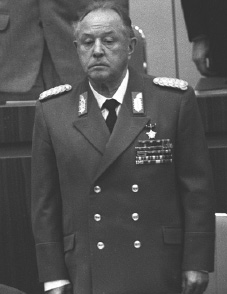

Erich Mielke

Erich Mielke, East Germany’s secret police chief, died on May 22nd 2000, aged 92

After the East German state collapsed in 1989, revenge was in the air. At the top of many people’s lists for retribution, if not lynching, was Erich Mielke, the head of the Stasi, East Germany’s secret police. He was put on trial for being jointly responsible, with the East German leader Erich Honecker, for the deaths of 49 people trying to escape to West Berlin over the Berlin Wall. The trial was abandoned, partly because the killings were proving hard to pin on those at the top, and partly because Honecker was dying, while Erich Mielke complained that he could not follow the proceedings.

Mr Mielke was put on trial again, this time, to many people’s astonishment, for murders he had been involved in back in 1931, in the days before Hitler came to power. On the orders of the Communist Party, he and a colleague had shot dead two policemen who had incensed the party by breaking up its demonstrations. Young Mielke had escaped, but the German police had never forgotten the murders of their finest. This time there was no problem of providing proof of his misdeed, and in 1993 he was sentenced to six years in prison; not enough, said some, but at least he had not eluded justice entirely.

Perhaps Erich Mielke was himself impressed that his police file had survived through more than 60 years of war and peace, passed on from regime to regime. It was a tribute to the thoroughness of German bureaucracy. Mr Mielke was an obsessive bureaucrat. His speciality was collecting personal data. Of course, all governments do this, democratic ones as well as dictatorships, as do commercial organisations; and laws are made to try to restrain their enthusiasm for intruding on the privacy of individuals.

Mr Mielke operated with few restraints. In 1957, when he became head of the Stasi, an abbreviation of Staats (state) and Sicherheit (security), it was just one of a number of bodies designed to protect East Germany against the western “imperialists”. Mr Mielke so expanded the Stasi that, by the time he was toppled some 30 years later, he was the most powerful man in East Germany after the party leader: “the master of fear”, as West German popular newspapers liked to call him.

Erich Mielke scrutinised the lives of East Germany’s 17m people with a thoroughness that probably even exceeded the Gestapo’s. No detail was too minor to be noted on the Stasi files. Political views of course, but also reading tastes and sexual inclinations, even a preferred drink. From a dossier, a decision might be made about a citizen considered a threat to the security of the state, and consequently jailed, or shot. When the Berlin Wall was built in 1961, as a result of Mr Mielke’s urging, the entire population became prisoners of the state.

It is estimated that some 2m people were informants for the Stasi at one time or another. Most of the files kept in the Stasi’s vast complex in Berlin’s Normannenstrasse have become accessible to those deemed entitled to view them. As a result people are distressed to find that close friends provided information about them; that there were treacheries even within families. Mr Mielke’s own reflections to his subordinates are there. One is, “All this twaddle about no executions and no death sentences, it’s all junk, comrades.” Sometimes he would leave his desk and conduct his own interrogations. “I’ll chop your head off” was one of his customary threats to anyone he suspected of betraying the party.

The Stasi tentacles extended into West Germany, where Mr Mielke had informants in many government ministries, among opposition groups, in NATO, American military bases, even in the churches. In 1974, the then chancellor, Willy Brandt, resigned after a Stasi spy was found to be working in his office. The East Germans knew about Helmut Kohl’s misdemeanours long before they were revealed to the world. Even those who loathed Erich Mielke acknowledged that he ran an extremely well-informed service. As more Stasi files are made public it may turn out that the East Germans were also privy to intrigues in other European countries whose participants would prefer to remain secret.

Yet there was a sort of innocence about Erich Mielke. He seemed unable to comprehend why anyone should want to be other than a communist. The party had always looked after him, recognising that there was talent in the poor boy from a Berlin tenement; giving him an education in Russia, followed by experience among the comrades in Spain and France. In East Germany after the war he rose swiftly in the Stasi until he was allowed to fashion it his own way. Wanting “to know everything, everywhere”, as he put it, seemed the

only way to protect the state. When an angry crowd confronted him after he was deposed, he shouted back, “But I love you all.”

In prison the unloved Erich Mielke was said to be cheered up when he was provided with a disconnected red telephone with which he could talk to imaginary agents. It was assumed that he was going mad, although sceptics, suspicious to the last, said that he was just feigning madness to avoid facing new trials.