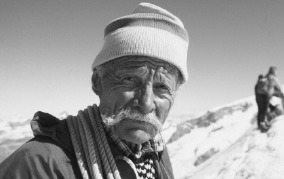

Ulrich Inderbinen

Ulrich Inderbinen, the world’s oldest mountain guide, died on June 14th 2004, aged 103

THE Matterhorn in Switzerland, with its bent, jagged peak and steep glacial ridges, is frequently climbed these days. As on many popular yet difficult mountains, ropes and ladders are fixed permanently into the rock and ice, and huts line the route to the summit. But the Matterhorn has long had a reputation for deadliness – half the members of the first group to climb it, in 1865, perished on the descent – and it remains one of the world’s most dangerous peaks. Crowds make it more so, as novice climbers are tempted by its fame.

This awesome mountain was a hugely important place in Ulrich Inderbinen’s life. He was born in 1900 in Zermatt, at the mountain’s foot: a remote village of only 750 people, with tourism a small but burgeoning industry. Mr Inderbinen rarely left the region of his birth, and was 20 before he took the train to the nearest town. To make up for it, he climbed out of the valley quite often – almost daily for nearly 70 years. He scaled all 14,700 feet of the Matterhorn more than 370 times, though he is said to have lost track of the exact number.

Mr Inderbinen thought the Matterhorn “the most beautiful mountain in the world”. Although it was only one of many mountains he climbed over the course of the 20th century, guiding innumerable clients up and down with inexhaustible good cheer, no other so engrossed him. On his first ascent, at the age of 20, he went with his sister Martha and a friend of hers. The girls wore long skirts and their ordinary shoes, and the lanterns they were carrying kept blowing out. Since none of them knew the route, they followed scratch-marks made by previous climbers on the rocks. On his last ascent, bent double under his ropes at the age of almost 90, he conquered the mountain in four hours.

Mr Inderbinen met life with the same equanimity as the mountains, his dry wit punctuating his monumental energy. When asked if he ever got bored, climbing the same peaks again and again, he replied, “Only when the clients walk too slowly.” When one journalist pointed out an enthusiastic review from an American client in the 1930s, Mr Inderbinen replied: “Perhaps he did not know any other guides.”

But rivalry was by no means absent from Mr Inderbinen’s life. As a young guide, he would walk for four hours each morning to catch visitors disembarking from the train above Zermatt. He took up ski-racing at 82 when he realised that, with no other competitors in his age-group, he could win every race – which he did. Until almost the end of the century he continued to take climbers up easier local peaks, proving to other guides how sure he still was. For his 95th birthday he was given an ice-axe as a present, which he put to good use. One of Mr Inderbinen’s few regrets was his family’s veto of an attempt to climb Mount Kilimanjaro, the tallest mountain in Africa, when he was 92.

Mr Inderbinen might have been a farmer like his parents. Much of his early life was spent herding cows and picking edelweiss for tourists. He did not get his first skis, made from local larch, until he was 20. But he eventually chose mountain-guiding in emulation of his uncle Moritz, a famous guide when Mr Inderbinen was a child.

At first, business was slow. Between customers, Mr Inderbinen had to cut trees and shovel snow. Then came the second world war, with no visitors at all. For a while Mr Inderbinen served in the ski patrol of the Swiss army. He would glide in the mountains above Zermatt, often alone and often at night, forbidden even to switch on a torch. Whether or not he truly helped the war effort, it was a billet that suited him exactly.

His chosen profession allowed for a bit more camaraderie in peacetime.Indeed, the profession of a guide entailed a paradoxical combination of solitude amongst the high glaciers and sociability among his fellow mountaineers. And once visitors poured back to Zermatt, he began to be in demand. Unusually in the climbing business, he sought fame through service – guiding others safely up mountains, rather than conquering them for himself.

Mr Inderbinen’s life was notably harmonious. He had no car, telephone or even bicycle, and chopped his own firewood deep into old age. He made his living on his feet or his skis, proceeding steadily; he did not believe, he said, in doing anything hastily, on the slopes or elsewhere. (This, however, was not always true; he gave up mountain-guiding, at 97, when he realised he had taken ten minutes longer than he should have done to decend the Breithorn.) He built his house with his own hands, finishing it in 1935, and lived in it for the rest of his life. He knew what he wanted, and had it close by. Especially, he wanted those particular mountains.

George Mallory, a British mountaineer who tried to conquer Everest and died on it, famously said he wanted to climb the peak “because it is there”. Mallory crystallised a romantic vision of the mountaineer, chasing after dreams on ice-wrapped summits far from home and hearth. Ulrich Inderbinen could not have been more different. He went up mountains not because they were there, but because he was. He died gently, in his bed. And though he may not have been the first to climb the Matterhorn, he seems to have climbed it best.