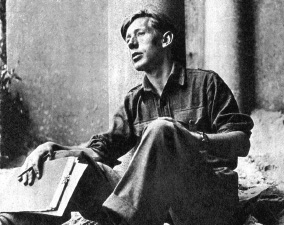

Laurie Lee

Laurie Lee, explorer of a lost rural England, died on May 13th 1997, aged 82

The England that Laurie Lee wrote about so evocatively no longer exists. Perhaps it never existed, except in his imagination. In “Cider with Rosie”, his best-known book, there is, for example, a certain scrumpy haziness about this temptress of the haystacks, who “baptised me with her cidrous kisses”. The Rosie of the book shyly identified herself after it became a bestseller. They were marvellous days, Rosie recalled, but she dismissed the idea that she and Laurie had been “sweethearts or anything”. Neither had she drunk cider with him, or anyone else. “I suppose all writers exaggerate,” she said. Still, admirers of Laurie Lee’s writing have never been put off by mere realities. He thought of himself primarily as a poet. Facts should not get in the way of the words.

In his next memoir, “As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning”, Mr Lee is off to Spain. As in England, the roads are “innocent of oil and petrol” but, even better, there is an abundance of generous Rosies. Mr Lee started out with no Spanish other than the words for “May I have a glass of water, please?” But this, together with scraping a tune on his violin, seemingly provided for his needs. Merrie old England and funny foreigners: a reader was blissfully comfortable with Laurie Lee.

Artfully, though, he wove into his memoirs the exemplar of the lad from a humble background who made good. The Anglo-Saxon virtues of “hard work and necessary patience” saw him through. His father had two wives who between them produced 12 children, eight of whom survived. Lee senior abandoned the crowded Cotswold cottage and ran away to London where he became a civil servant, sending home £1 a week. Laurie left school at 14 and took a number of undemanding jobs. Then he, too, left “the honeyed squalor of home” in the village where “everyone minded everybody else’s business”, and did not see it again for 20 years.

Fame did not come quickly, and almost did not come at all. During the second world war Mr Lee wrote government pamphlets and helped to make propaganda films, and published several books of poems, which were well regarded at the time. Cyril Connolly, the most influential literary critic of his day, encouraged him. Mr Lee considered his poems his best work, but this view is not now widely shared. Nothing of his was thought by Philip Larkin to be worth including in his “Oxford Book of Twentieth Century Verse”.

The publisher of “Cider with Rosie” in 1959 was at first reluctant to take it on, doubting that it would sell well, despite the blurb Mr Lee wrote for its dustjacket: “Should become a classic”. Even the critics who gave it good reviews could not have predicted that it would sell more than 6m copies around the world (in America, rather less invitingly, as “The Edge of Day: A Boyhood in the West of England”).

Here on offer was a lost rural world, but one that seemingly could still be reached by using the most primitive of transport, your legs. When Laurie Lee had left his village he had walked to London. He walked through Spain and a dozen other countries. Every born-again walker owes something to Mr Lee. Not

surprisingly, the rosie hue of his writing has been welcomed by the tourist industry, which thrives on nostalgia. “Cider with Rosie” made Slad, Laurie Lee’s Cotswold village, world-famous. Mr Lee is among those, such as Hardy, Hemingway and the Brontës, who have established literary landmarks. After visiting Slad and popping into the Woolpack inn for a Rosie special, a Lee pilgrim might nip over to Almuñecar, a fishing village and the scene of an episode in his Spanish book, to look at the statue put up in his honour.

This remarkable achievement came from a modest oeuvre: mainly three bits of biography (the third was “A Moment of War”, about his experiences in the Spanish civil war, when he fought briefly against the Franco forces) and his poems. Laurie Lee was not contrite about writing slowly (with a 4B pencil). Barbara Cartland and Compton Mackenzie had written hundreds of books which had been forgotten, he said. His few were remembered. Nevertheless, he took his success without fuss. The main gain, he said, was that he could now afford whisky.

After becoming famous, Mr Leereturned to Slad and bought the cottage of his childhood. But he kept a flat in London. It was hard to write in the country, he said. If it was a nice day you would lie in the long grass or some friends would arrive and you would go to the pub for a chat. “And that’s the day gone.” But although an urbanite by adoption, Mr Lee liked to have reassurance that the country, his country, awaited him when he needed it. He joined with other villagers of Slad to oppose, successfully, a proposal to build a housing development on a meadow near the village. In such places, he said, the young decayed, “imprisoned by videos and computer games”. They did not have the feeling of community he had known. No, he did not think Rosie would have cared to curl up in front of the telly.