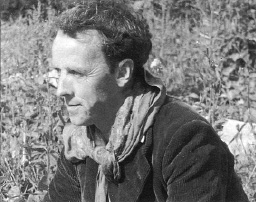

Ronald Lockley

Ronald Mathias Lockley, a protector of nature, died on April 12th 2000, aged 96

The danger of writing about Ronald Lockley is of presenting, probably unfairly, a portrait of an oddity. He believed he had a gift of communicating with animals. Writing in The Economist in 1979, an exasperated reviewer of one of Mr Lockley’s books said he “should have kept off imaginary conversations with dying killer whales”. But the old whale Mr Lockley befriended did have some strong points to make about polluted oceans. And if it was odd to talk with whales, and indeed with many other creatures, it was an affliction that Mr Lockley shared with Aristotle and Plutarch, to drop a name or two.

Anyway, Mr Lockley had pretty convincing proof that giving human characteristics to animals was fairly widespread. In 1964 he had published “The Private Life of the Rabbit”. This study of the habits of the wild rabbit gathered by Mr Lockley persuaded Richard Adams to write “Watership Down”, a kind of Disney story for adults, which became an immediate bestseller. Anthropomorphism, as it is bleakly known, was decreed to be free of health risks.

The two men became friends and went on an expedition together to the Antarctic. “I can’t recollect that we ever had a disagreement,” Mr Adams said last week. However, “Watership Down”, which gave rabbits human characteristics and humanlike problems, was far removed from Mr Lockley’s view of the animal world. “Watership Down” is a novel, a thriller set in the mean streets of the warren, requiring considerable suspension of belief. Mr Lockley’s request was more subtle: for a suspension of hostility by man towards nature. Like humans, he said, other creatures had “a measure of reasoning and individual action”. A lecture Mr Lockley gave from time to time was entitled “The seabird as an individual”. One of his books (he wrote about 40) was “Man against Nature”, in which he chronicled the destruction of animals and plants in Australia and elsewhere in the South Pacific.

Ronald Lockley felt most comfortable on an island. In 1927, when he was 24, he rented Skokholm, a small deserted island off Wales. It had few material comforts. The reason it was deserted was because the previous inhabitants could no longer stand the battering of Atlantic gales and the loneliness. Even fishing was hazardous off the rocky coast. But Mr Lockley and his wife repaired a farmhouse, using timber from a wrecked schooner, and coal from her cargo to keep warm. Fresh water was mostly provided by the relentless rain. Before coming to the island he had worked on a small farm, and was used to improvising.

He studied the real owners of the island, the seabirds, and wrote books about them. One was called “Dream Island”. In 1933 he founded Britain’s first bird observatory on the island, where migrating birds were trapped, ringed and released. Skokholm, and Mr Lockley, became mildly famous. Scientists arrived to peer at the shearwaters and puffins. A film was made about the life of the gannet and won an Oscar as the year’s best documentary. Princess Elizabeth, later to become the queen, thought she would like a pet razorbill. Mr Lockley brought one

to Buckingham Palace, and on television was seen being attacked as he opened its basket. The king of Bulgaria turned up at the island, accompanied by a servant who carried a chair in case of royal exhaustion.

Mr Lockley inhabited his dream island until the second world war when he joined the navy and thought up ways to track submarines. After the war he bought a house on the mainland of Wales, where he did his study of wild rabbits. The problem was to get close to them. There had been rabbits on Skokholm, but they had resolutely kept their distance. Mr Lockley’s solution was to fit glass panels to a warren, and for four years he studied such matters as overcrowding, the effects of myxomatosis and how the males defended the warren against stoats.

He thought he would like to live on an island again. But not Skokholm or any Welsh islands. Wales, where he was born, was, he judged, no longer protecting its environment. He tried to stop an oil refinery being built in western Wales, was unsuccessful, and that was that. He visited many islands that seemed interesting, from the Kuriles to French Polynesia. He settled in New Zealand. The country is overrunwith rabbits, and the New Zealanders hopefully asked Mr Lockley if he could advise them how to get rid of the pests quickly. He could not. Rabbit-killing viruses were cruel and did not work, he said. Try to control the rabbits by traditional methods and be patient, he said.

Most New Zealanders are happy to be impatient and like to think that they are as modern as tomorrow, but outsiders insist that they are not, and that is their charm. Mr Lockley said that New Zealand was the last place of any size to be colonised by humans, and it was still in the happy position of having to catch up. “Go slow, New Zealand, go slow,” Mr Lockley told his adopted country. It won’t, not willingly. But New Zealanders liked Ronald Lockley, admired his reputation as a protector of nature, and would never laugh at him just because he talked to whales.