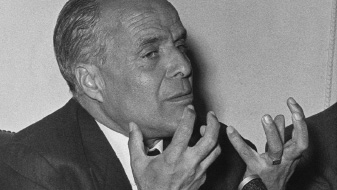

Habib Bourguiba

Habib Ben Ali Bourguiba, successor to Hannibal, died on April 6th 2000, aged 96

At his palace in Tunis Habib Bourguiba liked to show visitors portraits of four men from North Africa he most admired. They were Hannibal, perhaps the greatest of military commanders, St Augustine, who was born in what is now Algeria, Jugurtha, a king who stood up to the Romans, and Ibn Khaldun, who changed the way of writing history. Above these portraits was a larger one, of Mr Bourguiba. Modesty was never his problem. And, indeed, if you put aside the more absurd, and nasty, aspects of his life, there remained great accomplishments. He may not be remembered as a saint, or even as “the mighty warrior” described in the Tunisian constitution, but he did things that were, in their own way, remarkable.

Soon after he had won independence from France, he abolished polygamy, legalised abortion, allowed women to contract their own marriages, sue for divorce, and marry non-Muslims, a liberation of women that today remains unmatched in the Arab world. Within a decade of independence, two thirds of Tunisians were literate, up from a third in colonial times. He created a modern, largely secular state, which attracted investors.

Tunisia remained formally Islamic, but with much of the dogma dumped. Mr Bourguiba sought to end fasting during Ramadan. His ransacking of religious trusts had echoes of Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries. Tunisia was the only Arab state without a minister for Islamic affairs. He was anti-colonial, but, he insisted, not anti-western; time has made his foreign policies look visionary. He advocated recognition of Israel at a time when most Arab nations still sought its extinction. Tunisia boycotted the Arab League. Yet, seemingly charitably, he gave Yasser Arafat and his Palestinians sanctuary when they were driven from Lebanon in 1982 and looked a spent force.

Habib Bourguiba was a French-trained lawyer. Back in the 1930s he first became prominent in independence politics. The French knew a troublemaker when they saw one and Mr Bourguiba spent some 12 years in French jails, in the Sahara and on the Brittany island of Groix. Nevertheless, he said he admired the French, even while fighting them. During the second world war, when most Tunisian nationalists supported the German−Italian axis, Mr Bourguiba declined to reject the French, even when in 1942 the Germans let him out of his French prison. By then America had entered the war and the Germans were faltering in Russia. It looked likely that the French would be the future negotiators.

In 1956 Tunisia was granted independence, with the Bey of Tunis as head of state and Mr Bourguiba as his prime minister. But Mr Bourguiba, who styled himself as the first independent leader of his country since Hannibal, was disinclined to share power. One year after independence he abolished the monarchy and became president. His Tunisia was a one-party state. Opponents were cruelly swept aside. Rival independence leaders were either hounded into exile or humiliated in show trials. Mr Bourguiba spat in public at ministers he sought to discipline. In 1961, Tunisian agents

murdered a former comrade of Mr Bourguiba, Salah Ben Youssef, in Frankfurt.

Statues began popping up. His birthday, August 3rd, became Tunisia’s national day. Streets were named after him. He had a mausoleum built of white marble and decorated with gold leaf. In 1975 he had parliament declare him president for life. Some people thought he was losing his mind. Tunisians were astonished when he said on television that he had only one testicle.

This fascinating disclosure was naturally much discussed by Tunisians. The mighty warrior had one son, by his first wife, Mathilde Lorrain, but other women were also important in his life. In 1961 he divorced Mathilde, after she had imbued him with her ideas of equality for women, apparently because Tunisians considered that a true patriot would not have a French spouse. His second wife, Wassila Ben Ammar, became a power behind the throne. Officials said she bugged cabinet meetings, and decided who should be a minister. For the first time in the Arab world, a photo of the first lady began to appear alongside that of her husband. Mr Bourguiba divorced her in 1986, and he was looked after by his niece, Saida Sassi.But by then Tunis’s Camelot was unravelling. The judiciary, the press, the trade unions, which had all tasted freedom in the early years of the republic, had been shackled. Bread-riots were becoming frequent. Crushing Islamists was becoming an obsession. Mr Bourguiba was demanding mass executions after bombings in the tourist resorts of Sousse and Monastir.

In the end, Mr Bourguiba was better treated than he had treated his rivals. The coup was medical: on November 6th 1987, the prime minister, Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali, gathered a council of seven doctors who pronounced Mr Bourguiba senile and incompetent. For the next 13 years until his death he was under house arrest, his visitors mainly restricted to relations. If he sought a change of scenery he could visit his mausoleum, with the words engraved on the door, “Liberator of women, builder of modern Tunisia”.