A flock with a variety of breeds is beautiful and practical.

Knowing full well the popularity of chicken keeping in Portland, we were startled to read a 2013 US Department of Agriculture survey that conservatively estimated that more than 600,000 nonfarm American homes hosted flocks of chickens in urban and suburban contexts. The survey also revealed that although less than 1 percent of households had chickens at the time, about 4 percent of folks without chickens planned to start raising them within the next five years. That’s a lot of new chicken keepers, and a lot of chickens!

Nearly 20 billion chickens inhabit our planet, making them the most populous livestock by a factor of ten over their nearest competition, cattle. The majority of these birds are raised for meat, and about 75 percent of those are produced using “intensive” methods, a euphemism for “factory farmed.”

It’s sobering to consider that this agricultural juggernaut, so vital to our global food supply, relies heavily on a very shallow gene pool consisting almost exclusively of a single type of chicken, the Cornish Cross. This hybrid merges a short, but thickly muscled, British breed with a longer-boned, more upright Asian type for the singular purpose of efficiently converting cheap feed sources to meat. Within massive, environmentally controlled buildings, these birds park themselves at a feeding station, start eating, and don’t stop until they are ready for market (or succumb to maladies caused by their rapid growth), going from egg to grocery store in less than two months.

The welfare and genetic-diversity issues are similar in the egg industry. In the United States, in the month of October 2016, 300 million individual hens cranked out a record 7.51 billion eggs. The vast majority of these birds are variants of a single breed, the Leghorn, a heavy layer of white eggs that originated in the Mediterranean region.

As intensive agriculture has advanced globally, many traditional, locally adapted landrace breeds (domesticated breeds that have developed distinct features over time in response to their environment and by being isolated from other populations of the same species, rather than through formal breeding) have been abandoned in favor of modern breeds tailored for close confinement and intensive feeding. When these landrace breeds vanish, with them go the genes that contain the many unique traits for which they were selected, along with untold millions of others with additional attributes that will be increasingly valued in a future marked by climactic shifts and resource scarcity. The loss is also cultural in the sense that each breed is a reflection of the values, environmental settings, and even aesthetic tastes of the humans who developed it.

In a typical factory farm, crowding chickens with low breed diversity in high-density conditions and a highly artificial environment practically invites health problems.

Modern breeding and agricultural systems are displacing traditional chicken farmers, who depend on regionally adapted and diverse flocks.

In a hopeful sign, a few major producers of commercial chicken breeds are beginning to reverse the trend of genetic simplification by incorporating more genetic diversity and developing breeds for alternative farming systems such as pasturing. Hy-Line International, an old-school heavyweight breeder and hatchery of Leghorn hybrids, now offers a range of breeds that produce white, brown, or tinted eggs and are better equipped for living longer and thriving in more humane and sustainable alternative production systems.

Although we applaud these modest advances by the big guys, it’s clearer than ever to us that the remaining dual-purpose generalists (breeds that provide both meat and eggs) and other unique, regional, and odd breeds are the sacred inheritance of the backyard and small-flock chicken keeper. Our support of these breeds is their greatest hope for survival. This need not mean, however, that we must limit ourselves exclusively to keeping so-called heritage breeds, because they can also be combined and recombined as new breeds to improve vitality and increase diversity.

Of the more than 400 breeds of chickens that inhabit the world, only a small fraction is available through domestic breeders and hatcheries in the United States. By some estimates, only about 70 chicken breeds (plus color variants) have been established here during the 500-year importation history of poultry in North America, and most of those are slowly vanishing, displaced by a tidal wave of modern hybrids bred specifically to live in intensive commercial farming systems.

Our store sources chicks from several hatcheries that offer reasonable breeding quality at prices that our customers are willing to pay. Feed stores typically offer this quality level or lower—an important factor to consider when seeking birds to establish or expand your own flock. Although average-quality hens can make serviceable pets and layers, skillful breeding reveals the best features of a breed, making hens more likely to be terrific layers, tame pets, or a good fit for whatever traits have drawn you to them. Recent research has revealed that, beyond aesthetic and productivity considerations, disease resistance and even life expectancy are heritable and will be heavily influenced by the quality and diversity of the breeding, nutrition, and the conditions in which parent hens are kept. Happily, these factors favor reputable breeders who take the time to develop good bloodlines.

At a minimum, we recommend that you inquire about the particular hatchery that supplies chicks if you purchase them from a feed store (and ask about vaccines while you’re at it). Do a little research on the hatchery. How many breeds do they offer? Where are they located? Do they keep their own breeding stock—and, if not, what can they tell you about the farms that supply them with hatching eggs?

Chicks of truly rare breeds (or high-quality lines of more common breeds) regularly exceed U.S. $200 each, with some individuals of exceptional quality fetching prices in the five figures. Although it’s not necessary, or even advisable, for beginners to spend this much, we encourage veteran chicken keepers to experience for themselves the true potential of well-bred chickens and to support small breeders’ efforts to maintain their breeds and preserve unique poultry genetics for future generations.

If you do opt for chicks of higher quality or rare breeds from craft producers, be aware that these will be available only unsexed, as straight-run, meaning that you’re likely to get both males and females. Have a plan ready in advance for what to do with the males if they are not allowed in your area.

From the easy-to-appreciate, fluffy, blond Buff Orpington, to the slightly bizarre, stilt-legged Malay and buzzard-like Naked Neck, we find something to appreciate about all chicken breeds. Our favorites for backyard chicken keeping are known for their utility, appearance, temperament, novelty, or a combination of those traits.

Much has been written about commonly available breeds, so we don’t devote much space to those here, other than naming our top picks. Instead, we decided it would be much more interesting, not to mention critically important for preservation, to highlight a few unusual and endangered breeds that are well suited for small flocks and that deserve more attention.

With so many interesting breeds, we found it difficult to limit ourselves. If we had more pages and time, we could wax poetic about the intricate patterns of the Laced Wyandotte (including the ultra-rare Blue Laced Red colorway!), the handsome and intrepid Brahma that was bred to thrive in the demanding environment of the Himalayas, and fine Mediterranean examples such as the prolific white-egg-laying, large-bodied Catalana hen from Spain that rarely gets broody and is very tolerant of heat. To conserve space, our description of each breed’s main attributes is brief. Let careful consideration of your own unique location and needs guide your choice of breeds.

Though each breed has at least one particular standout trait, we nominate the Plymouth Rock and Ameraucana as all-stars that can do it all—from laying eggs and turning compost to surviving the rough handling of a toddler. We’ve always recommended that new chicken keepers start with some common breeds like these and move on to more exotic options after they have a little more experience. That said, if you must have a rare and beautiful specimen like a Lavender Orpington or Blue Laced Red Wyandotte and you find one for sale, by all means, nab it!

Outstanding backyard hen

• 6 to 8 pounds

• Attractive, commonly available, and genetically robust

• Early and highly productive layer of large, light brown eggs

• Potential year-round layer given suitable conditions

• Quick to mature with early graduation to coop

• Easily tamed and adaptable to family life

• Excellent forager and garden helper

• Hardy in hot and cold, robust, and long-lived

• Somewhat vanilla personalities

• Hearty appetites must be balanced by activity to avoid obesity

Rocks, as they are usually known, are a relatively old American breed that was likely derived from a series of crosses between the similar French Dominique and one or more Asian breeds (possibly Java, Dark Cochin, or Brahma) in the mid-1800s. Their broad genetic base has proven highly advantageous, enabling breeders and hatcheries to preserve much of their utility and vigor to the present day. Only two colors are commonly available—barred (stripes of black and white, almost checkered) and white—but several more color variants persist and are worth seeking out. Generally speaking, the barred strain is favored as a dual-purpose breed, and the white is raised primarily for meat (though they are also good layers), as is often the case with white breeds, because of the cleaner-looking carcass produced after plucking. Rocks were crossed with Cornish chickens to create modern meat hybrids.

Before World War II, hatcheries produced specialty strains of this breed that were collectively the most common egg layers and meat-producing chickens on U.S. farms. Perhaps this was because of their very early age of first lay and quick rate of growth. When they are fed sufficient protein, you can expect to see their first pale brown eggs a staggering three to four weeks before most other breeds. Early physical maturation makes possible an early and welcome exit from the brooder to the coop, typically a week sooner than other dual-purpose breeds and up to two weeks earlier than smaller-bodied, white-egg-laying breeds. As a meat bird, they are considered to be early finishers for a heritage breed, but not when compared to modern hybrids.

These truly hardy birds usually take cold weather in stride, often managing to lay straight through moderate winters (if not molting). Remarkably, we’ve observed that they also tolerate heat fairly well if given shade, water, and moist earth. This versatility earns them a top position among other breeds for ease of care. We also marvel at their ability to thrive in urban confinement and on free-range farms; along with the Rhode Island, Rocks are a common sight in both environments. They love to dig and scratch, making them ideal members of hard-working flocks in mobile coops and pens.

Despite their work ethic, their personality is fairly calm, they are easy to hold and stroke, and they can be readily tamed as pets. Their large bodies also ground any aspirations of flight and slow their walk, so they are more likely to stay where you put them and are easy to catch when they don’t. Barred Rocks are known to get along well with other hens and other well-behaved pets, and they are always a favorite of children, perhaps because of their resemblance to zebras.

Barred Rocks are an ideal component of a mixed flock, with plumage that’s visually complementary with that of other breeds. Their eggs possess both a distinct color (pale brown, almost pink) and shape (slightly pointy) that enables easy differentiation in the nest.

Barred Rock chicks are semi-autosexing, which means they can be sexed with fair accuracy. The mostly black fuzz on a young female is marked by a faint white dot on her head. This becomes less distinct over time, but males may be identified by more white on their wing tips and a generally lighter appearance.

The only commonly available breed that rivals Rocks for our affection

• 4 to 5 pounds

• Blue-tinted eggs are unique and appealing

• Prolific year-round layer in most climates

• Relatively hardy and disease resistant with few congenital problems

• Genetically robust

• Good temperament with potential to tame as a pet

• Newfound popularity may lead to careless breeding in the near future, undermining genetic quality

• May be difficult to find a specimen of the true breed (hybrid Easter Eggers are common and passed off as Ameraucanas)

• Not meaty enough to be truly dual-purpose

• Better flyer than larger breeds; may need wing feathers trimmed

Ameraucanas are easily confused with Easter Eggers and are sometimes sold by this name, but, technically, Ameraucanas are true-breeding layers of eggs in a range of blues, while Easter Eggers are similar-looking hybrids that lay slightly more green-blue-tinted eggs. Adding to the confusion, the Ameraucana Breeders Club is confident that the Ameraucana is not simply an improved version of the rumpless (without a tailbone and often without tail feathers), similarly blue-egg-laying Araucana from South America, but is in fact an entirely separate breed that was standardized in North America in the late 1970s. It now seems likely that most of the birds sold as Ameracauna or Araucana are neither, and are indeed some sort of hybrid Easter Egger. For the purposes of most home chicken keepers, they are essentially the same bird, although we would select a properly labeled Ameraucana over an Easter Egger any day, and twice on Sunday.

Our Ameraucanas are, without fail, our best layers each year, and customers and friends usually report similar results, which is somewhat surprising, considering most were purchased for a bit of egg color novelty. This exceptional laying ability is probably in part a result of being a recently developed and skillfully bred line, meaning that the breed has not gradually lost vigor over many generations of line breeding with limited stock, like some of the heritage breeds. Some males may achieve admirable size, but Ameraucanas are not considered top-quality meat producers. Though they are not quite as hardy as some of the big European chickens, we’ve observed Ameraucana to be exceptionally healthy and long-lived in our temperate backyard setting.

If you have a heavy breed hen, you may not need to clip her wings, or you might just clip one to make flights more awkward and embarrass your hen into staying put. For the rest of the breeds, such as Ameraucanas, you will likely need to trim some flight feathers to keep them in unroofed runs or in your yard while they forage.

Our definition of a heavy breed is any large bird that you can actually catch. It usually lays brown eggs. If you can’t catch it, and particularly if it lays white eggs, it’s probably not a heavy breed. If it flies over the fence and is never seen again, just shake your head and mutter knowingly, “Those darn flighty Mediterranean breeds. Should have clipped both wings,” as you gaze in the direction that you imagine it flew.

Wing clipping is a simple process if you have a helper, a good pair of sharp scissors, and a couple of headlamps. Start out at night, while the hens are sleeping; they will remain in a torpor and are much easier to handle in the dark. After your partner plucks a hen from her roost and gently (but firmly) holds her with wings tucked against her body, take hold of a wing. Extend it to reveal the five or six longest feathers that look like they would make good quill pens for writing. Looking from the feather tips toward where they attach at the meaty part of the wing, locate where the shaft thickens and usually changes color. Do not cut below this area. Using sharp, full-sized scissors, cut off all of these feathers about halfway down from the tips, so they are roughly even with the remaining small feathers on this side. There should be no blood, but if there is, stop and reposition the cut a bit further out from the main wing (use styptic powder for the rare times bleeding does not stop almost immediately on its own). Repeat on the other wing for increased effectiveness.

The iconic chicken of the backyard and homestead

• Prolific layer of large brown eggs

• Few health problems and a strong constitution, even as a chick

• Terrific forager and efficient consumer of feed

• Infrequently broody

• Adaptable to confinement or free ranging

• Can be a bit high strung, but with a little extra attention, she’ll be your best garden buddy

• Males raised for meat mature in 14 to 18 weeks, up to 8 pounds

This famous American heritage breed actually does hail from Rhode Island, where it can trace its ancestry to a single black-breasted red Malay cock that is now preserved for posterity in the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC. Appropriate for an American breed, this chicken’s pedigree is a motley blend of immigrant breeds from East and West, with Java, Shanghai (now known as the Brahma), and the prolific Brown Leghorn from the Mediterranean rounding out the mix. Rhode Island Red roosters contribute the paternal genes for various types of sexlink hybrids, so called because males and females can be distinguished at hatch by their feather color or markings.

The deep mahogany plumage characteristic of the breed is not the only color available. There’s a treasure trove of genetic potential and vigor embodied by the lesser-known Rhode Island White. Produced by making a fresh but similar mix of Asian and Mediterranean breeds around 1900, the white chickens are reputed to surpass the reds in laying and meat production. This breed was identified by The Livestock Conservancy as being threatened, with less than 3000 birds counted in their 2015 poultry census. The original and darker Rhode Island Reds are becoming rare as the breed is “improved” to meet industry needs.

Consistent layers of large, dark brown eggs

Barnevelder plumage is gorgeous, and their deep brown eggs nearly match their feathers in color intensity.

• Prolific producer of up to 200 eggs per year

• Steady temperament, docile, and easily handled—great candidate for taming as pet if handled often while young

• Well adapted to confinement or free range

• Fairly cold hardy

• Good forager

• Slow to mature

• Males raised for meat mature in 20 weeks to 8 pounds

This large, 200-year-old Dutch breed is still admired for her dark chocolate-brown eggs and intricate feather patterns. The breed is a sound dual-purpose (meat and egg) chicken with its robust blend of European and Asian genetics. Roosters are particularly handsome with plenty of meat on them, though their full weight of nearly 8 pounds is not reached until the relatively old age of 20 weeks.

A True British Classic

• Excellent layer of cream-to-tan-colored eggs

• Friendly and easily tamed as pet

• Great forager

• Adaptable to confinement or free range

• Very cold hardy

• Sensitive to extreme heat and humidity

• Males are meaty, at 6 to 8 pounds

Sussex checks all the boxes—a hardy, attractive, heritage breed that is notable for meat and egg production. Originating in the cool North Atlantic region, the breed can be sensitive to very hot, humid weather, and for this reason the Sussex is not recommended for the U.S. Deep South or subtropical areas. They are unusual as a surviving pure landrace U.K. breed—they lack Asian genes common in other breeds.

The gorgeous speckled brown feather pattern is most common in the United States, but several breeders now offer the more unusual color variants such as the Light Sussex. We encourage you to support breeders’ efforts by selecting these variants if you see them. This endangered heritage breed needs help to survive.

A couple of breeds are new to us or otherwise noteworthy.

Cream Legbars have been a particular favorite of ours since we first ordered them as hatching eggs to start a breeding flock a few years ago. Although that project was derailed when the store’s roof collapsed in a 2014 snowstorm, we’ve enjoyed keeping one of the survivors and admire her good looks and other attributes. She gives us lovely, pale blue eggs and has tireless foraging habits. Best of all, this European breed reliably exhibits the ultra-rare autosexing trait that enables us to sort males from females at a glance at any age. That’s a big plus for individuals and communities that want to achieve independence from hatcheries and reach new levels of sustainability.

Though somewhat similar in appearance to Ameraucanas and Araucanas, this modern breed is unrelated to them, and their eggs lack the green tint of Easter Egger eggs. They can be difficult to identify by appearance, because the individual chickens can have virtually any feather color. We have recently begun keeping Whitings at home for evaluation, but if the claims are accurate, Whiting True Blue hold great promise as another reliable layer of blue eggs.

Our customers searching for pets and child-friendly breeds have usually done some research and are drawn to breeds identified as being especially docile. In this case, “docile” may refer to ease of human handling, but it may also indicate that they are easily dominated by other breeds in a mixed flock. Perhaps a more specific term for a good pet chicken would be “tame,” which better captures our desire to handle and interact socially with chickens as we do with other domestic pets. It’s been our experience, however, that individual chickens of any breed can be tamed by frequently and gently handling them as chicks and teens as well as hand-feeding the adults, but it’s true that some are easier than others. Along with the best general breeds for backyard chicken keepers, we recommend several others for those who are more interested in companionship than egg production.

Plump and Pleasing Balls of Feathers

• Can be kept in a small yard

• Low flyer that stays within fence

• Very broody, good hen for hatching eggs

• Not a good forager, comparatively gentle on gardens

• Produces few eggs

• Robust and cold hardy

• Prone to overheating

• Hardy appetite and low activity can lead to obesity

Cochins are astonishing: large, absurdly round, and comically covered in feathers on almost every surface, including heavy feathering on the tops of their feet and their legs. The Cochins we’ve known are dense, warm mounds of soft feathers that genuinely seem to enjoy interacting with humans, almost like a dog or cat. We suspect that this apparent affection is only partially because of breeding, and more likely a byproduct of their slow, earthbound bodies that make it impossible for Cochins to evade the grasp of their keepers, and in this way they become accustomed to handling. They never protest being picked up and hugged, and their plush feathering positively screams, “Pet me!” These low-flying birds are disinterested in flight when food is around, so they’ll stay put in almost any pen. In fact, they are often too heavy to reach high perches, so be sure to place theirs at 2 feet or lower.

The arrival of Chinese-bred Cochins in Britain in the nineteenth century ignited the poultry craze that still reverberates today. The early crosses are the origins of many of the well-known heritage breeds. It appears that Cochins were originally bred with ease of handling, or possibly even petlike tameness, in mind, as they are supremely well suited for it. Nevertheless, most hens will produce a few eggs each week in nice weather. We recommend pairing them with a couple of hens of other docile breeds that lay consistently if you also want eggs.

Their feathered feet can become encrusted with mud, making them susceptible to infection and foot diseases, but covering pens in rainy climates and good litter management can help keep problems at bay. You can soak affected hens and trim their feathers if necessary to remove mud and debris. In addition, in hot weather, it’s advisable to clip the fuzz under the tail and around the vent to keep the area clean and less prone to fly strike.

Cochin chicks are known to pile up as they sleep, suffocating each other in extreme cases. This is often caused by competition for a small spot of warmth in the brooder and can be prevented by warming a larger region more evenly—but avoid heating their food and water.

Like any quality collectable, this breed is coveted for its many desirable color variations and unique forms. For starters, their amazing plumage can comprise virtually every pattern and color—you could almost match it to your décor. Many colors are also available in bantam size in frizzle, a quirky, kinked feather type that also helpfully eliminates any remaining possibility of flight.

Cochins International maintains a fantastic website that offers a remarkably complete guide to caring for these unusual chickens and their special needs.

The Golden Retriever of Chickens

Orpies come in a variety of colors, but by far the most popular is the buff, with lovely yellow-gold feathers.

• 7 to 8 pounds

• Moderate layer of light brown eggs, may lay sporadically through winter

• Prone to broodiness

• Matures quickly

• Well adapted to small spaces

• Good breed for colder climates

• Gets along well with flockmates

The Buff Orpington is at the top of most lists of chickens to keep as pets, though we’ve found them unremarkable in this regard. Before you send us an angry e-mail in rebuttal, keep reading. We have seen many marvelous pet Orpies—but it’s a matter of which came first, the reputation or the reality. Most other breeds become just as tame when in the care of the type of person who likes to hug chickens. That said, we will concede that they are better layers than Cochins, though most Orpingtons are being bred as pets these days, and scant attention seems focused on preserving or enhancing laying abilities. Nonetheless, we appreciate the Buff Orpington for her color, good looks, easygoing personality, and winter hardiness.

The breed was developed in England by crossing a Minorca with a Black Plymouth Rock. At one time, Orpies were champion layers, capable of cranking out more than 300 eggs a year, but the breed has since declined shockingly in productivity as a result of careless breeding.

If you can find a quality breeder, Orpies can be spectacularly attractive—almost as round and statuesque as a Cochin without the sometimes problematic feathered feet. Seek out a color variant, as these tend to be more carefully bred—and satisfying. The Lavender Orpington is the most sought-after novelty color these days, but the breed is also available in black, white, jubilee (speckled), spangled (mottled), and probably a few more.

We’ve had better luck finding good layers among their cousins from down under, the Australorp (the Australian Orpington breed), a cross of the Orpington with the Rhode Island Red and several others.

We are often asked by customers whether it’s okay to mix chicks of different breeds, to which we respond, “Why would you not?” Although breeders and serious livestock folks have good reasons for keeping pure flocks, diversity has many advantages for the backyard chicken keeper.

Try combining breeds by selecting those with complementary habits. For example, keep hens that will lay moderately year-round with others that are more seasonally abundant to ensure a steady supply of eggs throughout the seasons. Or combine strong layers with more petlike breeds. Having a diversity of breeds enables you to learn firsthand about behavior differences and see how well each breed is suited to your environment and lifestyle to inform future selections and recommendations.

The distinct egg colors from a variety of breeds also make for a stunning egg basket, and the rainbow of egg colors are also useful for tracking the laying tendencies and output of the individuals in your flock. If one of your motivations for keeping chickens is the delicious eggs they produce, you may be surprised to learn that eggshell color has no direct effect on flavor (although fans of particular breeds such as the Maran may disagree), and the color of the hen has nothing to do with the color of her eggs. Egg flavor is one variable you can safely cross off your list when deciding which breeds to seek out.

Urban flocks are typically prohibited from including roosters, and even larger rural flocks need only a few, if any, to sustain them. Accordingly, female chicks that have been pre-sorted from their male counterparts are desired by practically everyone who keeps chickens to produce eggs. Sounds straightforward, but the difficulty arises because male and female chicks within most breeds look identical until they have matured and it’s too late to sort them. To offer their customers all-female chicks of most breeds, hatcheries must rely on trained personnel to isolate them from males based on minute differences in their sexual anatomy, visible only briefly after they emerge from their shells.

Some breeds, however, helpfully exhibit some degree of sexual dimorphism (physical differences between sexes) in feather color or pattern that makes sorting by early feathers alone possible, though not highly accurate. Hatcheries produce chicks with more reliably distinct markings by crossing breeds in specific ways to create sexlink hybrids.

The best-known examples of sexlinks are the gold sexlink, black sexlink, and red sexlink (sometimes sold under less racy-sounding names, such as Gold Comet). None of these chickens are true breeds, however—they are first-generation (F1) hybrids, and mating them will produce unpredictable results, both in terms of feather sexing and other important traits such as egg production.

Very early feather differences have been stabilized in some breeds to the extent that they are autosexing, meaning that this trait will reliably appear in each generation they are bred. Such breeds include the Cream Legbar and Bielefelder.

Our first chicks were a somewhat impulsive purchase. Sure, we did plenty of reading, formed opinions about which breeds seemed best, and usually had some sense of how many adult birds would fit in the coop we were planning. But when the fateful day arrived, it took only one peek into that first bin overflowing with fuzzy, colorful baby chick goodness to kiss those plans goodbye. We wanted them all! This is how many a beginner finds herself sheepishly returning to her car, balancing a huge sack of feed in one arm and a small box brimming with twice as many chicks as originally planned in the other.

Even the most experienced chicken keepers find their springtime visits to the brooders at our store practically irresistible. If we listen closely, we can hear their rationalizing above the din of tiny cheeps: “There’s always room for a few more,” or “We’ve got all of the gear already—might as well use it!” And my personal favorite, “I’ve been looking for this breed for years.”

Take a moment to slow down and consider your motivation for keeping hens in the first place. And remember, whether you’re establishing a new flock or adding a few fresh hens to boost egg production, overpopulation is an invitation for trouble of various sorts. After many years, Robert can scan a backyard, size up the coop, tug on his beard thoughtfully, and intuitively arrive at a number: “You can have up to six chickens in here, but you seem like a busy family and I’d suggest four. If the kids help and your neighbor over there will watch them when you’re gone and chip in on the feed bill for some eggs, you can handle six.” Making this judgment for yourself requires evaluation of available time, feeding resources, and the amount of both yard and coop space you can dedicate to the new additions. Feeding and time constraints are mostly cost-driven factors, but most of us can use a little help sizing up our spaces.

Coop size itself is seldom the most limiting factor, considering that chickens require little room for sleeping and laying. Each hen needs only 8 to 12 inches of space on a roosting bar, and a 4-by-4-by-4-foot coop can include at least two bars if they are offset and at different levels—enough to house eight to ten hens and three nest boxes. This density comes at a maintenance cost, however, because poop will accumulate at an alarming rate from so many birds, necessitating near-perfect ventilation and frequent cleanings to maintain low ammonia levels and a healthful condition within. If pressed to provide a formula, we’d say that each standard-sized hen requires a minimum of 8 cubic feet of coop space, but you’d be wise to make it 12. An often overlooked, yet crucially important, limitation on flock size is the run and foraging area.

| Coop size in feet (W×D×L) | Maximum capacity | Preferred capacity |

| 4×4×4 | 8 standard / 10 bantam | 5 standard / 7 bantam |

| 4×4×6 | 12 standard / 16 bantam | 8 standard / 12 bantam |

| shed, 8×8×8 | 24 standard / 32 bantam | 16 standard / 24 bantam |

A flock of sixteen hens may fit comfortably within a modest coop shed but will wreak havoc on a landscaped yard if they are allowed to run amok there daily. We figure that a 4-by-8-foot stationary run is the bare minimum for two or three hens, and they’d be far healthier and easier to care for in a much larger area, ideally 25 to 50 square feet per bird. If you don’t have that much land to dedicate to a run, consider a mobile coop that can spread its impact over a large area while maintaining a compact footprint.

We’ve long wanted to establish a self-perpetuating flock of heritage, dual-purpose birds at home to produce both eggs and meat. The problem has been the rules, common to most cities, prohibiting keeping of the roosters that we would require for breeding.

We’ve considered trying to game the system a bit by keeping a few young roosters just long enough to breed. When they’re young, they don’t crow quite as enthusiastically as they do when they get older, so in theory they wouldn’t bother the neighbors enough to report us (again). Our idea is to start with two or three male chicks of a desired breed late in the growing season—late September or early October in our area. They’ll be fully feathered and will have gained enough size to survive outside by January but will not reach sexual maturity (and get noisy) until around March, when our hens, kept year after year, begin laying in earnest again. At that point, hopes high, we’ll start pulling a few eggs from the nest each week and popping them in our incubator or under a broody hen. After we have confirmed the fertility of six to twelve eggs, we’ll harvest or relocate (if our daughters protest too much or for further breeding if they prove to be exceptional) the now loud and illegal roosters before the neighbors decide they’ve had enough of nature’s alarm cock (pun intended).

By nature’s design, about half of the chicks we hatch will turn out to be roosters. Of these, we will eat or relocate all but the finest two, which will be ready to breed by September, starting the cycle over again. As needed to replace lost hens, plan for succession, or expand the perennial hen flock, we can keep one or more of the female chicks and the rest can be sold or given away.

If the plan works, we’ll enjoy a lovely flock of dual-purpose, heritage chickens genuinely breeding like a real flock. If not, it may be time to switch to plan B: find an urban rooster stud service!

On Kauai, chicks must grow fast and move even faster to keep up with their busy and highly mobile mamas. With abundant year-round forage, warm daytime temperatures, and the protection of their mother’s downy belly nearby, these chicks live in ideal conditions for their growth and behavioral development—that is, if they manage to avoid being eaten by an egret, bullfrog, dog, or cat. Compared to the Hawaiian chicks, hatchery-bred chicks are hothouse flowers, and we are their gardeners. But chicks are more resilient than they seem, and as long as you remain vigilant and follow some basic guidelines, your chicks will thrive.

Chicks are easy to care for indoors in a brooder but can be dusty. Don’t brood your chicks in areas near where food is prepared, in sleeping quarters, or in other places where the brooder could pose a health or cleaning issue. A basement, mudroom, spare bathroom, and cool garage are all good bets. Be sure to locate the brooder near an outlet to avoid foot-tangling extension cords when possible. Regardless of where you put the brooder, you’ll appreciate having a fairly large spot that’s easily accessible.

Don’t think that you can brood young chicks outdoors, even in the summertime. The primary advantage of brooding them in your home is the steady, moderate temperature and the fact that you’ll be in close proximity—a big advantage for maintenance and monitoring for potential problems. The exception is using a spare coop for a transitional brooder, which offers welcome relief from the unruly antics of teenaged chicks, typically kept inside until they reach eight weeks or so.

In the mood to brood! A good brooder setup, like this one in a galvanized metal stock tank, offers a sturdy enclosure, clean water, absorbent litter, and a carefully placed source of regulated warmth.

Although most chicks are fine in brooders made from a large plastic tote, and dog crates are also a popular choice, something as spacious as a large cardboard box offers your little ones the room they need to regulate their own body temperatures, stretch their legs and wings, and practice natural behaviors such as foraging and dust bathing. A large box will also help you maintain ample separation between a heat source and the chicks’ food and water, avoiding the warm and damp conditions that incubate pathogens. A large brooder box also gives your chicks time to grow larger before you move them outside, which is particularly beneficial if you will be integrating them with adults.

Our hands-down favorite jumbo brooders are galvanized metal stock tanks, often sold at feed or farm stores and used to water animals. In the urban landscape, you’ve likely seen these deep metal tubs used as garden planters—or as bathtubs for cigar-chomping cowboys in old westerns. They are an ideal size and are extremely durable and not flammable, an important consideration when you’re using heat lamps to keep your chicks warm. In a pinch, and with a little imagination, rabbit cages and other pet gear can also be repurposed, but the fact remains that bigger is better when it comes to brooders.

Consider hazards within your home when placing your brooder, and keep a few easily overlooked hazards in mind.

• Dogs and cats, even when supervised, may suddenly attack or accidentally injure chicks. Although they may look cute together, it’s better to keep them separated.

• Children are ideally suited to be assistant chick caretakers, but they must first learn safe handling skills and safety procedures.

• A fall can be fatal while you’re holding a delicate chick; tripping over a brooder box on the floor can also be hazardous to both you and your chicks.

Screened wood shavings used for horse stalls or small animal cages are commonly available litter materials that work well. We avoid cedar, however, because it can be toxic to young chicks—look for pine, poplar, or aspen shavings. Purchase enough shavings to fill the bottom of the brooder 2 to 3 inches deep.

Our favorite medium to scatter on the brooder floor is coir, a highly absorbent material made from coconut husks. We originally found it marketed for reptiles, but it makes a superior, highly absorbent litter as well. Look for the coarse, chunky grade sold for horticultural use and reptile bedding. Coir is sold in compressed bricks (to reduce shipping cost) in two weights: a dry, larger chunk kind often labeled as husk chips, and a fine, shredded fluff. The chunk type is far easier to break apart when dry than the fine grade, which must be wetted prior to using. We recommend the chunk type, because moistening the shredded coir bricks defeats the coir’s utility for chicken litter. The chunky stuff holds plenty of moisture and is a prized addition to the garden as well—before or after serving its time in the coop. As with wood shavings, coir should be spread to a depth of 2 to 3 inches.

As quaint as it looks, straw should never be used to brood chicks. It usually performs poorly and often harbors mites. This also applies to the interiors of all but the largest coops. Straw is great stuff for outdoor runs, however, where it helps to control odor and combat mud.

Coconuts are a major cash crop in tropical countries, particularly India and Indonesia, where this versatile fruit is used to produce both food and fiber products. Millions of pounds of coconuts are processed each year, creating mountains of coir fiber behind processing plants.

Having raised a few dozen of our own chicks to maturity and after tending to hundreds more at the store, we confidently believed that we were doing it about as well as possible and thought there was little room for improvement. But as we reflected on the lessons we learned from the Hawaiian chickens and recent changes in medication regulations, we began to suspect that there was more we could do during this crucial period of growth and development, from hatch to about twelve weeks, to lay a foundation for lifelong chicken health and resilience. As it turns out, the missing piece of the puzzle would come not from our chicken-keeping experience, but from an entirely unexpected source: our backyard beehives.

Honeybees gather plant resins and use them to produce propolis, a sticky substance known to possess antibacterial properties. We read with great interest recent findings that revealed how propolis conveys social immunity to the entire colony, enabling individual bees to invest less energy in their immune systems. We knew intuitively that a similar effect must protect wild chickens, an insight that could provide a new approach to how chicks are brooded at home.

To explore our hypothesis, we perused scientific research, skimmed a few old farming manuals, and attempted to catch up with the efforts of the folks who share their approaches and debate topics like this online. We concluded that wild chickens also gain social immunity from the microbiome (the microorganisms in a particular environment, including the body) of their flock and its environment and that some of these benefits could be simulated by chickens keepers, similar to the way farmers traditionally raised several generations of healthy chicks on the same litter.

We’re not suggesting that you save soiled litter from your brooders. It’s far easier and more predictable to create living litter using materials that help fresh litter function more like a naturally aged material. Based on our research, we now recharge our home brooder with a few ounces of biochar (a form of charcoal that neutralizes toxins in feed and improves litter conditions) and several ounces of activated beneficial microorganisms (such as EM, a proprietary blend of beneficial microorganisms) incorporated into coconut fiber, changing it only when necessary, if at all. Though it’s difficult to confirm that we have seeded our chicks’ guts with healthful fauna, we know that we’re cleaning the brooder less often!

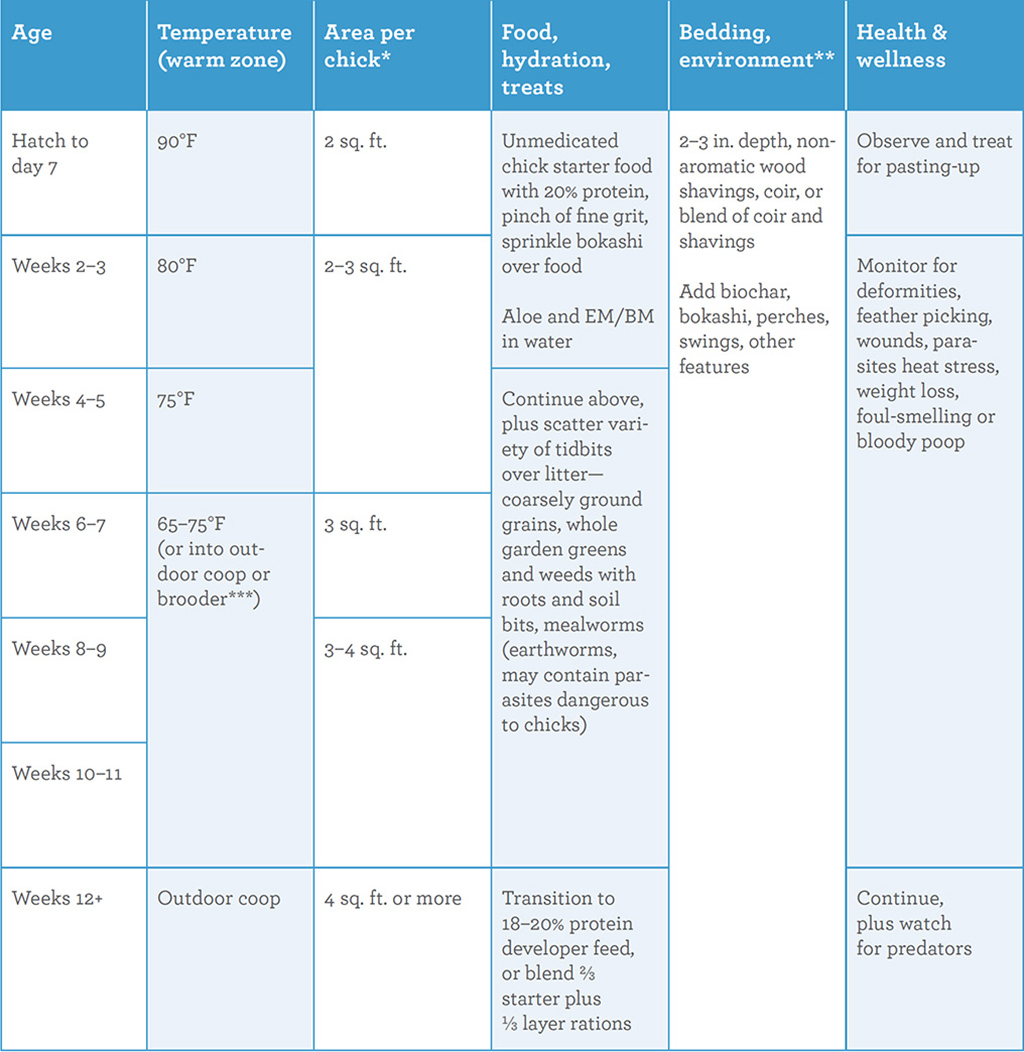

The following table summarizes our current (and evolving) blend of standard, new, and experimental techniques for living litter chick care.

*More is better. We often exceed this density at our store without harm, however, by monitoring and using other management protocols, including cages that enable the poop to drop through the cage floor into a tray below.

**Assumes use of nipple waterer for chicks that allows for our litter management approach. Standard litter management will require more frequent changes.

***Small numbers of teenage chicks will need moderately warm night temperature or a heat lamp to keep cozy outside in a coop or brooder, but five or more can huddle in cool nights and can go as early as five weeks old in suitable conditions.

Biochar is food-grade charcoal produced by burning wood or other carbon sources in a reduced oxygen environment. It’s not permitted as a commercial feed ingredient because it can mask the presence of contaminants, but you can add it to food and litter to protect both from many toxins. We sometimes sprinkle biochar on chick and adult hen food, but we use it mostly as a booster in our coir-based litter. Biochar is a powerful odor and ammonia absorber, and we are convinced that it is helpful for maintaining healthy litter conditions, particularly when litter gets deep and ages. The hens actually seem to seek out and eat the biochar in the litter, perhaps using it like grit, scratching and fluffing the litter in the process in a way that helps maintain healthful conditions.

The traditional function of litter in a brooder is to absorb moisture and keep odors in check. Although a variety of materials are effective, all seem destined to find their way into the drinking water as the chicks kick up litter while practicing their foraging and dust-bathing skills. More than an annoyance, the resulting stagnant and poopy water, coupled with the warmth of the brooder, has the potential to encourage growth of pathogens that cause illness and sap vitality.

Although the risk of hazardous water contamination is lessened by raising the water above the litter, it is not eliminated unless it is coupled with the use of drinking nipples, which are designed to release small amounts of water on demand from a reservoir. This system relies on gravity and the instinct of chickens to peck at shiny and colorful things.

Until recently, if you wanted to use nipple waterers with chicks, you had to make your own device using individual nipples purchased for custom applications. Small nipple founts are now available to purchase and are the perfect size for brooders. To ensure hydration for our chicks, we start the first day with a regular fount plus a nipple fount in our brooders, and then we remove the regular fount the next day. Nipple waterers are not only very efficient, but because they are installed overhead and rarely, if ever, leak, they have essentially eliminated the problem of poop commingling with drinking water and remaining there to fester. Drinking nipples are the secret weapons that enable farmers and chicken keepers to let their litter accumulate without forcing their livestock to drink warm poop tea. We strongly recommend their use; otherwise, the usual admonishments to raise the water above the litter and clean it often apply to the living litter method. Whether you use nipples or an open waterer, any unpleasant odors from the brooder are a sign that something is amiss and the brooder needs cleaning.

Chicks need light to stimulate their pituitary glands for proper growth and development. Natural, indirect light provided by a nearby window is good, but avoid direct sunlight that could overheat them. Windowless basements, which are ideal locations in other respects, are too dark unless you add artificial lighting from broad-spectrum lights that mimic natural sunlight. Regular light bulbs will work in a pinch, but we don’t recommend using them as a source of light, or warmth, in your brooder. Light sources should be put on a timer that will turn them on and off to simulate day and night.

Chicks also need supplemental warmth to maintain their body temperatures and metabolize their food properly. This is naturally provided by the downy feathers of mother hens, but you can provide an artificial source with an infrared heat bulb in a heavy-duty lamp base positioned above the brooder. These lamps and bulbs are often sold in feed stores and hardware stores, especially in the spring. Hang the lamp by its cord, or use the supplied clamp to attach it over the brooder. Set it at a good distance to produce a warm zone in part, but not all, of the brooder at the appropriate temperature for the chicks’ age. For warm locations such as inside a heated home, use a 100-watt infrared bulb; for cool areas such as a basement or garage, use a 250-watt infrared bulb. Because these heat sources need to remain on for twenty-four hours a day, use red infrared heat bulbs to avoid interfering with light cycles; the red bulbs may also help reduce aggressive behaviors.

If your brooder is large enough, the heat source distance and brooder temperature need not be as exact as they would be if using a small brooder, because the chicks will have room to enter and exit the warm spot to regulate their body temperatures, similar to how chicks use a mother hen’s warm belly. Try a combination of thermometer and chick behavior to determine setting and distance. If the chicks avoid the warm spot completely, raise the heat source to lower the temperature; if they huddle together under the warm spot and seldom leave, lower the heat source to provide more warmth. A large brooder and a warm zone also enable you to place food and water in a cooler area to keep it fresher.

Infrared bulbs emit lots of heat, but true infrared heat sources are a unique technology that warms bodies, not the air in between the bulb and the bodies. The bulbs are superior for warming chicks, but if you put your palm in front of one to judge the heat output, you might not feel as much warmth as you’d expect.

Always use caution with high-wattage bulbs—especially the 250-watt size, which is hot enough to ignite litter and cardboard and melt plastic. Suspend it above the brooder and avoid clamping the lamp to flimsy sides, and never remove the bulb guard that is sold with most quality lamps. Always use a lamp rated for high wattage bulbs in an appropriate receptacle.

A good infrared lamp is more expensive than a regular brooder bulb and lamp, but it will be long-lasting and durable, so you can use it on your third, fourth, and fifth expansions of the flock. It will still be serviceable the next time you brood and can be used safely and efficiently to warm adult hens in their coop.

Another warm alternative that’s discussed at online chicken-keeping forums is the electric hen, which provides a little heated shelter for chicks. You can purchase ready-made electric hens or make your own. Several online sites offer instructions on how to make electric hens by placing an electric heating pad over an arched wire screen or other heat-resistant support that’s sturdy enough and high enough for chicks to gather underneath. Use a name-brand, moist-heat–rated pad without the auto-shutoff feature, and make sure it’s in good condition, with no tears in the plastic pad cover. It’s said to be safe for use in this application, even when sprinkled with a protective layer of litter on top—as always, use caution when repurposing an item originally intended for a different use.