George Melly

Alan George Heywood Melly, jazzman and writer, died on July 5th 2007, aged 80

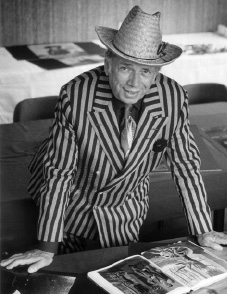

AMONG his many guilty pleasures – Marlboro Lights, Irish whiskey, bacon and eggs, blue jokes, smoke-filled dives where the music wandered on till four in the morning, voracious sex with good-looking men and women – George Melly especially liked to fish. The man famous for red, green and cream striped suits, red fedoras and a huge, rude, laughing mouth could often be found quite still, thigh-deep in the Usk or the Teifi, preparing to cast as soon as a bold trout tickled the surface of the water. And the singer whose party piece, when touring with John Chilton and the Feetwarmers, was to scamper round the stage and groom the clarinettist’s head during his rendition of “Organ Grinder Blues”, would admit that his thoughts on the river bank were of poppies, midges, Magritte and clouds.

And sex. This had been his driving force since his first schoolboy fumbles at Stowe, first rampantly homosexual, then generously heterosexual, among anchor chains and on Hampstead Heath, in the backs of vans and in glorious pulsating piles on the floors of stately homes. And there was, he confessed (being the most shockingly confessional of writers), sheer orgiastic pleasure in the tug of a bloody great fish, the line screaming off the reel, the catch leaping from the water in a shower of diamonds, the net sliding under it and the fish laid, beautifully marked, on the grass. Phew! Time for a ciggie.

But Mr Melly liked fishing for another reason. As a lifelong Surrealist, he was sure that the bizarre and marvellous lay in wait for him everywhere, and carried in his head a Surrealist motto, “the certainty of chance”. Chance might give him a fish with the next cast; and chance shaped his drifting, exuberant, deep-drinking life, from Stowe to the wartime navy to art-dealing to journalism on the Observer, through a rich cast of queens, hoodlums, sailors, old trouts, whores and martinets, until in 1974 the career of a risqué jazz singer finally hooked him for good.

He sang for 30 years, stoutly and louchely fronting the Feetwarmers at Ronnie Scott’s and round the country, until he had to growl his Hoagy Carmichael numbers from a wheelchair. Mr Melly was possibly the most popular jazzman in Britain, and certainly the most outrageous.

Like all the addictions of his life, jazz burst on him at school. A friend’s study; a gramophone; an old 78, and the voice of Bessie Smith, straight out of Harlem.

Gimme a pigfoot and a bottle of beer

Send me again. I don’t care.

Mr Melly sang Bessie, “Empress of the Blues”, more than anyone else. He would entreat her to possess him before a performance. But the Bessie that emerged from that quivering, beer-wet throat was partly a white, English, middle-class creature, drawn from music-hall turns and end-of-the-pier shows, dressed in bowlers and blazers, and with the plunk-plunk of a banjo never far away. Trad jazz, in the person of Mr Melly, Humphrey Lyttelton and a few others, limped through the 1960s and 1970s until out of sheer graft, longevity and good humour it came back into favour. He helped it survive.

Classlessness and anarchism drew him to jazz also. Though his background was

wealthy Liverpudlian, his inter-war fling with left-wing politics stayed with him for life. So, too, did other flirtations. On shore leave from the navy in “amusing” bell-bottoms in his roaring homosexual years, he admired a pimp encountered in Leeds in a mauve silk shirt and kipper tie, and the way Quentin Crisp’s painted toenails accessorised his golden sandals. The gay fetishes faded, though as “an old tart” he could always have his head turned by pretty boys; but sharp tailoring in eye-watering colours became his stock in trade.

This aesthetic streak pointed to yet another side of his sprawling personality. He knew about art, and had an eye for it, ever since his inclusion as a wide-eyed petit marin in the Surrealist circle round E.L.T. Mesens in Soho in the 1950s. On impulse he made surreal objects himself(a dead starfish caught in a mousetrap, a nude with Carnation Milk tins as her breasts), but he also learned to buy cleverly in a difficult market. One train trip back to Liverpool from London was spent in silent adoration of two new acquisitions by Max Ernst, propped on the opposite seat.

As old age advanced, Surrealism became an increasing comfort to him. It gave an aesthetic purpose to his multicoloured lines of pills, and to the hours spent in limbo in the scanner. Deafness reminded him of Surrealist word-games in which question and answer were unrelated, or only incidentally and wonderfully so:

What is reason?

A cloud eaten by the moon.

Fishing, too, was still a comfort. He imagined his cancer – for which he refused all treatment so that he could go on performing – as a tiny fish dangling at the end of his lung, wrinkling its whiskers, ready perhaps to be caught. And he often said that his favourite end, other than collapsing in the wings of a theatre with wild applause still ringing in his ears, would be to be discovered smiling on a riverbank with a big beautifully marked trout beside him, death and sex together.