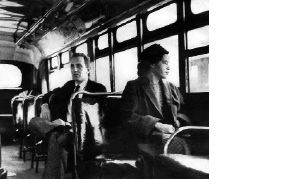

Rosa Parks

Rosa Parks, a pioneer of civil rights, died on October 24th 2005, aged 92

AS THE bus approached, she knew this particular driver was trouble. He had turned her off once before because, after paying her fare, she had refused to walk round the bus to get in by the back door. Rosa Parks knew better than to do that. While you walked round, the driver was quite capable of shutting the doors and driving off, leaving you stranded. So she had got in at the front and walked through to the back, like anybody else.

Or not quite like anybody else. In Montgomery, Alabama in the 1950s, as in much of the South, the first four rows of seats were for whites only. No more than four rows were needed, since few whites, and those poor ones, took the bus anyway. But whether they were filled or not, no black could sit there. Blacks sat at the back, in “Coloured”, where they belonged.

Between the two worlds was a middle section. Blacks could sit there, but if a white needed their seat they were expected to vacate not one seat, but the whole row, in order to spare the white the embarrassment of sitting by a nigger. On December 1st 1955, Mrs Parks sat in that section. After three stops, a white needed a seat. The three other blacks in the row stood up meekly, but when the driver ordered Mrs Parks out, she said, firmly, “No”.

In the mythology that came to gild this scene, Mrs Parks, who was 42, was said to have complained that her feet were tired. She herself denied it. Her job, as a seamstress in a department store, did not involve much standing. What had wearied her was drinking from black-only water-fountains, using black-only elevators, going to the back, standing aside, being demeaned in a hundred ways. She wanted no more of it. On December 5th, on the day she was convicted of violating a city ordinance and behaving in a disorderly manner, the young minister of the Dexter Street Baptist church in Montgomery, Martin Luther King, summed it up: “We are tired, tired of being segregated and humiliated, tired of being kicked about by the brutal feet of oppression.”

Mrs Parks had meant to do no more, she said, than show one rude bus-driver that blacks were being treated unfairly. She was not the first black ever to refuse to give up her seat. But her action had unprecedented consequences. King and other black leaders started a boycott of Montgomery’s buses; it lasted for 382 days, with blacks walking, cycling or going by mule instead. Other cities followed suit. Mrs Parks’s case went to the Supreme Court, which ruled that bus segregation was illegal. Most important, a movement of non-violent protest had begun, with King as its extraordinary spokesman, which eventually recruited the courts, the president and Congress to the cause of equal rights. And Mrs Parks, small, pretty, bespectacled and soft-spoken, was seen as its instigator.

Racism had tainted her life from the beginning. On her grandparents’ farm at Pine Level, in the Alabama wilds, she attended for a while a one-room school for blacks only; classes lasted only five months, to release the children for work in the fields. At night she sometimes heard lynchings, and the Klansmen riding. Once the body of a young black was found in the woods; no one knew who had killed him.

Her later schooling was cut short by the need to care for her sick grandmother. She took in sewing, learned typing, married young, but also got involved in black politics. In the Montgomery Voters’ League, she helped would-be voters weave their way through the Jim Crow tests designed to keep them from the ballot, and tried several times to register to vote herself. She also joined the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP), becoming secretary of the Montgomery chapter in 1943. Long preparation, therefore, preceded her act of defiance.Yet life in the South became too hard for her after the boycott. Fired from her job, she left for Detroit in 1957, the destination in those days of thousands of other poor blacks. She was still no celebrity, and continued to take in sewing. Eventually, a local black congressman, John Conyers, hired her to manage his office. She raised funds for the NAACP, appeared at events alongside King, and slowly came to realise that she was an inspiration. In 1999 she was given a Congressional Gold Medal of Honour, the highest honour possible for an American civilian.

As she grew older she was asked, often and almost obsessively, how much race relations had truly improved in America since the passing of the civil-rights laws. She thought there was still far to go. In 1994 she was beaten and robbed by a young black high on drugs and alcohol and fuelled, she supposed, by frustrations much like her own. Although he knew who she was, he said it made no difference to him.

In 1987 she had founded the Rosa and Raymond Parks Institute for Self-Development which, as one of its programmes, took children of different races round the country to learn about the civil-rights movement. They travelled by bus, naturally, sitting where they pleased. By this time, the famous green, white and yellow bus on which she herself had sat, unmoving, had become an exhibit at the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan. But Mrs Parks was well aware that the journey she had started that day was unfinished.