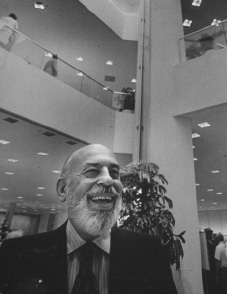

Stanley Marcus

Stanley Marcus, purveyor of extravagance, died on January 22nd 2001, aged 96

There comes a time in the life of the average billionaire when money ceases to be important. Suddenly it no longer seems to make the world go round; it has become quite boring. Stanley Marcus was sympathetic to the problem and sought to rekindle interest in possessions among those who wanted for nothing. “The people who come here actually need very little,” he said with the air of a kindly doctor dealing with a particularly difficult patient. What Mr Marcus set out to do at his shop Neiman Marcus was to turn the sufferer into a “wanter”.

Sometimes there was a quick success, especially if the patient were male, and billionaires usually are. “I’ve never found a man who needs a necktie,” said Mr Marcus. “But he may be fascinated with the colour, or the design, and he wants it.” But few cases were that simple. What about private aircraft? Got one, got several. But Mr Marcus was offering his and her matching aircraft. They would be the talk of the billionaire set. His wife would be charmed and especially attentive. They could keep boredom at bay for a week.

His and her aircraft, introduced in 1960, were followed by his and her miniature submarines, hot-air balloons and matching camels. Mr Marcus acquired two Egyptian mummies, established that they were male and female, and they too were resurrected into modern commerce. He sold Chinese junks and solid gold needles whose eyes no rich man could enter. His barbecues were silver plated and came with a live bull. His bathrobes were made of ermine. He is said to have discovered the shahtoosh, a sublimely soft scarf made in its original form from the neck hairs of Himalayan goats, and which in less exotic material has since become widely popular in high street shops. He never let up in his mission to save the very rich from the wasting disease of boredom.

The first Neiman Marcus shop was in Dallas, Texas. Cowboys and Indians were among the shop’s first customers. From these rough beginnings Mr Marcus sought to make the firm an American symbol of luxury living.

His father, uncle and aunt, of German Jewish stock, had started the shop. Young Stanley went to Harvard and on his return at the age of 21 became bookkeeper, salesman and much else besides. In his autobiography Minding the Store Mr Marcus gives the impression that he was not all that keen to settle down in a hick town after having been given a glimpse of a wider world of books and ideas at Harvard. But having decided to be the dutiful eldest son he set about transforming the family business into something beyond the confines of 1920s Dallas.

He started with the considerable asset that Texas, a state of oil and cattle, was wealthy, and growing wealthier by the day. The scruffy girl in gingham could be the daughter of a suddenly wealthy oilman. Today she was buying another cotton dress. Tomorrow she would want fashion. In those days Mr Marcus’s challenge was not to alleviate the boredom of the rich, but to keep up with the demands of Texans newly flush with money.

His weekly fashion shows were among the first in the United States. Eventually he introduced to Texas the great names

of European fashion, Chanel, Courrèges, Balenciaga. The bookish Mr Marcus became an attentive pupil of the masters, particularly Balenciaga, the Spaniard who was himself the mentor of many famous designers. “He will enhance your beauty,” Mr Marcus assured the matrons of Texas, “not dress you in ugly things, like some newer designers.”

At the same time as promoting high fashion Neiman Marcus expanded from a speciality shop into an all-providing department store. When in 1969 the Marcus family sold a controlling interest in the company to a conglomerate, Carter Hawley Hale, sales were more than $62m a year (equivalent to $300m today) and there were Neiman Marcus stores in cities across the United States. Under the deal Mr Marcus ran the business until his retirement in 1975, and continued to beinvolved in it into his 90s.

In later years Stanley Marcus became a much-interviewed guru of retail selling. It was almost like being back in Harvard, but now he was a professor, dispensing erudition, occasionally raising a chuckle from an attentive audience. “I have the simplest taste: I am always satisfied with the best.”

So where would you find the best, professor? Not, it seems, these days in department stores.

Department stores have become cumbersome and dull. They have lost their sense of excitement, of adventure. If you blindfolded a woman and dropped her from a plane into a shopping centre in America she wouldn’t know whether she was in Indianapolis or Minneapolis or wherever. She would see the same big stores, the same merchandise in the windows. A new fashion in Italy is faxed over from Milan to New York or Miami and it is knocked up and appears everywhere and becomes stale before it is even able to walk. Department stores are waiting to be re-invented. Starting out again, I’d learn from the boutiques, the small speciality shops that offer individuality.

It suddenly sounded as though Stanley Marcus was back in the 1920s, preparing to take on the world from Dallas.