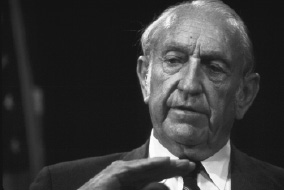

David Packard

David Packard, the inspiration of Silicon Valley, died on March 26th 1996, aged 83

At a memorial service for David Packard at Stanford, the university he credited for his start, more than 1,000 mourners showed up. It seems a lot of people credited him for their start, too. Mr Packard founded, along with Bill Hewlett, one of the most successful high-tech firms in history, Hewlett-Packard. (The order of names was chosen by the toss of a coin, but, as it turned out, in reverse order of influence.) More importantly, in a small garage in Addison Avenue in Palo Alto, California, the two men started what would become Silicon Valley.

It is hard, on reviewing Mr Packard’s life, to understand how this boy from Pueblo, Colorado, who liked to be in the open air and would spend some of his happiest moments driving a bulldozer on his ranch, could have inspired such digital-age icons as Microsoft’s Bill Gates, Intel’s Andy Grove, and Steve Jobs, Apple Computer’s co-founder. Mr Packard was always a gentleman, who insisted that his employees respect their competitors and never criticise them in front of customers. Today the business is full of predators, publicly contemptuous of their rivals, who preach such battlefield exhortations as “Eat lunch or be lunch” and “Only the paranoid survive”.

As a child, Mr Packard wished he had been born in an earlier day, when America’s west was still a frontier and its people pioneers. He proved that the same spirit, channelled into technology and business rather than land and conquest, could create and cross new frontiers.

Mr Packard and Mr Hewlett started HP in 1939 as a west coast firm in an industry dominated by east coast firms such as General Electric and Westinghouse. Their first sale was an audio oscillator used in a Disney film, “Fantasia”. HP built up ties with Stanford: an engineering professor named Fred Terman tutored many of those who would become Silicon Valley’s early stars. HP was one of the first firms to move into Stanford’s business park, ground zero of the Valley’s industrial explosion. It was an innovator and nimble in entering new business, traits that today define the region’s firms. And it made heaps of money: more than $30 billion in annual sales today, not terribly far behind IBM. It is the Valley’s largest company and biggest employer. Some 25 of the Valley’s top executives are HP alumni.

No doubt there would have been a computer industry in California without HP. It was just one of several electronics firms that were starting up on the west coast in the late 1930s, a trend that accelerated during the second world war. But HP is the only one from those early days to have survived as a force in the industry. The fact that HP started with two guys in a garage, and took off, was an inspiration. It wasn’t quite log cabin to White House – it was better.

But, the lack of courtesy apart, there is much that Mr Packard would have disapproved of in today’s Valley. Growing up in the depression, and seeing what banks could do to companies, he swore never to take on long-term debt. The firm grew on profits alone, and did not even go public until nearly its 20th year. Today’s computer industry start-ups often go public before they are two, and will beg

and borrow whatever it takes to keep up with the industry’s skyrocketing growth. Compaq reached $1 billion in annual sales in less than a decade, something it took HP 40 years to achieve.

The firm practises pragmatic benevolence. It has never had a lay-off, and was one of the first firms to offer share options and profit-related pay. It has trusted employees, leaving equipment rooms unlocked (and believing that access to equipment might encourage employees to tinker in their off hours, perhaps inventing some new product).

At 6ft 5in, Mr Packard had an imposing presence, and he relished face-to-face contact with his employees. When he worked at General Electric after leaving university, he spent a day on a factory line and cracked the problem behind its failure rate with vacuum tubes. From then on, when things went wrong at HP, he would head for the shop floor. This “management by walking around” (later dignified by management theorists as MBWA) reflected Mr Packard’s low tolerance for boardroom decision-making, business schools and professional managers (although the firm would have to embrace all three as it grew larger). In 1969 he was asked by theNixon administration to become assistant secretary of defence. He found the three years he spent in the job frustrating. The defence procurement system ran counter to the principles of efficiency HP held dear. He said the Pentagon would do as well picking names from a hat.

He was generous with his wealth. With his death the Packard Foundation’s endowment will grow to $6.6 billion, making it America’s third largest charity. He and Mr Hewlett gave Stanford more than $300m. Sharing his wealth with the region that made him great may partially account for his revered status with even the most jaundiced young Silicon Valley entrepreneurs. But there is more to it than that. The days of civility and organic growth may be gone in the industry hothouse, but the geeks still know solid technology, well made. David Packard set the tone of Silicon Valley by valuing nothing higher than a good machine. n