Christiaan Barnard

Christiaan Barnard, heart surgeon and celebrity, died on September 2nd 2001, aged 78

It was a decent enough lifespan, 78 years, but Christiaan Barnard had, it seems, planned to live much longer. In his search for an elixir he injected himself with cells taken from the fetuses of animals. “It’s worth a try,” he said. Ageing, he maintained, was abnormal. He was involved with a clinic in Austria that offered “rejuvenation therapy”. He endorsed a skin cream that contained an ingredient said to have prolonged the lives of fruit flies but which was withdrawn from sale after customers complained that it was not working for them.

At Dr Barnard’s lectures, for which he charged up to $10,000 a time, his listeners would sometimes become a little impatient when he dwelt at length on his experiences as a heart surgeon; they were keen to know what progress he was making on longevity. Heart transplants are no one’s idea of fun, but most people are interested in a few tips about how to put off the trip to heaven.

Relax, take a holiday, put away your mobile phone, drink red wine. But that was not all, said the doctor, in case his listeners felt they were not getting their money’s worth. Sex, he said, was the magic ingredient, preferably with romance, “the most beautiful, healthiest and most pleasurable way” to keep fit. It cheered up the audience, even though the advice was not new. Dr Barnard had practised romantic sex ever since he had become famous after performing the world’s first human heart transplant in 1967.

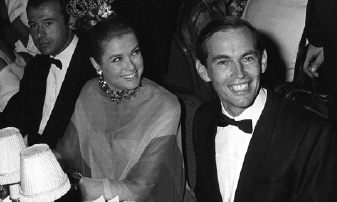

To the delight of newspapers, especially in America and Europe, the wonder surgeon was wonderfully photogenic, and had kept his boyish good looks into his 40s. He had a good line in chat too and seemed to love publicity. In the entertainment business women especially, Sophia Loren, Gina Lollabrigida and others, recognised a soulmate. Paris Match said he was one of the world’s great lovers. Our picture is of him with Grace Kelly in 1968. At the age of 42 he dumped his wife of 22 years and married a teenager. He was married once more. He had six children. “I have a woman in my life at all times,” he said. But although immortality by way of sex eluded Dr Barnard, there were compensations. As a heart surgeon he did memorable work, although even here there are reservations to be made.

Christiaan Barnard learnt about heart surgery in the United States, chiefly at the University of Minnesota, after working for ten years mainly in general practice in his native South Africa. Whatever ambitions American surgeons may have had to replace a failing heart with a healthy one, the medical ethics prevailing at the time were against using the heart of someone who was brain dead while the heart was still functioning, albeit artificially. Back in South Africa Dr Barnard joined the heart department of Groote Schuur Hospital in Cape Town and eventually headed a team of 30. “We didn’t have the legal restraints that existed in the United States,” he recalled. In 1967, after nine years of experiments, mainly on dogs, Dr Barnard and his team removed the heart from a young woman brain dead after a car accident and used it to replace the wonky heart of a 55-year-old grocer. The substitute heart started to beat vigorously and the

operation was deemed a success. The patient died 18 days later of pneumonia. Large doses of drugs designed to prevent the heart being rejected had left him open to infection. Dr Barnard’s second transplant patient lived for 18 months after the operation. His longest-surviving patient lived with a substituted heart for 23 years.

Dr Barnard carried out 75 transplants before giving up surgery in the 1980s because of arthritis. An estimated 100,000 heart transplant operations have so far been carried out in various countries. In the United States it is claimed that 75% of patients can expect to live for at least five years after the operation. What Dr Barnard did was to show the way. Other heart surgeons, suppressing their irritation about his love of fame, have been generous in their praise for his courage in confronting the question of brain death. Today it is accepted in many countries that brain dead means dead, although in Japan there were no heart transplant operations for 31 years after a surgeon who carried out the operation in 1968 was accused of murder. Many Japanese take the view that a person is alive while the heart is beating, and the country’s law on the subject of brain deathremains cloudy.

Dr Barnard dismissed what he called the mystique of the heart. The object of desire in poetry since humans acquired words was simply a primitive pump. One of the doctor’s charms was his simple directness, perhaps acquired from his father, a missionary who drew big crowds as a preacher. Dr Barnard’s openness amused the glamorous, but it also made him respected in his own world in racial South Africa, where he had to make choices. They tended to be good ones. He campaigned for black doctors to have equal pay with whites. He employed non-white nurses to treat white patients. He operated on blacks and whites according to their needs. An American he operated on said he hoped he had been given a white heart. Dr Barnard said he could not say. You couldn’t tell the difference.