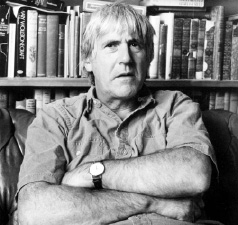

Paul Foot

Paul Foot, a British investigative journalist, died on July 18th 2004, aged 66

“THERE are more people walking the streets of Britain who have been freed from prison by Paul Foot than by any other person.” Mr Foot was far from being vain or self-seeking, but he must have been pleased by this compliment from one of his editors at the Daily Mirror. It was a vindication of his work as a campaigning journalist whose efforts on behalf of victims of injustice were not only tireless and brave, but also capable of bringing about results that would change people’s lives. Though he wrote articles of every kind, and books too, his innovation was the investigative column, a device that worked because it was based on hard research rather than mere prejudice and polemic.

Not that he was short of prejudice and polemic. Far from it: they were the starting-point of all his inquiries, for Mr Foot was a committed socialist of a largely unreconstructed kind, with a particular admiration for Leon Trotsky. Indeed, many of his energies were devoted to the cause of the Socialist Workers Party, a Trotskyite outfit. How could anyone with views such as his produce balanced journalism? Mr Foot could not. He did not even try. But that was not the point. He still could, and did, produce excellent work. Doggedly – the word aptly describes the terrier in him – he dug out information that powerful people did not want to see published.

The tradition of radical journalism goes back a long way in Britain, to William Hazlitt, William Cobbett, Tom Paine, John Wilkes and beyond. These 18th- and 19th-century essayists and pamphleteers were not self-described neutral observers who meticulously separated facts from opinions, discarded the opinions and then left readers to form their own judgments. They were committed campaigners who had a point of view and made no apologies for expressing it. Mr Foot was in that tradition.

He was also in the tradition of British satire, whose most notable exponents have usually been writers, such as Jonathan Swift, or caricaturists, such as James Gillray and Thomas Rowlandson. In the 1960s, the genre enjoyed a wonderful renaissance, bursting out on every front – the stage (“Beyond the Fringe”), night clubs (The Establishment, in London), television (“That Was The Week That Was”) and, most enduringly, the magazine Private Eye.

By circumstance and breeding, Mr Foot slipped easily into this world of satire and dissent. His grandfather, Isaac Foot, a devout Methodist, had been a Liberal MP, as was his uncle Dingle, though he later defected to Labour. Another uncle, John, became a Liberal peer, and a third, Michael, was to lead the Labour Party. His father, Hugh (later Lord Caradon), was a diplomat and colonial servant whose career included terms as governor of Cyprus and Britain’s ambassador to the United Nations.

The taste for satire started at Shrewsbury School, where he wrote for the school newspaper, as did his near contemporaries, Christopher Booker, Richard Ingrams and Willie Rushton. This trio went on to found Private Eye in 1961, which Mr Foot was to join six years later. Though he wrote for many other publications over the years – the Daily Record in Glasgow, the Daily Mirror, the Guardian among them – and edited the

magazine Isis while up at Oxford in 1961 and later Socialist Worker, he never cut his links with the Eye.

Yet Mr Foot was unlike the others on Private Eye. For most of them, such as John Wells, an Oxford friend, the main aim was to puncture pomposity and make people laugh. Mr Foot had a sense of humour and could be a devastating exponent of mockery, but he was above all a polemicist and muck-raker. His contributions to the Eye were not cartoons like Rushton’s or spoof diaries like Wells’s; they were the scandalous revelations in his “Footnotes” column.

These, too, were different from the classical writings of British radical journalists, and they – and Mr Foot’s other investigative books and articles – were his real contribution to public affairs. To most people his politics seemed potty. His revelatory journalism was different. Though equal scepticism greeted his first inquiries into potential scandals, his diligence and persistence nearly always won him admiration in the end. Those who fell foul of him included politicians(Jonathan Aitken, Jeffrey Archer, Reginald Maudling), union leaders (Clive Jenkins), architects (John Poulson), journalists (notably his boss at the Mirror, David Montgomery), businessmen (the list is long), as well as disc jockeys, civil servants and countless others. His exertions to right injustice were equally impressive: the Birmingham Six, the Bridgewater Four and the Cardiff Three were all freed from prison after campaigns led by Mr Foot.

On two occasions, Mr Foot stood for public office. The first time, in 1977, when he tried for Parliament, he gathered only 377 votes. He did better in 2002, as candidate for mayor of Hackney, in east London, but still came third. Clearly, his heart was not in it on either occasion. He wrote, after all, that “responsible office in capitalist society ... leads inevitably to arbitrary and demeaning behaviour towards others.” Perhaps he really agreed with one of his heroes, Percy Bysshe Shelley, that “Poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world.” So far as is known, Mr Foot did not unearth a scandal involving poetry.