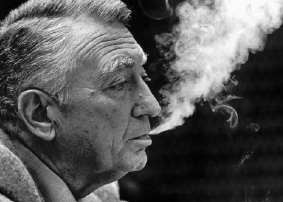

Leonard Tose

Leonard Tose, a big spender, died on April 15th 2003, aged 88

At a hearing by the United States Congress into gambling, the most compelling witness by far was Leonard Tose. He reckoned that he had lost about $40m through gambling, or it might have been as much as $50m. He couldn’t be sure. The money had seeped away gradually though consistently, sometimes no more than $10,000 during a frugal night at a casino, sometimes as much as $1m. But he had vast winnings too. He recalled times when everything went his way. The dollars rolled in obediently. He felt he could not lose. Such moments kept Mr Tose going when fortune seemed to have deserted him. In one bleak run of ill-fortune he lost 72 nights in a row. A lesser man would have given up. A lesser man would probably have managed to hold on to at least some of his money.

There was nothing stupid about Leonard Tose. In many ways his was the

classic American success story. His parents were immigrants from Russia who had settled in Philadelphia. Mr Tose told stories of his father selling goods from a pack on his back and saving up to buy a truck. From modest beginnings the son built up a business of 700 trucks whose logo became familiar throughout the United States.

The politicians who listened in fascination to Mr Tose’s account of how to lose money quickly were trying to understand the nature of gambling, and whether it should, or could, be controlled. Mr Tose was asked if he had any advice for Congress. “Don’t drink when you gamble,” he said. It sounded obvious, but it drew attention to the practice of some casinos that provide big-spenders with an unlimited supply of drink.

In various countries in the rich world similar inquiries are going on. In America and other liberal societies, a strongly-held view is that if you want to gamble, it is no business of the government. However, the consensus is that gambling is increasing, helped on by the internet, but little can be done about it except to provide counselling for those unkindly called “pathological” gamblers. The good news for governments is that gambling, though routinely deplored, is easily taxable, like its sinful sisters drinking and smoking. State lotteries are promoted as a good thing. Britain’s provides much of the money to nourish its much-praised culture.

One of the lures of gambling is its simplicity. The apparatus of a casino, the roulette wheels, the slot machines, requires little technological skill. Mr Tose favoured blackjack, similar to pontoon, a children’s game. The player has to be able to count up to 21 but it is otherwise undemanding. There are books that claim that a player with a prodigious memory for the sequence of cards can gain an advantage over the casino. But whether playing in Las Vegas or Atlantic City, Mr Tose never bothered with such affectations. What he liked was to play a number of games at once, often losing them all.

In a revealing moment he once said, “My hobby is spending money.” Gambling was not all of his life, and perhaps not the most important part of it. After Mr Tose had made his pile, he gave generously to medical charities. He willingly subsidised local public services that were short of cash. He provided playing fields for schools. He bought the Philadelphia police their bulletproof jackets. When the Philadelphia Eagles, a football team, was struggling to survive, he bought it for $16m. Sportsmen should stick together, Mr Tose said: as a student at Indiana’s Notre Dame University, he had played for its noted football team.

He was in the tradition of American industrialists who, having made a fortune,seek to give it away. The collections of European paintings and sculpture of Henry Frick, Andrew Mellon and other pioneering tycoons, bought when they became rich, were the foundations of America’s great national art galleries in New York and Washington. Leon Levy, an American financier who died on April 6th, aged 77, was a similar benefactor. He gave away $140m, including $20m to the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Mr Tose did not see himself as that sort of philanthropist, assembling alms for oblivion. If he had a philosophy it was to use his money to provide entertainment for the public. He liked the company of reporters, a habit he formed in the second world war when he edited an army newspaper. He became a regular read in American newspapers. One of the serial stories was about his five marriages and their consequences. One wife asked a court to declare him incompetent to handle money. She lost. He was sued by a casino for a debt of $1.23m, and claimed that it had made him drunk. He lost.

In the end he lost pretty near everything: his football team, the control of his trucking business, his Rolls-Royce, a model that matched that of his fourth wife. On his 81st birthday he was evicted from his colonial-style home, and he moved into a modest hotel, where the rent was paid for by some of his remaining friends. Last year, at the age of 87, he declined to be sorry for himself. He thought he had done well to reach a great age. He occasionally took a holiday, he said, but nothing flamboyant. He had a car, albeit one eight years old. And he still had his spirit.