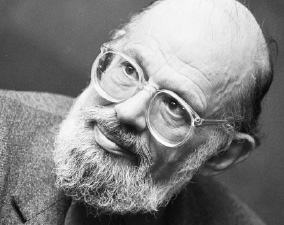

Allen Ginsberg

Allen Ginsberg, who howled about life in America, died on April 5th 1997, aged 70

When Allen Ginsberg was being shown around an Oxford college he asked to see the rooms Shelley had used. His companion was uncertain of their whereabouts, but pointed hopefully to a door. Mr Ginsberg entered, dropped to his knees and kissed the carpet, much to the surprise of the occupant, who was making tea. Shelley would have been amused. He would have recognised a fellow romantic and quite likely invited him along to meet Keats and Byron. And as a connoisseur of dope, the American must have a chat with De Quincey about the virtues of opium.

The curious era in American culture that produced the beat generation (from beatitude or deadbeat: take your pick) was in some ways a reliving of England’s 19th-century romantic movement. The beats rejected the rationality of normal living. In their pursuit of “flower power” some sought a return to nature. Mr Ginsberg was their outrageous Byron, although far from handsome and in love with men rather than women.

“Coming out”, green politics, feminism, trash fashion and much else that today hardly raises an eyebrow, made its bow in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Mr Ginsberg and his friends, among them Jack Kerouac and William Burroughs, would not claim to have begotten all these innovations, but they were a catalyst. Although the Eisenhower presidency (1953−61) is thought of as a stodgy period, the civil rights movement was growing and in 1961 America sent its first soldiers to Vietnam. Civil rights and draft dodging were oxygen to the beats.

Allen Ginsberg, though, grew up in a nine-to-five world. His parents were Jewish immigrants from Russia determined to make good. His father was a teacher, and wrote poetry of a traditionalist style. Young Allen went to university and was expected to become a lawyer. This ordered life came apart. His mother, who for years had had bouts of schizophrenia, was confined to a mental home. Mr Ginsberg dropped out and had a series of jobs, including a spell writing copy for advertisements. He settled in San Francisco because of its “tradition of Bohemia” and wrote “Howl”, the poem that made him famous.

Just as an earlier generation first heard of Ulysses when it was banned, “Howl” became famous by being prosecuted for obscenity. In the course of a long and widely-publicised trial its opening lines were read by millions who would not normally pick up a book of poetry. Unlike Ulysses, with James Joyce’s peculiar syntax, “Howl”, whatever its merits as poetry, is a pretty straightforward read: “I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked, / dragging themselves through the negro streets at dawn looking for an angry fix.”

Even better for a public avid for novelty, Allen Ginsberg turned out to be a character, a bald-headed bearded lump in sandals, never short of a lively opinion and, if there was a photographer around, happy to play the buffoon. He travelled across America reading his poems to large, mainly young audiences who seemed not to mind that he was often incomprehensible, perhaps because his admirers were themselves blotto on drugs.

Even during his travels abroad he was often in the headlines. He was expelled from Cuba and Czechoslovakia for advocating homosexuality, and from India, where he sought “eastern mysticism” and was accused of being an American spy, and from various countries in Latin America where he said he was looking for new drugs. At a party in London he took off his clothes and hung a hotel notice, “Do not disturb”, on his penis. “Poetry is best read naked,” he said. John Lennon, not a man usually offended, shielded his wife and walked out in disgust. Back home, Mr Ginsberg practised yoga and other forms of meditation, declaring them to be superior to drugs, and became a devotee of a guru who dressed his staff as English butlers. He once bemused police at a civil rights demo in Chicago by chanting the mantra “om” for seven hours.

The New Yorker published a sly version of “Howl”: “I saw the best minds of my generation / Reading their poems to Vassar girls / Being interviewed by Mademoiselle / Having their publicity handled by professionals.”Nevertheless, Allen Ginsberg was said to be a generous man, giving support to less famous poets and other writers. He pioneered poetry designed to be read aloud. He turned down offers from big publishing houses and stuck with the small firm that first put him in print. He produced a mountain of work published in some 40 books. On one day just before he died he was said to have written a dozen poems.

Will his poetry endure? Some of his poems are now in anthologies. “Kaddish”, about his mother’s death, is well regarded. But while every poet may hope to outlive fashion and be read for ever, there are not many Shelleys. The judge who heard the “Howl” case decided that the poem had “social importance”. That, anyway, was true enough.