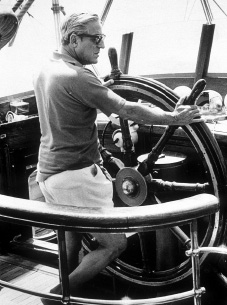

Stavros Niarchos

Stavros Spyros Niarchos, master of the high seas, died on April 16th 1996, aged 86

Tycoon, a word of Japanese origin meaning great prince, was often applied to Stavros Niarchos. The description was almost accurate. Mr Niarchos had a touch of greatness and lived in a style that few real princes can afford. There was, though, an amorality in his business dealings that a Japanese taikun might have thought not quite honourable. In 1970, when Greece was under a military dictatorship, Mr Niarchos, by then a major industrialist and the owner of the world’s largest merchant fleet, gave public support to the junta and was rewarded with control of a state-owned oil refinery. Nothing exceptional in such a deal, perhaps, for a conservative and a Greek patriot, except that, at the height of the cold war, the Niarchos shipping fleet was also distributing Russian oil around the world.

Mr Niarchos took the view that, as an international businessman, he had the right to trade freely. America, a citadel of free trade, could hardly disagree, but it frowned on a Niarchos deal that allowed Russian oil to be shipped to Cuba. Mr Niarchos had an equivocal relationship with America. His parents were naturalised Americans, but he was born in Athens, and stayed Greek. Much of his early business was done in America, but his ships were registered in Panama to avoid paying American taxes. In 1953, when he was accused of breaking an American law by getting control of ships prohibited to foreigners, he moved his American business to Europe. He kept a house in New York, one of several around the world, but his palatial home was in Greece, on an island he owned in the Aegean. His preferred company was titled Europeans.

Stavros Niarchos’s first job was as a clerk in a firm owned by his uncles, who were grain dealers. According to family legend, young Stavros persuaded his uncles to buy their own ships, making a big saving on grain imports. In 1939 he was given, or acquired, his own ship. In the second world war the ship was sunk in Antwerp harbour by a German bomber. Several other ships he later acquired were bombed, or sunk by submarines. The insurance money was the foundation of Mr Niarchos’s fortune.

After the war Mr Niarchos came by a number of Liberty ships, which America had mass-produced in great numbers and was selling cheaply or giving away. But many of the Liberty ships were worn out. They were welded together (rather than riveted) for speed of manufacture, and the welds sometimes came apart, sending the ship to the bottom. Mr Niarchos started to order his own ships, usually from Asian yards, where costs were kept down through government subsidies. He is sometimes credited with inventing the supertanker: of hitting on the idea that a ship with twice the capacity did not cost twice as much to build and operate. But it had long been realised in every area of manufacturing that fixed costs, particularly labour, do not necessarily scale up to the size of the product. What Mr Niarchos did was to apply this truism to transporting oil, which he was sure would overtake coal as the chief fuel in the rich economies. That was his vision. In 1956 he launched a ship (named after himself) of more than 47,000 tons, then the largest tanker afloat.

This was the forerunner of tankers of up to 500,000 tons. Shipping oil became one of the fastest ways to make money. After a few voyages the ship had paid for itself.

Although the Niarchos name is identified with ships (and, as it happens, his name means “master of ships”) much of his fortune was later diversified into property and elsewhere. At the time of his death the man who had once owned some 80 tankers, more than anyone else, was reckoned to have no more than Greece’s 15th largest merchant fleet. Because of his canniness he was able to survive the shipping slump in the 1980s.

One of his soundest investments was in paintings. Like other self-made tycoons, Andrew Mellon for instance, Mr Niarchos liked to load up with blue-chip art. He owned Manets, Cézannes, Picassos,Renoirs, and numerous others, modern but not too modern, that filled a warehouse. These expensive tokens of graciousness will now move to other owners until, to the dismay of dealers, they end up in museums, as the Mellon collection did. He had the other toys of the rich: a private jet, several yachts, one of them said to be the most beautiful in the world, and numerous racehorses. He was an impressive host: he introduced pheasants into his Greek island so that guests could have something to shoot at. He was married five times. The competition on the high seas that existed between Mr Niarchos and another Greek shipowner, Aristotle Onassis, seems to have extended into their private life. His fourth wife, at 56, was Charlotte Ford, aged 24, of the motor family. Shortly afterwards Mr Onassis was deemed to have outshone him by marrying Jacqueline Kennedy.

He will be missed, by a vast audience perhaps not much interested in tankers, even supertankers, but which was fascinated by this man who went shopping on a princely scale. Rich people, captains of industry, are commonplace. Tycoons are rarer. n