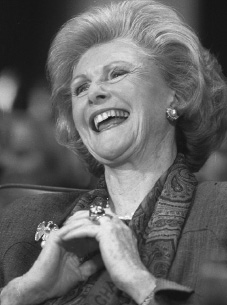

Pamela Harriman

Pamela Digby Churchill Harriman, ambassador and courtesan, died on February 5th 1997, aged 76

If you collected a dozen or so of Pamela Harriman’s fancier lovers and put them round a dinner table, you had the makings of a world government. Not in the sense of cabinet ministers and presidents – that would have been far too crude and plodding for the stylish Mrs Harriman – but in the sense that her galaxy of fellows and husbands could, together, have bought much of the world and made it spin.

Imagine the dinner party. Her first husband, the drunken Randolph Churchill, might have brought along his father, Winston. There could have been a general or two, from either side of the Atlantic, whom Mrs Harriman helped win the second world war. The airwaves would have been vibrant enough: Bill Paley of cbs owned a lot of them; Ed Murrow, America’s greatest wartime correspondent, was their master. Fine wine at dinner? Elie de Rothschild, owner – among other things – of Château Lafite, would see to that. Nice pictures on the wall? Even without her Murillos and Renoirs, Carter Brown, director of Washington’s National Gallery, could help out.

Want to go racing tomorrow? Aly Khan, the Aga’s heir, would give you a tip. Something soapy after dinner? Step forward Frank Sinatra. Or something still more soothing? Then why not a late-night viewing of The Sound of Music, courtesy of husband number two, Leland Hayward, who produced it (and left the royalties, trickling in every year, to darling Pamela). If you wanted to leave in a hurry, Gianni Agnelli, who owned Fiat, could provide fast wheels. A more sedate exit? How about one of Stavros Niarchos’s yachts? Mrs Harriman’s life was an astonishing tale of sex, money and – far sweeter smelling than both those coarse commodities – power.

But it was not how she started. Her father, the 11th Baron Digby, was charming and gentle, knowledgeable about pigs and other rural matters. She was red-headed, bouncy more than pretty, always a bit pushy, and slightly unpopular with her crowd. But when she was 19 she met and very quickly – and disastrously – married the only son of the man shortly to be prime minister. When he was away at war, she took up with the rich and famous and glamorous – and never looked back. She rapidly divorced, then played the field for 14 years. Her second marriage, to Hayward, lasted from 1960 until he died, in 1971. Soon after, she married a mega-rich former lover, Averell Harriman, and became an American. Harriman was once governor of New York, ex-ambassador to the Soviet Union and Britain, and one of the Democratic Party’s biggest benefactors. When he died in 1986, leaving her assets worth over $100m, her storm-tossed ship had finally come home.

She became, in her own right, the doyenne of Washington hostesses, giving power-meals largely in the cause bequeathed to her by Harriman: the resurrection of the Democratic Party. She helped promising lads from Hicksville – like a certain Bill Clinton. They were grateful. He gave her a lovely embassy in Paris. At last she was both rich and powerful in her own right. She had won.

Why did she do it? How did she manage it? And did it, in the end, make her happy? From an early age, despite – perhaps because of – her rather dozy background, she was driven to succeed. Perhaps her unpopularity in early life egged her on – to “show those bitches” who was best. She liked glamour. She adored money – not so much for hedonistic reasons as for the sense of security she hoped it would bring. Power, perhaps, became an additional aphrodisiac. Having the ears of presidents and prime ministers as well as tycoons and film stars was marvellously satisfying.

How did she do it? She was tough and manipulative, though not especially subtle. She was not very clever, certainly not bookish. She had little interest in ideology – if Harriman or Clinton had been Republicans, she wouldn’t have minded a jot. Although not a great beauty, she kept a trim figure. Doubtless she was expert between the sheets. The key to her success, though, was her ability to fix her concentration on one man – one at a time; and convince him that she was utterly enthralled. It is a recipe that few could resist. After Harriman died, the prospect of her financial backing was an additional allure. She was loyal to most of her friends. A deal with Pamela, it was said, was a deal. She was good to her two later husbands when they were dying.

Was she happy, though? She sparkled. But, at the end of the day, despite all those luxuries, it was a harsh life. Old British friends, especially, mocked her transparent ambition (which Americans took more at face value). Lovers she hoped to marry dumped her. Her husbands were difficult.

Her stepchildren liked her. Even the goal of financial security eluded her in the end as relations clawed back much of Harriman’s estate.

Was there not always, at the very back of her mind, just a nagging feeling that she was being laughed at, even scorned? Her façade was shiny. It is not certain that, as the French say, she really felt bien dans sa peau.