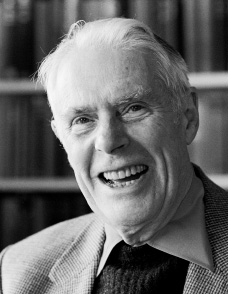

Anthony Powell

Anthony Dymoke Powell, English satirist, died on March 28th 2000, aged 94

When Anthony Powell was the literary editor of a magazine, he told his book reviewers to write concisely, “say what it’s about, what you think of it”, and perhaps make a joke. This admirable instruction naturally warms The Economist to Mr Powell, as it is not very different from that given to its own writers. He was also clearly his own man, undaunted by the corruption of friendship or popular taste. W. H. Auden, he said, was overrated, Graham Greene “absurdly overrated”, Laurie Lee “utterly unreadable”. Vladimir Nabokov writes “third-rate tinsel stuff’; Gabriel Garcia Marquez writes “pretentious middlebrow verbiage of the worst kind”. You might not agree with his judgments, but they were distinctive.

However, it is not as a literary critic that Mr Powell may be remembered. The yards and yards of obsequies that followed his death last week sought to honour him as one of the great novelists of the 20th century, a match for Marcel Proust. He certainly had admiration for Proust, who he considered not at all like those nonentities Greene and Nabokov. It is understandable to see similarities between “A Dance to the Music of Time”, Mr Powell’s sequence of 12 novels, and “Remembrance of Things Past”. Both are concerned with exotic upper middle-class behaviour, and both novelists wrote at great length, but that’s about all they have in common. One reason why Mr Powell’s admirers sought to place him among the elect may be that he had endured in the literary life more than any other writer. At Eton he was a fellow pupil with George Orwell. At Oxford he knew Evelyn Waugh. In Hollywood in the 1930s he had lunch with Scott Fitzgerald. And so on. He was still crafting words in his 90s, beginning, as he put it, with a paragraph of 30 words, turning them into 50, then 80, and revising all the time. Best to forget about Proust, and Dostoevsky, also sometimes linked to Anthony Powell, and appreciate him for what he was: a clever story-teller, with a quiet turn of wit.

In his writing style, Mr Powell was closer to Ernest Hemingway than Proust. A lot of his dialogue echoes Hemingway’s stripped-down mannerisms. Many Americans were among his fans. Just as they sought to master the language of the sea in the novels of Patrick O’Brian (Obituary, January 15th), so they patiently deciphered the fantastic world of Mr Powell’s England. (An American newspaper thoughtfully explained that he preferred to have his name pronounced to rhyme with Lowell.) Perhaps they took it seriously.

This was the England of which there will always be one: class obsessed, snobby but, in its way, endearing. In his personal life, Mr Powell encouraged this misleading view. He was married to an aristocrat and much concerned with genealogy. He claimed to have discovered a 12th-century ancestor called Rhys the Hoarse. In his memoirs he describes a life not far removed from the fantasies of his novels, peopled by friends called Fluff, Bumble, Hilly, Fram, Monkey, Liddie, Pansy and a dentist called Sussman, who is for ever fixing Mr Powell’s teeth. His father was a professional soldier, and when Mr Powell was called up in the second world war he naturally joined his father’s regiment. He was, of course, a Tory. He declined a knighthood, but was happy to be made a Companion of Honour, a rarer distinction.

Probably it is useful to be English to appreciate that much in Mr Powell’s writing is satire. But while the humour is a treat, it is the story that really matters. Anthony Powell was kind to his readers. In the 1m words or so in “A Dance to the Music of Time”, published between 1951 and 1975, several hundred characters make their distinctive entrances and exits. Some have walk-on parts, some disappear and then turn up surprisingly in later books in what he called “the inexorable law of coincidence”. A few dominate the action. Kenneth Widmerpool is present from his emergence in the first volume out of the mist on a school run to his bizarre death in the last volume. In between he serves a sinister capitalist, does well out of the war, marries a nymphomaniac and is made a lord. Widmerpool is always on the make, always pretending to be sympathetic to the latest political fad, the antithesis to the hopeless, if charming, losers of the upper class.

It is tempting to say that Anthony Powell despised the upper class. Perhaps he did, in the sense that in every satirist there is a bit of loathing. But he saw himself simply as an observer. His writing, he said, “dealt with things as they are”. Nick Jenkins, his narrator in “Dance”, seeks to be coldly objective. Although Mr Powell’s upbringing was on upper class lines, he never had the prospect of being one of the idle rich. For years he worked as a hack

in a publishing office. As a literary editor, he had “to read some frightfully boring book every fortnight”. In the early years his novels sold modestly. No wonder he was vitriolic about authors he considered had easy success. His urbane manner may have concealed an angry man. He grumbled about the “really terrible rubbish written about people”, including himself. He would have hated his obituaries, picking over his life. Even this kindly article? Probably.