Eric Newby

Eric Newby, travel writer and fashion buyer, died on October 20th 2006, aged 86

BY THE standards of many British explorers, Eric Newby was not particularly intrepid. He could not bear the thought of pain, and would faint away in any film that featured an operating theatre. Horses terrified him, especially when, in Italy, a reluctant mare he was riding was persuaded to clear a ditch by having a lighted cigarette inserted up its backside. Forced to sleep on rocks – to Wilfred Thesiger’s huge disdain – he would blow up an air-bed to cushion the ordeal.

But then Mr Newby did not see himself as an explorer in the Thesiger mould. He was a traveller to whom things happened, and he would set off in that inquiring, ill-prepared, innocent way that has characterised Englishmen abroad from Chaucer to Evelyn Waugh. He was an amateur whose 25 travel books – most famously “A Short Walk in the Hindu Kush” (1958) and “Love and War in the Apennines” (1971) – were full of serendipity and surprise. A sudden view of a ravine with a grey heron winging across it; the moon rising “like a huge rusty coin”; Parmesan cheese, eaten after days of hunger, with “hard, salty nodules” of curd in it; the shock of blue and green phosphorescence dripping from his oar. Possibly only Mr Newby could notice, while treading water off the east coast of Sicily in 1942 and trying to avoid being shot at by Germans, that the plume of smoke over Etna looked like the quill of a pen stuck in a pewter ink-pot.

Well-equipped he may seldom have been, but he was usually well-dressed. For Mr Newby had another life. For 20 years, to finance his travelling and writing, he worked in the garment trade. After helping run the family firm of Lane and Newby Ltd, Wholesale Costumiers and Mantle Manufacturers, he joined the John Lewis Partnership in the Intelligence Department, meaning that he checked whether trousers fitted or not. After this, he was promoted to “Model Gown Buyer”. If this life of pins and patterns seemed a come-down to a man dreaming of the Ganges or the Sahara, he certainly did not admit to it. To make “The Journey” as a sales rep through industrial Britain, rattling north overnight unsleeping in a third-class seat and then staggering up the back stairs of department stores with wicker baskets full of suits, was every bit as exciting.

Besides, he loved clothes. He had been drawn to travel in the first place, as a restless child growing up in suburban south-west London, by the pictures of foreign boys in petticoats in Arthur Mee’s “Children’s Colour Book of Lands and Peoples”. His first unaccompanied journey, following a Devon stream down to the sea through nettles and cowpats at the age of five, was made in brown lace-up shoes and “a hideous red and green striped blazer with brass buttons”. Apprenticed at 18 on a four-masted barque that ran the last great Grain Race from South Australia to Ireland, he first ran up the oily rigging, teetering 160 feet above Belfast, in grey flannel trousers and a Harris tweed jacket.

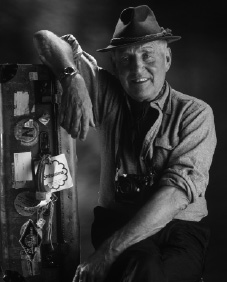

All this sounded rather upper class. And Mr Newby cut such a figure, handsome in immaculate safari suits and, in London, a trilby hat. He had a gentleman’s cavalier attitude to expenses when, from 1964–73, he was the travel editor on the Observer, and a gourmet’s approach to his later journeys. (“Had a delicious mini-picnic under a tree,” he noted during a bicycle ride through France in 1971; “small, ripe, melons and a bottle of cold Sancerre.”)

Yet he himself was “middle-middle class”. He had been to St Paul’s, not Eton, and had left school at 16 because his family could no longer afford it. His time as a prisoner-of-war, from 1942 onwards, was diverting to him not only because it led him to his future wife (a tall, blonde, determined Slovenian girl who came to visit him when he was transferred to an outside hospital) but also because he could observe those strange creatures, the English upper classes, up close. Before that he had mostly met them in Harrods, small boys like him braving the “unending, snowy-white wastes” of the Linen Hall and the “savannahs” of Model Gowns, “endless expanses of carpet with here and there a solitary creation on a stand rising above it, like lone trees in a wilderness.”

In his travelling life he had many a narrow escape. On the great Grain Race, he was almost washed away in a hurricane. Hunting with princes in Andhra Pradesh he was charged by a bear, but failed to shoot it because he dared not use a rifle (a .465 Holland & Holland India Royal) that had cost £800. In Italy during the war, a fugitive prisoner, he woke from a sleep on a mountainside to find a German officer standing over him. But the officer wanted merely to chat and catch butterflies. “The last I saw of him”, he wrote, “was running across the open downs with his net

unfurled ... making curious little sweeps and lunges as he pursued his prey.”

Mr Newby was often asked why he loved to travel. It was, he said, to do with being free. But his attitude to freedom could be ambivalent. Twice, when he had got out of prisoner-of-war camps, he found himself musing that “real freedom” lay back inside the fence. There was no need, he wrote, to worry about anything there: no need to work, to earn money, or to think about what to eat. Or, indeed, what to wear. n