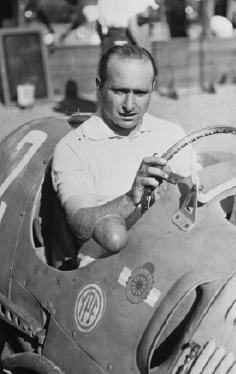

Juan Fangio

Juan Manuel Fangio, racing driver, five times grand prix world champion, died on July 16th 1995, at the age of 84

One day Juan Fangio’s record of being five times the world champion racing driver may be beaten. But even if that happens many people will continue to regard him as the greatest grand prix driver of any generation. Better than the gifted Ayrton Senna, three times the world champion, who was killed in 1994? Better than Stirling Moss, who twice outraced Mr Fangio? Or was there something special about motor racing in the 1950s, when Mr Fangio gained his fame, that stays in the memory and adds to his lustre?

Nostalgia plays a strong part in distorting assessments of sporting heroes. That is also true of another sportsman, Harold Larwood, an English cricketer, who died on July 22nd at the age of 90. He was the most feared – and controversial – fast bowler of his time. He aimed at the batsman’s body in order to induce a catch. In 1926 the England team, with Mr Larwood its hero, beat the Australians, who were left whimpering that this was not cricket. This is a happy memory, especially these days when England mostly loses. People may argue about whether Mr Larwood was as great a bowler as, say, some of the recent West Indians, but the nostalgia for old cricket, before sponsorship, before body armour, will only grow with the story-telling.

The same sentiment may be felt for Mr Fangio. The drivers in his day were plainly visible to the crowd, riding their mounts like cavalry, their arms bare to the wind, their goggles streaked with oil if something had gone wrong, as often it did. The cars of Mr Fangio’s time were not really made to go as fast as they were driven. Once, Mr Fangio’s seat came adrift when the securing bolts broke. Somehow he clung to the cockpit with his knees.

If a car crashed it would probably explode. At least 30 top drivers were killed between 1951, when Mr Fangio first became world champion, and 1958, when he retired having driven the cars of four great marques, Alfa Romeo, Maserati, Mercedes-Benz and Ferrari. Motor racing sometimes seemed like a Roman blood sport, with Juan Fangio as a surviving gladiator, saluted by the chequered flag, a cigarette dangling from his mouth, acknowledging the cheers with a casual wave. In those days no one squirted champagne. It would have been considered vulgar.

Mr Fangio took care to cultivate a non-vulgar style. When taking a corner, most drivers would not be too bothered if they shaved the straw bales put there to protect the crowd. Mr Fangio would elegantly just miss them. Neither did he care for speed for its own sake. If he was going to win anyway he was content to cruise home. “A car is like a creature that lives, with its own emotions and its own heart,” he said. “You have to understand it and to live with it accordingly.” Such “understanding” seemed to enable Mr Fangio to cajole an extraordinary performance from his car when the need arose. One of his tricks was the “four-wheel drift”, a controlled skid for taking corners at high speed. It was used with effect in 1957, at the German grand prix at the Nurburgring, 500km (313 miles) round and round the Eifel mountains, with numerous bends. He started with a light load of fuel, reckoning that he would build up enough lead to refuel comfortably

during the race. But the refuelling was bungled. His lead of 28 seconds became a deficit of 51 seconds. In what was probably Mr Fangio’s finest race, he pushed on ferociously, passing the leaders with one lap to go.

Stirling Moss said Mr Fangio was a gentleman “not of birth, but of being”. He was an Argentine, born the fourth of six children in a family of Italian immigrants. At 13 he was a car mechanic. In his 20s he was winning long distance races, including one from Buenos Aires to Lima and back, about 6,000 miles. Stamina was one of hismany admired qualities, although he got tired like anyone else. Chewing coca leaves kept him awake. Later, in Europe, he used pep pills.

The Argentines acknowledged his growing fame by naming a new dance the “Fangio Tango”. He received the blessing of Juan Peron, then the dictator of Argentina. Publicists in the racing world sought to link him with pretty women. Gina Lollobrigida was one. But Mr Fangio was not one of the sports world’s lechers. For years he was greeted at the end of a race by a matronly woman who was assumed to be his wife. But she wasn’t. Their friendship apparently ended and Mr Fangio never married.

Rather than being a heart-throb Juan Fangio might be considered an inspiration to the elderly. He would have been happy with that encomium. At the time of his greatest successes he was in his 40s, a pensioner in motor-sport terms. Later, he attributed his great age to living simply – plenty of sleep, healthy food, and a special Fangio tip: don’t go faster than you have to.