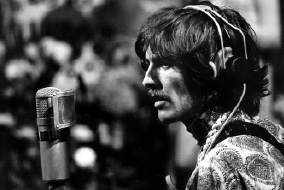

George Harrison

George Harrison, a Beatle, died on November 29th 2001, aged 58

So much has been written and broadcast about the death of George Harrison that it might be thought that there was nothing left to say. But to hazard such a rash prediction would be to underestimate the resourcefulness of what might be called the Beatles generation, now steeped in melancholy. This may prove to be a long goodbye. The large sections of newspapers that have been devoted to Mr Harrison’s career could be merely the opening bars of a requiem. Already there is talk of biographies and memorial record albums, along with television and radio retrospectives and perhaps a film.

Those who were not even born in the 1960s, when the Beatles were at their most active, may have been surprised that, to take a random example, the Daily Telegraph, a London newspaper that prides itself on the quality of its readership, should have cleared its front page of other news to report Mr Harrison’s death, continuing the saga inside for five more pages. Other British newspapers were equally proliferative. American and European newspapers were more restrained, but generous in their treatment of the famous Brit. Not since the death of Princess Diana, and before that of Churchill, had there been so many tears in print.

Still, the young are mostly tolerant of the eccentricities of the middle-aged. Those who had once courted and cuddled to the music of the Beatles and now ran the media were entitled to their harmless indulgence. The death of Mr Harrison seemed also the death of their era. When it was proposed that a minute’s silence should be observed no one objected, even though such an obsequy is normally reserved for the war dead. After all, it wasn’t often that an era died.

It may seem odd that the same vast coverage was not given to the death in 1980 of John Lennon, the founder Beatle. But Lennon was shot dead. The reporting was extensive, but hurriedly put together. George Harrison had been ill for a long time. By the time he died the essays on his life by his admirers had been written and polished. Mostly they were moving, although perhaps avoiding Voltaire’s dictum that “to the dead we owe only truth”.

The story of George Harrison’s life can be simply told. He was a busman’s son who left school at 14 and worked briefly as an electrician’s mate. He won a place in John Lennon’s little group in Liverpool because he played the guitar a bit better than either Lennon or Paul McCartney. He has been called the “quiet Beatle”; perhaps shy is a more accurate adjective. He found it difficult to cope with the publicity that underpinned the Beatles’ success, and for a dark period in his life was addicted to drugs. Like the other Beatles he made huge amounts of money. He bought a house with 120 rooms, and shut himself away from the screaming fans saying, “I would never want that again.” The British film industry was grateful to him for backing several productions during one of its customary hard-up periods, among them “Monty Python’s Life of Brian”. He was married twice. Of Mr Harrison’s songs perhaps “Something” is the best known.

Frank Sinatra thought it great.

A mixed life, but a better one perhaps than mending fuses. He had luck, just as the Beatles had luck. Their luck started when they were taken over by Brian Epstein, who ran a record shop in Liverpool near the Cavern Club, where the Beatles were regularly performing. The role of Epstein has tended to be minimised in the golden memory of the Beatles, perhaps because he was thought to be too fond of young men. But Epstein was the one who groomed the Beatles to look cuddly rather than rough, to brush their hair and to wear neat suits rather than leather.

In 1962, after two years spent hawking their demo tapes around reluctant record companies who said that guitar groups were finished, he got the Beatles their first big deal. Epstein said he would make them “bigger than Elvis”, and so he did. By the mid-1960s they were the most important pop group in Europe and the United States. Any Beatles memorabilia from that time tends to become a museum piece. A few days before Mr Harrison died his first guitar, bought for pennies, drew a bid at an auction in London of £25,000 ($35,500). After Epstein died in 1967 the group began to break up with its membersgoing their own way, sometimes as soloists, sometimes forming new groups, sometimes doing not much. George Harrison for one said he was tired of going “round and round the world singing the same ten dopey tunes”.

A talent for publicity cannot in itself explain why they did so well. And musically they have probably been overpraised. Epstein managed other groups, among them Gerry and the Pacemakers, but although successful they never matched the appeal of the Beatles. Nor did the Rolling Stones with their pastiche of American blues, although some preferred their fiercer music. To use an expression that flourished in the 1960s, it seems that the Beatles more than other groups caught the Zeitgeist, the spirit of the age. “All You Need Is Love”, declaimed against a pounding background of cellos, could be hypnotically compelling, although hardly a message of Voltairian truth.