people will use sex as a way of coping with negative feelings about sexual abuse and thus may be more likely to be coercive to obtain sex or may condition themselves to respond sexually to children through fantasy and masturbation. Burton (2003) suggested several social learning mechanisms, for example, that some abused youth might model the perpetrator in an effort to regain a sense of control and mastery; some might condition themselves to respond to children through fantasy and masturbation; and some might have different cognitions about the acceptability of adult–child sex because of cognitive dissonance or other effects.

Seto and Lalumière (2010) found evidence that sexual abuse history is linked to sexual offending: Adolescent sex offenders scored higher on sexual abuse history, early exposure to sex or pornography, and exposure to sexual violence than other adolescent offenders. Adult sex offenders are also more likely to have sexual abuse histories than other adult offenders, with the effect being stronger among those who have offended against children in a meta-analysis by Jespersen, Lalumière, and Seto (2009). In their systematic review, Whitaker et al. (2008) found a similar result comparing sex offenders to other offenders, and also showed the same group difference comparing sex offenders to nonoffending men in 11 studies. The difference in sexual abuse history was much larger than for physical abuse history in both adolescent and adult offender comparisons (Jespersen et al., 2009; Seto & Lalumière, 2010). Most of the cross-sectional research has relied on clinical or criminal samples; however, Fromuth, Burkhart, and Jones (1991) found no association between sexual abuse history and admitting to sexual contact with a child in a community sample of male students.

Childhood sexual abuse may be a risk factor for the onset of sexual offending, but it is neither necessary nor sufficient. The evidence is complicated because cross-sectional studies find adolescent and adult sex offenders are much more likely to have sexual abuse histories than other adolescent or adult offenders, respectively (Jespersen et al., 2009; Seto & Lalumière, 2010). On the other hand, longitudinal studies of abused children do not always find a significant association between sexual abuse history and later sexual offending. Salter et al. (2003) followed 224 sexually abused boys (mean age of 11) for 7 to 19 years and found that 26 of them (12%) subsequently committed a sexual offense, mostly involving a child. These sexual offenses typically occurred within a few years after the sexual abuse occurred, and most of the boys (19 of 26) committed a single sexual offense during the follow-up. Those who committed sexual offenses were also more likely to commit nonsexual offenses as well. Sexual offending was associated with physical neglect, lack of supervision, and sexual abuse by a female perpetrator.

Widom and Massey (2015) looked at the abuse association prospectively in a large sample of 908 children who had substantiated claims of physical or sexual abuse or neglect, followed to adulthood (average age of 51) along with 667 comparison children matched for age, sex, ethnicity and approximate social class. Physical abuse significantly predicted later sexual offending, whereas sexual abuse was not significant, although it had a comparable magnitude of association. Even if both were statistically significant, Widom and Massey’s finding suggests the association is not necessarily something specific about sexual abuse and sexual offending. Last, sexual abuse is not a significant predictor of sexual recidivism, suggesting sexual abuse might play a role in the onset of offending, but not its persistence (Hanson & Morton-Bourgon, 2004, 2005).

In a large sample of Finnish twins, Forsman, Johansson, Santtila, Sandnabba, and Långström (2015) examined the association of childhood maltreatment and sexually coercive behavior and found a significant relationship, even after controlling for familial confounds through the twin design, which supports a causal interpretation. The results suggested a nonspecific association for sexual abuse: Sexual abuse had an adjusted odds ratio of 2.85, compared with 2.11 for physical abuse, 2.53 for emotional abuse, 1.98 for physical neglect, and 1.66 for emotional neglect. The adjusted odds ratio for any form of maltreatment being associated with sexually coercive behavior was 2.31.

EARLY EXPOSURE TO SEX OR PORNOGRAPHY

Seto and Lalumière (2010) also found meta-analytic evidence that adolescent sex offenders differ from other adolescent offenders in having more early exposure to sex or pornography (eight studies) or exposure to sexual violence within the family (four studies). Again, consistent with the idea that something specific about psychosexual development that is linked to becoming a sex offender, neither exposure to nonsexual violence within the family (eight studies) nor outside the family (five studies) distinguished adolescent sex offenders. Adolescent offender groups showed no differences in conventional sexuality indicators, such as age of onset of intercourse or number of sexual partners (nine studies; Seto & Lalumière, 2010).

The evidence is more mixed for adult sex offenders. On the one hand, different researchers have demonstrated that indicators such as number of sexual partners and age at the time of first intercourse are positively correlated with sexually offending against peers in community samples (Knight & Sims-Knight, 2003; Lalumière, Chalmers, Quinsey, & Seto, 1996). On the other hand, other studies have not shown this difference; for example, Cortoni and Marshall (2001) did not find any significant differences between 59 sex offenders and 30 nonsexually violent offenders in age of onset of first intercourse, number of sexual partners, or use of pornography. Gebhard et al. (1965) found that both sex offenders and other offenders had more extensive sexual experiences than nonoffending men, but sex offenders had less sexual experience than other offenders. Part of the confusion may be a result of the questions that were asked; if only questions about adult sex and pornography were asked, then one would expect sex offenders against children to score lower than sex offenders against adults.

EMOTIONAL CONGRUENCE WITH CHILDREN

McPhail, Hermann, and Nunes (2013) defined

emotional congruence with children

as an exaggerated affective and cognitive affiliation with children and the concept of childhood. This affiliation is reflected in particular attitudes and beliefs about children, a feeling of having more in common with children than with adults, and a preference for intimate relationships and nonsexual contact with children. In their meta-analysis of 30 studies examining emotional congruence with children, McPhail et al. found that extrafamilial offenders against children scored significantly higher on emotional congruence than other groups of men (the most common comparison was with sex offenders against adults, 10 studies), whereas intrafamilial offenders against children scored lower than the extrafamilial offenders and many of the comparison groups (15 studies). Moreover, emotional congruence with children predicted sexual recidivism among extrafamilial offenders (five studies) but not among intrafamilial offenders (three studies), and only extrafamilial offenders showed significant pre–post decreases in emotional congruence because of participation in treatment (five and three studies, respectively). As noted by the authors, some of these findings were based on a small number of studies.

McPhail et al. (2013) offered an interesting explanation for the group differences in emotional congruence with children and the prediction of recidivism: Perhaps high emotional congruence with children increases risk of offending against unrelated children because it increases proximity to children, and in conjunction with pedophilia or antisociality, it increases the likelihood of sexual offending. In contrast, lower emotional congruence may facilitate sexual offending against related children because it provides emotional distance from potential victims who are already known and connected to the adult. Low emotional congruence in the intrafamilial context may also reflect a lack of involvement with the related child, which again may reduce inhibitions against sexually offending against a relative (see

Chapter 6

).

McPhail, Hermann, and Fernandez (2014) tested explanations for emotional congruence with children by examining its correlates in victim characteristics, offending, and psychologically meaningful risk factors, using a sample of 229 convicted sex offenders with child victims. These explanations included the blockage component of Finkelhor’s (1984) model, in which someone might be less able to build meaningful relationships with adults as a result of poor social skills, social anxiety, or other factors; a “sexual deviance” model, in which emotional congruence of children is closely linked to pedophilia and to offense-supportive cognitions about children and sex; and an immaturity model, in which individuals who are high in emotional congruence with children are more likely to be young, lower in IQ, and/or emotionally immature. The results were seen as most supportive of the sexual deviance model, because emotional congruence was positively correlated with pedophilia, offense-supportive cognitions about children, and sexual self-regulation problems.

INTERPERSONAL DEFICITS

In our (Seto & Lalumière, 2010) meta-analysis, we found adolescent sex offenders did not differ from other adolescent offenders on measures of social skills deficits. In contrast, Dreznick (2003) reviewed 14 studies—all but one involving adult male offenders—and found that sex offenders scored significantly lower on both self-report and performance measures (e.g., role-play) of social skills than other offenders. Since the Dreznick meta-analysis, Abracen et al. (2004) compared 166 adult sex offenders with adult victims, 168 sex offenders with unrelated child victims, and 177 sex offenders with related child victims on measures of social skills deficits. Both groups of men who had sexually offended against children had more social skills deficits than the offenders against adults. In addition, offenders against unrelated children, who would be more likely to be pedophilic, scored higher on social skills deficits than offenders with only related child victims.

It is possible that sex offenders against children may show social skills deficits in their interactions with adolescents or adults but may not show such deficits in their interactions with younger children. In other words, men who are socially awkward with other adults may not show the same problems when interacting with children or may even be more skilful because they are more comfortable with children than other adults. Moreover, sex offenders against children may show no deficits in their social connections with other sex offenders against children, possibly because they do not have to be as secretive as they might be with other adults because of the stigma associated with sexual offending against children (Hanson & Scott, 1996; Jahnke, Imhoff, & Hoyer, 2015; Jenkins, 1998). More research using self-report and observational measures of social skills with both adults and children is needed to examine these questions.

OTHER SEXUALLY OFFENDING POPULATIONS

I repeat here that a large gap in theoretical and empirical work is the extent to which models developed to explain adult male contact sexual offending generalize to other parts of the population, including female offenders, adolescent offenders, and individuals committing noncontact sexual offenses such as exhibitionism and voyeurism.

Female Sex Offenders

A big question for the field is the extent to which female sex offenders are similar to or different from male sex offenders (i.e., excluding noncontact offenses and sexual assaults of adults because these are rare in the female population; see Gannon & Cortoni, 2010). D. Harris (2010) explored why some gender differences are to be expected in the factors that are important in explaining sexual offending, such as gender roles and the role of coercion by male accomplices in some cases.

Some researchers have examined female sexual offending through a feminist lens (see, e.g., Rousseau & Cortoni, 2010). Researchers in the past have incorrectly assumed that most women who were sexual offenders committed their offenses in conjunction with men who led the offending; that is, that the women were passive, and possibly manipulated or abused themselves. Another explanation was that women sexually offended because of their serious psychopathology, which might include their own histories of trauma, personality disorder, or family turmoil. Although women who have sexually offended tend to score high in psychopathology measures, it is not clear that this psychopathology is causal; the psychopathology may be a consequence of sexually offending or being identified. Also, as Rousseau and Cortoni (2010) pointed out, diagnosis itself can be gendered because of the common bias to explain female sexual offending as due to psychopathology.

Considering again the criminological literature, one can see similarities and differences between female and male offenders more generally: (a) Crime has a big gender gap, especially in violent crime and in sexual crime; (b) women are less likely to be in a life-course-persistent trajectory than men (Fergusson & Horwood, 2002); (c) many of the risk factors are similar in both populations, with factors such as offender age, criminal history, antisocial personality, and substance use are related to the likelihood of further crime (Smith, Cullen, & Latessa, 2009); and (d) women are much less likely to sexually reoffend than male offenders, but they are similar in risk factors for recidivism (Freeman & Sandler, 2008; Sandler & Freeman, 2009).

Adolescents Who Have Sexually Offended

Adolescents who have sexually offended differ from other adolescent offenders in a number of ways that are also found among adult offenders (Seto & Lalumière, 2010). Similar to adult offenders, adolescents who have sexually offended are more likely to differ in their psychosexual development by being more likely to have sexual abuse, to be exposed to sex or violence, and to have fewer conventional sexual experiences. They are more likely to report or show evidence of atypical sexual interests or behavior but are less likely to have extensive nonsexual criminal histories.

Noncontact Offenders

Although noncontact offenders account for many sexual offenses, theories are much less developed about these forms of sexual crime. Paraphilic motivations are prominent in these cases, sometimes to the extent that almost all noncontact offending is viewed as motivated by paraphilias: Exhibitionism and indecent exposure; voyeurism and invasion-of-privacy offenses, such as surreptitious recording or observation of people undressing or engaging in sexual activity; pedophilia and child pornography offending. In line with self-control theory of crime and the motivation–facilitation model of sexual offending, the presumption is that those who do not have sufficient self-control over concomitant paraphilias will commit sexual offenses.

WEIRD

Finally, as is true for so much social science research, almost everything that is known about sexual offending comes from so-called WEIRD (Western, educated, industrialized, rich, democratic) samples (Henrich, Heine, & Norenzayan, 2010). Researchers need to conduct cross-cultural and more diverse research to better understanding sexual offending against children and pedophilia outside of the WEIRD context. This work is only just beginning to emerge; the available evidence suggests similar factors are often at play in explanations of sexual offending, but culture plays a role too (Smallbone & Rallings, 2013; Zeng, Chu, Koh, & Teoh, 2015). Nagayama Hall, Teten, DeGarmo, Sue, and Stephens (2005) compared Asian and European Americans and found similarities in their risk factors for sexual aggression against women in terms of what Malamuth (2003) described as hostile masculinity and impersonal sex, but differed in the protective influence of loss of face. Face is a salient aspect of many Asian cultures, in which the loss of the respect of others is seen as highly negative, both for oneself and for one’s family. Concern about loss of face for self and for family would be expected to increase inhibitions against sexually offending. One might also expect cultural differences in expressions of sexuality more generally and in expectations of self-control. Evidence that the relevance of loss of face is cultural rather than related to perceived or actual minority status is that Nagayama Hall et al. (2005) found no difference between mainland Asian Americans and Asian Americans who were living in Hawaii, where they are the population majority. Whether culture plays a role in explaining sexual offending against children remains to be explored.

Relatedly, Leguízamo, Lee, Jeglic, and Calkins (2017) recently found that the Static-99R, a commonly used sex offender risk assessment tool (see

Chapter 7

, this volume) predicted sexual recidivism among Latino offenders born in the United States or Puerto Rico but not among Latino offenders born elsewhere, suggesting culture of origin may play a role in the relative importance of factors to explain sexual offending. More research is needed, even though this work is difficult because researchers may have an incomplete picture of criminal history for immigrants coming from countries with less systematic records and international reporting of criminal histories, and they may miss some recidivism because of some offenders being deported following their conviction for sexual offenses.

CHAPTER SUMMARY

Evidence supports both generalist and specialist theories of sexual offending against children, inasmuch as factors that are important in general theories of crime—such as antisocial personality traits, offense-supportive attitudes and beliefs, substance use, and opportunity—are also involved in contemporary explanations. Discoveries in developmental criminology are directly relevant. Many offenders against children have also committed nonsexual offenses, and the likelihood of nonsexual recidivism is higher than sexual recidivism. Nonetheless, evidence indicates that some distinctive factors are consistent with specialist theories, especially pedophilia, but so too are other sexual motivations, such as excessive sexual preoccupation and intense mating effort.

This hybridization of generalist and specialist explanations is explicitly recognized in the motivation–facilitation model, which encompasses distinctive sexual motivations for sexually offending against children, as well as facilitation factors associated with general crime as well. Other explanations of sexual offending reviewed in this chapter also recognize a role for sexual interest in children and also recognize that it is neither necessary nor sufficient, because other factors also come into play. Each of these models has its strengths and weaknesses; the theoretical understanding of sexual offending will grow as models are put to the test, both on their own and against other models. More research is clearly needed, because most of this evidence comes from research on persistence of sexual offending, rather than its onset. Moreover, most of the research reviewed in this chapter comes from research on identified adult male contact offenders in WEIRD societies; it is less clear whether these models are valid for women who sexually offend, adolescents who sexually offend, those who have committed noncontact sexual offenses, and those outside of WEIRD societies.